Overview

A “Code Blue” is called when a patient on a medical-surgical ward is discovered pulseless and not breathing. The code team rushes in and begins CPR. “Does anybody know this patient?” the team leader barks as the team continues its resuscitative efforts. A few moments later, a resident skids into the room, having pulled the patient’s chart from the rack in the nurse’s station. “This patient is a No Code!” he blurts, and all activity stops.

As the Code Blue team members collect their paraphernalia, the patient’s young nurse wonders in silence. After all, she received sign-out on this patient only a couple of hours ago, and she was told that the patient was a “full code.” She thinks briefly about questioning the physician, but reconsiders. One of the doctors must have changed the patient’s code status to do not resuscitate (DNR) and forgotten to tell me, she decides. Happens all the time. So she keeps her concerns to herself.

Only later, after someone picks up the chart that the resident brought into the room, does it become clear that he had inadvertently pulled the wrong chart from the chart rack. The young nurse’s suspicions were correct—the patient was a full code! A second Code Blue was called, but the patient could not be resuscitated.1

Some Basic Concepts and Terms

All organizations need structure and hierarchies, lest there be chaos. Armies must have generals, large organizations must have CEOs, and children must have parents. This is not a bad thing, but taken to extremes, these hierarchies can become so rigid that frontline workers withhold critical information from leaders or reveal only the information they believe their leaders want to hear. This state can easily spiral out of control, leaving the leaders without the information they need to improve the system and the workers believing that the leaders are not listening, are not open to dissenting opinions, and are perhaps not even interested.

The psychological distance between a worker and a supervisor is sometimes called an authority gradient, and the overall steepness of this gradient is referred to as the hierarchy of an organization. Healthcare has traditionally been characterized by steep hierarchies and very large authority gradients, mostly between physicians and the rest of the staff. Errors like those in the wrong DNR case—in which a young nurse suspected that something was terribly wrong but did not feel comfortable raising her concerns in the face of a physician’s forceful (but ultimately incorrect) proclamation—have alerted us to the safety consequences of this kind of a hierarchy.

The Role of Teamwork in Healthcare

Teamwork may have been less important in healthcare 50 years ago than it is today. The pace was slower, the technology less overwhelming, the medications less toxic (also less effective), and quality and safety appeared to be under the control of physicians; everyone else played a supporting role. But the last half century has brought a sea change in the provision of medical care, with massively increased complexity (think liver transplant or electrophysiology), huge numbers of new medications and procedures, and overwhelming evidence that the quality of teamwork often determines whether patients receive appropriate care promptly and safely. For example, the outcomes of trauma care, obstetrical care, care of the patient with an acute myocardial infarction or stroke, and care of the immunocompromised patient are likely to hinge more on the quality of teamwork than the brilliance of the supervising physician.

After recognizing the importance of teamwork to safety and quality, healthcare looked to the field of aviation for lessons. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, a cluster of deadly airplane crashes occurred in which a steep authority gradient appeared to be an important culprit. Probably the best known of these tragedies was the 1977 collision of two 747s on the runway at Tenerife in the Canary Islands.

On March 27, 1977, Captain Jacob Van Zanten, a copilot, and a flight engineer sat in the cockpit of their KLM 747 awaiting clearance to take off on a foggy morning in Tenerife. Van Zanten was revered among KLM employees: as director of safety for KLM’s fleet, he was known as a superb pilot. In fact, with tragic irony, in each of the KLM’s 300 seatback pockets that morning there was an article about him, including his picture. The crew of the KLM had spotted a Pan Am 747 on the tarmac earlier that morning, but it was taxiing toward a spur off the lone main runway and it was logical to believe that it was out of the way. The fog now hung thick, and there was no ground radar to signal to the cockpit crew whether the runway was clear—the crew relied on its own eyes, and those of the air traffic controllers.

A transmission came from the tower to the KLM cockpit radio, but it was garbled—although the crew did hear enough of it to tell that it had something to do with the Pan Am 747. Months later, a report from the Spanish Secretary of Civil Aviation described what happened next:

On hearing this, the KLM flight engineer asked: “Is he not clear then?” The [KLM] captain didn’t understand him and [the engineer] repeated, “Is he not clear, that Pan American?” The captain replied with an emphatic, “Yes” and, perhaps, influenced by his great prestige, making it difficult to imagine an error of this magnitude on the part of such an expert pilot, both the co-pilot and flight engineer made no further objections. [Italics added]2

A few moments later, Van Zanten pulled the throttle and his KLM jumbo jet thundered down the runway. Emerging from the fog and now accelerating for takeoff, the pilot and his crew now witnessed a horrifying sight: the Pam Am plane was sitting squarely in front of them on the main runway. Although Van Zanten managed to get the nose of the KLM over the Pan Am, doing so required such a steep angle of ascent that his tail dragged along the ground, and then through the upper deck of the Pan Am’s fuselage. Both planes exploded, causing the deaths of 583 people. Thirty-five years later, the Tenerife accident remains the worst air traffic collision of all time.

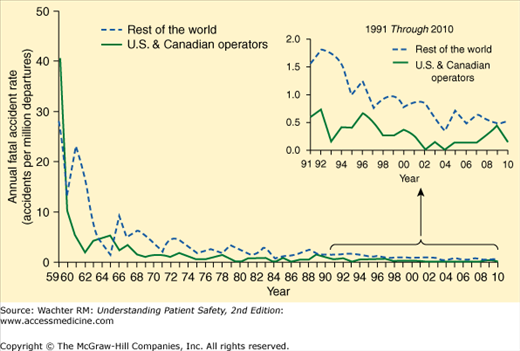

Tenerife and similar accidents taught aviation leaders the risks of a culture in which it was possible for individuals (such as the KLM flight engineer) to suspect that something was wrong yet not feel comfortable raising these concerns with the leader. Through many years of teamwork and communications training (called crew resource management [CRM], see Chapter 15), commercial airline crews have learned to speak up and raise concerns. Importantly, the programs have also taught pilots how to create an environment that makes it possible for those lower on the authority totem pole to raise issues. The result has been commercial aviation’s remarkable safety record over the past 40 years (Figure 9-1), a record that many experts attribute largely to this “culture of safety”—particularly the dampening of the authority gradient.

Figure 9-1

Commercial aviation’s remarkable safety record. Graphs shows annual fatal accident rate in accidents per million departures, broken out for U.S. and Canadian operators (solid line) and the rest of the world’s commercial jet fleet (hatched line). (Source: http://www.boeing.com/news/techissues/pdf/statsum.pdf, Slide 18. Used with permission from Boeing.)

How well do we do on this in healthcare? In a 2000 study, Sexton et al. asked members of operating room and aviation crews similar questions about culture, teamwork, and hierarchies.3 While attending surgeons perceived that teamwork in their operating rooms was strong, the rest of the team members disagreed (see Figure 15-3), proving that one should ask the followers, not the leader, about the quality of teamwork. Perhaps more germane to the patient safety question, while virtually all pilots would welcome being questioned by a coworker or subordinate, nearly 50% of surgeons would not (Figure 9-2). In a 2011 study, while these differences in perceptions among surgeons, anesthesiologists, and nurses had narrowed somewhat, they had not gone away.4