The Discovery of Acid

From antiquity to the 18th century

|

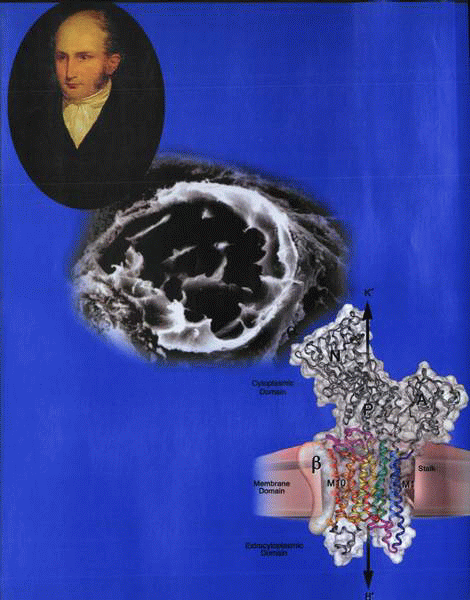

In the earliest times, physicians believed that the individual organs were the seats of separate spiritual agencies that in a divine manner controlled bodily function. Given the clearly perceived importance of food, the stomach was thus highly placed in the pantheon of lay regard. The ancient Greeks proposed that digestion was a process of concoction or heating, and, in this evolution, food was converted initially to chyle and then to the four humors (blood, phlegm, and yellow and black bile) before use by the mortal body. Hippocrates had, in fact, called the process of digestion pepsis and proposed that it was not dissimilar to the preparation of food by cooking. Galenic physiology proposed that successive cooking processes occurred sequentially in the stomach, intestine, and liver until food was finally converted into blood, and, indeed, such notions were commonly held until the eighteenth century.

The question of acid in the stomach

The early Greeks were not aware of acids in the modern sense of chemistry but identified them only as bitter-sour liquids. Diocles of Carystos (circa 350 BC) specified sour eruptions, watery spitting, gas, heartburn, and epigastric hunger pains radiating to the back (with occasional splashing noises and vomiting) as symptoms of illness originating in the stomach. Three hundred years later, Celsus (30 BC-25 AD), although more an encyclopedist than a physician, recognized that certain foods were acidic and recommended that “if the stomach is infested with an ulcer …, light and gelatinous food must be used … and everything acrid and acid is to be avoided.”

There appears to have been little further development in understanding the function of the stomach and the real nature of digestive processes until the sixteenth century. Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim (also known as Paracelsus) was born in Ensiedeln near Zürich in 1493. He was an alchemist-physician and a proponent of chemical pharmacology and therapeutics who had enormous influence on the medical thinking of his day. Indeed, the origin of modern rational therapeutic strategy may be regarded as having been initiated by Paracelsus.

Paracelsus believed that there was acid in the stomach and that its presence was necessary for digestion, although he asserted that it was ingested. This conviction that gastric acid was of extracorporeal origin would, of course, subsequently be proven to be wrong. Nevertheless, he recognized the importance of chemistry and its relation to disease, rejecting Galenism and the mysticism of humors and health and insisting on the development of rational rather than alchemic strategies for symptom or disease management.

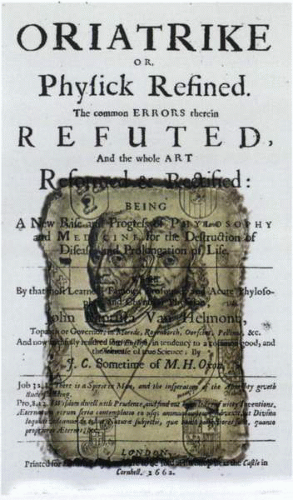

Jean Baptiste van Helmont (1577-1644) of Belgium founded the Iatrochemical School. This maintained that the principal archeus, Blas, was controlled by the sensitive and motive soul, anima sensitiva motivaque, in the “pit of the stomach” (solar plexus). From this site, all chemical physiologic processes were regulated. He believed that digestion began in the stomach by the intermittent fermentation of acid and that, thereafter, a number of other fermentation processes took place, including that of bile in the duodenum. In further observations, he recognized that

acid alone did not decompose food in vitro, and he postulated the existence of another agent typified as a ferment. In this respect, his prescience was noteworthy in first considering the concept of an enzyme adjunct to the digestive process.

acid alone did not decompose food in vitro, and he postulated the existence of another agent typified as a ferment. In this respect, his prescience was noteworthy in first considering the concept of an enzyme adjunct to the digestive process.

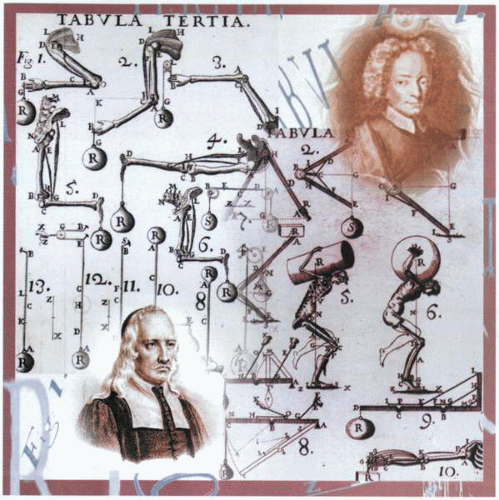

The Iatromathematical School

The chemical views propounded by Paracelsus, van Helmont, and others were strongly opposed by the Iatromathematical School, which maintained that all physiologic happenings should be treated as fixed consequences of the laws of physics. This group included such individuals as Descartes, Borelli, Sanctorius, Pitcairn, and Boerhaave, all noteworthy for their intellectual and philosophical contributions to medicine and science.

Thus, Borelli (1608-1679) and his disciples favored the view that the stomach was but a mechanical mill, grinding up its contents into chyme. Mobius denied the existence of gastric acid, and Archibald Pitcairn interpreted all function in terms of mechanical activity, believing the teeth to be scissors, the stomach a fermenting vat, and the lungs and heart to be bellows and a pump, respectively.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree