The Anal Canal

ANATOMIC AND HISTOLOGIC CHARACTERISTICS

Terminology Used for the Anus, Distal Rectum, and Perianal Skin and Problems with These Terms

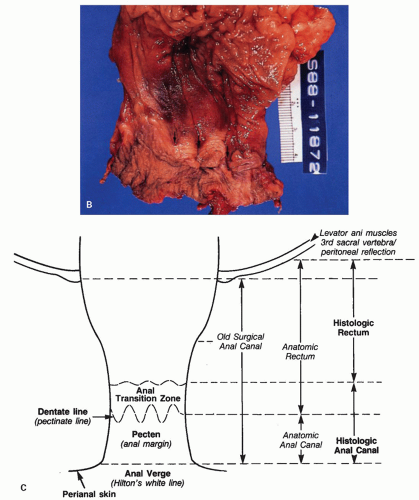

There are numerous terms applied to the anal canal (see terminology at the end of the chapter), but the only important one is that relevant to tumors. This includes the dentate line; the transitional mucosa that extends proximally for a variable distance, which varies from millimeters to a few centimeters, but cannot be seen with the naked eye; and the squamous mucosa distal to the dentate line.

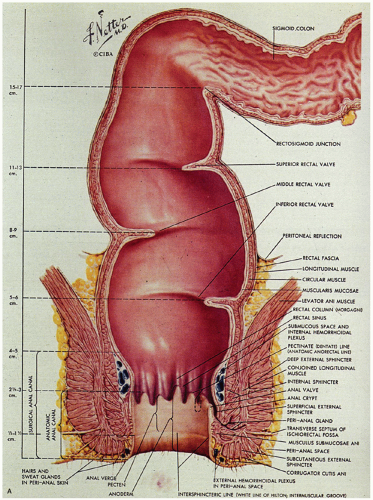

Critical terms that are used for various anatomic components that are helpful in understanding the anatomy and histology of this region are as follows (Fig. 21-1):

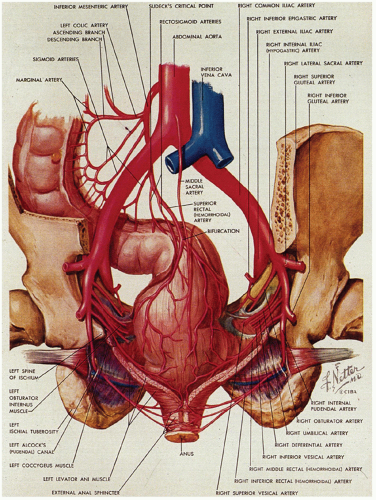

Figure 21-1. (Continued) The dentate line can be seen coursing across the specimen. Beneath it is the pecten and above it is the ATZ in which the anal valves can be seen as pockets (arrowheads) going down into the anal sinuses behind the dentate line. Between the anal valves (semilunar) are the columns of Morgagni. There is a poorly defined transition between the lower rectal mucosa and the ATZ. Anal gland ducts open into this junction, section of which is shown in Figure 21-4C. Diagram depicting the different definitions of the anal canal together with the “histologic” anal canal, which is the one conventionally used medically. (Figure 22-1A from © 1962 Ciba-Geigy Corp. Reproduced from the Ciba collection of medical illustrations by Frank H. Netter, M.D. All rights reserved, with permission.) |

Dentate line (also called the pectinate line): The single, reproducible, constant, but wavy line that runs circumferentially around the anal mucosa and is formed by the anal valves, sinuses, and bases of the anal columns.

Pecten: The smooth, nonhairy zone extending between the dentate line and the hair (and sweat gland)-bearing perianal skin (which was originally said to start at Hilton’s white line).

Anal transition zone (ATZ): The zone between uninterrupted colorectal-type mucosa above and uninterrupted squamous epithelium below, irrespective of the type of epithelium present in the zone itself.1 Practically, this is the noncolumnar epithelium from the dentate line upward until large bowel mucosa is encountered.

Surgical anal canal: This was originally that part of the distal intestinal tract enclosed by the internal

sphincter muscle but is a useless concept, since it includes most of the distal rectum, the entire anus, and even some perianal skin.

Anatomic anal canal: Begins at the dentate line and extends out to the anal verge (beginning of the perianal skin). The ATZ is therefore excluded from this definition. This is a good reason to abandon the term.

Anatomic rectum: That part of the large bowel from the third sacral vertebra body, or more sensibly the peritoneal reflection, down to the dentate line, and therefore includes the ATZ, thereby incorporating a part of the anus. This is a good reason to abandon the term.

Histologic anal canal: The ATZ and pecten together, which is largely surrounded by the external sphincter muscle. The corollary of this is the histologic rectum, namely, that part of the large bowel from the level of the third sacral vertebra, or the peritoneal reflection, down to the ATZ. The specific epithelial types are discussed under the section “Microscopic Anatomy” below.

