Subareolar Duct Excision

Amy C. Degnim

DEFINITION

Subareolar duct excision is defined as the surgical removal of lactiferous ducts in the immediate subareolar space. The terms “major duct excision” or “central duct excision” refer to excision of the entire bundle of ducts contained within the central nipple stalk; microdochectomy refers to selective excision of a single abnormal duct.

ANATOMY

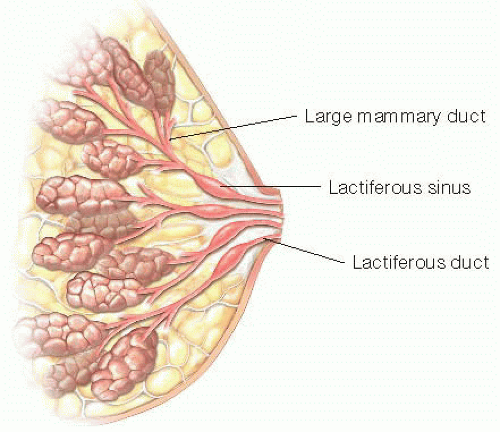

The lactiferous ducts drain converging ducts from lobes of the breast gland and serve as a conduit for milk egress via the nipple during lactation (FIG 1). Most women have approximately 7 to 20 ducts that are distinct and functional sources of milk during lactation. At the base of the nipple, the lactiferous ducts widen centrally in a spindle shape over a short distance. This region is called the lactiferous sinus and can expand in lactation to 8 mm as a reservoir for milk. Surrounding the lactiferous ducts is a system of smooth muscle fibers that contract in response to nipple stimulation and oxytocin release, facilitating milk flow through the nipple.1

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Subareolar duct excision is undertaken in cases of abnormal nipple discharge for two purposes:

To obtain diagnostic biopsy tissue and rule out malignancy

To provide resolution of the bothersome discharge

Abnormal, or “pathologic,” nipple discharge is characterized by the following features:

Discharge from a single duct

Spontaneous discharge

Clear or bloody discharge

The history should be focused on questions to determine the laterality and quality of the discharge as well as whether it is spontaneous or only occurs with manual expression.

Physical exam should include a thorough examination of both breasts and axillae.

In addition, a detailed examination is necessary for both nipple-areolar complexes and the subareolar tissues. Inspect the nipples for crusting, bloodstained ducts, or any visible protuberances or nodules.

The deep tissue of the areolae should be palpated carefully for any small nodules and to determine if subareolar pressure results in nipple discharge.

The nipple itself should be palpated by rolling the nipple between the thumb and forefinger in order to best detect any small nodules located centrally within the nipple stalk. This should be performed first for the breast without discharge to set a normal comparison to the breast that is symptomatic.

If no discharge has been identified up to this step of the examination, then attempt should be made to elicit discharge from both nipples, by applying pressure to the areola at the base of the nipple, then grasping the base of the nipple between the thumb and forefinger and drawing upward with gentle pressure.

Throughout the examination, for any nipple discharge observed, its location (o’clock position) and quality of the fluid should be noted.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

All women with abnormal nipple discharge should undergo diagnostic mammogram and ultrasound. Prior to the imaging studies, the imaging team should be informed about the symptom of nipple discharge and which breast is affected.

Because nipple discharge can be associated with underlying malignancy, the primary purpose of diagnostic imaging is to look for possible signs of malignancy. Another goal of imaging is to evaluate the subareolar tissues for any findings that would explain the presence of nipple discharge.

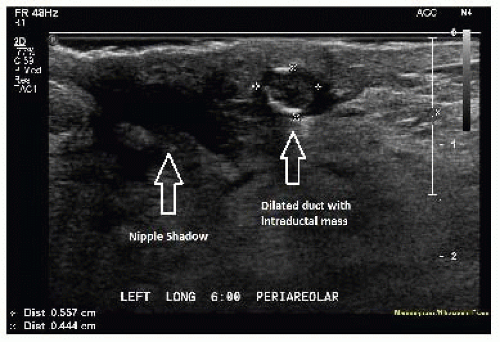

Generally, subareolar ducts are not visible with ultrasound unless they are abnormally dilated. A small nodule visualized within a dilated subareolar duct indicates a likely diagnosis of intraductal papilloma (FIG 2).

Evaluation with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is controversial. It detects more lesions than standard imaging for women with nipple discharge but is imperfect in ruling out malignancy associated with nipple discharge.2

Ductography can be considered as a diagnostic test. This is a radiographic procedure that entails cannulation of the duct with abnormal discharge, then injection of contrast dye with immediate mammographic imaging. This procedure can identify and map out abnormal ducts and identify some intraductal filling defects, but it does not provide diagnostic tissue. For these reasons, it is not a required component of the evaluation and is intentionally avoided in some practices. Although it may help to localize the etiology of the discharge, it cannot reliably exclude malignancy or eliminate need for duct excision.3

Another approach to diagnostic evaluation is via ductoscopy, a microendoscopic procedure to directly visualize the duct(s) with discharge. This requires special equipment and skill, with a learning curve for technical success. Ductoscopy can help to identify lesions and guide excision but has not been proven in large numbers of women to improve diagnosis to the point that duct excision can be avoided.4,5

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Intraductal papilloma

Duct ectasia

Carcinoma, either invasive or ductal carcinoma in situ

Paget’s disease

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Nonoperative management can be considered for cases of nipple discharge when

The discharge occurred on only one occasion and was not reproducible on examination

In this case, 3-month follow-up history and physical examination is recommended.

Alternately, if imaging identifies a benign-appearing lesion and percutaneous core biopsy confirms a benign intraductal papilloma with complete or near complete removal by imaging, then observation is also appropriate with follow-up imaging in 3 months.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Subareolar duct excision removes the lactiferous ducts under the nipple, the primary connection between the nipple and the milk-producing lobules of the breast, so patients must be counseled that lactation from the operated breast should not be possible after surgery.

Selective and focused excision of the single abnormal duct may be performed in an attempt to preserve other ducts for future lactation, but due to the very close proximity of the remaining ducts, scar tissue from the operation may still impair future lactation.

In women who are past childbearing age, a plan to remove the entire bundle of subareolar ducts is preferred because future lactation is not needed, and this approach reduces the chance of recurrent discharge from another duct and need for repeat operation in a field of scar tissue.

The patient should be informed of the possibility of a diagnosis of malignancy yet reassured that benign findings are most likely.

Preoperative Planning

For subareolar mass lesions that are nonpalpable and identified only by imaging, preoperative localization with either a wire or a radioactive seed should be performed to ensure intraoperative guidance to the target.

Before surgery, patients should be counseled that they may experience continued discharge in the first few weeks postoperatively, as postoperative fluid in the subareolar space may discharge via the nipple duct until healing is complete. This should resolve completely by 4 to 6 weeks.

Positioning

The patient should be positioned supine.

The ipsilateral arm is generally positioned at approximately 90 degrees, although the arm could also be tucked based on the patient’s body habitus and preferences of the anesthesia team.

Approach

The general approach is to dissect under the areola toward the nipple, isolate and excise the central duct bundle, and follow any abnormal ducts to complete removal, along with simultaneous excision of any nonpalpable lesions identified on preoperative imaging.

TECHNIQUES

INCISION PLANNING

In general, incisions are placed at the areolar edge.

An incision at the inferior areolar edge is preferred if possible for better cosmesis, especially if the involved duct is located centrally on the nipple surface and the imaging does not demonstrate any abnormalities (FIG 3).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree