Socioeconomic status (SES), gender, and age are important variables in health and in obtaining health care in the United States.

SES and health

SES, a construct determined primarily by occupation, education, and income, correlates directly with health status. People with lower SES typically have poorer mental and physical health and decreased life expectancies than those with higher SES.

In the United States, approximately 85% of people with low SES are African American or Latino. Thus, these ethnic groups are at higher risk than the white population for several medical conditions (see

Chapter 20) and for dying young (see

Chapter 4). Among white Americans, those with low SES also are at higher risk for illness and early death.

Patients with high SES are more likely to seek treatment in a timely fashion, whereas low-SES patients are more likely to delay seeking treatment. Because of this delay, by the time a poor person is seen, he or she is often severely ill, making treatment more difficult and expensive. High-SES patients are also more likely to visit private doctors’ offices than are

low-income patients, who tend to go to hospital emergency rooms (ERs). Although hospital ER visits are more expensive than private doctors’ office visits, doctors in private practice can refuse to see patients who cannot pay them. In contrast, because of the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA), most hospital ERs are responsible for stabilizing every patient who presents for treatment, even those unable to pay.

In addition to the added difficulty that the poor face in obtaining health care, poorer diet (

Flegal et al., 2002) and habits, such as smoking and alcohol abuse, are seen more commonly in people with low SES and contribute to their increased risk for physical and emotional illness.

Gender and health

The sex difference in life expectancy starts early; males are more likely than females to die in the first 5 years of life and in young and middle adulthood. There also are sex differences in the risk of having certain illnesses in adulthood. For example, women are at higher risk than men are for developing autoimmune disorders (

Table 27-2).

Men are more likely to have heart disease than women are. However, when women, particularly those under 55 years of age, have their first heart attack, they are less likely than men to undergo diagnostic and therapeutic procedures and more likely than men to die (

Vaccarino et al., 1999). This sex difference in death rate after heart attack has been attributed to sex differences in reactions to medications, presentation of symptoms, and other physiological factors. However, it has also been attributed to missed or delayed diagnoses of heart problems in women resulting from the societal stereotype that only men have heart disease (

Wong, 2001).

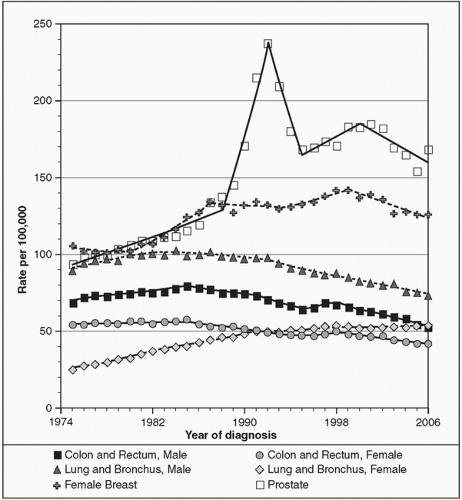

Smoking rates in American women, lower than in men in past years, now equal or exceed those of men. Thus, unsurprisingly, lung cancer rates in American women have been increasing.

Figure 27-2 shows incidence rates from 1974 to 2006 for the most common types of cancer in women and men.

No matter what the illness, gender differences exist in the frequency of seeking medical care. With the same symptom severity, women seek medical treatment more often than men do.

Age and health

Children are more likely than young and middle-aged adults to require medical treatment. However, of all age groups, the elderly are at highest risk for physical and mental illness. Although they comprise only 12% of the

population, the elderly currently incur at least 30% of all health care costs. Because of the increasing number of elderly Americans (see

Chapter 4), that percentage is expected to rise to 50% by the year 2020. The leading causes of death in the United States are listed in

Table 27-3.