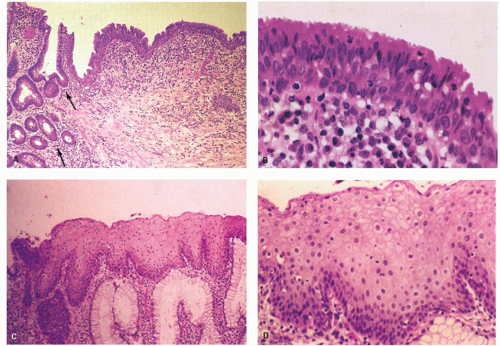

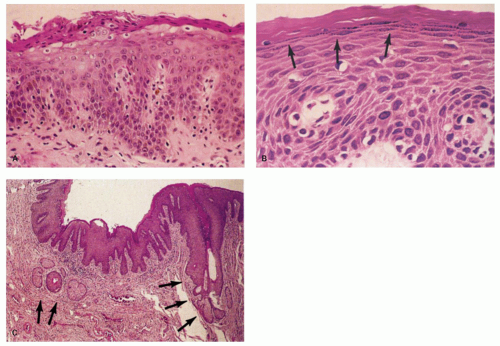

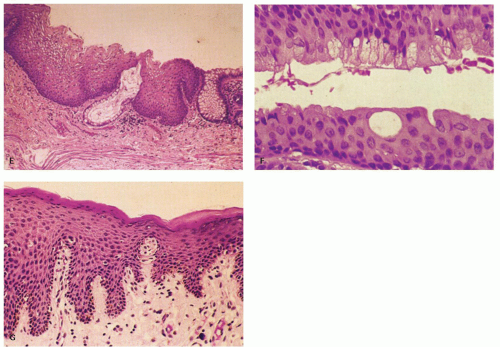

There is much confusion over the normal anatomy and histology of the anal canal for a variety of reasons. This is primarily because of the persistent use of terminology that has become obsolete but which is still perpetuated. We attempt to walk you safely through this minefield. The one landmark to which all definitions (and problems) need to be related is the dentate line, also known as the pectinate line, which is the single, reproducible, constant, but wavy line that runs circumferentially around the anal mucosa and which is easily visible in the opened, resected specimen (Fig. 21-1) or on retroflexion of the endoscope at sigmoidoscopy; it marks the embryologic junction between the cloaca above and the proctodeum below. It is at the lowest part of the anal transitional zone (ATZ), which is lined largely by transitional or squamous mucosa that extends upward for a variable distance before becoming colorectal mucosa (Fig. 21-2). The more commonly used name for the line is dentate, not pectinate, and that is the name used throughout the rest of this chapter. Immediately below the dentate line is the nonhair pecten (Fig. 21-3) (or anal

margin—another term we could do without), which is covered by moist, nonkeratinizing squamous mucosa, similar to that in the mouth and vagina, and which continues down to merge imperceptibly with the hair-bearing perianal skin (Fig. 21-3).

margin—another term we could do without), which is covered by moist, nonkeratinizing squamous mucosa, similar to that in the mouth and vagina, and which continues down to merge imperceptibly with the hair-bearing perianal skin (Fig. 21-3).

Figure 21-2. (Continued) E: A third junction with interdigitating rectal and squamous mucosa. F: ATZ, which contains individual goblet cells and groups of mucin-producing cells. G: There is occasionally a transition from nonkeratinizing to keratinizing squamous epithelium in this ATZ (see Fig. 21-3A,B). |

The surgical anal canal is defined as that part of the distal intestinal tract enclosed by the internal sphincter muscle, namely, from the levator ani muscles of the pelvic floor above to the skin of the anal verge below. This definition, attributed to Symington in 1888,2 certainly made life easy for practicing surgeons, who can see the levators from either direction. It is probably already apparent that the concept of the surgical anal canal has at least two major drawbacks:

1. It includes the rectum, which is a separately recognized part of the gut with clear definitions of its location.

2. In classifying tumors of this region, we ignore the concept of the surgical anal canal and its all-inclusive mucosae and skin. Thus, using the definition of surgical anal canal literally, we should call many rectal adenocarcinomas adenocarcinomas of the anal canal, which we obviously do not, because we use the definition of anatomic rectum to classify them. We include squamous mucosa of the ATZ and pecten in our concept of anal carcinomas, because they arise in the most distal part of the gut, which we call the anus. Nevertheless the AJCC also defines the anal canal as extending from the apex of the anal sphincter complex to the palpable intersphincteric groove at the distal edge of the internal sphincter muscle. This may be useful in patients, but is tough to translate to histology in an opened abdomino-perineal resection.

The obvious solution is to utilize the concept of the histologic anal canal, which extends from the termination of rectal mucosa to the perianal skin. It includes the ATZ and pecten. The histologic anal canal is largely surrounded by the external sphincter muscle. Everything that is lined by the rectal epithelium is assumed to be rectal, and all adenocarcinomas arising from this mucosa are, by definition, rectal. Using this definition of the histologic anal canal, carcinomas arising in the mucosa of the ATZ, from the dentate line up to the junction with rectal mucosa, should be included in carcinomas of the anal canal as the transition zone is the proximal part of the anal canal. Those arising from the squamous pecten immediately below the dentate line are also included in carcinomas of the anal canal. Finally, carcinomas arising in the hair-bearing perianal skin are called carcinomas of the perianal skin (logic wins in the end).

Distally, the pecten merges imperceptibly with the perianal skin. In the late 19th century, Hilton thought that he could see this junction, as marked by the white line that bears his name.3 However, there is no histologic counterpart to this line, and in many but not all patients, it is indiscernible; the term has therefore largely fallen out of use. This junction is, however, marked grossly by a change over a few centimeters during which the skin becomes more pigmented and bears hairs, gradually becoming the skin of the anal verge and the perianal region; the same changes are reflected histologically, but keratinization also occurs in the perianal skin.

With this insight, let us take a more detailed look at the remaining anatomic structures and microscopic appearance of the anal canal.

Surface Anatomy

The anal canal develops from the keratinizing proctodeum distally and the nonkeratinizing cloaca proximally, their junction being the site of the dentate line. We include all of these in the histological anal canal. Immediately above the dentate line, 6 to 10 longitudinally oriented anal columns (of Morgagni) may be visible merging with the rectal mucosa above, particularly in young patients (Fig. 21-1). They may disappear with age. These columns are joined at their bases by small semilunar valves, which form papillae, and these structures define the dentate line. The dentate line may be difficult to identify when valves and papillae are not readily identified; it is then best defined by the opening of the lowest visible sinus. Immediately behind the columns, small pockets, the anal sinuses (or crypts), may be found. Some of the openings of the anal ducts and their glands (Fig. 21-4) are into these sinuses, but occasionally they are found further up the transition zone. The proximal extent of the ATZ is the rectum, and the junction between the two mucosae can usually be appreciated grossly because of the pink color to the rectum and the more gray color of the ATZ.

Distal to the dentate line, the squamous-lined pecten is smooth, whitish, and shiny in life, but in resected specimens that have been pinned out, it is often transversely wrinkled, and the wrinkling may extend up into the transition zone. The junction between pecten and perianal skin often is not

sharp but is marked grossly by a change over a few centimeters during which the skin becomes more pigmented and bears hairs, gradually becoming the skin of the anal verge and the perianal region.

sharp but is marked grossly by a change over a few centimeters during which the skin becomes more pigmented and bears hairs, gradually becoming the skin of the anal verge and the perianal region.

Musculature

This is far easier to see in diagrams than it is to demonstrate anatomically (Figs. 21-1A and 21-4A). It consists of three parts. The first is the internal anal sphincter, which is a continuation and modification of the circular muscle of the rectum. This is largely surrounded by the external sphincter muscle, the second part of the anal musculature, which has subcutaneous, superficial, and deep parts. The subcutaneous part is immediately related to the perianal skin and the most external parts of the anal canal. The superficial part sweeps around to reinforce the bulk of the internal sphincter on all sides, and the deep part runs into the third part of the anal musculature, the levator ani, which is attached to the lateral pelvic walls. Part of this is the sling of muscle called puborectalis, which causes angulation of the rectum, partially preventing incontinence. This sling of muscle is held in place posteriorly by the anococcygeal ligament and anteriorly is inserted into the perineal body.

Blood Supply

The blood supply of the upper part of the anal canal comes from the inferior mesenteric artery through its termination in the superior rectal artery (Fig. 21-5). The latter bifurcates on the posterior surface of the rectum, each branch passing laterally (the lateral rectal arteries), piercing the muscle at several sites to enter the submucosa down to the level of the columns of Morgagni. The middle sacral artery arises from the posterior wall of the aorta immediately above its bifurcation and supplies a branch to the posterior rectal wall. The distal anal vasculature comes primarily from the internal pudendal arteries, which divide into the inferior rectal artery and several other branches that supply the sphincter muscles and then the mucosa. These anastomose with branches from the lateral rectal arteries and the gluteal and perineal arteries.

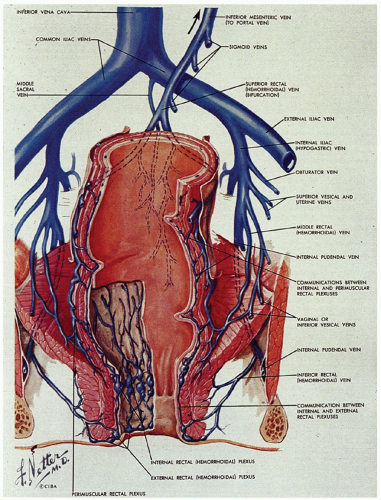

The venous system is of greater clinical significance in view of its frequent dilatation to form hemorrhoids. Two major submucosal venous plexuses are present, the internal and external, which communicate with each other across the dentate line (Fig. 21-6).4 The internal hemorrhoidal plexus is located immediately above the dentate line. On penetrating the muscularis propria, there is a third perimuscular rectal plexus of veins. Most of the veins from this plexus drain up through the superior rectal vein into the portal circulation via the inferior mesenteric vein, but there is also a well-defined anastomosis with the external hemorrhoidal plexus, which is located distal to the dentate line. The greatest concentration of veins is immediately above the dentate line in the columns of Morgagni, and it is these veins and/or those of the external plexus that enlarge and prolapse and may ultimately undergo all of the complications of hemorrhoids. For this reason, excision of internal hemorrhoids invariably includes part of the dentate line and the accompanying transitional epithelium. The external hemorrhoidal plexus is also submucosal and drains through the inferior and middle hemorrhoidal veins back into the internal pudendal veins, and thence into the internal iliac veins and vena cava. In addition, the communications between the internal and external hemorrhoidal plexus form an anastomosis between the portal and systemic venous systems, so that hemorrhoidal bleeding may be a reflection of portal hypertension.

Lymphatic Supply

Lymphatic drainage from the pecten is primarily to the inguinal and from there to the iliac nodes. Above the dentate line, lymphatics go to both to the internal iliac nodes and the inferior mesenteric nodes, the latter via the lateral (perirectal) and superior rectal artery groups of nodes. Tumors of the anal canal therefore always require careful observation of these groups of nodes. Fortunately, the inguinal nodes are superficial and therefore accessible to fine needle aspiration, biopsy, or excision.

Microscopic Anatomy

From proximal to distal, the epithelial types found in the distal rectum and anal canal are the following.

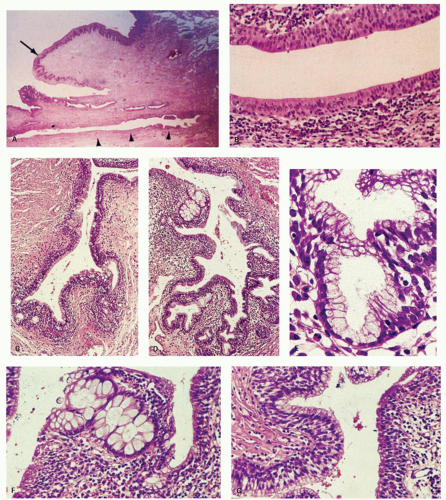

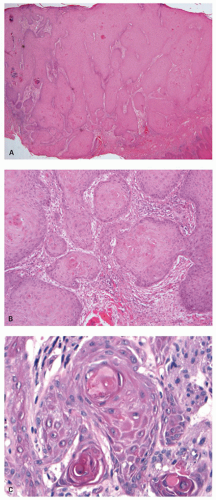

Columnar zone. It is the most distal part of the histologic rectum but included in some of the archaic definitions of the anal canal (see previous discussion). It consists of typical colonic crypts; however, the last centimeter or so often appears atrophic, with thin mucosa and a reduced number of crypts that may also be bifid (Fig. 21-2). Further, occasional crypts may be found in isolation within the ATZ; although by light microscopy these often appear to be buried beneath the transitional epithelium (Fig. 21-2C), by scanning electron microscopy, they open onto the surface, forming typical but isolated crypt units virtually identical to their more proximal counterparts.4 Occasionally, Paneth cells may be found in the crypts embedded within the transition zone. Rarely, the

crypts appear to be more like pyloric glands and may even have fundic gland mucosa complete with parietal cells.5 These metaplasias are probably a reaction to injury, although the presence of parietal cells suggests that they may be heterotopic mucosa.

crypts appear to be more like pyloric glands and may even have fundic gland mucosa complete with parietal cells.5 These metaplasias are probably a reaction to injury, although the presence of parietal cells suggests that they may be heterotopic mucosa.

Anal transition zone. This zone extends from the crypt-bearing distal rectal mucosa above to the uninterrupted pectinate squamous mucosa below. The ATZ usually reaches 0.5 to 1 cm above the dentate line. It is sometimes very short and on occasion may not be present at all, although that is unusual.6 On the other hand, it may extend as much as 20 mm above the dentate line to 6 mm below it. The typical ATZ epithelium bears a superficial resemblance to urothelium (hence “transitional”). It consists of four to nine layers of cuboidal cells with their nuclei oriented perpendicular to the basement membrane (Fig. 21-2). However, the superficial cells can be flattened, cuboidal, polygonal, resemble umbrella cells of the bladder, or columnar. In ultrastructural studies, it was found to share features of squamous epithelium and urothelium. The length of the ATZ lined by transitional epithelium varies greatly from one person to another, and in the ATZ it may be mixed with rectal crypts proximally and mature squamous epithelium, especially distally. The amount and distribution of each epithelium in the ATZ is totally unpredictable. Really rarely, the transition zone may be lined by simple columnar mucosa resembling gastric surface epithelium but with larger ATZ.7 If a histologic section is taken through an apparent junction between rectal mucosa and the ATZ, the transitional-type epithelial sometime extends proximally much further than anticipated macroscopically, and the rectal mucosa may extend more distally. Sometimes transitional-type mucosa may also extend distally for a few millimeters beneath the dentate line.

Squamous zone distal to the dentate line. This consists of nonkeratinizing squamous mucosa with short, stubby stromal papillae but no skin appendages. Distally the mucosa contains increased numbers of melanocytes, and at some point it forms a granular layer with subsequent keratinization (Fig. 21-3).

Perianal skin. This is keratinized squamous epithelium typical of skin with appendages, primarily hair follicles, sebaceous glands, and apocrine glands. The epidermis has well-developed papillae and prominent melanocytes (Fig. 21-4).

Anal ducts and glands. These are tubular structures that extend from the ATZ into the stroma, including the internal sphincter muscle at the level of the dentate line. Their lining is as unpredictable as is the ATX epithelium. The ducts may be lined by transitional epithelium, pseudostratified epithelium resembling Fallopian tube epithelium, but without cilia, and goblet cells may be scattered around as well. The glands are simple tubular mucous glands that empty into the ducts (Fig. 21-5). We have seen a few cases in which the glands contain typical prostatic glandular epithelium. The ducts open into the anal valves and sinuses at the level of the dentate line and often above. At the lower end of the ATZ a further series of simple perianal glands are occasionally found. These glands secrete a mixture of sulfomucins and sialomucins8 that forms a thin layer over the ATZ.4

Nerves and Biopsy Implications for Hirschsprung’s Disease

The upward extension of squamous epithelium from the dentate line has distinct implications if suction biopsy is being carried out for possible Hirschsprung’s disease. It is well known that the most distal part of the large bowel immediately above the dentate line is normally relatively deficient in ganglion cells and may also have thickened nerve trunks, thereby mimicking the changes found in Hirschsprung’s disease. For this reason, it is always advocated that biopsies be taken at least 2 cm above the dentate line. When biopsies contain both changes in the nerves, suggesting Hirschsprung’s disease but also transitional zone epithelium, the only sensible conclusion is that the specimen is too far distal for diagnostic purposes and that the biopsy should be repeated.

DEVELOPMENTAL ABNORMALITIES

These occur in about 1/5,000 live births, with a slight excess in males; only about 5% occur in siblings or twins. Most abnormalities are the result of malformations at the time the cloaca fuses with the urorectal septum, ultimately separating the bladder from the large bowel at about 7 weeks of gestation, or failure of the anal membrane to disappear at about 12 weeks of gestation.

There have been numerous attempts to classify anorectal anomalies, starting with that of Ladd and Gross in 1930 and continuing into the mid-1960s.9 Most were based on those high and low anomalies, supposedly resulting from persistence or incomplete disappearance of the anal membrane, which accounted for 10% to 30% of the anomalies found; incomplete disappearance (type I—congenital anal stenosis) or persistence (type II—membranous imperforate anus); and being separated from those with high anomalies,

by far the most common being type III, accounting for 65% to 90% of anomalies and consisting of a blind-ending rectum and imperforate anus. Rarely, the bulbous analis failed to develop (type IV). It was appreciated that high, rather than low, anomalies were much more likely to be associated with fistulas and a variety of other anomalies including genitourinary and cardiac diseases, other atresias, and vertebral anomalies including sacral agenesis.10, 11

by far the most common being type III, accounting for 65% to 90% of anomalies and consisting of a blind-ending rectum and imperforate anus. Rarely, the bulbous analis failed to develop (type IV). It was appreciated that high, rather than low, anomalies were much more likely to be associated with fistulas and a variety of other anomalies including genitourinary and cardiac diseases, other atresias, and vertebral anomalies including sacral agenesis.10, 11

However, it became apparent that when the anus was abnormally located, it frequently was not blind but communicated with either the urogenital tract or the perineum by a fistula that was both functional and lined by a mucosa that was indistinguishable from the ATZ and surrounded by a cuff of smooth muscle. It thus had the appearance of an ectopic and usually hypoplastic anus. The classification of this group of disorders now in general use is the International Classification developed by Santulli et al.,12 which divides them into low, intermediate, high, and miscellaneous categories but includes the site of the anal opening, the presence of fistulae, the organs involved, and the differences between males and females, as shown in Table 21-1.

Some cases of anal atresia are part of the vertebral defects, anal atresia (imperforate anus), tracheoesophageal fistula with esophageal atresia, and radial dysplasia (VATER) association, sometimes in association with renal or cardiovascular anomalies.13 Less commonly, there may be absence of anal, genital, and urinary orifices.14 A variety of other case reports exist in the literature associating anorectal abnormalities with numerous other abnormalities. While of interest, it is currently unclear whether these represent positive associations or chance associations with other anomalies.

Table 21-1 Classification of Anorectal Anomalies | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||

HEMORRHOIDS

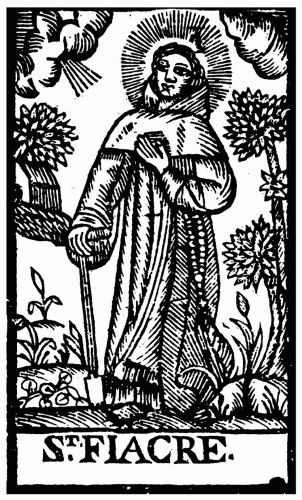

Hemorrhoids have been known to exist for thousands of years, the term being derived from the Greek words for blood (haima) and flowing (rhois). The Latin equivalent is pila (a ball) from which the term “piles” is derived. In view of their nuisance value and chronic debilitating nature where they may dominate lifestyle, it is not surprising that there is even a patron saint for hemorrhoid sufferers. St. Fiacre was an Irish monk who lived in the Brie region of France (Fig. 21-7). His numerous miraculous powers included healing, but he inherited his baptismal name from “fic—a kind of wart or growth which gives off a smelly liquid …

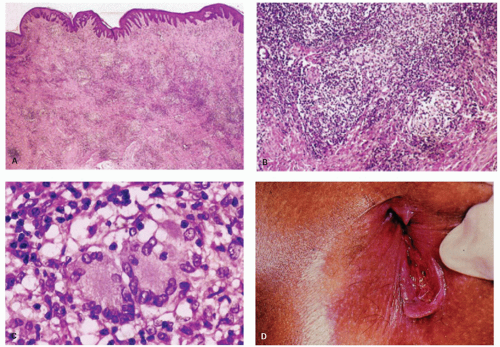

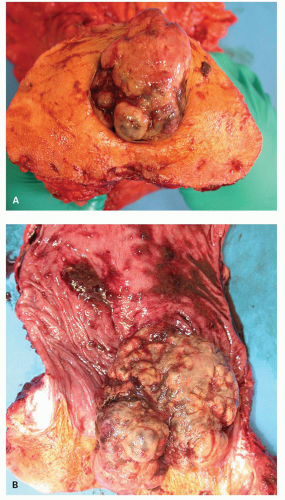

usually in the behind and the shameful parts of the body.” Many are said to have been cured after praying at his shrine.15 Hemorrhoids are polyps or masses composed primarily of veins and capillaries and sometimes arterioles in the anal canal and immediate perianal region. They are thought to be present in at least half of the US population by age 50. They are conventionally divided into two types. Internal hemorrhoids originate from the superior (internal) hemorrhoidal plexus immediately above the dentate line. By contrast, external hemorrhoids are varicosities of the inferior (external) hemorrhoidal plexus, which lie below the dentate line. Because of the communication between the internal and external hemorrhoidal plexuses, which tend to increase with age, most patients have both internal and external hemorrhoids. Traditionally, hemorrhoids projecting into the anal canal are called first-degree, those that prolapse with defecation but reduce spontaneously are called second-degree, those that require manual reduction are called third-degree, and those that cannot be reduced are called fourth-degree.

usually in the behind and the shameful parts of the body.” Many are said to have been cured after praying at his shrine.15 Hemorrhoids are polyps or masses composed primarily of veins and capillaries and sometimes arterioles in the anal canal and immediate perianal region. They are thought to be present in at least half of the US population by age 50. They are conventionally divided into two types. Internal hemorrhoids originate from the superior (internal) hemorrhoidal plexus immediately above the dentate line. By contrast, external hemorrhoids are varicosities of the inferior (external) hemorrhoidal plexus, which lie below the dentate line. Because of the communication between the internal and external hemorrhoidal plexuses, which tend to increase with age, most patients have both internal and external hemorrhoids. Traditionally, hemorrhoids projecting into the anal canal are called first-degree, those that prolapse with defecation but reduce spontaneously are called second-degree, those that require manual reduction are called third-degree, and those that cannot be reduced are called fourth-degree.

Hemorrhoids tend to be located primarily in the patient’s right anterior, right posterior, and left lateral positions, but small or secondary hemorrhoids may occur between them.16 These positions correspond to those of the anal cushions, which are seen normally on anoscopy when the anal canal forms a slightly bent-over Y, producing the three cushions.

Pathogenesis

Hemorrhoids tend to be a disease of Western society and have been traditionally associated with a low-residue diet. It has been noted that hemorrhoids are relatively uncommon in the Third World countries and are virtually unknown in animals, suggesting that straining to pass hard stool plays a role. In addition, the underlying elastic and connective tissue may lose its abilities to recoil with aging. Prolapse may be potentiated by hyperactivity of the internal sphincter muscle. Although they are traditionally thought of as dilated varicose veins of the hemorrhoidal plexus, bleeding from them is characteristically bright red, suggesting that they may be a variation of arteriovenous fistula reminiscent of erectile tissue.17, 18 In older patients and particularly in women, hemorrhoids may be associated with anal prolapse.

Clinical Features

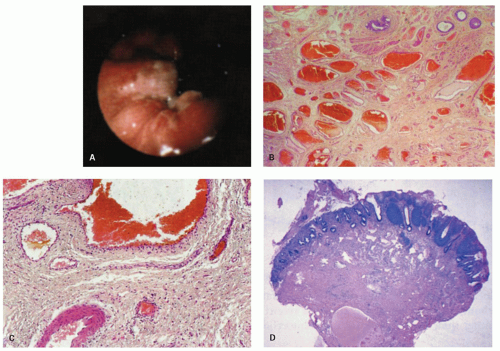

Small hemorrhoids cause virtually no problem. The most common manifestation is bleeding, manifested as streaks of blood on the outside of the stool. When hemorrhoids become larger, they may prolapse and fail to return following defecation, thereby drawing attention to themselves. Prolapsed hemorrhoids may produce a mucoid discharge, but pain is usually a feature only when they are acutely prolapsed, inflamed, thrombosed, or infarcted.19 Internal hemorrhoids can usually be distinguished from external hemorrhoids by the reddish rectal mucosa that covers the upper portion and the ATZ mucosa distally (Fig. 21-8).

A variety of surgical and nonsurgical techniques are used to treat hemorrhoids, including injection with sclerosants, banding, cryosurgery, electrocoagulation, and laser therapy.

Histologic Features

There is a surprising variability in the microscopic appearance of hemorrhoids. They are often less prominent immediately following resection because blood is lost from the numerous channels present, which collapse and are less impressive histologically than they would have been if distended. The dominant change is the presence of dilated vessels, mainly veins, of variable wall thickness in the submucosa. Other hemorrhoids consist primarily of numerous small vessels, along with fewer larger vessels (Fig. 21-8). Thrombosis and recanalization may be seen, and superficial ulceration may also be present. When colonic crypts are present, the lamina propria between them may be partially obliterated by fibromuscular tissue derived from but perpendicular to the muscularis mucosae. The fibromuscular proliferation is a reaction to local prolapse. In the adjacent tissue these may be marked neuronal hyperplasia, although the significance of this is unclear.20 The overlying epithelium may consist primarily of transitional or rectal mucosa in internal hemorrhoids or nonkeratinizing squamous pectinate mucosa and perianal skin in external ones. In addition, the epithelium may be acanthotic and keratinized, presumably in reaction to trauma. This may make the surface look white, that is, leukoplakia. One annoying surprise is the rare finding of squamous epithelial dysplasia.21 This will be dealt with later in the section of squamous carcinoma and its precursors.

Role of the Pathologist in Dealing with Hemorrhoidectomy Specimens

In general, hemorrhoids are sent to the pathologist because hospital regulations require that all excised tissue be sent. Some pathologists therefore document that tissue has been received but do not examine it microscopically. We routinely examine hemorrhoids to detect unsuspected lesions such as dysplasia or even invasive squamous carcinoma, although the yield is minute, and such examination may not be cost effective. On the rare occasions when we have found invasive squamous carcinoma, the surgeon admitted

that the appearance of the hemorrhoids was “not quite right” but was still surprised at the diagnosis.

that the appearance of the hemorrhoids was “not quite right” but was still surprised at the diagnosis.

Even if hemorrhoids are examined microscopically, there are virtually no data regarding the number and size of submucosal veins in the normal tissue for comparison with the abnormal tissue. Most samples with the typical dilated vessels are signed out simply as hemorrhoids. If thrombi or ulcers are present, they do not change the diagnosis. We do not mention if they are internal or external hemorrhoids, since that is a clinical decision, despite the fact that the mucosa covering them is different.

PERIANAL HEMATOMA (CLOTTED VENOUS SACCULE)

These hematomas are dark blue, tender lumps, usually between 2 and 4 cm in diameter, at the anal verge that are sometimes thought to be a variant of hemorrhoids. However, on the rare occasions when they are examined histologically, they seem to be a dilated venous channel or saccule, which contains recent blood clot, rather than the network seen in hemorrhoids.22

INFLAMMATORY LESIONS

Fissures and Fistulae

Minor degrees of acute and chronic inflammation are frequently present in the submucosa and around anal ducts. Some fibroepithelial polyps may be secondary to resolved fissures. Although the anatomy of fistulae is important surgically, and their anatomic origin and course are clinically important, specimens received for histologic examination usually consist of acute and chronic inflammatory cells, granulation tissue, sometimes abscesses, and fibrosis. The latter may also be present in the internal sphincter muscle away from the acute lesion, but not in controls, raising the question of a primary underlying lesion in the muscle.23 Mucosa or perianal skin may be present.

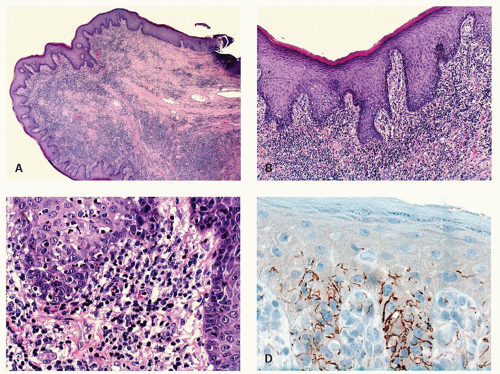

The major clinical question when the tissue from a fissure or fistula is seen is whether, in a patient without known underlying Crohn’s disease, the fissure or fistula may be the anal or perianal component of Crohn’s disease (see the chapter on Crohn’s disease). In these tissues, occasional foreign body giant cells or even rare small granulomas are found, resulting from a reaction to contents of the bowel or sometimes to substances that have been applied topically. These should not be interpreted as Crohn’s disease. If more substantial granulomas are found, then Crohn’s disease or even infections become possibilities, and the clinicians should be told. Even more suggestive of Crohn’s disease are numerous lymphoid aggregates similar to those in the transmural inflammation in other parts of the bowel, especially if accompanied by granulomas (Fig. 21-10). Like Crohn’s disease, tuberculosis affects the anus and perianal skin. As with all anal specimens, the overlying mucosa should be examined for the presence of condylomas and dysplasia.21

The major clinical question when the tissue from a fissure or fistula is seen is whether, in a patient without known underlying Crohn’s disease, the fissure or fistula may be the anal or perianal component of Crohn’s disease (see the chapter on Crohn’s disease). In these tissues, occasional foreign body giant cells or even rare small granulomas are found, resulting from a reaction to contents of the bowel or sometimes to substances that have been applied topically. These should not be interpreted as Crohn’s disease. If more substantial granulomas are found, then Crohn’s disease or even infections become possibilities, and the clinicians should be told. Even more suggestive of Crohn’s disease are numerous lymphoid aggregates similar to those in the transmural inflammation in other parts of the bowel, especially if accompanied by granulomas (Fig. 21-10). Like Crohn’s disease, tuberculosis affects the anus and perianal skin. As with all anal specimens, the overlying mucosa should be examined for the presence of condylomas and dysplasia.21

Infections

The anus is subject to a variety of infections, some of which occur simultaneously with rectal involvement. The most common anal infections are discussed below. Refer to more detailed discussion on GI infections in Chapter 19.

Viral infections—herpes and papillomavirus. Anal and perianal herpes virus infection occurs, but it is usually part of more extensive rectal involvement. The lesions involving the pecten and perianal skin are identical to those in other squamous surfaces, with the typical nuclear inclusions in squamous cells. Human papilloma virus infection is the most important anal and perianal infection because of its association with anal carcinomas. This is discussed subsequently.

Syphilis. Primary chancres are usually suspected clinically, and it is only if the presentation is atypical, such as a fissure, that the lesion is likely to be biopsied. The diffuse plasma cell infiltrate, particularly in association with endarteritis, should alert the pathologist to the diagnosis. If there is a high level of clinical suspicion, this diagnosis should be considered. Appropriate silver or immuno stain should be carried out. However zoon can produce a similar dense plasmacytic infiltrate.

Condylomata lata, the proliferative lesion, can also occur in the anal region as a manifestation of secondary syphilis. The lesions have no specific features but can mimic a variety of other dermatological conditions or look like inflamed skin tags. The inflammatory infiltrate can be a mixture of all types of chronic inflammatory cells including immunoblasts that may lead to a consideration of lymphoma (see lesion in gastritis Chapter 13), and plasma cells may or may not predominate. While the endothelium may be prominent it is usually no more so than in many other inflammatory lesions. The overlying epithelium is usually hyperplastic, spongiotic, and has focal neutrophils (Fig. 21-9). The diagnosis usually take a high degree of clinical suspicion as all tissue examined from inflammatory anal lesions other than overt abscesses are

potentially good starters for syphilis, but it is obviously impractical to screen them all. Unless really “on the ball,” something other than the morphological appearances usually has to trigger the search for the myriad organisms present. On immunostains organisms predominate in the basal zone of the squamous epithelium, usually in the spongiotic intercellular space (Fig. 21-9D). They are less frequent in the lamina propria, and uncommon in the deep inflammatory infiltrate, but when present do tend to be around endothelium.

potentially good starters for syphilis, but it is obviously impractical to screen them all. Unless really “on the ball,” something other than the morphological appearances usually has to trigger the search for the myriad organisms present. On immunostains organisms predominate in the basal zone of the squamous epithelium, usually in the spongiotic intercellular space (Fig. 21-9D). They are less frequent in the lamina propria, and uncommon in the deep inflammatory infiltrate, but when present do tend to be around endothelium.

Lymphogranuloma venereum. This disease caused by the bacterium, Chlamydia trachomatis, is another disease in which the histologic findings are nonspecific, consisting primarily of granulation tissue with lymphoid aggregates. Conversely in cases with rectal lymphoid hyperplasia (rectal tonsil) a possibility of Chlamydia infection should be considered in the differential diagnosis. In the later stages, the resultant scar may cause severe strictures.24

Granuloma inguinale. This disease frequently presents with perianal ulcers. The biopsy findings display a heavy plasma cell and neutrophil infiltrate. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia may be present. The characteristic Leishman-Donovan bodies may be found in macrophages and are best identified using either Warthin-Starry or Giemsa stain. The causative organism is the bacterium Calymmatobacterium granulomatis.

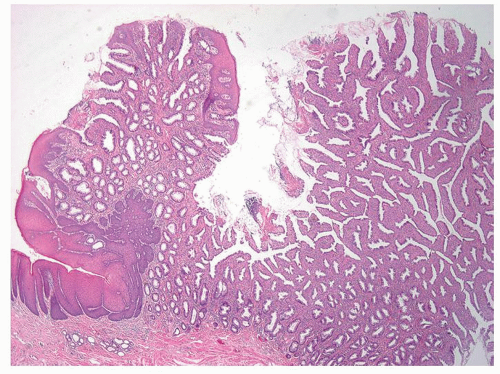

PROLAPSE AND INFLAMMATORY CLOACOGENIC POLYPS

The changes of prolapse, seen best in the distal rectum, are a mixture of hypertrophy and hyperplasia of muscle extending perpendicularly toward or into the mucosa from the muscularis mucosae; profound architectural distortion with strangely shaped crypts and often surface villiform change; and superficial ulcers, commonly on the tips of these strange villi (Fig. 21-11). The lamina propria is commonly full of collagen, smooth muscle, and many capillaries, and it is likely to contain fewer than the normal number of inflammatory cells, mainly plasma cells. In some cases, there is downgrowth of

crypts into the submucosa, a change known as “colitis cystica profunda.” Sometimes all the changes are present, while other times one or two of the changes dominate. These anatomic changes are really the result of trauma, which may be secondary to several physiologic alterations, including abnormal muscle contraction as in the solitary rectal ulcer syndrome, or protrusions into the including polyps and hemorrhoids. Occasionally prolapse at the anorectal junction results in peculiar polyps that cross that junction. In this location, they have been called inflammatory cloacogenic polyps,25 they tend to present in middle-aged and older individuals as hemorrhoids, often with bleeding, and there may be a female preponderance. A few cases have been reported to be associated with the solitary rectal ulcer syndrome.26 The name is actually inappropriate. They are not inflammatory lesions but prolapse presumably due to trauma, and they are not in the place where the embryonic cloacal membrane was situated.

crypts into the submucosa, a change known as “colitis cystica profunda.” Sometimes all the changes are present, while other times one or two of the changes dominate. These anatomic changes are really the result of trauma, which may be secondary to several physiologic alterations, including abnormal muscle contraction as in the solitary rectal ulcer syndrome, or protrusions into the including polyps and hemorrhoids. Occasionally prolapse at the anorectal junction results in peculiar polyps that cross that junction. In this location, they have been called inflammatory cloacogenic polyps,25 they tend to present in middle-aged and older individuals as hemorrhoids, often with bleeding, and there may be a female preponderance. A few cases have been reported to be associated with the solitary rectal ulcer syndrome.26 The name is actually inappropriate. They are not inflammatory lesions but prolapse presumably due to trauma, and they are not in the place where the embryonic cloacal membrane was situated.

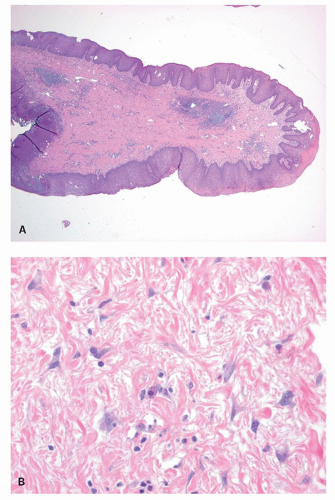

ANAL TAGS (FIBROEPITHELIAL POLYPS)

These lesions are commonly resected because they look like hemorrhoids clinically. They are identical to skin tags or acrochordons elsewhere. They contain a core of fibrous or fibrovascular tissue covered by stratified squamous epithelium, which is commonly nonkeratinized, but which may be keratinized, especially if the tag is chronically irritated (Fig 21-12). In one study, it was found that multinucleated stromal cells, actually peculiar fibroblasts and myofibroblasts, are common in these tags, but they are also common in the flat anal stroma.27, 28 The authors of this study suggested that anal tags are actually reactive hyperplasias of the subepithelial connective tissue of the anal mucosa. Some of these tags occur at the opening of sinuses or fistulae.

TUMORS OF THE ANUS

The most common masses, lumps, and bumps of the anal region are nonneoplastic lesions, mostly hemorrhoids, tags, condylomas, and lumpy inflammations, some of which are associated with fistulae. Primary neoplasms of this region are uncommon. As a result of this, the rare anal neoplasms are likely to have the same presenting symptoms as do the very common benign diseases. This may account for the fact that anal cancers

tend to present in advanced stages. If an individual has an anal lump or some minor bleeding, that individual and probably that individual’s physician are much more likely to think it is something benign, like a hemorrhoid, than a carcinoma. Anal cancers are likely to present in middle-aged patients, a similar patient population for cancers in most of the rest of the GI tract. In some large centers, secondary tumors, particularly lymphoid and hematopoietic proliferation in the terminal stages of the disease, may occur on rare occasions. The usual variants of squamous carcinoma make up about 95% of all anal canal tumors. The remainder are really rare and include adenocarcinomas and melanomas.

tend to present in advanced stages. If an individual has an anal lump or some minor bleeding, that individual and probably that individual’s physician are much more likely to think it is something benign, like a hemorrhoid, than a carcinoma. Anal cancers are likely to present in middle-aged patients, a similar patient population for cancers in most of the rest of the GI tract. In some large centers, secondary tumors, particularly lymphoid and hematopoietic proliferation in the terminal stages of the disease, may occur on rare occasions. The usual variants of squamous carcinoma make up about 95% of all anal canal tumors. The remainder are really rare and include adenocarcinomas and melanomas.

Epithelial Hyperplasia Without Dysplasia (Pseudoepitheliomatous Hyperplasia)

Squamous epithelial hyperplasia, also known as acanthosis, is analogous to similar lesions occurring elsewhere, particularly in the oral mucosa. It may be found in the epithelium covering hemorrhoids as a reactive change, usually in the ATZ, possibly due to prolapse, but it may also be an upgrowth of the pecten over the transition zone following ulcers (Fig. 21-13). Thick isolated plaques of squamous hyperplasia occur in the midst of chronic inflammation. Some of these are so proliferative that they look invasive at their bases, making the low-power distinction from an unusually well-differentiated squamous carcinoma nearly impossible. However, the basal layer lacks the atypia associated with squamous carcinomas, supporting the notion that these are reactive and pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. Unfortunately, there is virtually no literature on these lesions, so we have no clue as to their behavior and etiology. A few cases may have been reported as keratoacanthomas, but they lack the central keratin-filled cup.

On occasions, reactive acanthosis is keratinized, so that it looks white, much like comparable lesions in the perianal skin, where the squamous hyperplasias commonly is covered by a thick layer of hyperkeratosis, which results in a clinically visible thick, whitish plaque, sometimes well circumscribed, that is referred to as leukoplakia. However, even dysplasia can be hyperkeratotic and look like any other white plaque or leukoplakia.

Condyloma Acuminatum

These squamous proliferations are venereally transmitted human papillomavirus (HPV) infections. Many are warty or papillary growths that are soft and have a predilection for moist surfaces, such as the genitalia and perineum, as well as the anal canal and perianal skin. Others are flat or plaque-like lesions, and are more likely to be found in the anal mucosa. They are mostly small lesions. The largest lesions are discussed below as giant condylomas, now known as verrucous carcinomas. Multiple lesions are common (Fig. 21-14).

HPV types 6 and 11 are by far the most common types in simple condyloma, but oncogenic types, especially 16 and 18 can also be detected but less frequently.29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40

HPV types 6 and 11 are by far the most common types in simple condyloma, but oncogenic types, especially 16 and 18 can also be detected but less frequently.29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree