Streptococci

Kent B. Crossley

Microorganisms of the genus Streptococcus were a major cause of healthcare-associated infection in the preantibiotic era. During the last half-century, they have been associated with occasional outbreaks of infection in hospitals.

The most frequent streptococcal species encountered as causes of healthcare-associated infections are group A β-hemolytic streptococci (Streptococcus pyogenes) (GABHS), group B β-hemolytic streptococci (Streptococcus agalactiae) (GBS), and Streptococcus pneumoniae. This chapter discusses healthcare-associated infections caused by these microorganisms and by other streptococci (e.g., group C and G streptococci). Healthcare-associated infections caused by enterococci are considered in Chapter 33.

Streptococci were first described in material recovered from wound infections by Billroth in 1874 and 5 years later by Pasteur in the blood of a patient with puerperal sepsis (1). Until the introduction of sulfonamides, streptococci (particularly GABHS) were common causes of healthcareassociated infection. Puerperal sepsis was a major concern in the first third of the 20th century (2). The mortality rate from bacteremic group A streptococcal infections at Boston City Hospital in the 1930s was 72% (3).

Although antimicrobials have markedly reduced the frequency of these infections, streptococci continue to cause healthcare-associated disease. In a recent study of bloodstream infections, 10.3% were caused by Streptococci. S. pneumoniae accounted for half followed by GABHS and viridans Streptococci in decreasing frequency (4).

GROUP A β-HEMOLYTIC STREPTOCOCCI

GABHS are relatively uncommon causes of healthcare-associated infection (5). A review of invasive GABHS infections in Ontario between 1992 and 2000 found that 12.4% were healthcare-associated (6). Surgical site and postpartum infections accounted for two-thirds of these cases. Interestingly, 70% of the hospital outbreaks involved nonsurgical, nonobstetric patients (7). Of severe cases of GABHS disease in Europe in 2003 to 2004, 4.3% were noted to be healthcare-associated (8). GABHS tend to cause small outbreaks of burn wound, puerperal, and neonatal infection that persist and that are difficult to evaluate and control.

GABHS may be serogrouped on the basis of protein antigens, designated as M and T antigens. For the last decade, sequencing of the emm gene, which specifies filamentous M protein, has been more widely used (9). This method has also been used for large population-based studies (10). Random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) and pulse field gel electrophoresis are also occasionally used (11).

Surgical Site Infection and the Epidemiology of GABHS Infection

GABHS are common causes of community-acquired pharyngitis and skin infection. These microorganisms may also be carried in the throat, on the skin, and in the rectum and vagina of asymptomatic people (12, 13, 14 and 15). Some-what <1% of normal individuals have positive anal or vaginal cultures for group A streptococci (14,16). Anal carriage in children with group A β-hemolytic streptococcal pharyngitis appears to be somewhat more frequent; in one study, 6% of children with documented GABHS pharyngitis had the same microorganisms recovered from anal swabs (13).

Wu et al. (12) reported that 12.3% to 18.4% of hospital employees with pharyngitis had throat cultures positive for GABHS. It is curious that, despite frequent carriage of this microorganism in the respiratory tract of healthcare workers, very little healthcare-associated transmission from this source has been documented. Only five small outbreaks of infections appear to be directly the result of pharyngeal carriage of GABHS (17, 18, 19, 20 and 21). In one of these outbreaks, the same strain that infected the patients and an anesthesiologist was also recovered from a member of the physician’s family (17).

Although GABHS may be carried on unbroken skin (15), outbreaks resulting from cutaneous sources in healthcare workers have primarily been traced to individuals with clinically evident infection. Bisno et al. (22) described a patient who developed GABHS bacteremia from an intravascular catheter inserted by a physician who had an identical Streptococcus isolated from a healing wound on the dorsum of his hand. Mastro et al. (23) reported an outbreak of 20 postoperative surgical site infections that occurred over 40 months. This outbreak was eventually traced to an operating room technician who had the identical type of GABHS cultured from psoriatic lesions on his scalp. This individual worked in the operating rooms only before operations were performed.

Asymptomatic rectal or vaginal carriage of GABHS is the most commonly reported source of outbreaks of healthcare-associated surgical site infection. Schaffner et al. (24) described an outbreak that resulted from anal carriage of streptococci by an anesthesiologist. His throat culture was negative, but an M nontypeable group A Streptococcus similar to that recovered from nine patients with infection was cultured from an anal swab. McKee et al. (25) reported an outbreak of 11 cases of infection associated with a medical attendant who was a rectal carrier. The same microorganism was also cultured from two of four family members. In this study, after the carrier exercised in an 8-ft by 11-ft examining room, settle plates yielded GABHS. A similar outbreak involving four patients was reported by Richman et al. (26) and resulted from carriage by a surgeon. Kolmos et al. (21), in a review of surgical site infections causally tied to healthcare workers, noted that anal carriage appeared to be associated with rectal ulcers, hemorrhoids, and other rectal pathology.

Viglionese et al. (27) described an outbreak of postpartum infections traced to an obstetrician who was an anal carrier of GABHS. Of 34 patients delivered vaginally by this physician, 6 (18%) were infected. The obstetrician was treated with penicillin, rifampin, and hexachlorophene; surveillance cultures were negative 1 week, 1 month, and 3 months later. Subsequently, however, four additional cases occurred 14 months after the end of his treatment, and he was again found to be colonized with the same microorganism. One additional case occurred during the next 19 months. This is the only published report that suggests recurrent outbreaks might be caused by one healthcare worker who continues to carry or becomes recolonized with the same GABHS. We have had a similar experience with a vaginal carrier of GABHS. After treatment with erythromycin and rifampin, additional infections occurred, and she was found again to be colonized. Some experts recommend use of settle plates as a sensitive method to assess ongoing shedding of GABHS by carriers during an outbreak (28).

Vaginal carriage has been documented as a source of surgical site infections less often than rectal carriage. Berkelman et al. (29) reported postoperative surgical site infections that occurred on two occasions, 5 months apart, associated with a nurse with both vaginal and rectal carriage of GABHS. (In this case, the two outbreaks involved serologically different streptococci.) Stamm et al. (16) reported another outbreak involving 18 patients. The source was a nurse with vaginal colonization with GABHS.

Based on evidence presented by Berkelman et al. (29) and Mastro et al. (23), it seems most likely that aerosolization of GABHS with motion or activity followed by contamination of the surgical site is the usual mode of transmission. In the outbreaks described by Stamm et al. (16) and Schaffner et al. (24), cases occurred in operating rooms adjacent to the one in which the source employee worked. Rutishauser et al. (30) reported two patients who developed streptococcal toxic shock after exposure to a surgeon who had nasal (but not pharyngeal) GABHS colonization. An outbreak involving three patients (two of whom died) was reported to be associated with a surgeon believed to be colonized with GABHS (31). A recent outbreak of 28 cases of GABHS infection was associated with care from a hospital wound care team. Although vaginal, rectal, and pharyngeal cultures of members of the team were negative, cases recurred a year later and a carrier was then identified (32).

Nearly all of the approximately 20 reported outbreaks of GABHS surgical site infection have been small, relatively chronic, and associated with an infected or colonized healthcare worker who is not immediately identified as the source. Occasional outbreaks not associated with an identified source have been reported. Webster et al. (33) described an outbreak of infection in seven patients on a plastic and maxillofacial surgery ward and in one patient on an adjacent psychiatric ward in London. The source of the outbreak was unclear, and it ended with the closure of the unit before its move to a new building.

GABHS may also be recovered from dust in the environment, and it is possible (but unlikely) that microorganisms disseminated by a carrier could contaminate hands or other surfaces and then be transmitted to a patient.

There are several reported outbreaks in which clusters of healthcare employees have acquired GABHS in an outbreak. Ramage et al. (34) reported three patients and six nurses who had developed infection; the nurses (three of whom were not cultured) all had developed pharyngitis. Kakis et al. (35) described transmission of the identical GABHS strain to 24 healthcare workers. Transmission occurred within 25 hours following exposure to this individual, and all 24 healthcare workers developed symptoms of pharyngitis within 4 days of contact with the source patient.

Two recent reports document transmission from a patient with pneumonia to two nurses (36) and from a patient with necrotizing fasciitis to a respiratory therapist who developed pneumonia and toxic shock syndrome (37). A 2006 report noted transmission from a patient with necrotizing fasciitis to two operating room staff; both developed pharyngitis (38). The last two papers recommended more careful infection control precautions when caring for patients with large open wounds infected with GABHS.

Although a very uncommon event, foodborne GABHS illness may occur. A recent Japanese report described an outbreak among students at a university hospital. After eating boxed lunches, some 65% of the group had GABHS isolated from a throat culture (39).

Burn Wound Infection

GABHS were important pathogens in burn units before the introduction of routine penicillin prophylaxis for patients with thermal injuries. They continue to cause occasional burn wound infections and outbreaks.

In 1984, Whitby et al. (40) reported an outbreak that began in a burn center and eventually spread to involve an intensive care unit in an associated hospital. Of the eight patients in the burn unit who were colonized with GABHS, two developed clinical evidence of infection and one additional patient became bacteremic. The outbreak apparently resulted from admission of a patient who carried GABHS in his pharynx. Burnett et al. (41) described an outbreak involving four patients, six relatives of the index case, and four staff members in Sheffield. The source was a child with burns who had streptococcal pharyngitis. GABHS infection developed in four nurses (cellulitis in two, a facial pustule and an infected whitlow in one each). The outbreak was

controlled by treatment with penicillin V. In the index case, the burn wounds did not clear with oral antibiotic therapy alone but were cured after mupirocin was applied to the burn wounds. The authors believed that the use of shortsleeved isolation gowns was related to the occurrence of the lesions on the forearms of two of the nurses. Allen and Ridgway (42) reported a small outbreak of S. pyogenes infection in a burn unit in Liverpool. The source was apparently GABHS pharyngeal colonization in a patient admitted to the burn unit. The outbreak persisted despite treatment of cases and careful hand washing. Prophylaxis of all uninfected patients on the unit and all new admissions with penicillin V, 500 mg each day, terminated the outbreak.

controlled by treatment with penicillin V. In the index case, the burn wounds did not clear with oral antibiotic therapy alone but were cured after mupirocin was applied to the burn wounds. The authors believed that the use of shortsleeved isolation gowns was related to the occurrence of the lesions on the forearms of two of the nurses. Allen and Ridgway (42) reported a small outbreak of S. pyogenes infection in a burn unit in Liverpool. The source was apparently GABHS pharyngeal colonization in a patient admitted to the burn unit. The outbreak persisted despite treatment of cases and careful hand washing. Prophylaxis of all uninfected patients on the unit and all new admissions with penicillin V, 500 mg each day, terminated the outbreak.

Two papers have questioned the need for prophylaxis of GABHS in patients with burn wound infection. Sheridan et al. compared two cohorts of children (treated in 1992-1994 and 1995-1997, respectively) with and without penicillin prophylaxis (43). There was no difference in the frequency of GABHS infection during the two time periods. Bang and others did a similar study and reached a similar conclusion (44).

Puerperal and Neonatal Infection

The communicable nature of puerperal fever was well understood by 1840 (45,46). The careful observations of Alexander Gordon in Aberdeen and Semmelweis in Vienna made prevention possible (47). Semmelweis noted that an obstetric service staffed by midwives had little puerperal infection. On an adjacent ward, the service run by physicians (who also participated in autopsies on patients who had died) experienced three to five times the number of infections. He also observed that, in hospitals in which obstetric units were distant from autopsy rooms (and here he compared Dublin and Vienna), puerperal infection was uncommon. In May 1847, he introduced chlorine water hand rinses to the first obstetric clinic in Vienna and documented a dramatic decrease in the frequency of puerperal infections (48).

Despite the significant reduction in the occurrence of these infections through hand washing, major outbreaks were relatively common until effective antimicrobials became available (2). Isolated outbreaks of puerperal infection caused by GABHS have continued to occur. Data from the Active Bacterial Core surveillance program from 1995 to 2000 suggest about 220 cases of GABHS postpartum infection occur annually in the United States. Clusters of infections caused by microorganisms of the same emm types suggested common source outbreaks occurred (49). Most outbreaks are small (i.e., one or two cases). While postpartum infections account for only about 2% of invasive GABHS infections in the United States, 3.5% of healthy women with GABHS postpartum infections die of their infection (49).

Van Beneden and others recently assessed knowledge of obstetricians and gynecologists about prevention and management of healthcare-associated GABHS infections (50). Of the respondents, >70% were unaware of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommendations. Most (86%) reported not routinely culturing postpartum infections.

Small outbreaks of infections in newly delivered neonates are also well recognized. Studies published in the last 30 years include an outbreak caused by a tetracyclineresistant strain of GABHS that was isolated from both adults and neonates (51). The outbreak was terminated by closing the implicated ward and administering penicillin prophylaxis or treatment to all of the mothers and infants. Tancer et al. (52) reported an outbreak involving 11 infants, 2 postpartum mothers, 3 nurses, and another hospital employee. This outbreak was temporally related to episodes of pharyngitis in a newly delivered mother and an elevator operator in the maternity wing of the hospital. Neither of these individuals was cultured. Ogden and Amstey (53) described five patients with puerperal GABHS infection. These cases were characteristic of the clinical presentation of puerperal GABHS infection. All of the mothers experienced uterine tenderness and then developed fever spikes associated with recovery of these microorganisms from the lochia. McGregor et al. (54) reported a similarsized outbreak. A labor room nurse had mild eczema on her hands, and these lesions grew GABHS and Staphylococcus aureus. The microorganism was serologically identical to that recovered from the patients. In two studies, evidence has suggested that outbreaks were related to contamination of inanimate objects. In one, a handheld showerhead was seen as a possible route of transmission; in the other, use of a communal bidet was implicated (55,56). GABHS were shown by Claesson and Claesson (55) to remain viable on a metal surface for more than 9 days.

Outbreaks of GABHS infection also have involved neonates. In these episodes, microorganisms have primarily contaminated the umbilicus. Transmission between infants has apparently occurred with nursing care. In the two outbreaks described by Geil et al. (57), penicillin was administered to all of the infants in the nursery on both occasions. This regimen was successful in the first of their two outbreaks. However, in the second outbreak, it was not successful without the additional application of bacitracin ointment to the umbilical stumps of the infants. Bygdeman et al. (58) reported an outbreak in Stockholm in which 67% of infants had umbilical colonization with GABHS. Pharyngitis was documented among family members of neonates. Five of sixty-nine mothers who had nose and throat cultures for GABHS yielded this microorganism. Presumably, this outbreak resulted from introduction of an epidemiologically virulent strain by a mother or healthcare worker. Transmission at the time of delivery could also have been responsible, although the authors did not perform vaginal or rectal cultures.

An outbreak described by Isenberg et al. (59) involved 10 newborn infants over a 2-month period. Nineteen percent of the infants in the nursery were found to be carriers of streptococci. Again, umbilical infection was most frequent. Only 1 of the 10 infected infants had GABHS isolated from throat cultures.

Infections Associated with Nursing Homes

GABHS has been reported to cause outbreaks of infection in various healthcare settings notably in facilities for the elderly (60, 61 and 62). Over the last 20 years, a number of outbreaks of GABHS infections have been reported in long-term care units (LTCF) in the United States. These reports have occurred during a period in which GABHS disease has been caused by strains of apparent increasing virulence (63,64).

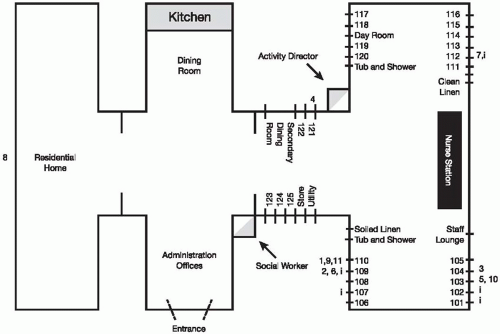

The CDC described outbreaks in four nursing homes during the winter of 1989 to 1990, each in a different state (65). Infection occurred in 18 residents, with slightly over half [(10 of 18 (56%)] of the residents dying. Pneumonia and cutaneous infection were most common. Culture surveys to identify pharyngeal carriage in each of the four nursing homes revealed that 11 of 312 residents (3.5%) and 4 of 297 staff members (1%) had asymptomatic pharyngeal carriage of GABHS. These isolates were found to be the same serotype as the strains causing infection in each of the homes. The outbreaks were controlled following antimicrobial prophylaxis or therapy (Fig. 32-1).

Data about long-term care facility (LTCF) associated GABHS infection from the Active Bacterial Core surveillance program from 1998 to 2003 were recently reviewed (66). Invasive GABHS infections were six times more common among LTCF residents when compared with community-living elderly. Death was also 1.5 times more frequent among the LTCF residents. Bacteremia without a focus, pneumonia, and cellulitis were the most common infections in both groups of patients.

A review of invasive GABHS infection in Minnesota for the years 1995 to 2006 found that 7% of cases occurred in nursing home residents. Of the 134 cases, 34 were part of 13 clusters of infection (67). In two of these outbreaks, 2.7% and 6.2% of throat cultures from staff grew GABHS. In the same facilities, 5.9% and 4.5% of throat cultures of residents were positive. Carriage rates documented in a Georgia outbreak were 9% among staff and 10% among residents (68).

A more recent LTCF outbreak in Georgia involved six cases that occurred in a 104-bed facility in March and April 2004. As also documented in the other Georgia outbreak, presence of nonintact skin was associated with this cluster. Although 16.5% of residents carried the implicated strain, only 2.4% of employees were colonized with this microorganism. These authors suggested the importance of training both employees and visitors in hand hygiene and infection control (69).

Another outbreak occurred in a Nevada nursing home in late 2003 (70). The authors reported that about a third of employees did not always wash their hands between patient contacts.

Schwartz and Ussery (71) reviewed reports to the CDC of invasive GABHS infections in nursing homes and described five other outbreaks that were primarily associated with noninvasive infection. Outbreaks of noninvasive disease tended to last longer, were associated with more cases, and characteristically involved patients who were more physically impaired than those infected in the invasive outbreaks.

In all of these nursing home outbreaks, there was no clear proof that healthcare workers were sources of the microorganism. (The positive pharyngeal cultures suggest possible introduction of these microorganisms, but obviously the healthcare workers might have been colonized by exposure to the nursing home patients.) In two of the nursing home outbreaks investigated by the CDC, extensive environmental culturing yielded only one positive culture for GABHS. This would suggest that these microorganisms are uncommonly transmitted by fomites (65).

Critical Care Units

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree