The Normal Lymph Node

Anatomy

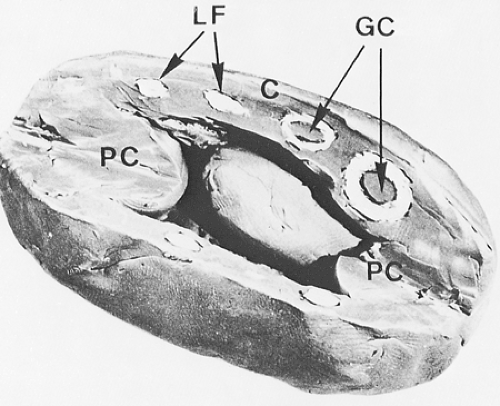

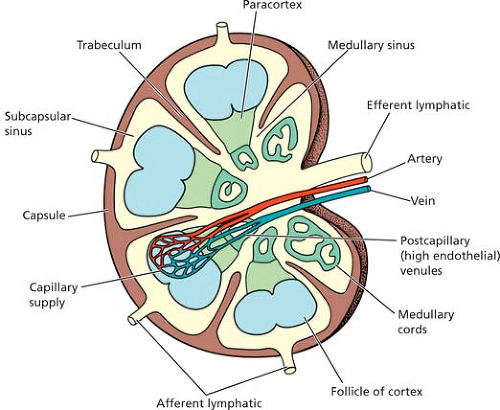

In the lymphatic pathway, lymph nodes are peripheral lymphoid organs connected to the circulation by afferent and efferent lymphatics (Fig. 1.1). These ovoid, round, or bean-shaped nodular formations, composed of dense accumulations of lymphoid tissue, vary in size from 2 to 20 mm and average 15 mm in longitudinal diameter (1,2) (Fig. 1.2). Normally, lymph nodes are not palpable. They become detectable as a result of intense immune reactions or tumor metastasis. The cut surface is gray-pink, soft, and homogeneous. A diameter larger than 3 cm, a firm consistency, and a white and nodular cut surface are features suggestive of neoplasia. The characteristics of each group of lymph nodes vary in relation to age and site in the body; for example, mesenteric nodes have wider medullary cords and sinuses, whereas peripheral nodes, particularly those draining areas of active antigenic stimulation, such as the neck and abdomen, have larger and more numerous germinal centers. Peripheral nodes are also more numerous in younger than in older persons and are absent in newborns (3).

Functions

The major functions of lymph nodes are lymphopoiesis, filtration of lymph, and processing of antigens. The immune response takes place in an integrated lymphoid system that includes the lymph nodes, spleen, and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissues (MALT). All lymphoid cells originate in the bone marrow; B cells mature in the bone marrow, whereas T cells migrate to the thymus, where they undergo further differentiation. From these primary lymphoid organs, B and T cells colonize the secondary lymphoid organs: the lymph nodes, where they respond to antigens in body tissues; the spleen, where they monitor antigens in the circulating blood; and the MALT, where they act as a defense against antigens in the mucosae and skin (4).

Structure

Cortical Area

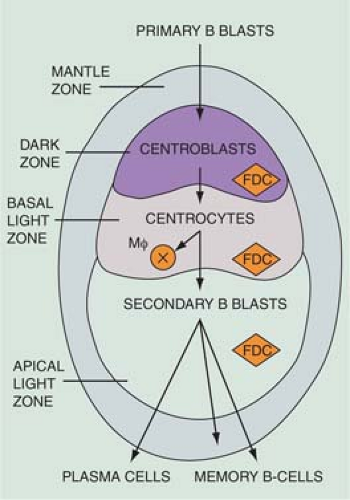

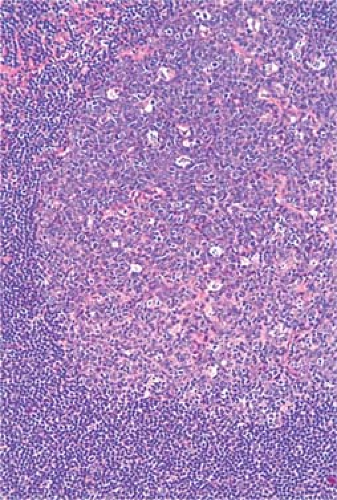

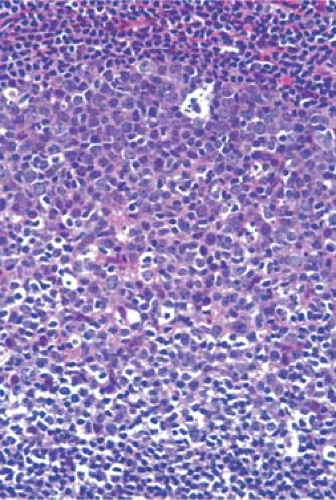

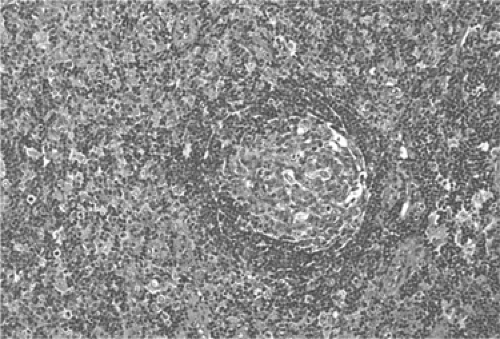

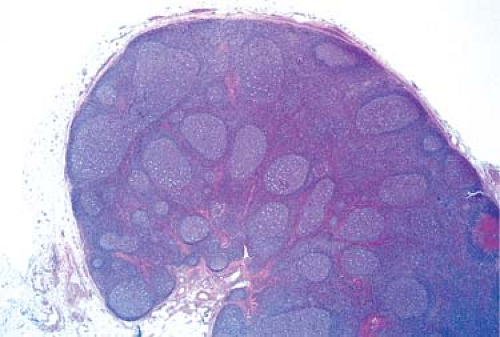

The cortical area, or superficial cortex (Fig. 1.3), includes the lymphoid follicles with their germinal centers. The cortical area represents the bursa-dependent, B-cell area of the lymph node, associated mainly with mechanisms of humoral immunity. The primary lymphoid follicles are round nodules, averaging 1 mm in diameter; the longer axis of each is oriented at a right angle to the lymph node capsule (5). The secondary or reactive lymphoid follicles comprise a peripheral area or mantle of closely packed, small lymphocytes and the centrally located germinal centers. The latter include a population of lymphoid cells in various stages of maturation, supportive reticulum cells, dendritic reticulum cells (DRCs), and histiocytes that often exhibit active phagocytosis. The germinal centers vary in size, enlarging substantially under conditions of antigenic stimulation (Fig. 1.4) The primary follicles are composed of a homogeneous cell population of small, darkly staining, inactive lymphocytes. They become secondary follicles when stimulated by antigens and include well-developed germinal centers composed of paler-staining, heterogeneous populations of cells. These predominantly include B lymphocytes, small and large, cleaved and noncleaved, in addition to a few scattered T lymphocytes (Fig. 1.5). The lymphocytes of the mantle zones are all of the B-cell type. The outer layers of the mantle zone are less tightly packed, and the cells, still of B-cell type, have more cytoplasm, and form the marginal zone. This zone, which appears distinct in the reactive follicles of the spleen, is not well formed in the lymph nodes, where it is often indistinguishable from the mantle zone because the cells of the two zones are mixed (6). The secondary follicles include in their reactive germinal centers the following types of cells: centroblasts, centrocytes, small lymphocytes, tingible-body macrophages, and DRCs. In their reactive phase, the germinal centers exhibit a dark zone oriented toward the center of the lymph node that is composed predominantly of centroblasts and a light zone oriented toward the periphery

of the lymph node that is composed predominantly of centrocytes. (Figs. 1.5,1.6,1.7,1.8). As they migrate through the germinal center, naive B-lymphocytes transform into centroblasts, which proliferate rapidly as shown by the numerous mitoses and by their immunostaining with the proliferation marker Ki-67 (7). They move to the light zone by differentiating into centrocytes, most of which die by apoptosis. The remnants of karyopyknosis and karyorrhexis are then engulfed by tingible-body macrophages that are scattered throughout the reactive germinal center, producing the characteristic starry-sky aspect. Centroblasts and centrocytes exclusively express the aminopeptidase CD10 (CALLA) marker (7). Centrocytes with unfavorable mutations resulting in low affinity for antigen are eliminated by apoptosis. In contrast, centrocytes with high-affinity Ig survive and progress further into differentiation toward memory cells or plasma cells. The memory cells migrate to the marginal zone, the plasma cells to the medulla and from there to various organs and tissues (7,8,9). The zonation and orientation of follicles is not always noticeable, being dependent on the phase of immune reaction and on the sectioning of the lymph node (8).

of the lymph node that is composed predominantly of centrocytes. (Figs. 1.5,1.6,1.7,1.8). As they migrate through the germinal center, naive B-lymphocytes transform into centroblasts, which proliferate rapidly as shown by the numerous mitoses and by their immunostaining with the proliferation marker Ki-67 (7). They move to the light zone by differentiating into centrocytes, most of which die by apoptosis. The remnants of karyopyknosis and karyorrhexis are then engulfed by tingible-body macrophages that are scattered throughout the reactive germinal center, producing the characteristic starry-sky aspect. Centroblasts and centrocytes exclusively express the aminopeptidase CD10 (CALLA) marker (7). Centrocytes with unfavorable mutations resulting in low affinity for antigen are eliminated by apoptosis. In contrast, centrocytes with high-affinity Ig survive and progress further into differentiation toward memory cells or plasma cells. The memory cells migrate to the marginal zone, the plasma cells to the medulla and from there to various organs and tissues (7,8,9). The zonation and orientation of follicles is not always noticeable, being dependent on the phase of immune reaction and on the sectioning of the lymph node (8).

Figure 1.1. The structure of the lymph node. From Stevens A, Lowe J. Lymph nodes. In: Stevens A, Lowe J. Histology. London: Gower Medical Publications, 1992: 90–95, with permission. |

Figure 1.4. Reactive lymph node with enlarged, irregularly shaped secondary follicles and germinal centers. Hematoxylin, phloxine, and saffron stain. |

Paracortical Area

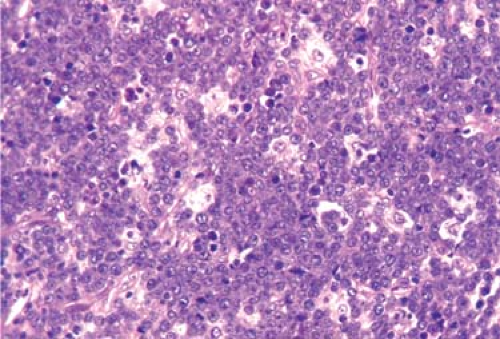

The paracortical area, or deep cortex (Fig. 1.9), is the densely cellular area beneath the cortex that extends between the lymphoid follicles, forming regular interdigitations from the capsule to the corticomedullary junction. It includes lymphoid cells and postcapillary venules. The paracortex represents the thymus-dependent area, and the lymphoid cells are predominantly of T-cell types. They have undergone differentiation in the cortex of the thymus by rearrangement of the T-cell receptor gene and then from the thymic medulla to the lymph node paracortex (7). They may be small or large, representing various stages of cellular transformation. Like B lymphocytes, they are mature, naïve lymphocytes that may become activated in response to antigenic stimulation (Fig. 1.10), change into immunoblasts and undergo active proliferation, or enter the pool of circulating lymphocytes (7). In addition to T cells, the paracortex contains the interdigitating cells (IDCs), which initially present antigens to lymphoid cells and thus play an essential role in initiating the immune response (4,8). When the IDCs are present in large numbers, the mixture of these larger, paler cells with the smaller, darker lymphocytes results in the typical “mottled” aspect of the reactive paracortical areas (Fig. 1.11).

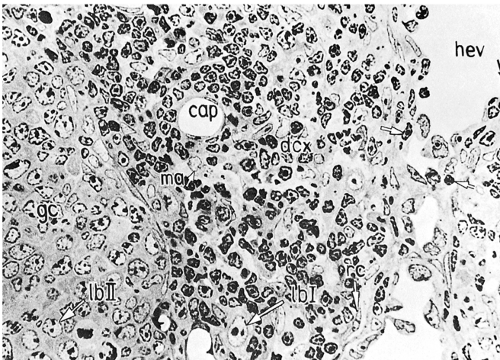

Medullary Area

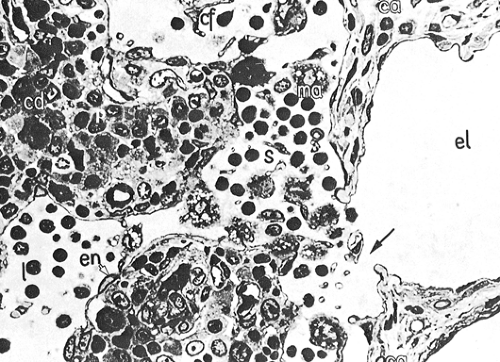

The medulla (Fig. 1.12) is the main site of plasma cell proliferation, differentiation, and production of antibodies. It is composed of cords of cells that include lymphocytes, plasmacytoid lymphocytes, plasmablasts, and mature plasma cells in various proportions. Under intense antigenic stimulation, the medullary cords may extend deep into the cortex.

The plasma cells lose their CD20 surface markers and synthesize antibodies that are carried by lymph into the general circulation. They contain intracytoplasmic immunoglobulins of various classes, with κ and λ light chains in a ratio of approximately 2:1 (8). The cords of plasma cells and their precursors are separated by wide medullary sinuses, which, in addition to the percolating lymph, also contain numerous monocytes, plasma cells, macrophages, and mast cells.

Cells

Lymphoid Cells

The lymph node parenchyma includes different populations of lymphoid cells in various stages of differentiation and activation lying on or moving through the supporting framework

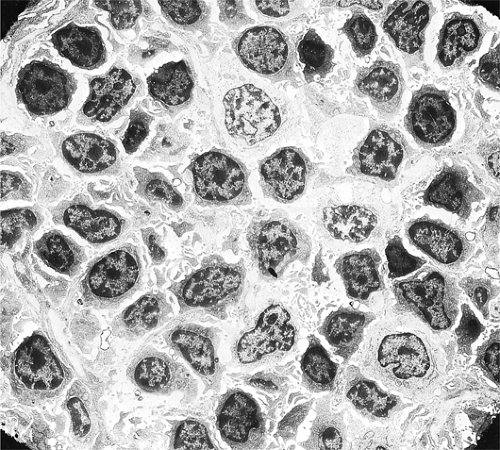

of the stroma. They comprise the main populations of B cells, T cells, and plasma cells, each with multiple subpopulations. The lymphoid cells include small, medium-sized, and large lymphocytes in various proportions (3). Small lymphocytes, also designated as mature or circulating lymphocytes, are nonactivated cells. They are the naïve B lymphocytes that populate the primary follicles and the mantle zones (9). After entering the lymph node through the postcapillary venules, if they do not become activated by encounter with antigen, they reenter the general circulation within a matter of hours via the efferent lymphatics (5). The cell diameter averages 6 μm and the diameter of the round nucleus is about 5 μm, so that the nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio is very high (1). Under light microscopy, the nucleus is dense and appears structureless, and the cytoplasm is just a thin, perinuclear rim. Under the electron microscope, the nucleus is formed almost entirely of highly condensed heterochromatin; the cytoplasm contains a large number of single ribosomes, a small Golgi body, several mitochondria, and few strands of endoplasmic reticulum (10,11,12) (Fig. 1.13). The surface shows shallow indentations and occasional short microvilli. Activated lymphocytes are considerably larger, have a greater amount of cytoplasm containing polyribosomes (11), a moderately large Golgi apparatus, multiple mitochondria, and a large nucleus with prominent nucleoli (Fig. 1.14). Medium-sized lymphocytes reflect the transition between nonactivated and activated lymphocytes. The B cells display on their surface membrane immunoglobulins that can be visualized by staining with fluorescein-labeled (Fig. 1.15) or peroxidase-labeled (Fig. 1.16) antihuman immunoglobulin antisera, in addition to strong complement (C3) receptors (13,14,15,16).

of the stroma. They comprise the main populations of B cells, T cells, and plasma cells, each with multiple subpopulations. The lymphoid cells include small, medium-sized, and large lymphocytes in various proportions (3). Small lymphocytes, also designated as mature or circulating lymphocytes, are nonactivated cells. They are the naïve B lymphocytes that populate the primary follicles and the mantle zones (9). After entering the lymph node through the postcapillary venules, if they do not become activated by encounter with antigen, they reenter the general circulation within a matter of hours via the efferent lymphatics (5). The cell diameter averages 6 μm and the diameter of the round nucleus is about 5 μm, so that the nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio is very high (1). Under light microscopy, the nucleus is dense and appears structureless, and the cytoplasm is just a thin, perinuclear rim. Under the electron microscope, the nucleus is formed almost entirely of highly condensed heterochromatin; the cytoplasm contains a large number of single ribosomes, a small Golgi body, several mitochondria, and few strands of endoplasmic reticulum (10,11,12) (Fig. 1.13). The surface shows shallow indentations and occasional short microvilli. Activated lymphocytes are considerably larger, have a greater amount of cytoplasm containing polyribosomes (11), a moderately large Golgi apparatus, multiple mitochondria, and a large nucleus with prominent nucleoli (Fig. 1.14). Medium-sized lymphocytes reflect the transition between nonactivated and activated lymphocytes. The B cells display on their surface membrane immunoglobulins that can be visualized by staining with fluorescein-labeled (Fig. 1.15) or peroxidase-labeled (Fig. 1.16) antihuman immunoglobulin antisera, in addition to strong complement (C3) receptors (13,14,15,16).

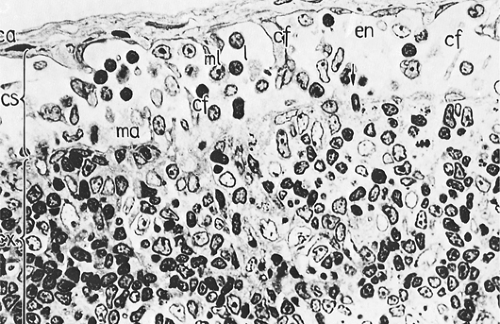

Figure 1.12. Medullary area (ma) of lymph node. Medullary cords (cd) with mature plasma cells (p); medullary sinus (s) in continuation with efferent lymphatic vessel (el). ca, capsule; cf, reticular fibers; en, sinus endothelium; l, lymphocytes. × 1,100. From Olah I, Röhlich P, Törö I. Lymph node. In: Ultrastructure of lymphoid organs. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott Co, 1975:216–255, with permission.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|