The Forensic Evaluation of Gunshot Wounds Associated With a Terrorist Event

William S. Smock

The United States has been forever changed by the domestic and international terrorist events on our soil over the last 10 years. In the aftermath of a terrorist incident involving U.S. citizens, its assets, or an assassination attempt on American leaders, either in this country or abroad, a forensic investigation will be swift and obligatory. Wound evaluations and evidence collection will be integral components of the law enforcement response. All patients, surviving and deceased, who are victims of blunt, blast, thermal, chemical, biological, radiological, or penetrating trauma will require a forensic evaluation to determine the nature of the injury and to document, collect, and preserve evidence.

Victims of gunshot wounding have unique forensic issues. The determination must be made as to whether a wound is an entrance or an exit wound. If possible, the projectile must be recovered, and a determination must be made as to the range of fire. Medical providers, from the tactical medic to the emergency physician, should understand the basic forensic principles associated with the assessment of gunshot wounds. The forensic lessons learned from the assassination of President Kennedy: from the treatment at Parkland Hospital, to the fallacious interpretation of wounds based on size, to the failure to have an autopsy performed by a forensic pathologist in Dallas, to the failure to document adequately the wounds photographically have all contributed to an example of how well-meaning medical providers can confound a criminal investigation of a gunshot wound. Failure of medical providers to identify, document, and analyze entrance and exit wounds, preserve short-lived evidence, and collect clothing and projectiles correctly could jeopardize future criminal and civil proceedings against both domestic and international terrorists (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11).

FORENSIC EVALUATION OF HANDGUN WOUNDS

The life of the patient and the medical care required to guard it obviously take precedence over the need for forensic evaluations and evidence collection. Yet it is possible for treating EMTs, paramedics, nurses, emergency physicians, and trauma surgeons to perform a forensic evaluation while providing lifesaving care (3,11). At a minimum, every gunshot wound should have its anatomical location accurately documented, its physical characteristics described, and associated short-lived evidence preserved (11,12).

Nonforensic medical providers should always avoid describing a wound as “entrance” or “exit.” Unfortunately, many practitioners enter forensic opinions into the medical records regarding wound type based solely on the size of the wound, assuming the large hole is the exit and the small hole is the entrance (1,13,14,15). Exit wounds, from handguns, are not consistently larger than their corresponding entrance wounds (11,15,16,17,18). The size of any wound, entrance or exit, is determined by multiple factors: the size, shape, configuration, and velocity of the projectile as it contacts or leaves the tissue and the physical characteristics of the tissue itself (17,18).

ENTRANCE WOUNDS

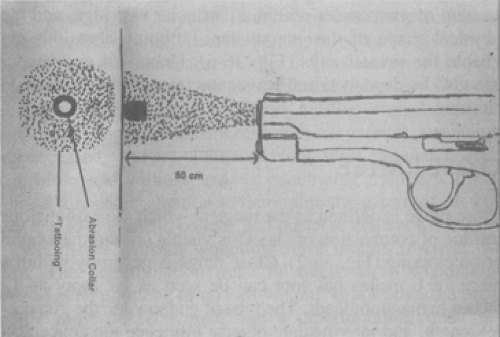

Gunshot wounds of entrance can be divided into four categories: distant or indeterminate range, intermediate range, close range, and contact. Each entrance wound category is based on the distance of the gun muzzle to the target and is called the “range of fire.” Each range-of-fire category is associated with specific wound characteristics: distant-range wounds have only an abrasion collar, intermediate-range wounds have an abrasion collar and tattooing, close-range wounds have an abrasion collar and soot, and contact wounds have seared skin, soot, and triangular-shaped tears of the skin (Table 36-1).

TABLE 36-1 Wound Characteristics of Entrance Wounds Based on the Range of Fire | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||

The size of the entrance wound bears no relationship to the caliber of the bullet, and physicians should never render opinions on caliber based on the size of the entrance wound (17,18). Depending on the elasticity of the epithelial tissue, entrance wounds may contract around or expand beyond the tissue defect caused by the bullet.

DISTANT WOUNDS

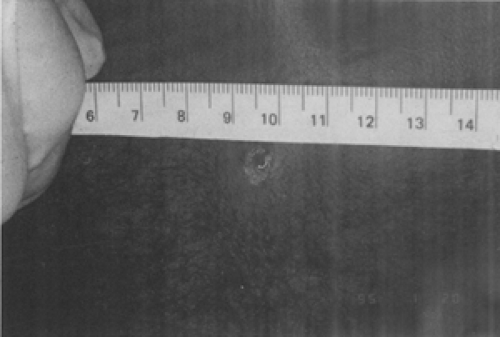

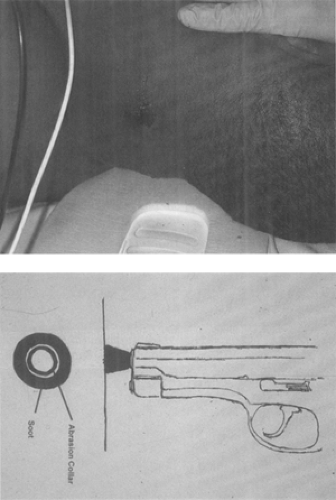

In a distant- or indeterminate-range entrance wound, only the bullet makes contact with the skin. As the bullet penetrates the skin, the friction between the projectile and the epithelial tissue creates an “abrasion collar” (Fig. 36-1). Abrasion collars vary in appearance depending on the angle of penetration (Fig. 36-2). All entrance wounds have an abrasion collar with the exception of those on the palms of the hands and the soles of the feet, where the epithelium is highly keratinized (17). Entrance wounds in these locations appear slitlike and lack the abrasion collar (Fig. 36-3). Other terms, which may be used interchangeably with “abrasion collar,” include “abrasion margin,” “abrasion rim,” and “abrasion ring.” Abrasion collars are a pure friction phenomenon and not the result of a so-called hot bullet.

INTERMEDIATE RANGE

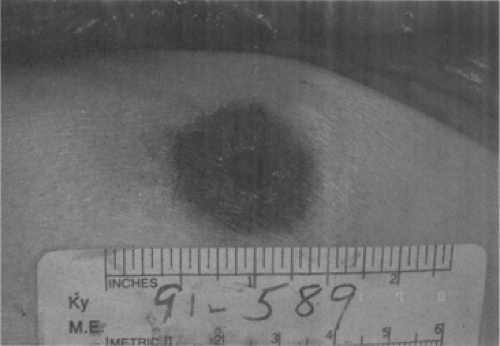

The intermediate-range wound is characterized by the presence of punctate abrasions, “tattooing” or “stippling” on the skin in the area of the abrasion collar (FIG. 36-4,FIG. 36-5). The tattooing is caused by unburned or partially burned pieces of gunpowder impacting the skin. Intermediate objects like clothing, furniture, or hair block the grains of gunpowder from making contact with the skin. Tattooing on the skin may be visualized from distances as close as 1/2 inch or as far away as 4 feet. The density and pattern of the punctate abrasions depend on the muzzle-to-skin distance, the length of the gun barrel, the presence of intermediate objects, the amount of gunpowder within a particular cartridge, and the physical shape of the gunpowder. Tattooing abrasions are visible for several days (Fig. 36-6). Unburned gunpowder can also be deposited and leave punctate nitrate residues on clothing.

CLOSE RANGE

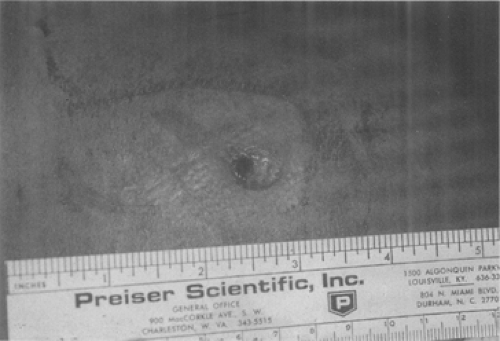

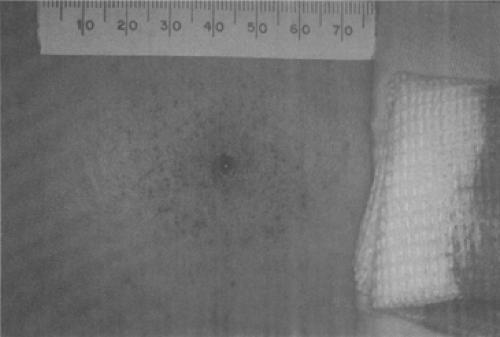

Close range is defined as the range at which the carbonatous residue of combustion or “soot” is visible around the wound or on clothing (Fig. 36-7). Close range is generally within a range of 6 inches but soot can be seen as far away as 12 inches in magnum loads. The type of gunpowder, the gun barrel length, and intermediate objects influence the concentration and pattern of soot. As in all entrance wounds, an abrasion collar or microtears are present, but with close-range

wounds it will be covered or obscured by the deposition of soot (Fig. 36-8). Soot is short-lived evidence and can be easily washed away in the rendering of patient care or surgical debridement of the wound. Do not describe soot as “powder burns.” This is an outdated term used to describe epithelial thermal injuries associated with the use of black powder that initiated a thermal event on the clothing of a victim. Black powder, as opposed to the smokeless powder of commercial ammunition, is found in muzzle-loader rifles, antique weapons, and in the blanks used in starter pistols.

wounds it will be covered or obscured by the deposition of soot (Fig. 36-8). Soot is short-lived evidence and can be easily washed away in the rendering of patient care or surgical debridement of the wound. Do not describe soot as “powder burns.” This is an outdated term used to describe epithelial thermal injuries associated with the use of black powder that initiated a thermal event on the clothing of a victim. Black powder, as opposed to the smokeless powder of commercial ammunition, is found in muzzle-loader rifles, antique weapons, and in the blanks used in starter pistols.

Figure 36-2. The width of the abrasion collar varies with the angle of the projectile’s impact. The trajectory of the projectile here is from right to left. |

Figure 36-3. Entrance wounds on the palms of the hands and the sole of the feet lack an abrasion collar due to the highly keratinized nature of the skin. |

Figure 36-4. “Tattooing” is the result of partially or unburned gunpowder striking the skin. The “tattoos” are punctate abrasions. |

Figure 36-5. Tattooing is associated with the intermediate range of fire. This patient was shot in the back at a distance of 12 inches by a 9mm Smith & Wesson, model 6906. |

Figure 36-6. The punctate abrasions may be present for days. This patient’s tattooing is easily visible 4 days postinjury. |

Figure 36-7. The deposition of soot surrounding this wound to the posterior neck is associated with a close range of fire, generally 6 inches or less. |

CONTACT WOUNDS

In a contact wound, the barrel is in contact with the victim’s clothing or skin. Contact wounds can be subdivided into “tight contact,” when the barrel is pushed hard against the skin or clothing, or “loose contact,” when the barrel is not in full contact with the skin and may be angled (Fig. 36-9). Wounds sustained in tight-contact woundings vary in appearance depending on the elasticity of the skin and the volume of gas injected. For example, a contact wound to the temple from a .22 caliber short cartridge appears as a small hole with seared blackened edges and only tiny triangle-shaped tears (Fig. 36-10). Compare the .22 caliber wound (Fig. 36-10) to a contact wound to the forehead from a .357 caliber magnum load (Fig. 36-11). The large volume of gas from a magnum load injected into scalp tissue results in a large, gaping stellate wound from a ripping and tearing of the skin. It is these large wounds that are frequently misinterpreted as exit wounds based solely on their size (13,14,15). Close examination of the wound margins of all contact wounds will reveal the presence of soot and seared skin from the discharge of hot gases and an actual flame (Fig. 36-12). In addition to the projectile and gases, soot and unburned gunpowder are also driven into the wound and can be recovered from the underlying tissue.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree