Surgical Management of Complicated Diverticulitis: Perforation and Colovesical Fistula

Scott E. Regenbogen

DEFINITION

Diverticulitis is acute or chronic inflammation and/or infection caused by perforation of a colonic diverticulum. Acute, simple diverticulitis results from localized, contained contamination, without features of complex disease, and is typically amenable to medical therapy alone.

Complicated diverticulitis includes free perforation with peritonitis, abscess formation, fistula, or stricture and will typically require operation. Chronic or recurrent diverticulitis may be an indication for resection if the episodes are frequent, incur substantial morbidity, or fail to resolve with medical therapy.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Diverticulitis is often a clinical diagnosis. The syndrome of left lower quadrant pain, fever, and abdominal tenderness may also be consistent with irritable bowel syndrome, gastroenteritis, stercoral perforation, appendicitis, inflammatory bowel disease, urinary tract infection, aortic dissection or aneurysmal rupture, nephrolithiasis, pelvic inflammatory disease, ovarian torsion, and a variety of other causes of acute abdominal pain.

When diverticulitis is identified on computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen as segmental colon inflammation associated with diverticulosis, it must be distinguished from other causes of segmental colitis, including perforated neoplasm, ischemia, and Crohn’s disease. Details of clinical history, family history of colorectal cancer, and previous colon evaluation are helpful in excluding the latter two.

Except in the emergency setting, malignancy must be excluded, either by endoscopic evaluation or other means, because the principles of oncologic resection, including wide lymphadenectomy and en bloc resection, are typically violated in surgery for benign diverticular disease.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Patients with diverticulitis typically present with abdominal pain and fever. Because more than 90% of diverticulitis occurs in the sigmoid colon, the symptoms will typically localize to the left lower quadrant.

Free perforation may present as generalized peritonitis and/or sepsis.

In the presence of colovesical fistula, the patient may have irritative urinary symptoms or even pneumaturia or fecaluria, and there may be air or enteral contrast visible in the bladder. Occasionally, patients with colovesical fistula may not report a preceding episode of acute diverticulitis; rather, their initial presentation may be with symptoms of the fistula itself. Passage of urine per rectum is not common with colovesical fistulae from diverticulitis.

The clinical history should focus on the presence or absence of repeated episodes and symptoms suggesting fistulizing disease—gas or stool in the urine or per vagina.

In consideration of the differential diagnosis, the examiner should elicit any history consistent with inflammatory bowel disease or ischemic colitis and assess the patient’s risk factors for colorectal cancer (age, personal and family history of cancer or polyps, and whether any previous colorectal cancer screening evaluations have been performed).

Physical examination in the acute setting will reveal localized or generalized abdominal tenderness. Focal guarding in the left lower quadrant is typical. Diffuse rebound tenderness suggests generalized peritonitis from free feculent perforation or purulent peritonitis from abscess rupture. Abdominal wall erythema may suggest incipient colocutaneous fistula. In the chronic setting, patients may have fullness or a palpable mass.

Traditional recommendations for elective colon resection after two episodes of uncomplicated diverticulitis have generally been abandoned. Instead, elective colectomy is recommended on a case-by-case basis, depending on age, comorbidity, severity and frequency of attacks, and the success of medical therapy.

Elective resection is often advised after recovery from an episode of complicated diverticulitis managed with medical therapy and/or percutaneous drainage.

Urgent operation may be indicated for free perforation with sepsis.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Typical findings on CT scan of the abdomen include segmental colonic inflammation and pericolonic fat stranding within an area of diverticulosis. There may be extraluminal air or fluid or a contained abscess. Intravenous and oral contrast administration is helpful, although not essential. Rectal contrast is generally unnecessary, except to help with delineating a fistula.

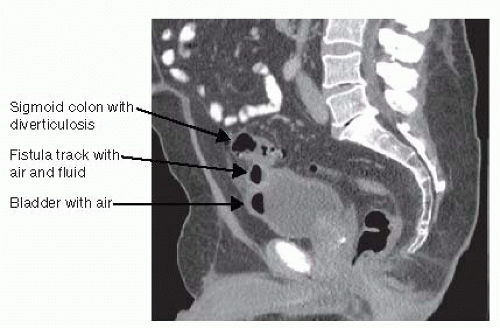

CT is the most sensitive test for diagnosing colovesical fistula (FIG 1). Other options include contrast enema (FIG 2), CT or fluoroscopic cystography, cystoscopy, colonoscopy, or oral administration of undigested material (e.g., charcoal, poppy seeds) to be observed for in the urine. In some cases, colovesical fistula may be a clinical diagnosis based on the presence of pneumaturia and/or fecaluria alone.

FIG 1 • Sagittal CT image demonstrating sigmoid diverticulitis with a fistula track and air in the bladder consistent with colovesical fistula.

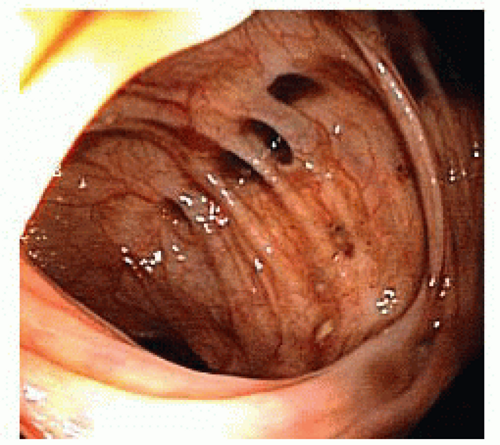

Colonoscopy (FIG 3) is advisable for evaluation of diverticulitis and colovesical fistula in order to exclude a perforated malignancy, which can have similar clinical presentation and radiographic appearance. The presence of malignancy would warrant an oncologic mesenteric lymphadenectomy and en bloc resection of involved bladder wall, whereas the fistula may simply be divided in cases with benign inflammatory etiology.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

When patients present with diffuse peritonitis and sepsis, urgent operation may be required. Broad-spectrum antibiotics should be administered and the patient should be well resuscitated with intravenous fluid prior to surgery.

Every effort should be made before surgery to mark acceptable sites on the abdominal skin for stoma creation bilaterally. Consideration may be given to placement of ureteral stents preoperatively if it can be performed without undue delay.

FIG 2 • Barium enema demonstrating sigmoid diverticulosis with a fistula track and contrast filling the bladder.

Decision making should be centered on the patient’s clinical condition, the severity of pelvic sepsis, the suitability for colorectal anastomosis, and the ability to safely resect the inflammatory segment.

Options for surgical approach in the emergency setting include

Proximal diversion without resection

Resection with end colostomy and rectal stump closure (Hartmann procedure)

Resection with primary anastomosis, with or without diverting loop ileostomy

Laparoscopic lavage and drainage

Complete colonoscopy in the elective setting should be performed in order to exclude a perforated malignancy that presented as perforated diverticulitis or synchronous malignancy.

Cystoscopy and urine cytology may be considered in cases of colovesical fistula if there is suspicion for a primary bladder malignancy.

Consideration should be given to prophylactic placement of ureteral catheter(s) to assist with identification of the ureter, if it appears to be involved with the inflammatory segment.

Laparoscopic approaches to complex diverticular disease and colovesical fistula are appropriate in hemodynamically stable patients among surgeons with adequate laparoscopic colorectal surgery skills and training. Hand-assisted and straight laparoscopic techniques have similar short- and long-term reported outcomes.

If inflammation is severe and there is intention to perform a Hartmann procedure with end colostomy or a colorectal anastomosis with diverting loop ileostomy, the patient should undergo preoperative evaluation and counseling by an enterostomal therapist, including marking suitable locations for a stoma on the abdomen, either unilaterally or bilaterally, if the operative plan will depend on intraoperative findings.

Mechanical bowel preparation with or without oral antibiotics is a controversial topic. There is no definitive evidence for or against bowel preparation. However, if there is intention to use a circular end-to-end stapling device placed per anus, mechanical bowel preparation or rectal enema should be administered to clear stool from the rectum. If a colorectal anastomosis and diverting loop ileostomy is planned, mechanical bowel preparation is recommended to avoid leaving a column of stool between the ileostomy and the downstream anastomosis.

Prophylactic antibiotics to cover skin flora, enteric gram negatives, and anaerobic bacteria should be administered before making the incision.

Appropriate pharmacologic and/or mechanical prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism is recommended.

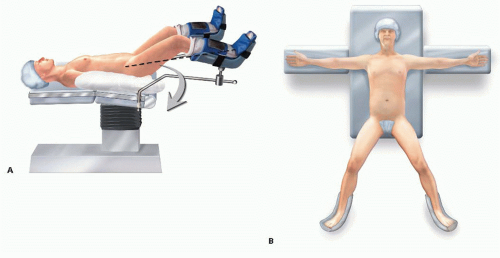

Positioning

The patient is placed in modified lithotomy position (FIG 4A) or supine with legs abducted on a split-leg table (FIG 4B) to provide access to the anus.

If a laparoscopic approach is used, consideration may be given to a position-assisting device, such as a beanbag, to prevent the patient from sliding during extreme positioning changes.

If stoma markings were performed preoperatively, these should be redrawn with a marker that will remain visible after skin preparation.

TECHNIQUES

LAPAROSCOPIC ELECTIVE SIGMOID COLECTOMY, BLADDER REPAIR

Abdominal Access and Port Placement

The abdomen may be accessed via a percutaneous Veress needle or an open Hasson cannula technique.

Typical port placement is depicted in FIG 5. A 12-mm camera port is placed at the umbilicus. Three working ports are inserted, including a 5-mm port in the right upper quadrant, a 12-mm port in the right lower quadrant (preferably at a potential diverting loop ileostomy site), and a 5-mm port in the left lower quadrant (preferably at a potential colostomy site).

Isolation and Division of the Inferior Mesenteric Artery Pedicle

In order to gain access to the proximal inferior mesenteric artery (IMA), the gastrocolic omentum is elevated over the transverse colon, into the upper abdomen, with the patient in steep Trendelenburg position, with the operating table tilted toward the right. The small bowel is brought to the right upper quadrant and out of the pelvis.

Elevation of the rectosigmoid mesentery with a grasper through the left lower quadrant port toward the left lower quadrant, demonstrates the IMA as a ridge in the sigmoid colon mesentery and exposes a plane between the mesentery and the retroperitoneum on the medial peritoneal fold of the mesentery. With cautery attached to Endo Shears brought through the right lower quadrant port, a long incision is made in the medial peritoneal fold of the mesentery along a clear space seen between the IMA and the retroperitoneum (FIG 6).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree