|

Typical Clinical Features |

Microscopic Features |

Ancillary Investigations |

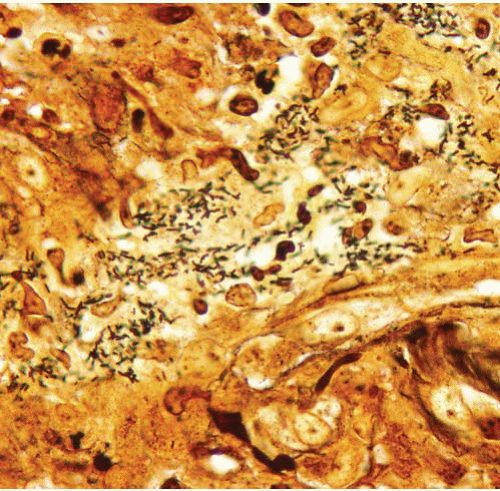

Bacillary angiomatosis |

Immunocompromised patients with cutaneous lesions |

Lobulated proliferation of capillarysized vessels

Aggregates of neutrophils, leukocytoclastic debris |

Warthin-Starry stain (pH 4.0), shows clumps of small curved rods of Bartonella henselae |

Verruga Peruana (Oroya fever) |

Skin lesions in persons in endemic areas (Peru) |

Cutaneous vascular proliferation with plump endothelial cells and inflammation |

Weak staining of Bartonella bacilliformis organisms with Giemsa |

Papillary endothelial hyperplasia |

Within thrombi anywhere in the body, often distal extremities and in hemorrhoids; essentially a variant of organizing thrombus |

Fibrin cores coated by monolayers of endothelial cells, typically all within a vessel |

Typically not required |

Intravascular fasciitis |

Distal extremity nodules in young adults |

Intravascular myofibroblastic proliferation accompanied by lymphocytes and osteoclast-like giant cells |

SMA+, calponin+, caldesmon−, desmin−

Vascular markers (CD34, CD31, ERG)− |

Intravascular leiomyomatosis |

In women with uterine leiomyomas that extend into veins |

Essentially a leiomyoma in a vessel; perpendicularly oriented fascicles of brightly eosinophilic cells with blunt-ended nuclei without mitotic activity |

SMA+, calponin+, caldesmon+, desmin+

Vascular markers (CD34, CD31, ERG)− |

Angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia (epithelioid hemangioma) |

Adults (20-40 y), head-neck region, single or multiple smooth papules or plaques (superficial)

Some cases in bone |

Lobular vascular proliferation surrounded by lymphoid cuff, often associated with damaged artery

Vessels lined by epithelioid endothelial cells, background eosinophils—benign |

Typically not required; ZFP36-FOSB fusions detected in atypical cases suggests that at least some examples are neoplastic |

Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma |

Deep soft tissues, organs (lungs, liver) |

Infiltrative lesion composed of single (not forming capillaries) epithelioid endothelioid cells in chondroid background, sometimes associated with a vessel—looks similar to lobular breast carcinoma in some cases—malignant |

CD34+, CD31+ ERG+, variable keratin expression

Rearrangements in WWTR1-CAMTA1 and YAP-TFE3 |

Kimura disease |

Asians, head and neck region

Associated lymphadenopathy and peripheral blood eosinophilia, elevation in the serum immunoglobulin E, sometimes nephrotic syndrome |

Fibroinflammatory lesion with numerous eosinophils, sometimes eosinophilic microabscesses, vessels inconspicuous |

Typically not required |

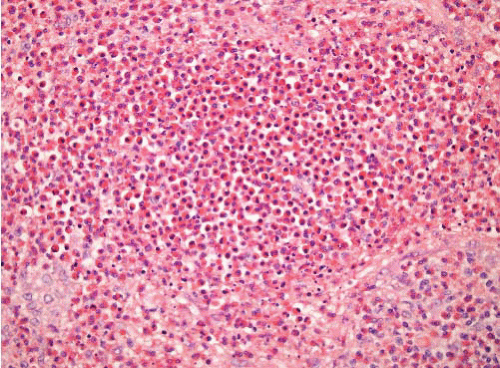

Capillary hemangioma (infantile hemangioendothelioma, juvenile hemangioma, strawberry nevus) |

Newborns and babies, female predominance, head and neck, grow rapidly and then usually regress |

Cellular capillary proliferation with commensurate proliferation of supporting cells (smooth muscle, pericytes) |

GLUT-1+ |

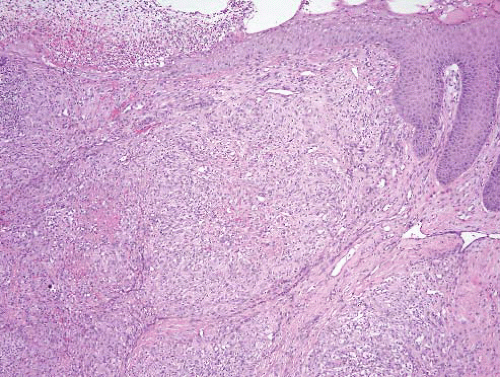

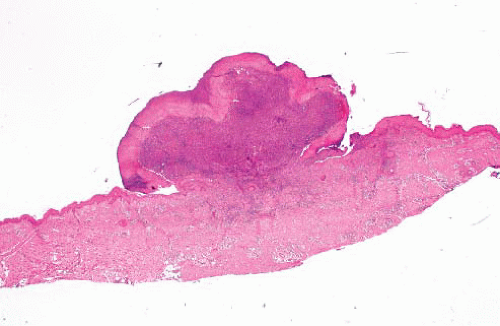

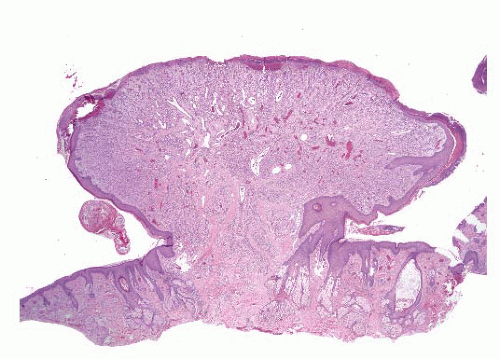

Pyogenic granuloma/lobular capillary hemangioma |

Head and neck of adults, some associated with pregnancy, do not regress |

Lobular capillary proliferation of capillaries, overlying epidermal collarette common |

GLUT-1− |

Cavernous hemangioma |

Any age, usually upper half of body, do not regress |

Gaping blood-filled spaces |

GLUT-1− |

Superficial arteriovenous tumor/malformation |

Perioral region and extremities of adults, small red or purple papules, do not regress |

Well-circumscribed masses of thick- and thin-walled vessels, in dermis (skin) or submucosa (lip)

Some vessels have a “transitional” appearance between arteries and veins |

Typically not required |

Microvenular hemangioma |

Small solitary nodule or plaque involving the extremities of young adults |

Permeative proliferation of small irregularly branching vessels which are well-formed but often have collapsed, somewhat inconspicuous lumina; vessels are thicker than |

Typically not required |

Glomeruloid hemangioma |

Found in patients with POEMS syndrome—polyneuropathy, organomegaly (hepatosplenomegaly and lymphadenopathy), endocrinopathy (amenorrhea, gynecomastia, hypothyroidism, adrenal insufficiency, and glucose intolerance), monoclonal protein (marrow plasmacytosis, paraproteinemia), and skin lesions |

Dilated, ectatic vessels with intraluminal capillary conglomerates, architecturally resembling renal glomeruli |

Typically not required |

Angioblastoma (acquired tufted angioma, progressive capillary hemangioma, angioblastoma of Nakagawa) |

Children and young adults, upper half of body, some painful, do not regress |

Tightly packed clusters of capillaries with a rounded or ovoid (“cannonball”) appearance in a plexiform pattern |

GLUT-1−, CD34+, CD31+, podoplanin (D2-40)+, prox1+, LYVE1+, ERG+ |

Hobnail hemangioma (targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma) |

Solitary lesion, trunk or extremities of young adults

Early examples with central purple, violaceous or brownblack papule, bordered by an inner pale zone and a more peripherally situated ecchymotic ring (“targetoid”) |

Ectatic thin-walled vascular channels situated in the superficial dermis and lined by plump, sometimes epithelioid, endothelium

Deeper vessels, located in the reticular dermis, have an angulated, irregular and slit-like appearance |

Typically not required—endothelial cells CD34+, CD31+, podoplanin (D2-40)−, ERG+ |

Progressive lymphangioma (benign lymphangioendothelioma) |

Head and neck of adults |

Anastomosing vascular channels with a “collagen dissection” pattern |

CD34+, CD31+, podoplanin (D2-40)+, ERG+ |

Angiokeratoma |

Some sporadic; systemic type (angiokeratoma corpus diffusum) is associated with Fabry disease, fucosidosis, and deficiency of beta-galactosidase |

Dilated vessels which are primarily restricted to the uppermost dermis and are bordered or enclosed by elongate rete ridges |

Typically not required |

Verrucous hemangioma |

Reflects superficial extension (into epidermis) of an underlying deep hemangioma or vascular malformation |

Dilated vessels in uppermost dermis enclosed by elongate rete ridges associated with underlying vascular lesion |

Typically not required |

Angioma serpiginosum |

Lower extremities of young women |

Superficial vascular ectasia |

Typically not required |

Cutaneous epithelioid angiomatous nodule |

Blue papules, usually on the trunk of adults |

Circumscribed, unilobular, mainly solid proliferations of large polygonal epithelioid endothelial cells with vesicular nuclei and conspicuous nucleoli and at least focal vasoformation |

Variable staining with CD34, CD31, and FVII-related antigen |

Massive localized lymphedema in the morbidly obese |

Large soft tissue lesions (usually of thigh) with superficial component of longstanding duration in morbidly obese adults |

Dermal fibrosis, expansion of the fibrous septa between fat lobules with increased numbers of stromal fibroblasts, lymphatic proliferation and lymphangiectasia |

Typically not required MDM2, CDK4 both − if performed to exclude liposarcoma |

Well-differentiated liposarcoma |

Deep adipose tissue mass of thighs or retroperitoneum, only rarely involves the subcutaneous fat, no skin changes |

Mature-appearing fat punctuated by enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei, occasionally lipoblasts |

MDM2, CDK4+, nuclear labeling

MDM2 amplification on fluorescence in situ hybridization |

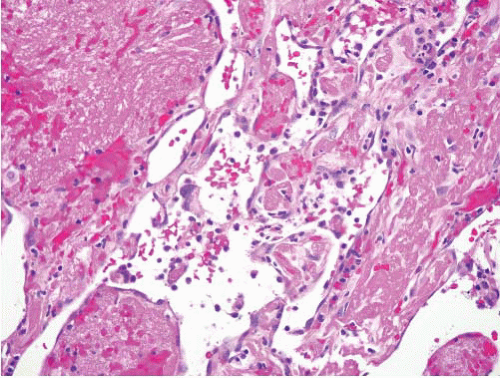

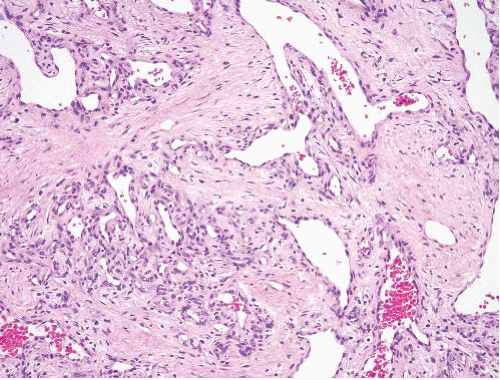

Spindle cell hemangioma |

Slow-growing, often multifocal small painless mass involving the dermis and/or subcutis, usually of hands and feet in young adults

Association with Milroy disease, Maffucci disease, Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome |

Cavernous vascular spaces and a spindle cell proliferation vaguely reminiscent of Kaposi sarcoma |

Typically not required; CD34+ and CD31+ in the endothelial cells of the dilated vessels and interleukin 8+ and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor+ in the spindle cells; IDH1 and IDH2 mutations in cases associated with Maffucci syndrome |

Malignant endovascular papillary angioendothelioma, papillary intralymphatic angioendothelioma, Dabska tumor |

Extremely rare, possibly more common in children but all ages, no favored site |

Intercommunicating vascular channels, epithelioid to columnar endothelium, sometimes arranged in papillary (primitive glomeruloid) tufts with a central avascular hyaline core, intravascular lymphocytes may be prominent |

CD34+, CD31+, podoplanin (D2-40)+ and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-3+ |

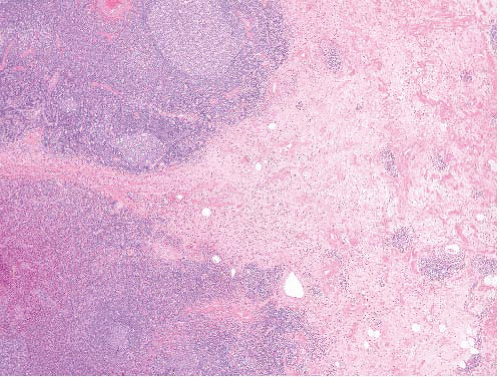

Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma |

Superficial or deep lesion of children (often) and adults (occasional)

In some infants, large retroperitoneal mass associated with a consumptive coagulopathy (Kasabach-Merritt syndrome), aggressive local behavior, association with lymphangiomatosis |

Infiltrative yet lobular growth of well-formed capillaries admixed with short fascicles of spindle cells with slit-like vascular lumina |

Podoplanin D2-40+ in the Kaposi sarcomalike proliferative capillaries but not in the surrounding dilated vessels

Endothelial cells in nodules are CD31+, CD34+, prox1+, LYVE1+, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-3+, FLI1+, but GLUT-1− |

Atypical vascular lesion |

In (usually mammary) skin following radiation

A single or several small papules of patches in the irradiated site

Most benign, but a subset progresses to angiosarcoma, often after several recurrences |

Small (<1 cm) resembling benign lymphangiomas, lymphangioendothelioma, or a lobular capillary proliferation |

CD34+, CD31+, podoplanin (D2-40)+ for lesions that are lymphangioma-like or CD34+, CD31+, podoplanin (D2-40)− for capillary-like lesions |

Retiform hemangioendothelioma |

Rare neoplasms of young adults without gender preference involving skin and subcutaneous tissue, usually of lower extremities

Occasionally metastases to regional lymph nodes but not distant sites |

Narrow arborizing vascular channels lined by plump hobnail endothelial cells with pattern reminiscent of rete testis, often with a striking lymphoid background |

CD31+, CD34+, factor VIII-related antigen+, podoplanin−, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3− |

Composite hemangioendothelioma |

Longstanding dermal and subcutaneous nodules and plaques, usually in the extremities of young adults |

Admixture of benign-appearing well-formed vessels, areas that resemble spindle cell hemangioma, areas similar to retiform hemangioendothelioma, and areas similar to epithelioid hemangioendothelioma |

CD34+, CD31+, factor VIII-related antigen+, podoplanin (D2-40)− |

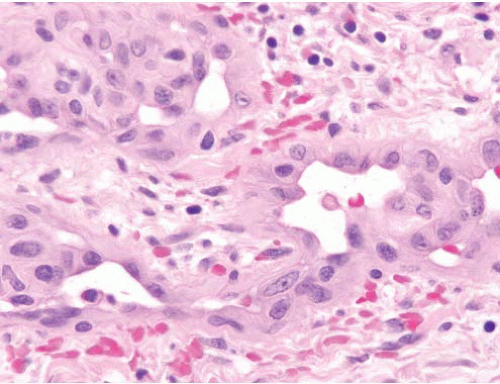

Kaposi sarcoma |

Lesions of immunosuppressed patients or in endemic areas

Tumors can involve skin or viscera |

Spindle cells in fascicles and sheets, extravasated erythrocytes, siderophages, hyaline globules, lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate

Early lesions with more subtle features |

CD34+, CD31+, human herpesvirus 8+, podoplanin (D2-40)+, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3+ |

Superficial angiosarcoma |

Variable tumors (e.g., bruiselike lesions of face and scalp of elderly), associated with lymphedema, postirradiation |

Wide range from hemangiomalike with collagen dissection to overtly malignant epithelioid neoplasms |

Variable staining with CD34, CD31, ERG, podoplanin (D2-40), Fli-1, keratins

Human herpesvirus 8−, Prox1 (limited by lack of specificity) |

Angiomatoid fibrous histiocytoma |

Small lesions usually of proximal limb girdle, trunk, head and neck arising in first two decades, slight female predominance

About 15% recurrences, rare metastases to nodes, rarer systemic metastases |

Multinodular sheets of ovoid cells

Some cases with focal nuclear pleomorphism and multinucleated giant cells, variable hemorrhage, some cases with large cysts lined by tumor cells, not endothelium, variable fibrous and lymphoid cuff |

Desmin+, about 60%, variable calponin+, caldesmon+, SMA−, myogenin−

Negative vascular markers

EWSR1-CREB1, EWSR1-ATF1, FUS-ATF1 |

Aneurysmal fibrous histiocytoma |

Trunk and extremities of adults, cutaneous |

Overlying epidermal hyperplasia, dermal short spindle cells with focal storiform pattern, peripheral thickened collagen bundles and minimal extension into subcutis, variably sized cystic spaces filled with blood but lacking endothelial lining cells, abundant hemosiderin, multinucleated giant cells |

CD34−, CD31−, human herpesvirus 8−, S100 protein−, desmin−, factor XIIIa+ |

Multinucleate cell angiohistiocytoma |

Violaceous erythematous papules of acral regions in middle-aged to elderly women |

Capillaries and small venules of subpapillary plexus and the middermis, in association with angulated multinucleate cells |

Vessels: CD34+, CD31+, podoplanin (D2-40)−

Multinucleate cells: variable CD68 and FXIIIa |