Overview

A middle-aged woman was admitted to the medical ward with a moderate case of pneumonia. After being started promptly on antibiotics and fluids, she stabilized for a few hours. But she deteriorated overnight, leading to symptoms and signs of severe hypoxemia and septic shock. The nurse paged a young physician working the overnight shift.

The doctor arrived within minutes. She found the patient confused, hypotensive, tachypnic, and hypoxic. Oxygen brought the patient’s oxygen saturation up to the low 90s, and the doctor now had a difficult choice to make. The patient, confused and agitated, clearly had respiratory failure: the need for intubation and mechanical ventilation was obvious. But should the young doctor intubate the patient on the floor or quickly transport her to the ICU, a few floors below, where the experienced staff could perform the intubation more safely?

Part of this trade-off was the doctor’s awareness of her own limitations. She had performed only a handful of intubations in her career, most under the guidance of an anesthesiologist in an unhurried setting, and the ward nurses also lacked experience in helping with the procedure. A third option was to call an ICU team to the ward, but that could take as long as transferring the patient downstairs.

After thinking about it for a moment, she made her decision. bring the patient promptly to the ICU. She called the unit to be ready. “In my mind it was a matter of what would be safest,” she reflected later. And so the doctor, a floor nurse, and a respiratory therapist wheeled the patient’s bed to the elevator, and then to the ICU.

Unfortunately, in the 10 minutes between notifying the ICU and arriving there, the patient’s condition worsened markedly, and when she got to the unit she was in extremis. After an unsuccessful urgent intubation attempt, the patient became pulseless. Frantically, one doctor shocked the patient while another prepared to reattempt intubation. On the third shock, the patient’s heart restarted and the intubation was completed. The patient survived, but was left with severe hypoxic brain damage.

The young physician apologized to the family, more out of empathy than guilt. In her mind, she had made the right decisions at the right time, despite the terrible outcome.

Nearly two years later, the physician received notice that she was being sued by the patient’s family, alleging negligence in delaying the intubation. The moment she received the news is seared in her memory—just like those terrible moments spent trying to save the patient whose family was now seeking to punish her. “I was sitting in the ICU,” she said, “and my partner calls me up and says, ‘You’re being sued. This system is broken, and that’s why I’m leaving medicine.’”1

Tort Law and the Malpractice System

The need to compensate people for their injuries has long been recognized in most systems of law, and Western systems have traditionally done so by apportioning fault (culpa). Tort law, the general legal discipline that includes malpractice law (as well as product liability and personal injury law), takes these two principles—compensating the injured in an effort to “make them whole” and making the party “at fault” responsible for this restitution—and weaves them into a single system. The linking of compensation of the injured to the fault of the injurer is brilliant in its simplicity and works reasonably well when applied to many human endeavors.2

Unfortunately, medicine is not one of them. Most errors involve slips—glitches in automatic behaviors that can strike even the most conscientious practitioner (Chapter 2)—that are unintentional and therefore cannot be deterred by threat of lawsuits. Moreover, as I hope the rest of this book has made clear, in most circumstances the doctor or nurse holding the smoking gun is not truly “at fault,” but simply the last link in a long error chain.

Here I am not referring to the acts of unqualified, unmotivated, or reckless providers who fail to adhere to expected standards and whose mistakes, therefore, are not unintentional errors but predictable damage deserving of blame. These situations will be discussed more fully in the next chapter, but the malpractice system (coupled with more vigorous efforts to hold the providers accountable and protect future patients) seems like an appropriate vehicle in dealing with such caregivers.

As an analogy, consider the difference between a driver who accidentally hits a child who darts into traffic chasing a ball and a drunk driver who hits a child on the sidewalk after losing control of his speeding car. Both accidents result in death, but the second driver is clearly more culpable. If the malpractice system confined its wrath to medicine’s version of the drunk, speeding driver—particularly the repeat offender—it would be hard to criticize it. But that is not the case.

Think about a doctor who performs a risky and difficult surgical procedure, and has done it safely thousands of time but finally slips. The injured patient sues, claiming that the doctor didn’t adhere to the “standard of care.” A defense argument that the surgeon normally did avoid the error, or that some errors are a statistical inevitability if you do a complex procedure often enough, holds little water in the malpractice system, which makes it fundamentally unfair to those whose jobs require frequent risky activities. As Alan Merry, a New Zealand anesthesiologist, and Alexander McCall Smith, Professor of Medical Law at the University of Edinburgh, observe, “All too often the yardstick is taken to be the person who is capable of meeting a high standard of competence, awareness, care, etc., all the time. Such a person is unlikely to be human.”2

The malpractice system is also ill suited to dealing with judgment calls, such as the one the physician made in choosing to wheel her septic patient to the ICU. Such difficult calls come up all the time. Because the tort system reviews them only after the fact, it creates a powerful instinct to assign blame (of course, we can never know what would have happened had the physician chosen to intubate the patient on the ward). “The tendency in such circumstances is to praise a decision if it proves successful and to call it ‘an error of judgment’ if not,” write Merry and McCall Smith. “Success is its own justification; failure needs a great deal of explanation.”

How can judges and juries (and patients and providers) avoid the distorting effects of hindsight and deal more fairly with caregivers doing their best under difficult conditions? Safety expert James Reason recommends the Johnston substitution test, which does not compare an act to an arbitrary standard of excellence, but asks only if a similarly qualified caregiver in the same situation would have behaved any differently. If the answer is “probably not,” then, as the test’s inventor Neil Johnston puts it, “Apportioning blame has no material role to play, other than to obscure systemic deficiencies and to blame one of the victims.”3,4

Liability seems more justified when rules or principles have been violated, since these usually do involve conscious choices by caregivers. But—in healthcare at least—even rule violations may not automatically merit blame. For example, even generally rule-abiding physicians and nurses will periodically need to violate certain rules (e.g., proscriptions against verbal orders are often violated when compliance would cause unnecessary patient suffering, such as when a patient urgently requires analgesia). That is not to condone healthcare anarchy—routine rule violations (Chapter 15) should cause us to rethink the rule in question, and some rules (such as “clean your hands before touching a patient” or “sign your site”) should virtually never be broken. But the malpractice system will seize upon evidence that a rule was broken when there is a bad outcome, ignoring the fact that some particular rules are broken by nearly everyone in the name of efficiency—or sometimes even quality and safety.

Tort law is fluid: every society must decide how to set the bar regarding fault and compensation. By marrying the recompense of the injured to the finding of fault, tort systems inevitably lower the fault-finding bar to allow for easier compensation of sympathetic victims. But this is not the only reason the bar tilts toward fault finding. Humans (particularly of the American variety) tend to be unsettled by vague “systems” explanations, and even more bothered by the possibility that a horrible outcome could have been “no one’s fault.” Moreover, the continuing erosion of professional privilege and a questioning of all things “expert” (driven by the media, the Internet, and more) have further tipped the balance between plaintiff and defendant. But it was already an unfair match: faced with the heart-wrenching story of an injured patient or grieving family, who can possibly swallow an explanation that “things like this just happen” and that no one is to blame, especially when the potential source of compensation is a “rich doctor,” or a faceless insurance company?5

The role of the expert witness further tips the already lopsided scales of malpractice justice. Almost by definition, expert witnesses are particularly well informed about their areas of expertise, which makes it exceptionally difficult for them to assume the mindset of “the reasonable practitioner,” especially as the case becomes confrontational and experts gravitate to more polarized positions.

Finally, adding to the confusion is the fact that doctors and nurses feel guilty for our errors (even when there was no true fault), often blaming ourselves because we failed to live up to our own expectation of perfection (Chapter 16). Just as naturally, what person would not instinctively lash out against a provider when faced with a brain-damaged child or spouse? It is to be expected that families or patients will blame the party holding the smoking gun, just as they would a driver who struck their child who ran into the street to chase a ball. Some bereaved families (and drivers and doctors) will ultimately move on to a deeper understanding that no one is to blame—that the tragedy is just that. But whether they do or do not, write Merry and McCall Smith, “It is essential that the law should do so.”2

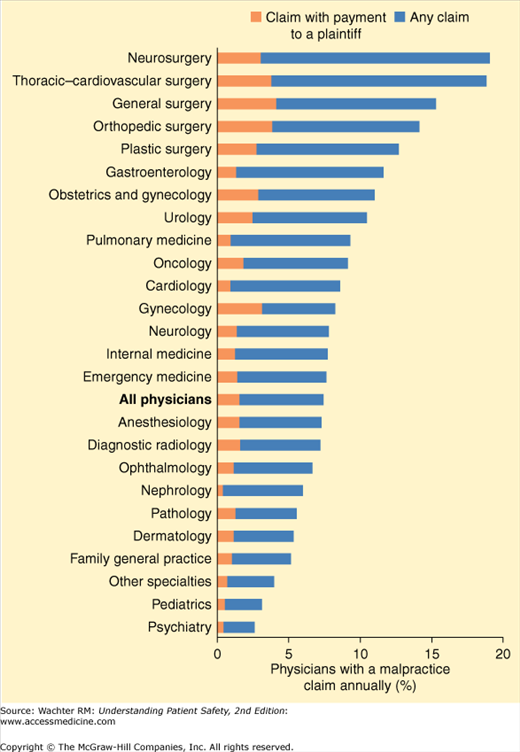

If the malpractice system unfairly assigns fault when there is none, what really is the harm, other than the payment of a few (or a few million) dollars by physicians, hospitals, or insurance companies to injured patients and families? I believe that there is harm, particularly as we try to engage rank-and-file clinicians in patient safety efforts. A 2011 study found that the vast majority of physicians are sued at some point in their careers, and nearly one in five physicians in the highest-risk fields (neurosurgery and cardiac surgery) is sued each year (Figure 18-1).6 Physicians, particularly in these fields, often become demoralized, and depressed providers are not likely to be enthusiastic patient safety leaders. Tort law is adversarial by nature, while a culture of safety is collaborative (Chapter 15). In a safety-conscious culture, doctors and nurses willingly report their mistakes as opportunities to make themselves and the system better (Chapter 14), something they are unlikely to do in a litigious environment.

This is not to say—as some do—that the malpractice system has done nothing to improve patient safety. Defensive medicine is not necessarily a bad thing, and some of the defensive measures taken by doctors and hospitals make sense. Driven partly by malpractice concerns, anesthesiologists now continuously monitor patients’ oxygen levels, which has been partly responsible for vastly improved surgical safety (and stunning decreases in anesthesiologists’ malpractice premiums) (Chapter 5). Nurses and physicians keep better records than they would without the malpractice system. Informed consent, driven to a large degree by malpractice considerations, can give patients the opportunity to think twice about procedures and have their questions answered (Chapter 21).

Unfortunately, in other ways, “defensive medicine” is a shameful waste, particularly when there are so many unmet healthcare needs. A 1996 study estimated that limiting pain and suffering awards would trim U.S. healthcare costs by 5% to 9% by reducing unnecessary and expensive tests, diminishing referrals to unneeded specialists, and so on.7 In today’s dollars, these savings would amount to over $300 billion a year.

In the last analysis, however, the way in which our legal system misrepresents medical errors is its most damning legacy. By focusing attention on smoking guns and individual providers, a lawsuit creates the illusion of making care safer without actually doing so. Doctors in Canada, for example, are five times less likely to be sued than American doctors, but there is no evidence that they commit fewer errors.1,8 And a 1990 study by Brennan et al. demonstrated an almost total disconnect between the malpractice process and efforts to improve quality in hospitals. Of 82 cases handled by risk managers (as a result of a possible lawsuit) in which quality problems were involved, only 12 (15%) were even discussed by the doctors at their departmental quality meetings or Morbidity and Mortality (M&M) conferences.9

What people often find most shocking about America’s malpractice system is that it does not even serve the needs of injured patients. Despite stratospheric malpractice premiums, generous settlements, big awards by sympathetic juries, and an epidemic of defensive medicine, many patients with “compensable injuries” remain uncompensated. In fact, fewer than 3% of patients who experience injuries associated with negligent care file claims. The reasons for this are varied, and include patients’ unawareness that an error occurred, the fact that most cases are taken by attorneys on contingency (and thus will not be brought if the attorneys think that their investment in preparing the case is unlikely to be recouped), and the fact that many of the uncompensated or undercompensated claimants are on government assistance and lack the resources, personal initiative, or social clout to seek redress. Thus, some worthy malpractice claims go begging while others go forward for a host of reasons that have nothing to do with the presence or degree of negligence.

Even when injured patients’ cases do make it through the malpractice system to a trial or settlement, it is remarkable how little money actually ends up in the hands of the victims and their families. After deducting legal fees and expenses, the average plaintiff sees about 40 cents of every dollar paid by the defendant. If the intent of the award is to help families care for a permanently disabled relative or to replace a deceased breadwinner’s earnings, this 60% overhead makes the malpractice system a uniquely wasteful business.

Error Disclosure, Apologies, and Malpractice

For generations, physicians and health systems responded with silence after a medical error. This was a natural outgrowth of the shame that most providers feel after errors (driven, in part, by the traditional view of errors as stemming from individual failures rather than system problems) and by a malpractice system that nurtures confrontation and leads providers to worry that an apology will be taken as an admission of guilt, only to be used against them later.

The cycle played out time and time again: patients who believed they had possibly been victims of medical errors wanted to learn what really happened, but their caregivers and healthcare organizations frequently responded with defensiveness, sometimes even stonewalling. This, in turn, made patients and families angry, frustrated, and even more convinced that they were on the receiving end of a terrible mistake. Hickson et al. found that nearly half the families who sued their providers after perinatal injuries were motivated by their suspicion of a cover-up or a desire for revenge.10

But could this cycle be broken? Until the patient safety field began, most observers would have said no. Each side, after all, appeared to be acting in its own interests: patients seeking information and ultimately redress, and providers and hospitals trying to avoid painful conversations and payouts. Yet the results were so damaging to everyone that some began wondering whether there was a better way. Since the patient safety movement emphasized the role of improving systems, could a change in the system, and mental model, alter the toxic dynamics of malpractice?

After losing two large malpractice cases in the late 1980s, the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Lexington, Kentucky, decided to adopt a policy of disclosure, apology, and early offer of a reasonable settlement, a policy it called “extreme honesty.” Perhaps surprisingly, they found that their overall malpractice payouts were lower than those of comparable VA institutions.11

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree