In 2007, suicide was the 11th leading cause of death in the United States, after heart disease, cancer, stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, accidents, Alzheimer’s disease, diabetes mellitus, pneumonia, kidney disease, and sepsis. The suicide rate in the United States is approximately 12 per 100,000. This rate has been relatively steady for more than 40 years, and it falls in the midrange for developed countries. Scandinavia, Japan, Switzerland, Germany, Austria, and countries in Eastern Europe have suicide rates two times that of the United States. Spain, Italy, Ireland, Egypt, and the Netherlands have lower rates (less than 10 per 100,000) (

Sadock & Sadock, 2007;

Sadock, 2009).

Age

Suicide is rare in children. However, it is the third leading cause of death in adolescents aged between 15 and 19 years, following only accidents (first) and homicide (second). In part because teenagers are inclined to do what other teens do, teen suicide, like teen violence, tends to occur in clusters (

Mckeown et al., 1998;

Shafii & Shafii, 2002). In adulthood, suicide risk is positively associated with age and increases substantially after 55 years of age. In the elderly, suicide risk decreases as women age but increases as men age (

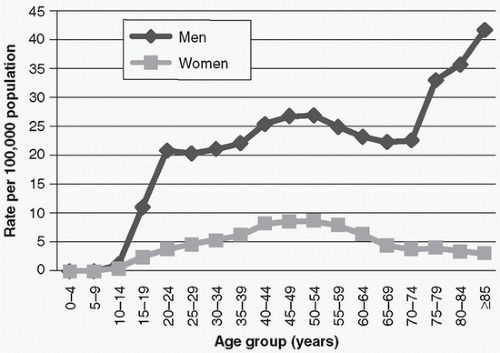

Fig. 14-1); white men 65 years and older are more likely to commit suicide than any other group.

Sex and ethnicity

There are gender and ethnic differences in suicide rates. Although women attempt suicide four times more often than men do, men successfully commit suicide three times more often than women do. One reason for this difference is that men tend to use more violent and hence lethal means than women. Historically, African Americans have had lower suicide rates than white Americans. However, the race gap is narrowing among males aged between 15 and 19 years, particularly for suicide by gun

(

Joe & Kaplan, 2002). Native-American and Inuit groups have high-suicide rates (

Fig. 14-2), and immigrants to the United States have higher rates of suicide than the general population in both this country and their native countries.