|

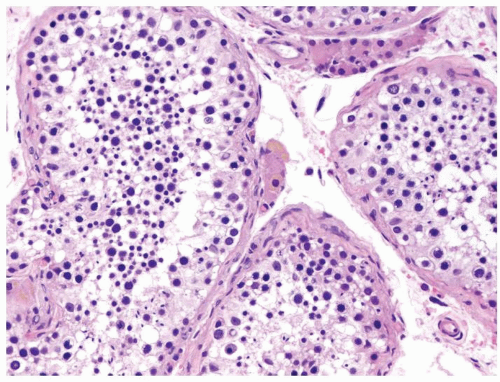

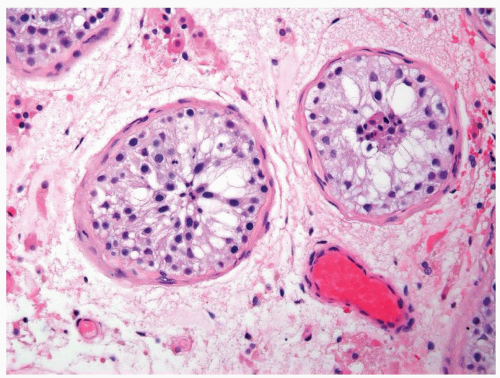

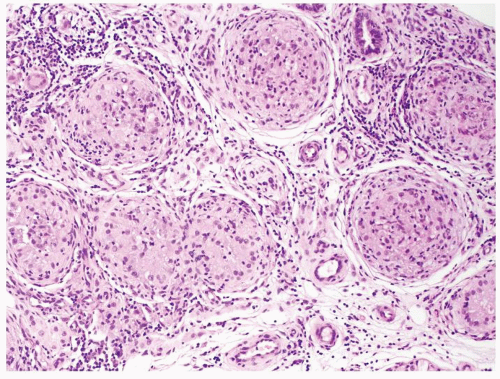

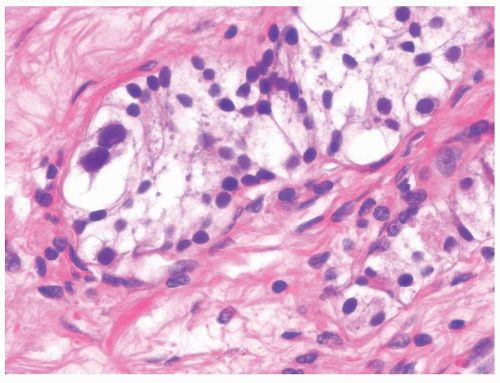

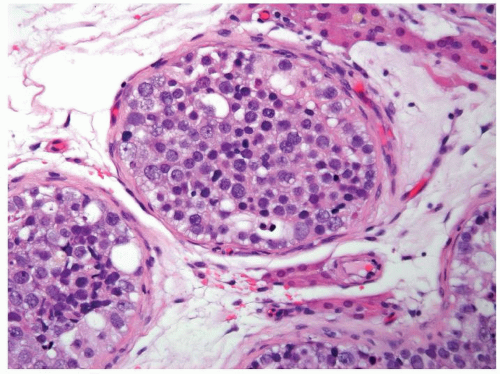

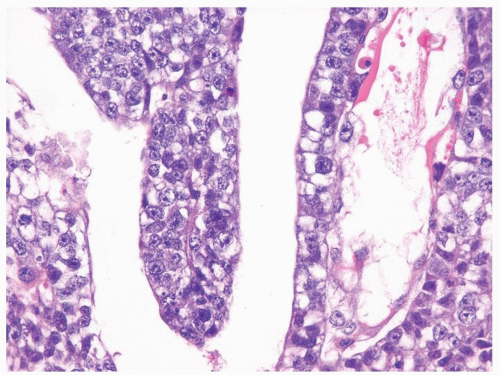

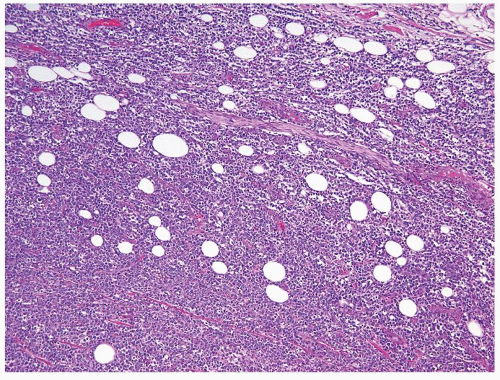

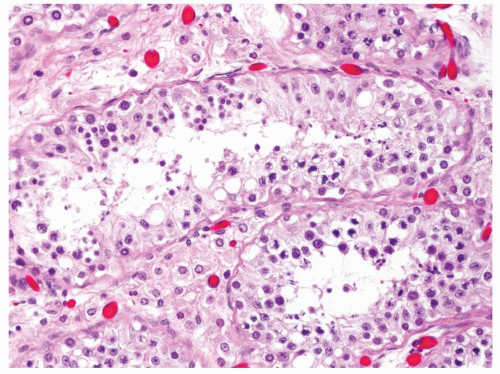

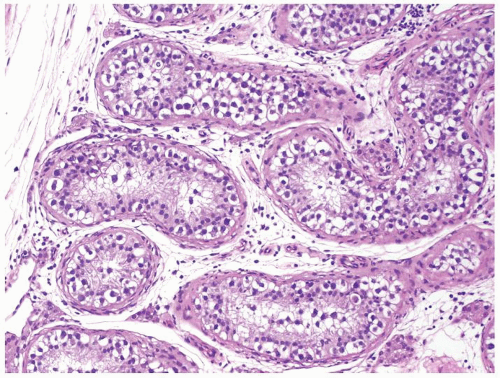

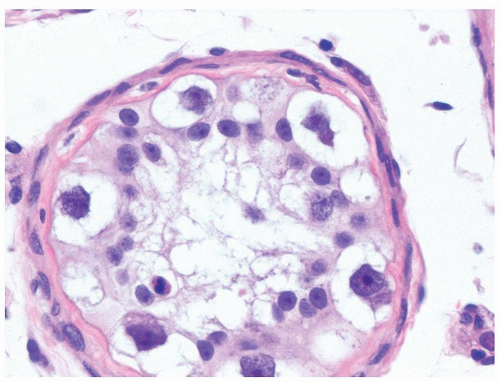

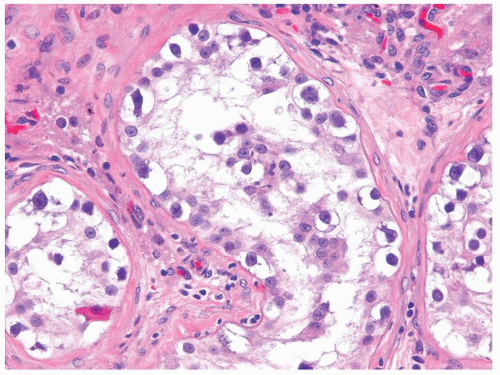

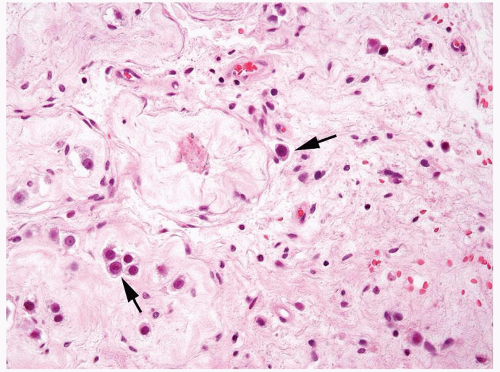

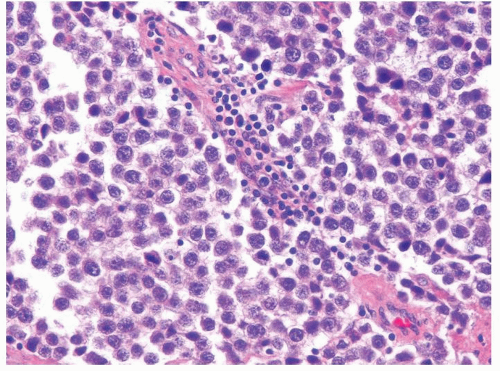

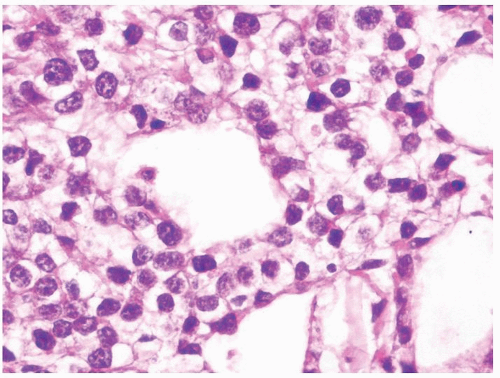

Figure 4.1.4 Adult seminiferous tubules with hypospermatogenesis. The overall total number of germ cells is decreased. |

|

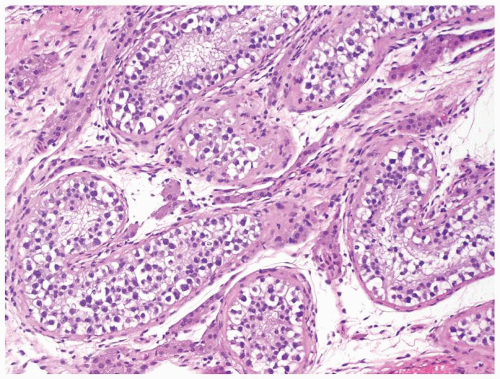

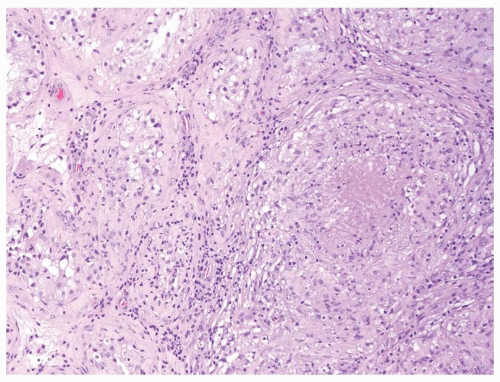

Figure 4.2.1 Adult seminiferous tubules with hypospermatogenesis. Full maturation through all spermatogenic stages occur, but the overall total number of germ cells is decreased. |

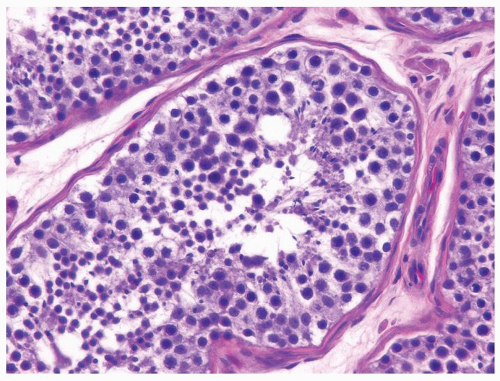

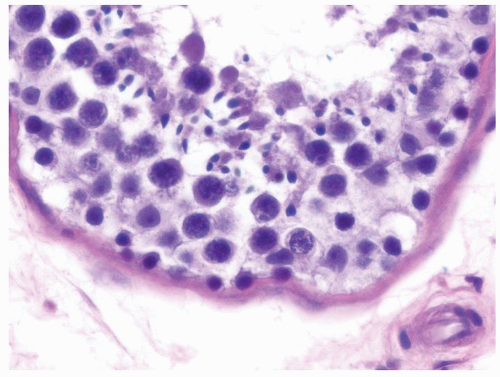

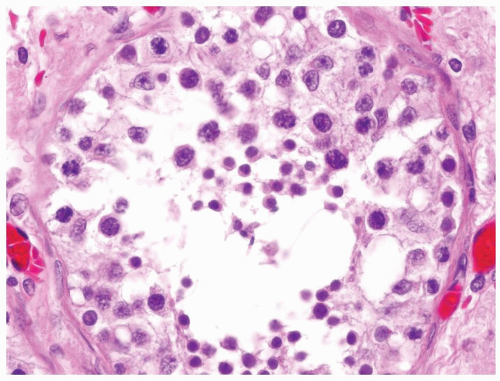

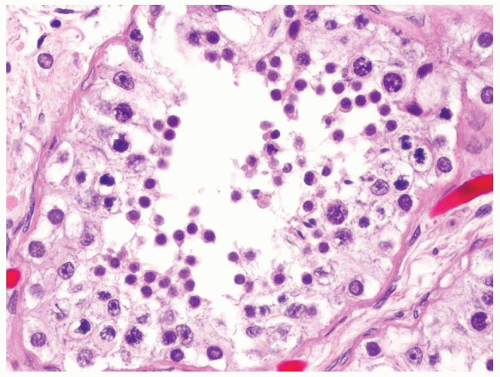

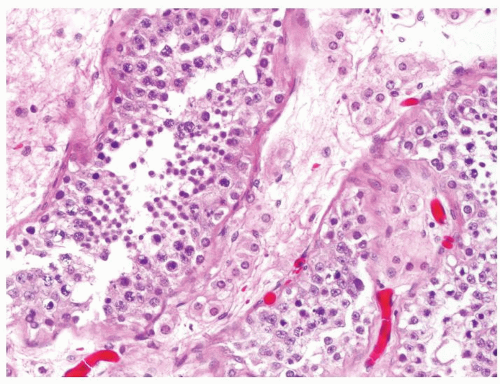

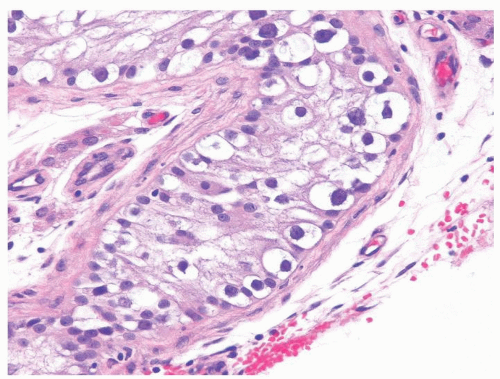

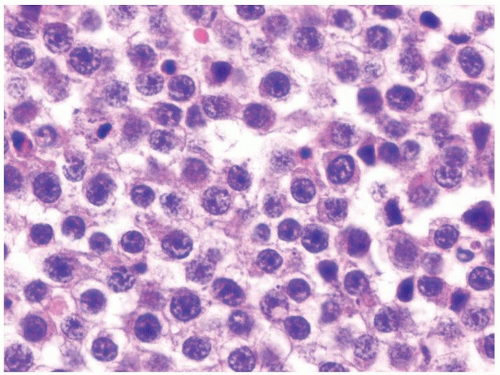

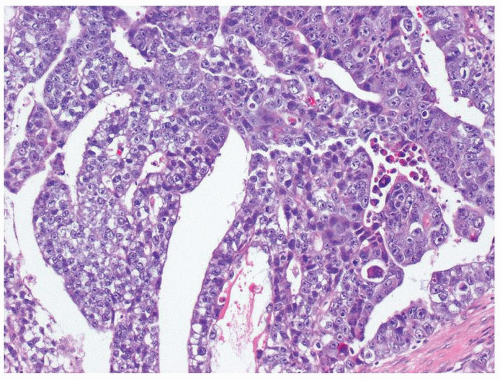

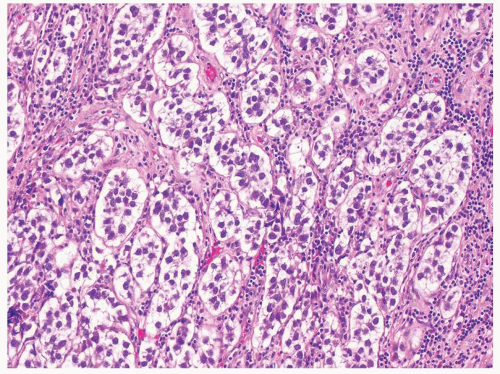

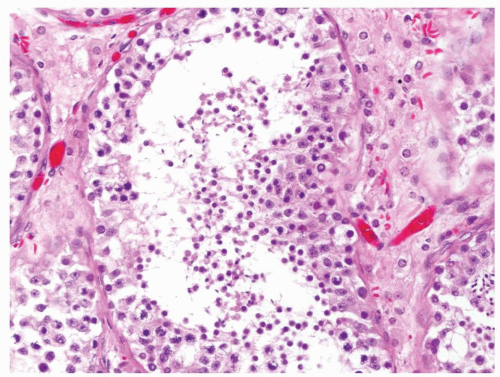

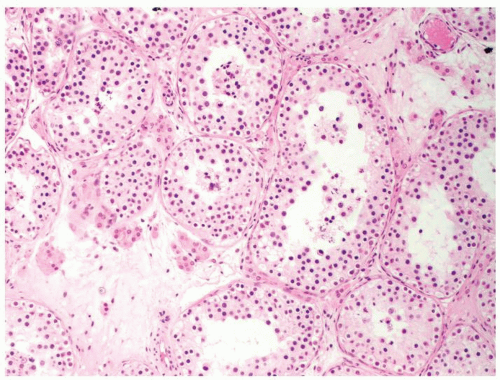

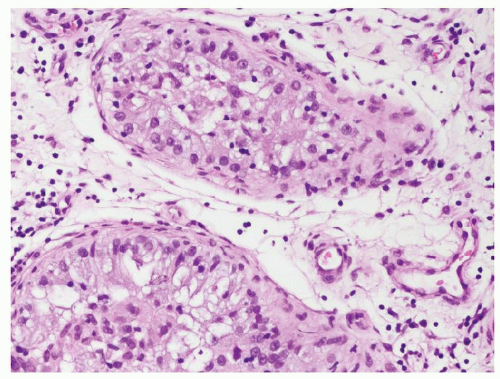

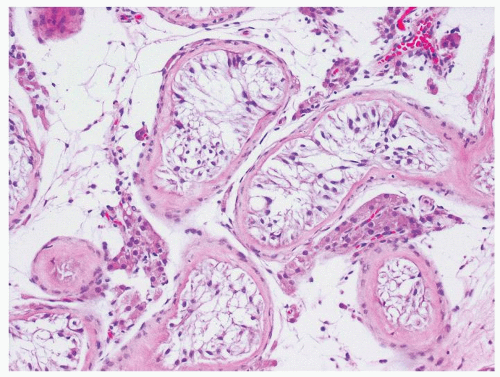

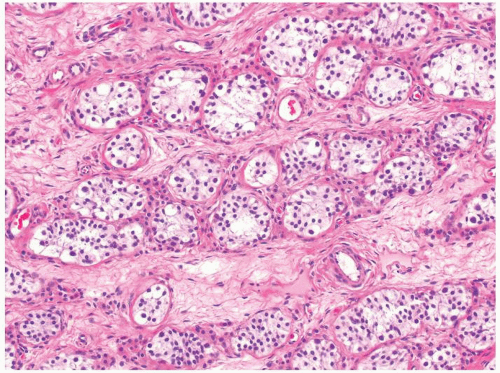

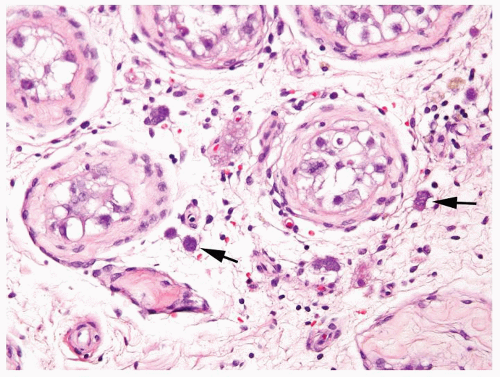

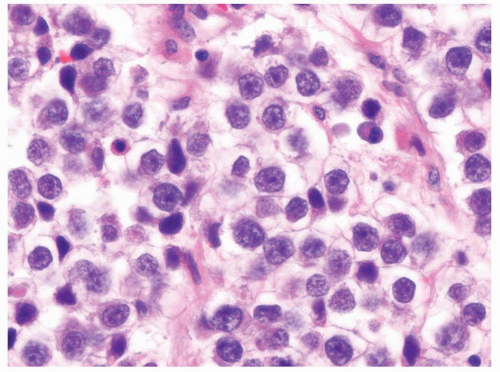

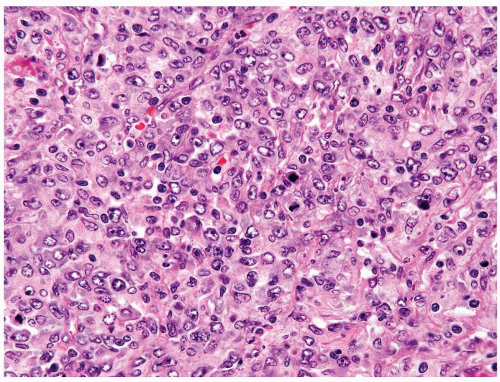

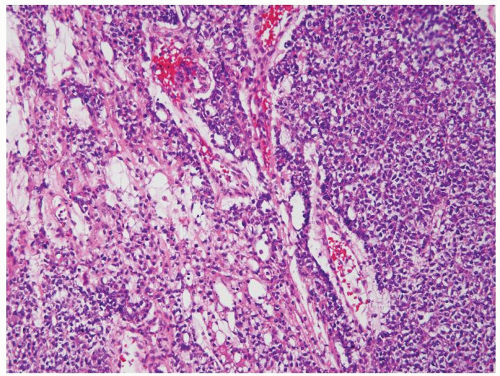

Figure 4.2.4 Adult seminiferous tubules showing maturation arrest at the secondary spermatocyte phase. Note absence of spermatid and spermatozoa. |

Figure 4.2.5 Adult seminiferous tubules showing maturation arrest at the secondary spermatocyte phase. |

|

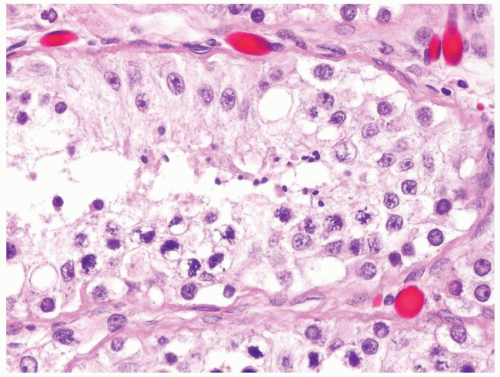

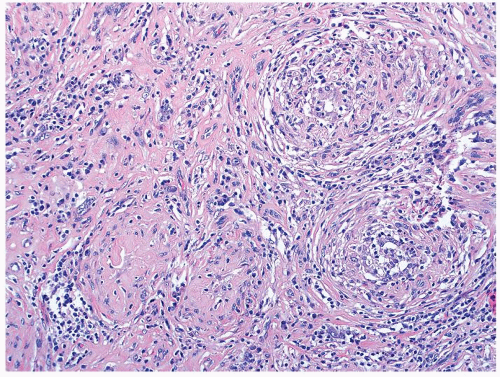

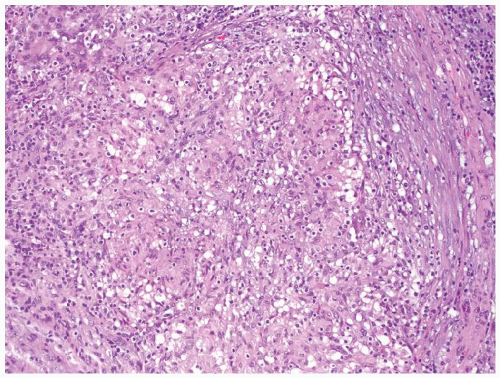

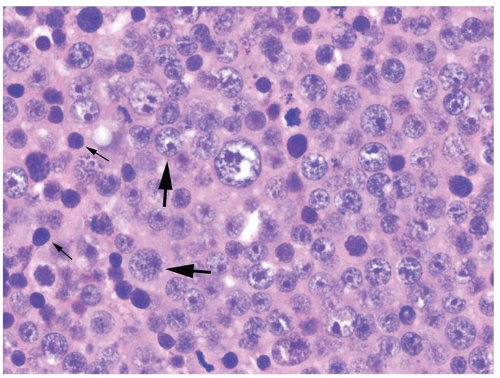

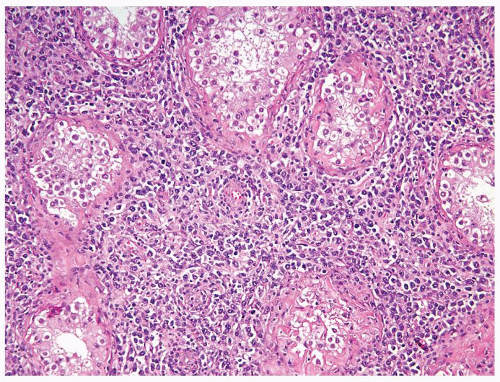

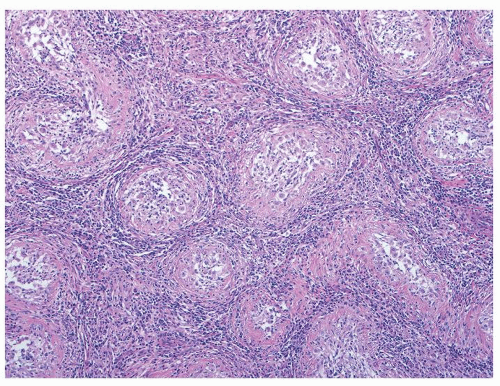

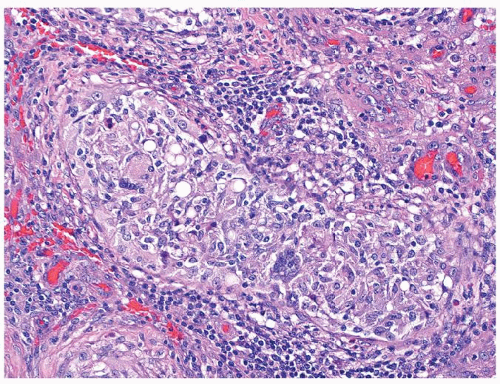

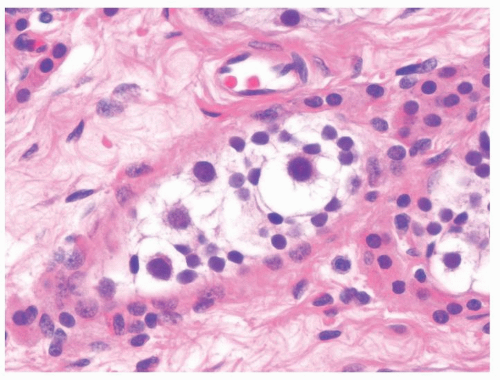

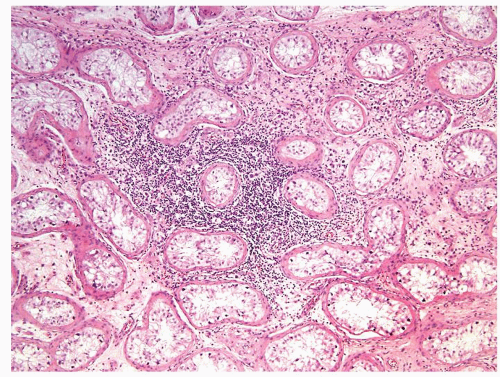

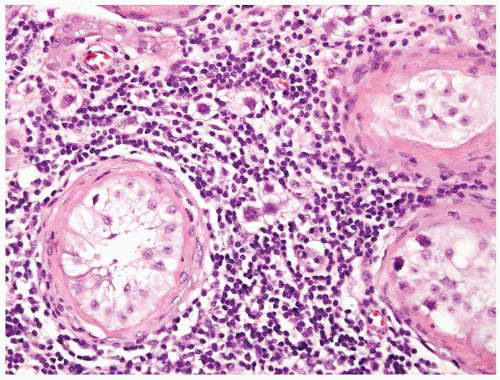

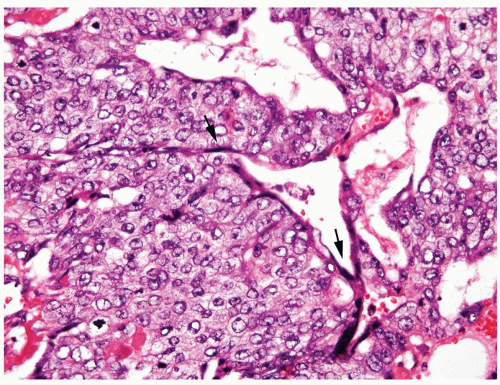

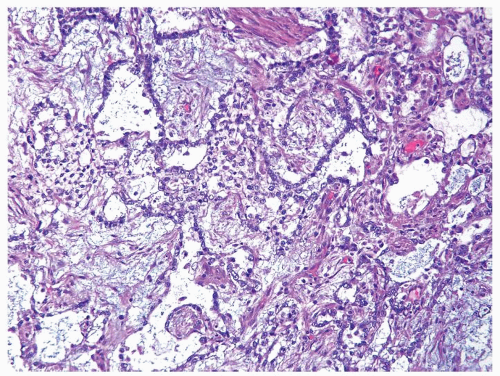

Figure 4.3.2 Idiopathic granulomatous orchitis. Granulomas are composed of epithelioid histiocytes and giant cells. |

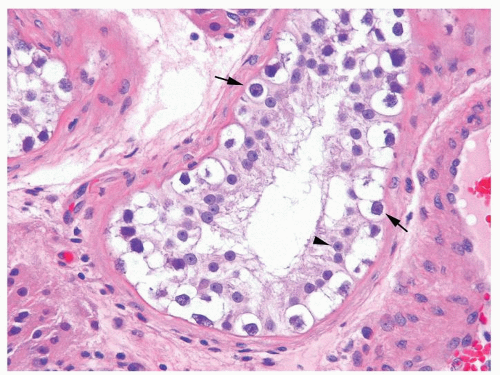

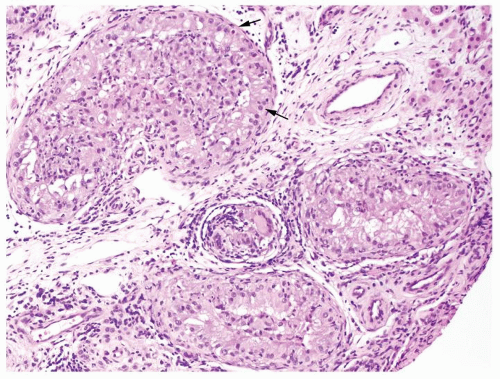

Figure 4.3.3 Idiopathic granulomatous orchitis showing nonnecrotizing granulomas filling seminiferous tubules. Residual germ cells are noted (arrows). |

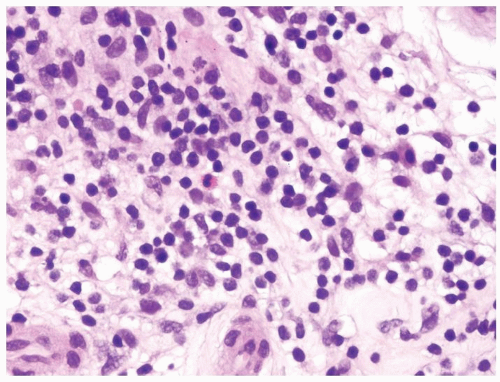

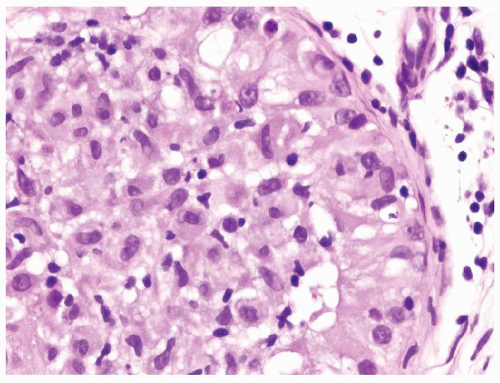

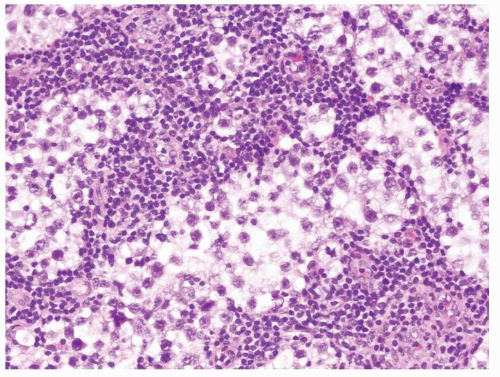

Figure 4.3.4 Idiopathic granulomatous orchitis. Associated chronic inflammation is illustrated with occasional eosinophils admixed with lymphocytes and plasma cells. |

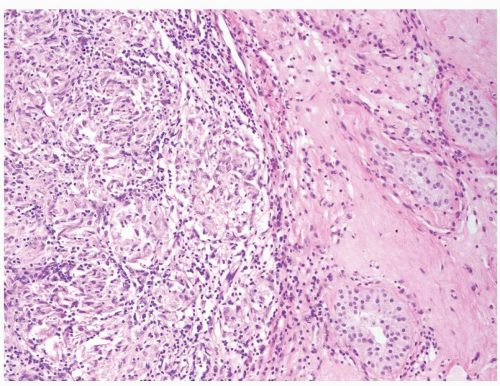

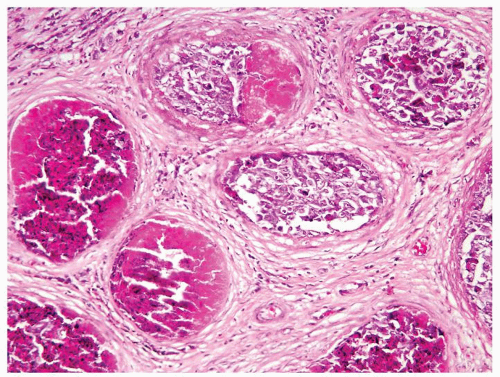

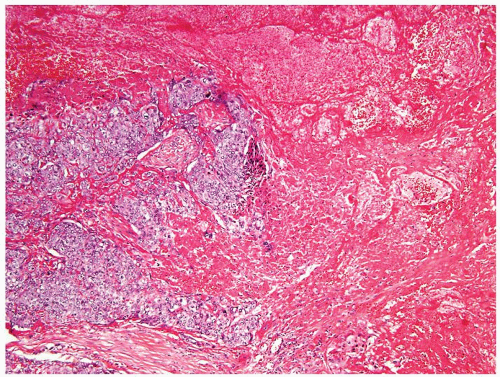

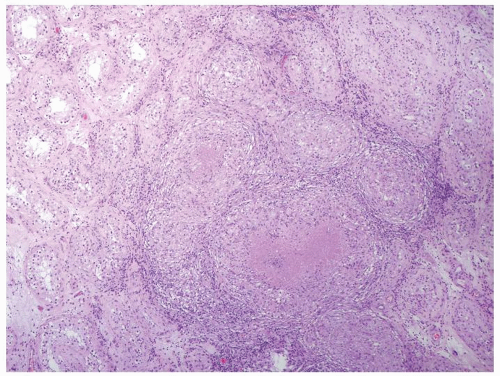

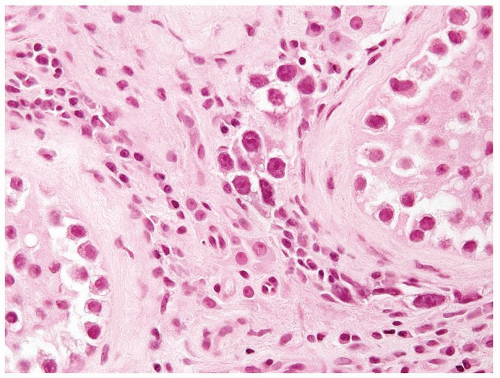

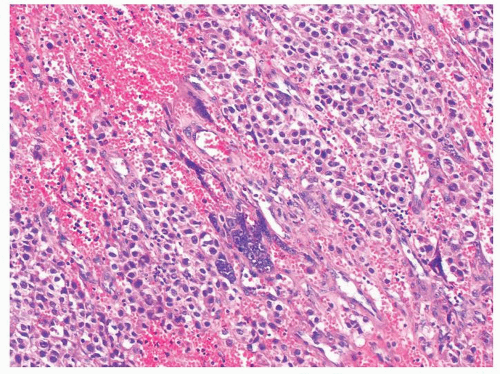

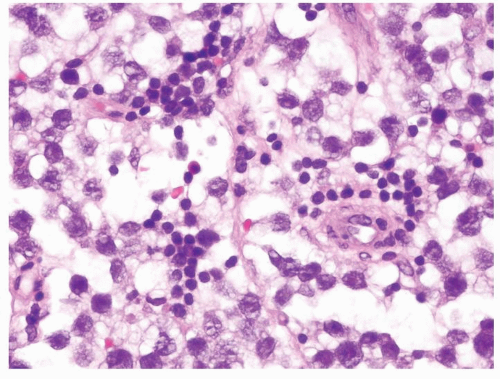

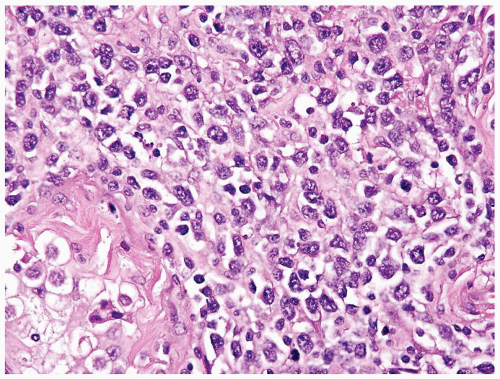

Figure 4.3.6 Mycobacterial granulomatous orchitis. Necrotizing granulomas with palisaded central necrosis is illustrated. |

Figure 4.3.7 Mycobacterial granulomatous orchitis. Necrotizing granulomas involve the interstitium with minimal involvement of atrophic seminiferous tubules seen on the left side. |

|

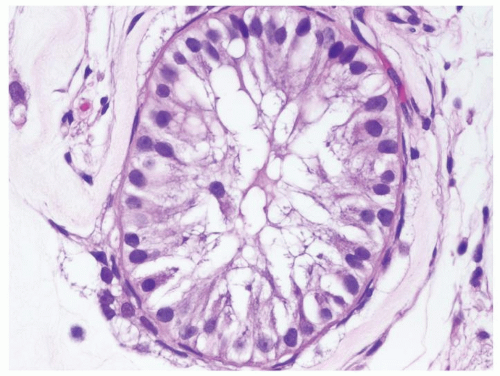

Figure 4.4.1 Idiopathic granulomatous orchitis showing nonnecrotizing granulomas filling seminiferous tubules. Note lack of cytologic atypia in Sertoli cells at periphery of the tubules. |

Figure 4.4.2 Idiopathic granulomatous orchitis with a seminiferous tubule filled with epithelioid histiocytes. There is a lack of atypical cells. |

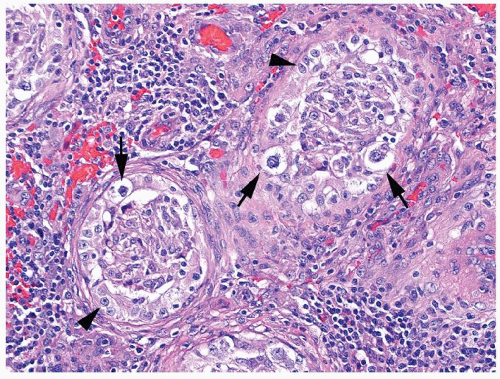

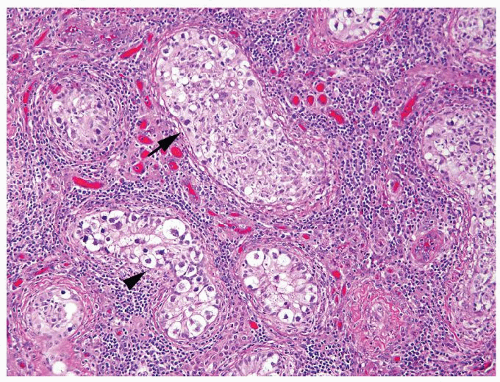

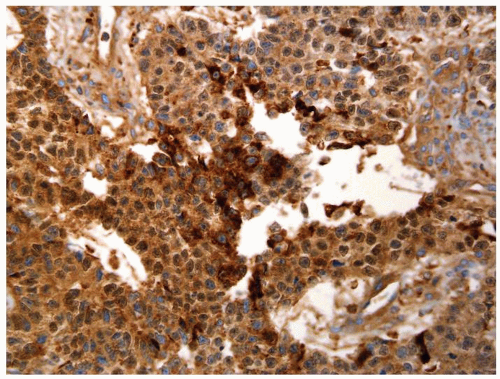

Figure 4.4.3 Some seminiferous tubules with IGCNU not involved with granulomatous response (arrowhead). Other tubules have granulomatous inflammation within the tubules involved by IGCNU (arrow). |

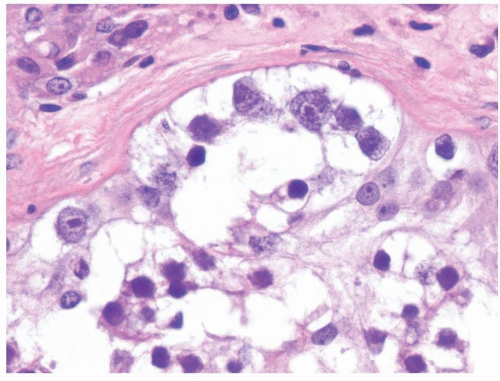

Figure 4.4.5 Nonnecrotizing granulomas in association with IGCNU (same case as in Figure 4.4.4) with extensive intratubular granulomatous reaction destroying IGCNU cells, mimicking idiopathic granulomatous orchitis. |

|

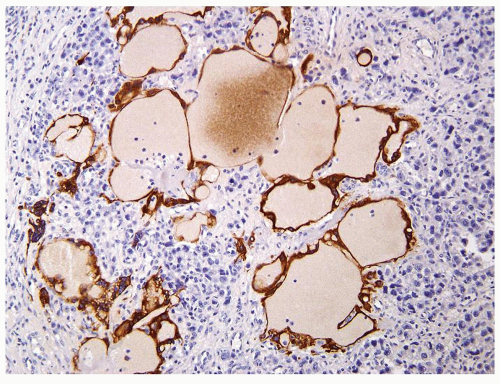

Figure 4.5.1 Focal nonnecrotizing interstitial granulomatous inflammation composed of histiocytes is seen in septae dividing sheets of seminoma cells. |

Figure 4.5.5 Nonnecrotizing granulomatous orchitis in sarcoidosis composed of well-formed granulomas. Note surrounding scarring and atrophic seminiferous tubules lacking IGCNU. |

|

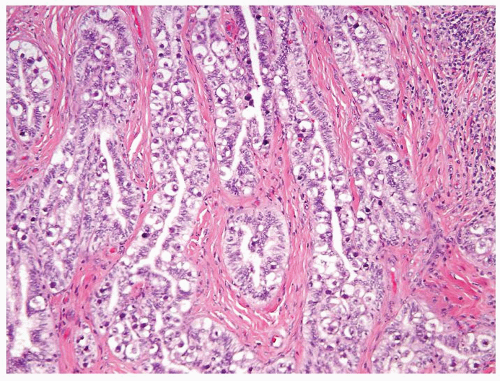

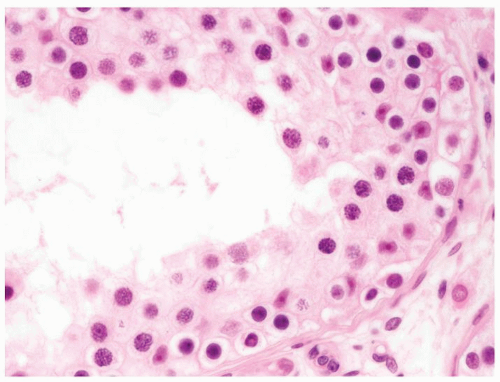

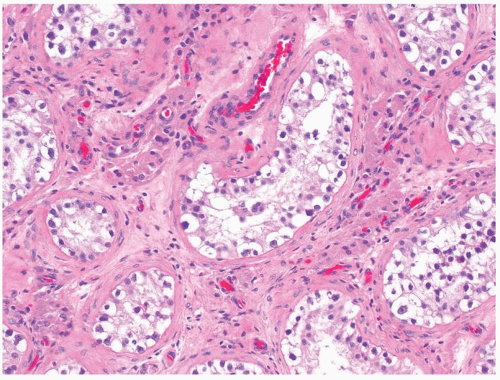

Figure 4.6.1 Seminiferous tubules contain IGCNU. Enlarged, atypical germ cells with cytoplasmic clearing in a single row along a thickened basement membrane are noted. |

Figure 4.6.3 IGCNU cells have clear cytoplasm, irregular nuclear contours, coarse chromatin, and enlarged single or multiple enlarged variably sized nucleoli. |

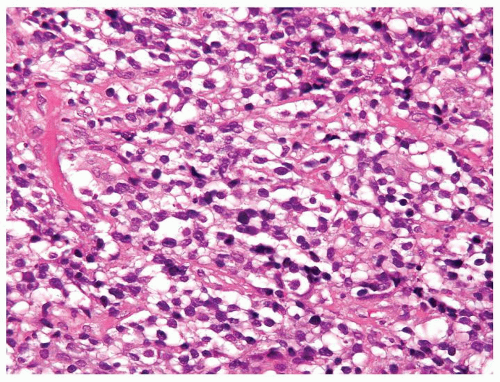

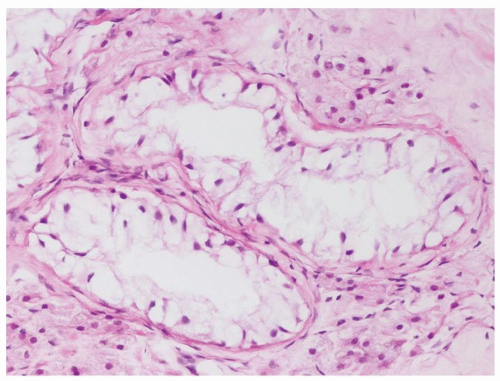

Figure 4.6.4 Seminiferous tubules contain only Sertoli cells. Cells at low power often have a wispy appearance. Peritubular fibrosis is common. |

Figure 4.6.5 Seminiferous tubules contain only Sertoli cells with small bland nuclei and abundant vacuolated cytoplasm. |

|

Figure 4.7.1 Seminiferous tubules contain IGCNU. Enlarged, atypical germ cells are situated as a single row along a thickened basement membrane. |

Figure 4.7.2 IGCNU cells have clear cytoplasm, irregular nuclear contours, coarse chromatin, and enlarged single or multiple enlarged variably sized nucleoli. |

Figure 4.7.4 Spermatogonia with clear cytoplasm containing small-size nuclei with round and regular nuclear contours are seen in this prepubertal testis. |

Figure 4.7.5 Occasional spermatogonia in the prepubertal testes may increase in size but maintain regular nuclear contour. The lack of atypia distinguishes these giant spermatogonia from IGCNU. |

|

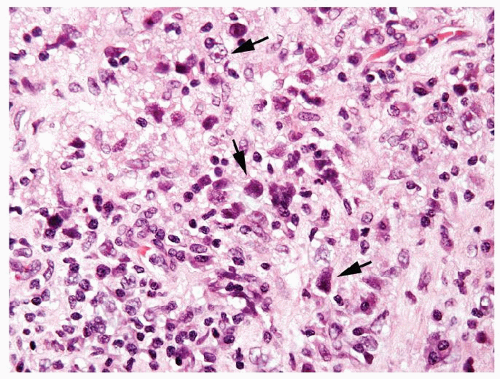

Figure 4.8.2 Intertubular/interstitial invasive seminoma component adjacent to the seminiferous tubule with IGCNU. |

Figure 4.8.3 Intertubular/interstitial invasive seminoma (arrows) adjacent to sclerotic seminiferous tubules. |

Figure 4.8.4 Intertubular/interstitial invasive seminoma (arrows) permeating the testicular stroma between the seminiferous tubule with IGCNU. |

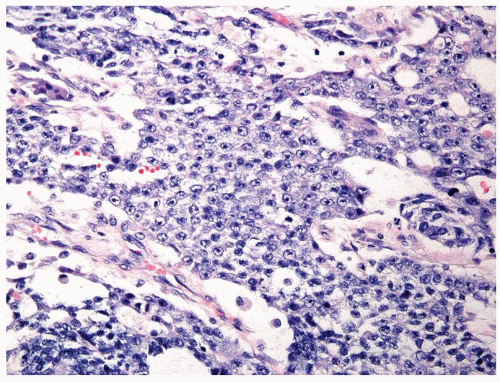

Figure 4.8.5 Associated lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate is a clue raising the suspicion for the presence of an invasive component. |

Figure 4.8.6 Same case as Figure 4.8.5 with intertubular invasive neoplastic seminoma cells in lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate. |

|

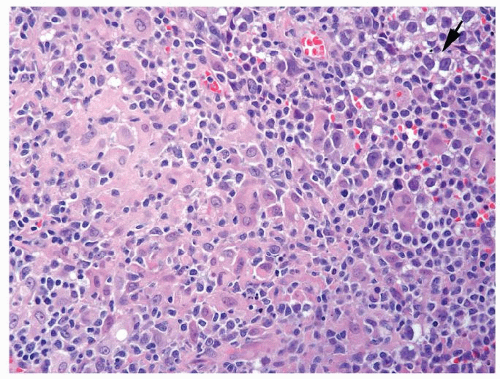

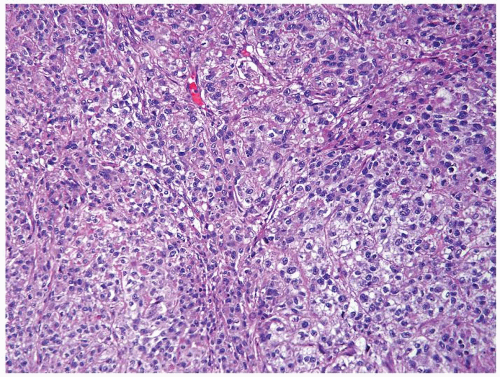

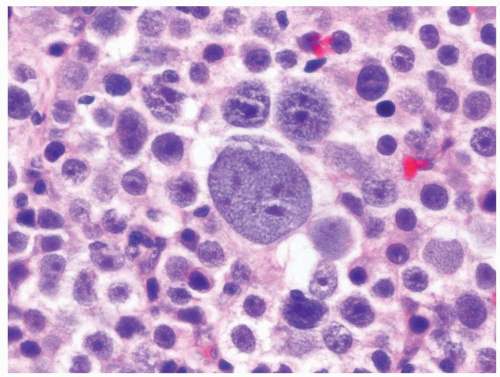

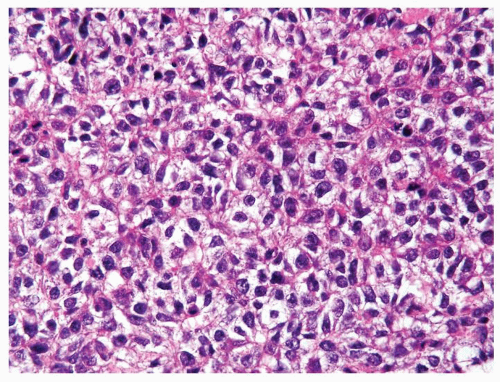

Figure 4.9.1 Classic seminoma composed of monotonous round-to-polygonal cleared cells with ovoid nuclei containing one or more prominent nucleoli with scattered interstitial lymphocytic infiltrate. |

Figure 4.9.2 Monotonous round-to-polygonal cleared cells with ovoid nuclei typical of classic seminoma. |

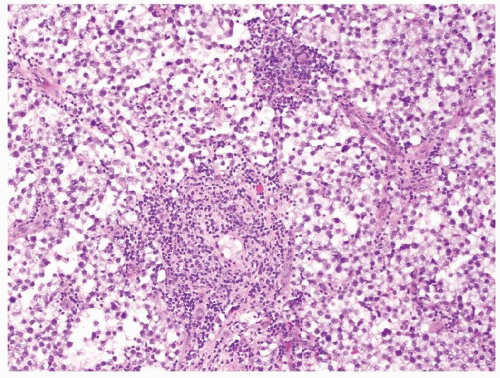

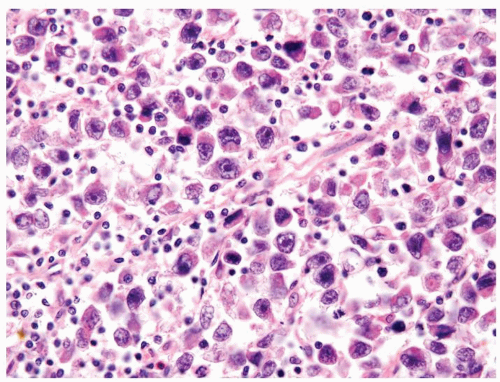

Figure 4.9.5 Spermatocytic seminoma is composed of three basic cell types. Lymphocytic host response is lacking. |

|

Figure 4.10.1 Classic seminoma is composed of loosely cohesive monotonous round-to-polygonal cells with clear cytoplasm. |

Figure 4.10.3 Seminoma with greater than usual pleomorphism. Cells are still loosely cohesive with interspersed lymphocytes. |

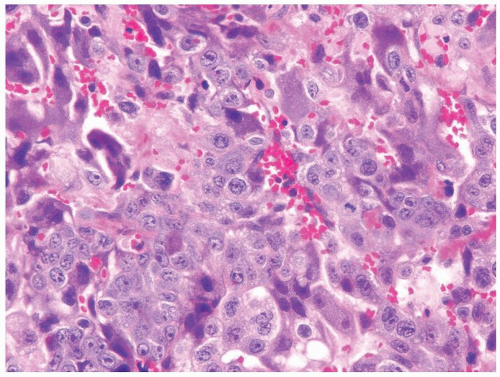

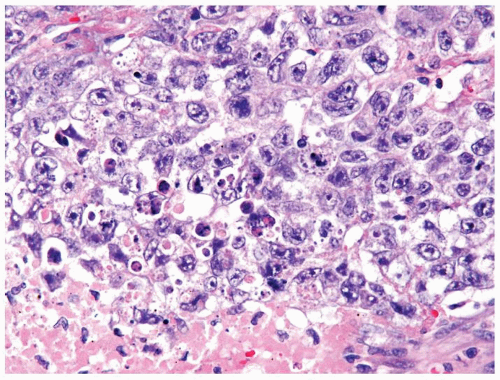

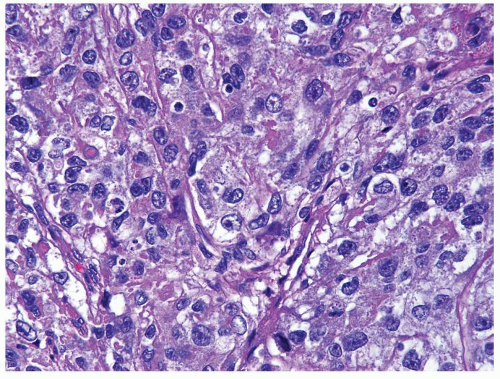

Figure 4.10.6 Embryonal carcinoma composed of large polygonal cells with abundant granular amphophilic cytoplasm and large vesicular irregular nuclei with one or more irregular nucleoli. |

Figure 4.10.9 Unusual embryonal carcinoma with lymphocytic infiltrate. Cells are cohesive with clefts. |

|

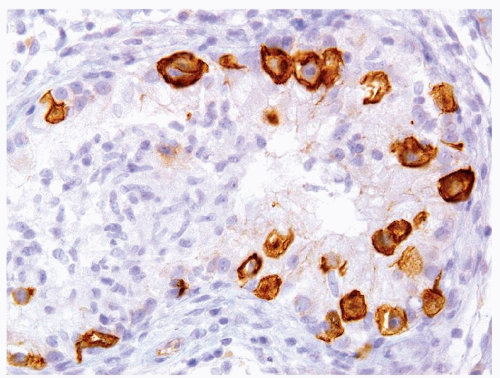

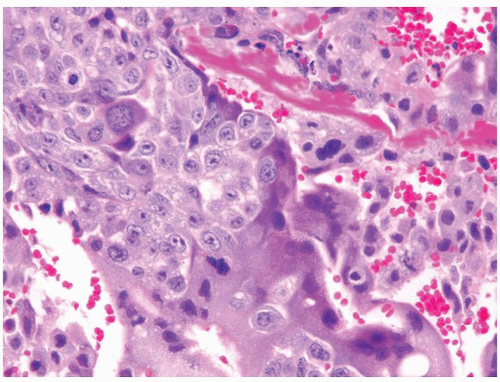

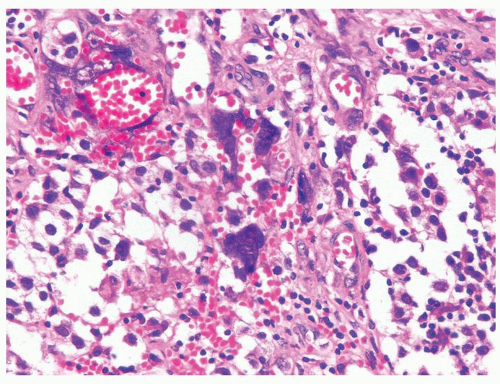

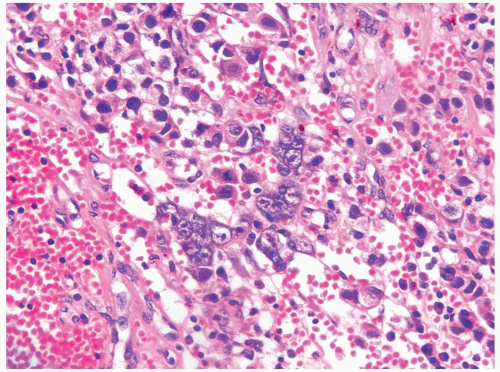

Figure 4.11.1 Seminoma admixed with syncytiotrophoblasts, which are multinucleated cells that contain abundant basophilic cytoplasm. No cytotrophoblasts are accompanied. |

Figure 4.11.2 Syncytiotrophoblasts without associated cytotrophoblasts are seen adjacent to areas of hemorrhage in seminoma. |

Figure 4.11.3 Syncytiotrophoblasts without associated cytotrophoblasts are seen surrounding vascular structures in seminoma. |

Figure 4.11.4 Syncytiotrophoblasts without associated cytotrophoblasts are seen adjacent to areas of hemorrhage in seminoma. |

Figure 4.11.5 Syncytiotrophoblasts without associated cytotrophoblasts are seen surrounding vascular structures in seminoma. |

Figure 4.11.6 Same case as in Figure 4.11.5 with highlighting of syncytiotrophoblasts by HCG immunostains. |

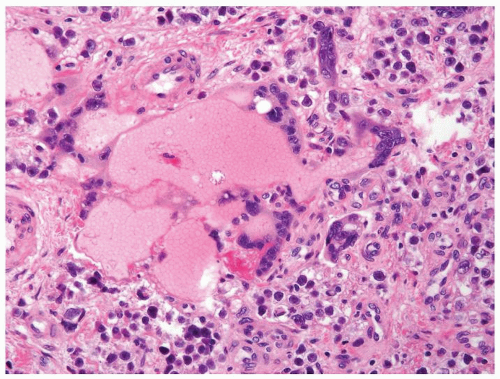

Figure 4.11.9 Choriocarcinoma with subtle syncytiotrophoblasts (arrows) enveloping cytotrophoblasts. |

|

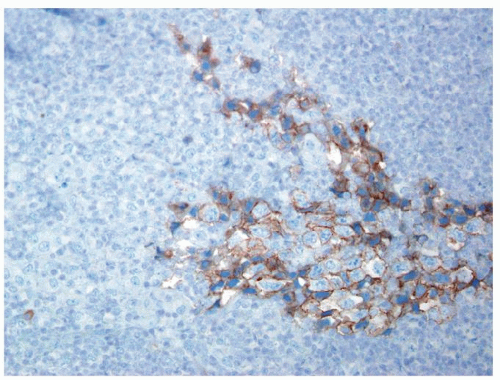

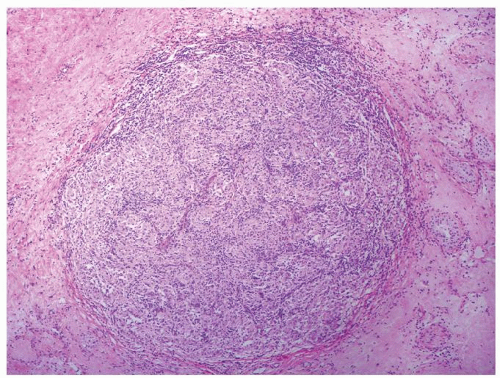

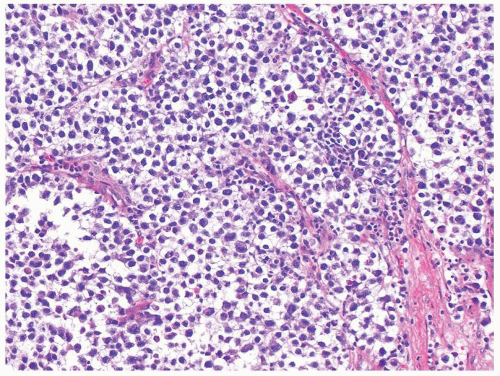

Figure 4.12.1 Classic seminoma composed of sheets of back-to-back monotonous neoplastic cells separated with associated lymphocytic infiltrate. |

Figure 4.12.2 Classic seminoma with relatively uniform round-to-polygonal cleared cells with ovoid nuclei. |

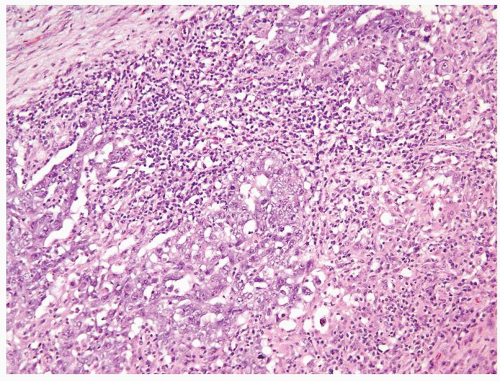

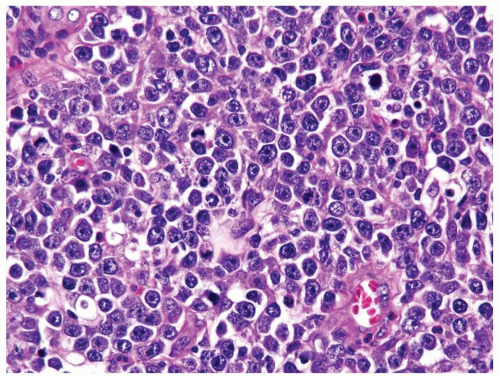

Figure 4.12.3 Large cell lymphoma with cells showing more pleomorphism than seminoma. Also the cells lack central prominent nucleoli in the majority of cells. |

Figure 4.12.5 Large cell lymphoma with less uniformity than seminoma. Also the cells lack central prominent nucleoli in the majority of cells. |

Figure 4.12.7 Lymphoma mimicking seminoma with prominent nucleoli, yet cells have amphophilic cytoplasm. |

|

Figure 4.13.1 Classic seminoma is composed of monotonous round-to-polygonal cleared cells with lymphocytic infiltrate. |

Figure 4.13.2 Classic seminoma with pseudoglandular spaces with uniform, loosely cohesive seminoma cells. |

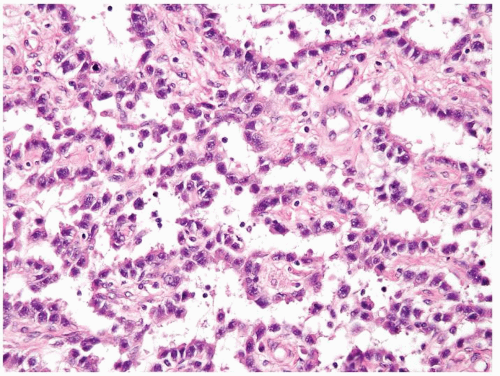

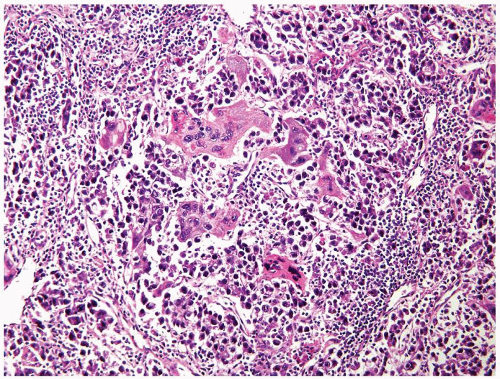

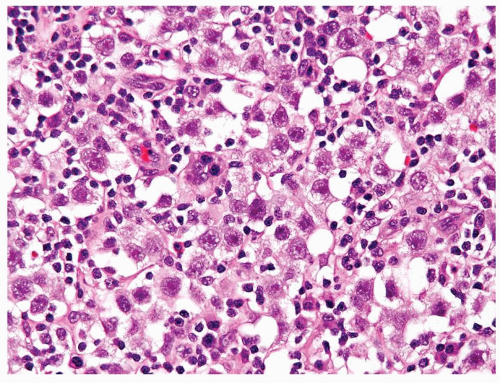

Figure 4.13.4 Yolk sac tumor composed of sheets of cells (right) with a more typical microcystic component (left). |

Figure 4.13.5 Same case as Figure 4.13.4 with cells mimicking seminoma, however lacking the seminoma cells’ uniform shape, vesicular nuclei, and large prominent eosinophilic nucleoli. |

Figure 4.13.7 Same case as Figure 4.13.6 with polygonal, medium-sized, cells with clear to eosinophilic cytoplasm and variably shaped nuclei. |

Figure 4.13.8 Same case as Figures 4.13.6 and 4.13.7 with more typical myxoid features. |

Figure 4.13.10 Same case as Figure 4.13.9 with diffuse positivity for AFP. |

|

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree