KEY POINTS

Frailty, dementia, and geriatric syndromes have recently been identified as major factors in the development of postoperative complications in the elderly.

Emergency surgery in the elderly carries a mortality rate that is 3 to 4 times that seen after elective surgery.

Impaired cardiac function is responsible for more than half of the postoperative deaths in elderly patients, so careful attention must be paid to intravascular volume status in the perioperative period.

In elderly patients with acute appendicitis or acute cholecystitis, one-third lack fever, one-third lack an elevated white blood cell count, and one-third lack physical findings of peritonitis.

Physiologic age, not chronologic age, is the consequence of diminished functional reserve due to comorbid conditions, and is the major predictor of perioperative morbidity and mortality in the elderly.

Laparoscopic approaches to surgical management, including the use of exploratory laparoscopy to rule out surgical disease, are associated with fewer complications and more rapid recovery in the elderly.

New tools exist to help assess perioperative risk in geriatric patients, in addition to medical comorbidities. They include identification of geriatric syndromes, frailty indicators.

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

As our population ages, a dramatic increase is anticipated in the number of geriatric patients that will require various surgical interventions. The U.S. Census Bureau estimates that the number of people age 65 years and older will double between 2010 and 2050.1 By 2030, people 65 years of age or older will account for 20% of the overall population. Furthermore, half of all Americans currently alive can expect to reach the ninth decade of life.2 Geriatric patients represent a unique surgical challenge due to the complexity of comorbid conditions coupled with the physiologic changes that occur with aging. As a result of these considerations, and in response to research and specialized care protocols which are tailored for its age range, geriatric surgery has emerged as a subspecialty of surgery much as pediatric surgery developed decades ago.

Physiologic age is of greater importance in perioperative management of elderly surgical patients than chronologic age because it takes into account the burden of comorbid disease. It is, therefore, an accurate predictor of postoperative morbidity and mortality. The hallmark of physiologic aging or “senescence” is decreased functional reserve of critical organ systems, resulting in the decreased ability of these systems to respond to a challenge, with surgical stress being a prime example. The age of 70 years is typically accepted as the start of senescence because age-related organ dysfunction and the development of comorbid conditions sharply increases between ages 70 and 75 years.3 This criterion for senescence is in contrast to clinical studies published just 50 years ago that categorized elderly patients as those over the age of 55 years. With improved technologies and expanded criteria for surgical interventions in extremely aged patients, increased awareness of the special needs of this population is required to ensure a comprehensive preoperative assessment, delivery of optimal surgical care, and minimization of postoperative complications. It is also critical that a multidisciplinary approach be developed, which involves the patient and their home caregivers, geriatric physicians, surgeons, and, at times, specialists in intensive care.

It is estimated that, by the year 2030, there will be 70 million people >65 years old in the United States, a stark increase over the 35 million in 2000.4 This ever growing elderly population will increasingly require surgical care, and patients >65 years old already account for approximately 60% of the general surgeon’s workload.5 Patients >65 years old account for approximately 50% of all emergent operations and 75% of operative mortality.4 These statistics challenge a surgeon to have an in-depth understanding of the careful perioperative evaluation required in elderly patients and the tailoring of surgical interventions based on the unique changes in physiologic reserve and comorbid conditions that make elderly patients more susceptible to postoperative complications.

The goal of this chapter is to highlight salient management strategies for aged surgical patients to achieve optimal care and reduce postoperative complications. Particular problems in the elderly population which impact on surgical care include the potential delay in surgical treatment due to a missed or delayed diagnosis secondary to an atypical presentation of disease, and the postponement of needed elective surgery because of the misconception that an elderly patient will suffer a poor outcome as a result of advanced age alone. For example, elective inguinal and umbilical hernia repairs are often postponed due to age bias; this can lead to potentially devastating consequences of bowel ischemia, gangrene, and perforation, to which elderly patients respond poorly. As a result, emergency hernia repairs are among the most common procedures performed in older patients; approximately 40% of hernia repairs are performed for incarceration or bowel obstruction in patients >65 years old.5 Emergency repair of hernias is associated with an increased morbidity rate of approximately 50% and a mortality rate ranging between 8% to 14%; a significant increase from the 2% mortality rate following elective repair in age-matched patients.5

Another significant consideration with the geriatric population is the need to balance optimal health care delivery with rising health care costs. The goal of surgical therapy in the elderly is to provide needed interventions which result in maximum benefit to the patient without compromising quality of life or unwanted adverse outcomes. For example, screening for breast or colorectal cancer should be performed if the patient has a reasonable expectation of quality and quantity of life. An extensive and/or invasive workup should not be performed if the patient would not tolerate the anticipated therapeutic intervention.

Finally, a fifth of elderly patients die in ICU settings and half of them require mechanical ventilation and a quarter undergo cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the days before their death.6 Although Medicare expenditures in the last year of life are approximately five times higher than in nonterminal years, the actual quality of care at the end of life is often poor due to debilitating and persistent symptoms. Even more worrisome is the fact that some patients receive treatments which are inconsistent with their preferences for end of life measures. An additional component of geriatric surgery is therefore the provision of compassionate care that is more focused on symptomatic relief than on cure in patients who are near the end of life.

PHYSIOLOGY OF AGING

Elderly surgical patients are a heterogeneous cohort with various degrees of functional impairments and comorbid burdens. The “young old patient” may lead an active lifestyle with few, if any, comorbid conditions. But even for this seemingly healthy individual, it is crucial to remember that there are inherent physiologic changes that occur with aging and which affect every organ system. These physiologic changes may become more apparent and clinically consequential with the stress of major illness and operative interventions.

An important criterion in the geriatric surgery patient is the frailty score. Frailty is a syndrome associated with advanced age that results from decreased physiologic reserve and which makes patients less resistant to major stressors such as invasive surgical procedures. Frail patients are prone to poorer outcomes, due to falls, disability, impaired ability to perform activities of daily living (ADLs), prolonged hospitalizations and an increase in mortality.1 Frail patients are more likely to require discharge to skilled nursing facilitiespostoperatively. Prior to surgery,frailpatients and their family members should be aware of this possibility. Therefore, the frailty score is a more accurate representation of the patient’s physiologic age.

Chronologic age is rarely an accurate predictor of morbidity and mortality from surgical interventions. It is, however, an accurate marker for declining physiologic reserve and the likelihood of the presence of comorbid conditions. These place elderly patients at higher risk because of impaired cardiac, pulmonary, renal, and neurological reserves, which increase the morbidity and mortality risk of surgical interventions. Physiologic age, in addition to comorbid conditions, more accurately predicts surgical outcomes in the elderly than chronologic age. The physiologic changes of aging are summarized in Table 47-1.

| AGE-RELATED CHANGES | CLINICAL CONSEQUENCES | BEST PRACTICES |

|---|---|---|

BODY COMPOSITION | ||

• Significantly decreased muscle mass, accounting for much of decreased lean tissue mass • Increased fat mass | • Erosion of muscle mass during acute illness may result in strength rapidly falling below important clinical thresholds (e.g., impaired coughing, decreased mobility, increased risk of venous thrombosis) • Altered volumes of drug distribution | • Maintain physical function through effective pain relief, avoiding tubes, drains, and other “restraints,” early mobilization, and assistance with mobilization. • Minimize fasting, provide early nutritional supplementation or support (both protein-calorie and micronutrient). • Adjust drug dosages for volume of distribution. |

Respiratory | ||

• Decreased vital capacity • Increased closing volume • Decreased airway sensitivity and clearance • Decreased partial pressure of oxygen | • Less effective cough • Predisposition to aspiration • Increased closure of small airways during tidal respiration, especially postoperatively and when supine, leading to increased atelectasis and shunting • Predisposition to hypoxemia | • Provide early mobilization, assumption of upright rather than supine position. • Ensure effective pain relief to allow mobilization, deep breathing. • Provide routine supplemental oxygen in the immediate postoperative period, and then, as needed. • Minimize use of nasogastric tubes. |

Cardiovascular | ||

• Decreased maximal heart rate, cardiac output, ejection fraction • Reliance on increased end-diastolic volume to increase cardiac output • Slowed ventricular filling, increased reliance on atrial contribution • Decreased baroreceptor sensitivity • Thermoregulation • Diminished sensitivity to ambient temperature and less efficient mechanisms of heat conservation, production, and dissipation • Febrile responses to infection may be blunted in frail or malnourished elderly and those at extreme old age. | • Greater reliance on ventricular filling and increases in stroke volume (rather than ejection fraction) to achieve increases in cardiac output • Intolerant of hypovolemia • Intolerant of tachycardia, dysrhythmias, including atrial fibrillation • Predisposition to hypothermia (e.g., decline in body temperature during surgery is more marked unless preventive measures are taken) • If there is hypothermia, shivering may result, associated with marked increases in oxygen consumption and cardiopulmonary demands. • Fever may be absent despite serious infection, especially in frail elderly. | • Use vigorous fluid resuscitation to achieve optimal ventricular filling. • Nonvasoconstricting inotropes and afterload reduction may be more effective, if pharmacologic support is required. • Use active measures to maintain normothermia during surgical procedures and to rewarm after trauma: warmed IV fluids, humidified gases, warm air. • Maintaining intraoperative normothermia reduces wound infections, adverse cardiac events, and length of hospital stay. • Be aware of hypothermia in trauma resuscitation. |

| Renal function, fluid-electrolyte homeostasis | ||

• Decreased sensitivity to fluid, electrolyte perturbations • Decreased efficiency of solute, water conservation, and excretion • Decreased renal mass, renal blood flow, and glomerular filtration rate • Increased renal glucose threshold | • Predisposition to hypovolemia • Predisposition to electrolyte disorders, (e.g., hyponatremia) • Predisposition to hyperglycemia • Predisposition to hyperosmolar states | • Pay meticulous attention to fluid and electrolyte management. • Recognize that a “normal” serum creatinine value reflects decreased creatinine clearance because muscle mass (i.e., creatinine production) is decreased concurrently. • Select drugs carefully: Avoid those that may be nephrotoxic (e.g., aminoglycosides) or adversely affect renal blood flow (e.g., NSAIDs). • Adjust drug dosages as appropriate for altered pharmacokinetics. |

The terms “frailty,” “disability” and “comorbidity” have mistakenly been used interchangeably. These terms have very different connotations for the geriatric patient. Disability is defined as dependence on assistance with ADLs, and contributes to the risk of frailty. Comorbidity is defined as the presence of two or more existing diseases, and is quantified by the Charlson comorbidity index.7 Geriatric assessment markers for frailty and disability include cognition, albumin level, history of falls, hematocrit level, and dependance on assistance with ADLs. These objective measures have been shown to predict six month postoperative mortality or the need for long term institutionalized care after surgery.7 (Table 47-2)

| MARKER | MEASURE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Frailty | Cognition (Mini-Cog test ≤3) Falls ≥ 1 in last six months Albumin ≤3.3 gm/dL Hematocrit ≤35% | Disability | DependanceDependence on ≥1 activity of daily living | Comorbidity | Charlson index ≥3 |

SURGERY IN THE ELDERLY

It is critical in the assessment of any elderly patient to maintain a high index of suspicion for surgical pathology. Elderly patients often present with atypical symptoms and/or a misleadingly benign-appearing abdominal examination that may mask an intra-abdominal catastrophe. The effects of age-related impairments in immune function can be compounded by co-existent medical problems and altered mentation as a result of dementia, drugs, infection, or dehydration.

Acute appendicitis and acute cholecystitis are classic examples of common acute surgical pathologies in which elderly patients have a delay in diagnosis or misdiagnosis. This often leads to higher rates of perforation and complications that adversely affect morbidity and mortality.8 Biliary tract disease, including acute cholecystitis, is the most common indication for surgical intervention in the elderly. This is likely related to age-related changes within the biliary system, such as increased lithogenicity of bile and an increased prevalence of cholelithiasis. Delayed diagnosis due to atypical or misleading symptoms may lead to complications such as ascending cholangitis, gallbladder perforation, or gallstone ileus.

Elderly patients with acute peritonitis may not present with typical symptoms of acute abdominal pain, fever, or leukocytosis, due to a depressed immune response. In older patients presenting with acute appendicitis, the initial diagnosis is correct in less than half of the patients.8 A careful assessment and high index of suspicion are crucial to achieve timely operative intervention.

PREOPERATIVE ASSESSMENT

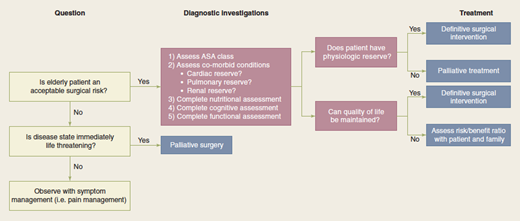

Surgical risk increases with advancing age as a consequence of physiologic decline and the development of comorbid conditions that make the elderly surgical patient more susceptible to postoperative complications. Geriatric patients may have masked vulnerabilities due to their unique physiologic state that requires a more detailed preoperative assessment. Comorbid illness serves as the basis for the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ (ASA) physical status classification. This is a valuable tool for identifying elderly patients who are at high risk for postoperative complications because it is based on organ system dysfunction and severity of functional impairment. It helps to identify subgroups of patients in whom appropriate measures should be taken to reduce the risk of adverse outcomes. Importantly, it also quantifies the risks of morbidity and mortality for emergency surgery.A careful assessment of potential problems in the perioperative period combined with implementation of preventative measures can significantly reduce complications associated with general anesthesia in the elderly patient.9 A useful algorithm for the preoperative assessment of an elderly surgical patient is provided in Fig. 47-1.

Cardiac complications are the leading cause of perioperative complications and death in surgical patients of all age groups, but particularly among the elderly. This is because patients often have co-existing cardiac dysfunction, combined with normal physiologic decline and poor functional reserve. The combined effect of depletion of intravascular volume, age-related impairment of response to catecholamines, and increased myocardial relaxation time adversely affects the cardiac function of an elderly patient under stress in the perioperative period.10 Aging has been demonstrated to cause a decrease in cardiac output by approximately 1% per year. Older individuals fail to augment heart rate to the same extent as younger individuals. More importantly, the ability to increase cardiac output with aging is dependent on ventricular dilatation, which is determined by preload.11 Therefore careful attention must be paid to volume status in the perioperative period. Dehydration or poor resuscitation may occur in elderly surgical patients for a variety of reasons, and both are poorly tolerated. Over one half of all postoperative deaths in elderly patients and 11% of postoperative complications are a result of impaired cardiac function under physiologic stress. Incomplete emptying of the ventricle at end systole and subsequent reduction in ejection fraction is characteristic of the aging heart.10 Reduced distensibility, in addition to acute stressors, leads to impaired coronary perfusion and cardiac ischemia.

As a result, the physiologic stress of general anesthesia and surgical interventions can unmask the limited cardiac reserve of the elderly patient. Poor reserve may become evident with increased myocardial oxygen demand resulting from tachycardia or loss of vascular tone from the vasodilatory effects of many general anesthetic agents. An important predictor of surgical outcomes and cardiac complications in the elderly is congestive heart failure (CHF). CHF is present in approximately 10% of patients older than 65 years and is the leading cause of postoperative morbidity and mortality.12 This prevalence will likely increase as percutaneous interventions and medical therapy prolongs survival from myocardial ischemia and acute myocardial infarction. Therefore, identifying correctable and uncorrectable cardiovascular disease is critical before elective surgical interventions.

Pulmonary complications are a major source of morbidity and mortality in elderly surgical patients. The age-related changes that occur in the respiratory system limits the maximal breathing capacity by age 70 to 50% of the capacity present at age 30.12 In addition, there is a decline in the forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) with advancing age. It is estimated that humans lose 35 mL of their FEV1 per year over the age of 35 years old. There is a slow decline between ages 35 and 65 years old followed by a much more progressive decline at approximately 75 years of age.13 Pulmonary complications account for up to 50% of postoperative complications and 20% of preventable deaths.14 Risk factors for pulmonary complications include a positive smoking history, presence of shortness of breath, or clinical evidence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. All elderly patients undergoing major surgical interventions should have a baseline chest radiograph. Screening spirometry can be performed to determine forced vital capacity and FEV1. A baseline arterial blood gas measurement also will help to identify hypoxemia and hypercapnia, both of which may increase postoperative complications. If abnormalities are found, perioperative use of bronchodilators and incentive spirometry may be invaluable. When possible, regional anesthetic techniques may provide excellent analgesia while helping to reduce the postoperative pulmonary complications associated with general anesthesia and endotracheal intubation.

Renal complications are also increased in elderly surgical patients in the perioperative period. Renal size and volume decrease with age, accompanied by intrarenal vascular changes. There is a decrease in the number of glomeruli and nephron mass, resulting in decreased filtration area. Serum creatinine concentration is an insensitive indicator of renal function in the elderly, however.10 The physiologic age-related changes in renal function increase susceptibility to renal ischemia as well as to nephrotoxic agents. Age-related changes in renal function result from progressive glomerulosclerosis and reduction in renal mass resulting in decreased creatinine clearance and glomerular filtration rate. This is worsened by a decline in cardiac output with increasing age and subsequent decrease in renal blood flow. It has been shown that patients with impaired glomerular filtration rate are more susceptible to volume changes that occur in the perioperative period. Furthermore, decreased drug elimination can potentiate the effects of nephrotoxic drugs and prolong the sedative effects of anesthetics and narcotic used for postoperative pain management.12 Acute renal failure is proven to dramatically increase morbidity and mortality in elderly patients. The mortality risk of perioperative renal failure in all patients is approximately 50% and may be even higher in elderly patients. Therefore, careful management of fluid and electrolyte status is prudent to avoid imbalances and limit exposure to nephrotoxic diagnostic studies and medications in the perioperative period. Patients >70 years old may be susceptible to the nephrotoxic effects of certain anesthetic agents, and thus should be protected by hydration and diuresis, as long as they can tolerate the fluid load.10 Prompt recognition of renal compromise, marked by an elevation of blood urea nitrogen or creatinine levels or oliguria, requires aggressive correction of underlying causes. Furthermore, electrolyte imbalances can lead to potentially devastating cardiac conduction abnormalities and arrhythmias.12 Although not routinely advocated in younger patients, elderly patients should have routine electrolyte panels and urinalysis before all surgical interventions to identify potential renal dysfunction.15 Underlying causes of abnormalities found on screening should be corrected before surgery and may necessitate intravascular volume repletion to ensure adequate renal perfusion perioperatively.

A functional evaluation which includes an assessment of the cognitive level of functioning is an important part of the preoperative evaluation of elderly surgical candidates. This ensures that operative intervention will not significantly impair the quality of life of an elderly surgical candidate. The ability to withstand the stress of surgical interventions is dependent on functional reserve and the ability to build an appropriate response to peri-operative stress.10 The ability to perform ADLs such as feeding, dressing, bathing, and toileting have been correlated with postoperative morbidity and mortality (Table 47-2). Preoperative functional assessment can be measured by hand grip strength, timed “up and go,” and functional reach tests7. All of these tests independently predicted better recovery and shorter time to recover ADLs after major surgery. In addition, these tests provide an accurate assessment of a patient’s muscle mass, nutritional status, coordination, gait speed, balance, and mobility.5 Proper functional assessment will accurately predict rehabilitation needs, estimate biologic reserve, and indicate an enhanced risk of complications.10

The functional status of an elderly patient is directly and inversely correlated to pulmonary and cardiac complications that may ensue following surgical interventions. For example, functional impairment often leads to immobility, which can lead to increased risk of postoperative atelectasis, pneumonia, deep vein thrombosis (DVT), and pulmonary embolism. Furthermore, proper functional assessment has been shown to improve diagnostic and therapeutic outcomes as well as to lead to identification of previously undiagnosed conditions that may be treatable preoperatively or managed peri-operatively.10

Cognitive function often is overlooked in the preoperative assessment of patients, because patients are not typically formally evaluated before surgical intervention (i.e., mini-mental state examination). However, knowledge of baseline cognitive function provides invaluable information because subtle changes in cognition often herald postoperative complications, such as underlying infection. Cognitive impairment, including delirium and confusion commonly occur in the elderly patient during the early postoperative period and can result in increased morbidity, delayed functional recovery, and prolonged hospitalizations. The etiology of this postoperative cognitive dysfunction may be multifactorial. Advanced age, history of alcohol abuse, baseline cognitive disturbance, hypoxia, and hypotension have all been shown to be contributing factors.16 It is crucial that careful attention be paid to adequate postoperative analgesia to improve recovery while avoiding compromise of cognitive function. Methods such as “Beer’s Criteria” are useful tools to assess whether a particular drug is appropriate for the aged patient. Finally, dementia is a known predictor of poor long-term survival.

A formal nutritional assessment is invaluable in the perioperative assessment of elderly patients. Poor nutritional status in elderly patients is common and results from the interplay between physiologic, psychosocial, and economic changes that accompany the aging process. Elderly patients may have poor nutritional status because of either poor intake due to the underlying illness or pre-existing comorbid conditions. In the outpatient setting, it is estimated that 9% to 15% of persons >65 years old are malnourished. This increases to 12% to 50% and 25% to 60% in the acute inpatient hospital setting and chronic institutional settings, respectively.17 The cycle of frailty that occurs with chronic undernutrition or malnutrition can lead to progressive functional decline, loss of muscle mass, and decreased oxygen consumption and metabolic rate in this population.17 Therefore, adequate assessment of nutritional status of these patients preoperatively and the prompt institution of nutritional support is of utmost importance. This is an integral component of the preoperative assessment, considering that nutritional status is a proven independent predictor of surgical outcomes. Deterioration of a patient’s nutritional state in the perioperative period contributes to adverse outcomes. Poor nutrition can lead to increased nosocomial infections, multiorgan system dysfunction, poor wound healing, and impaired functional recovery. Therefore, nutritional assessment and support, if necessary, not only give patients additional reserve to minimize postoperative complications, but aid in appropriate wound healing, functional recovery, and rehabilitation.

Protein energy malnutrition (PEM) also can result from maintaining compromised surgical patients nil per os (NPO). PEM may occur quickly in the elderly, malnourished surgical patient in a hypermetabolic state induced by stress of illness and surgery. The physiologic consequences of PEM are multiple and include anorexia, hepatic dysfunction, decreased mucosal proliferation, and sarcopenia.17 A good marker of PEM is hypoalbuminemia, also shown to be an extremely accurate predictor of surgical outcomes. The incidence of postoperative complications is increased in patients with serum albumin levels <3.5 g/L.17 Current recommendations indicate that if patients demonstrate compromise of nutritional status as defined by >10% weight loss and serum albumin level <2.5 g/dL, they should be considered for a minimum of 7 to 10 days of nutritional repletion prior to surgery.10

The significant impact of nutritional status on surgical outcomes and functional recovery in the elderly population after surgical intervention underscores the importance of an accurate preoperative nutritional assessment. In busy surgical practices, the question arises as to whether this can be done in a simple, reproducible, and cost-effective manner while obtaining vital information. There are several methods of assessing nutritional status, including anthropomorphic measures (i.e., body mass index), biochemical laboratory values (i.e., transferrin, albumin, and prealbumin), and clinical assessments.17

The Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) is an established, validated nutritional assessment tool which can be useful for the preoperative assessment of the elderly surgical candidate. The MNA consists of a screening portion assessing the patient’s current body mass index, food intake and weight loss, mobility, and presence of stressors, depression, or dementia, all of which can exacerbate undernutrition or malnutrition in the elderly patient. The goal is to identify patients at risk for malnutrition, and who need further evaluation involving a more complete psychosocial assessment and determination of mode of feedings. This tool helps to identify undernutrition and malnutrition in older individuals, >65 years old, and helps to direct timely interventions which result in improved functional recovery.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree