Tendon Repair

Preservation of mobility and function is a critical consideration in the repair of tendon injuries of the forearm and hand. While general surgeons may not be called upon to perform these repairs, it is important to understand the fundamental differences between the extensor and flexor tendon injuries, and the significance of the zones of the hand. In this chapter, the anatomy relating to the extensor and flexor tendons of the hand is explored, and the basic principles of tendon repair are described.

SCORE™, the Surgical Council on Resident Education, did not classify tendon repair.

STEPS IN PROCEDURE

Identify cut ends of tendon

Flex the wrist if necessary to bring ends into operative field

Handle ends of tendon as little as possible

Suture together with Bunnell or Mason-Allen stitch

Approximate epitenon with fine running suture of 6-0 nylon

HALLMARK ANATOMIC COMPLICATIONS

Missed injury

Scar formation leading to impaired mobility

LIST OF STRUCTURES

Flexor Muscles and Tendons

Pronator teres

Pronator quadratus

Flexor carpi radialis

Flexor carpi ulnaris

Flexor digitorum superficialis

Flexor digitorum profundus

Flexor pollicis longus

Extensor Muscles and Tendons

Brachioradialis muscle

Extensor carpi radialis longus

Extensor carpi radialis brevis

Extensor carpi ulnaris

Abductor pollicis longus

Extensor pollicis brevis

Extensor pollicis longus

Extensor indicis

Extensor digiti minimi

Extensor digitorum

Other Structures

Ulnar bursa

Radial bursa

Palmar aponeurosis

Superficial palmar arterial arch

Median nerve

Ulnar nerve

Carpal bones

Metacarpal bones

Phalanges

Carpal tunnel

Dorsal venous arch

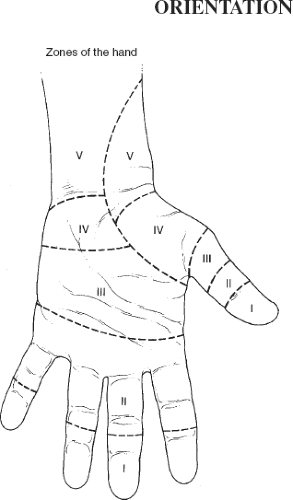

The flexor surface of the hand and wrist is divided into five zones, based on the anatomy (Fig. 40.1). Zone I is distal to the insertion of the superficial flexor muscle of the fingers. Zone II extends from zone I to the proximal side of the A1 pulley, formerly termed no-man’s land because the results of primary repair were poor. Zone III extends proximally from the A1 pulley to the flexor retinaculum. Zone IV is synonymous with the carpal tunnel, and zone V is proximal to the carpal tunnel.

The extensor aspect is also divided into zones, starting distally. These zones are defined as follows:

Dorsum of the distal interphalangeal joint

Dorsum of the middle phalanx

Dorsum of the proximal interphalangeal joint

Dorsum of the proximal phalanx

Dorsum of the metacarpophalangeal joint

Dorsum of the metacarpal bone

Dorsum of the wrist

Dorsum of the distal forearm

The site of a skin laceration may not correspond directly to the site of tendon laceration, depending on the angle of the cutting instrument and the position of the hand (finger extension vs. finger flexion) at the time of injury.

Surgical repair is only a small part of the treatment. Accurate diagnosis of all associated injuries, consideration of the timing of surgery (early vs. delayed repair), careful splinting postoperatively, and rehabilitation are all critical factors in achieving a good result. The tendon must be able to glide smoothly within its sheath. Scar formation between the repaired tendon and the sheath will severely compromise mobility.

Incision (Fig. 40.2)

Technical Points

Surgery on the hand and forearm is generally performed using nerve-block anesthesia. Tourniquet ischemia is helpful to produce a bloodless field in which structures can be dissected accurately. Prepare the entire hand and all fingers and drape it free, allowing it to rest on an operating arm board.

Plan an incision that zigzags along the volar digital surface (Fig. 40.2A). This incision affords excellent exposure while minimizing problems secondary to wound contracture. It may be possible to make such an incision by extending the original laceration, after debriding the edges.

Anatomic Points

This incision provides excellent exposure and is not attended by problems associated with contracture. Laterally; however, care must be taken to avoid the palmar digital neurovascular bundles (the dorsal arteries are insignificant). These bundles lie along the sides of the digital flexor sheaths, not along bone. Of the three components of the neurovascular bundle, the nerve is most palmar, and the vein is most dorsal.

The anterior (palmar) and medial aspects of the forearm, wrist, and hand include muscles and tendons involved with flexion of the extremity (Fig. 40.2B). One muscle, the palmaris longus, attaches to the palmar aponeurosis, and its tendon is superficial to the middle of the flexor retinaculum. Two muscles in the anterior compartment—the pronator teres and pronator quadratus muscles—are concerned solely with rotation of the radius relative to the ulna and, hence, do not extend into the wrist and hand region. Two other muscles—flexor carpi radialis and ulnaris—are powerful flexors that likewise do not flex into the hand and have no components that pass through the carpal tunnel. Three additional muscles are concerned with flexion of the digits, and all components of these muscles pass through the carpal tunnel. Two of these—flexor digitorum superficialis and profundus—each divide into four tendons that provide flexion of digits 2 to 5. The final function of the muscle, the long flexor muscle of the thumb, is solely flexion of the thumb (digit 1). Because flexor tendon injuries most often involve digital flexors, the following anatomic description will be limited to these muscles and their relationships.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree