A fistula is an abnormal communication between two epithelialized surfaces. An enterocutaneous fistula (ECF) is an abnormal communication between the bowel lumen and the skin. An enteroatmospheric fistula (EAF) is the communication between the bowel and the environment, with absence of skin continuity (open abdomen fistula).

Anastomotic leaks occurring during the first postoperative week are considered anastomotic line failures and not fistulas (no epithelialized tract has formed during that short period of time). They are usually detected because of drainage of intestinal material in the peritoneal cavity leading to the formation of an abscess or diffuse peritonitis. These patients are taken to surgery urgently either to repair the leak or to perform proximal diversion ostomies to ensure patient recovery.

Anatomic: on the basis of the affected segment

Gastrocutaneous, duodenocutaneous, enterocutaneous, and colocutaneous

Infectious and inflammatory (Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, tuberculosis, mycosis, diverticulitis, salmonellosis, amoebic abscess)

Iatrogenic (postoperative, open abdomen, postradiation)

Traumatic

Cancer

Foreign bodies

Fistula output:

High output: more than 500 mL per day. These fistulas are associated with a severe electrolyte and nutritional abnormalities.

Intermediate output: 200 to 500 mL per day

Low output: less than 200 mL per day

Deep EAFs drain the intestinal content into the abdominal cavity, giving rise to peritonitis. Mortality associated with this condition is higher than that of the superficial fistula that drains its content to the outside, creating an abdominal granulation wound with no diffuse contamination of the abdominal cavity.3

In surgical patients with secondary fistula, we characterize the most important adverse prognostic factors associated with the course of treatment, which are analyzed following the initial resuscitation and stabilization stage (48 to 72 hours). These factors include the following:

Open abdomen

Diameter larger than 5 mm; output greater than 500 mL per day

Presence of abscess and/or diffuse peritonitis, generalized sepsis

Need for mechanical ventilation

Inability to provide enteral feeding

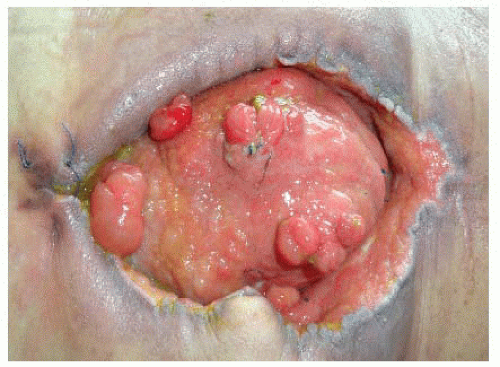

Presence of multiple fistulas (FIG 1)

Severe comorbidities (cancer, immunosuppression, radiation therapy, etc.)

The probability of a spontaneous fistula closure is related to different factors summarized in Table 1. Three risk groups are then established in order to arrive at an objective determination of the degree of complexity of the fistula, the goals of the proposed treatment, and the predicted clinical course (Table 2).

Risk group I: good prognosis. This group includes patients with no debilitating disease who are in good general condition and no systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), with fistulas that have a good probability of closing spontaneously (diameter <5 mm, output <200 mL per day, single). Treatment is limited to support, and surgical closure is not considered initially.

Table 1: Probability of Fistula Closure

Spontaneous Closure

No Spontaneous Closure

Esophageal, duodenal stump, jejunal

Enteric wall defects <1 cm

Fistula tracts >2 cm

No abdominal wall defect

Albumin level >25 g/L

No FRIEND factorsa

Output <200 ml/d

Conservative treatment

Gastric, Ligament of Treitz, Ileal

Enteric wall defects >1 cm

Fistula tracts <2 cm

Open abdomen

Albumin level <25 g/L

FRIEND factors

Output >500 ml/d

Surgical treatment

a Nonhealing ECFs are associated with FRIEND factors: Foreign body, Radiation,Inflammation, Infection, Inflammatory bowel disease, Epithelization of the fistula tract, Neoplasms, and Distal obstructions.

Table 2: Fistula Treatment Outcomes, Prognostic Risk Groups

Prognostic Group

I

II

III

Degree of complexity of the fistula

Low

Intermediate

High

Goals of the proposed treatment

Spontaneous closure

Early surgical closure

Late surgical closure

Predicted clinical course (mortality)

Exceptional mortality

Mortality 10%-25%

Mortality >25%

Risk group II: intermediate prognosis. This group includes patients in acceptable general condition with no SIRS but with fistulas that have small probability of closing spontaneously (diameter >5 mm, output >500 mL per day, multiple fistulas). The treatment strategy is to initially stabilize the patient and subsequently perform early surgical closure.

Risk group III: poor prognosis. This group includes patients in poor condition who are malnourished, with debilitating diseases, who exhibit SIRS, and who have fistulas with small probability of closing spontaneously. The initial goal of treatment is to reduce fistula output, to achieve granulation and ostomization of the fistula, as well as to care for the open abdomen. The surgical closure is performed at a later stage (6 to 12 months), once the patient has recovered and both objective and subjective signs of recovery are satisfactory.

The role of imaging is to define the anatomy, evaluate associated processes, and provide therapeutic alternatives for treatment.

Fistulograms are the most direct method of linking a cutaneous opening with the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. In the absence of sepsis, fistulograms may be the only imaging study needed. Two classes of contrast media are commonly used to evaluate the fistula tract, each with particular risks and benefits. Barium is a non-water-soluble media with high radiographic density, isotonic osmolarity, and an inert nature. Barium provides high-quality mucosal images, demonstrating areas of inflammation and the presence of fistula tracts with good accuracy. Unfortunately, if extravasated, barium causes significant peritoneal inflammation, including foreign body granulomas and peritoneal adhesions. Aqueous contrast agents, such as Gastrografin, are hyperosmolar and water-soluble. Water-soluble agents provide less mucosal detail; areas of inflammation, mucosal projections, and fistula tracts themselves may be missed. Gastrografin is rapidly absorbed within the peritoneal cavity if extravasated with minimal inflammation. To minimize risk and maximize benefits, water-soluble contrast material is often injected initially, followed by barium if no extravasation is seen and additional information is required.1,3,4

Small bowel follow-through (SBFT) studies provide a more global view of the intestinal tract. Multiple views are typically taken to optimize visualization. Ideally, barium is used for contrast as Gastrografin can be diluted as it moves distally through the GI tract. Fistulas with narrow lumen and distal fistulas may not be detected in SBFT studies. Previously opacified loops of bowel may complicate visualization of the fistula.

Ultrasound. Limitations of ultrasound include operator dependency, obesity, and difficulty of evaluating certain portions of the small bowel including duodenum and jejunum. Injection of hydrogen peroxide through the fistula orifice has been reported to increase the diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound from 29% to 88% in ECF complicating Crohn’s disease.5

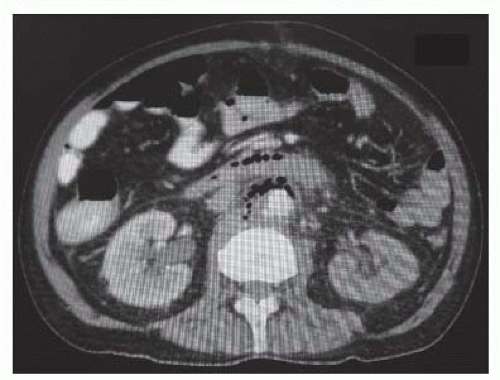

Computed tomography (CT) allows for the identification of extraluminal pathology, downstream disease, and inflammation (FIG 2).

Computed tomography enterography (CTE) uses “negative” contrast, which appears dark, allowing for distention of the bowel. With the concomitant administration of intravenous (IV) contrast that will delineate mucosa, negative contrast provides additional information concerning the mucosa surrounding a fistula tract.4

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a promising adjunct to primary imaging modalities. Its use in ECF evaluation is beginning to be understood.

The fundamental pillars for fistula management, initially described by Chapman,6 can be summarized by the SOWATS acronym: management of the Septic condition, Optimization of the nutritional status, surgical Wound care, fistula Anatomy, right Timing for surgery, and Surgical strategy.1 By adopting this strategy, they reduced ECF mortality from 40% down to 15%.

Sepsis: Associated infection is the primary cause of death in fistula patients. The initial management of a patient with an ECF, with or without associated infection, is fluid resuscitation to address dehydration and prevent renal

failure. Blood transfusion has to be considered if required. There are two stages associated with the management of infection:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree