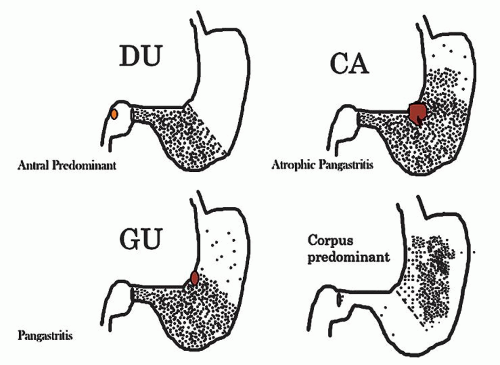

Gastritis (in its broadest sense) and its complications account for millions of doctors’ office visits each year. Symptoms are often associated with acute changes or complications described as mild upper abdominal discomfort, indigestion, heartburn, coated tongue, foul breath, and bad taste to more ominous symptoms such as loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting blood or coffee-ground material, diarrhea, and dark stools. Most patients with chronic gastritis have no symptoms. Even so, these symptoms are not specific and include broad differentials such as

H. pylori infection, other infections, bile reflux, inflammatory

bowel disease (IBD), and side effects of medications (

Table 13-4). As treatment depends on the cause, it is important to know the cause for appropriate management. Occasionally, it may be necessary to list possible etiologies for gastric inflammation, rather that reporting “nonspecific chronic inflammation”—which is an unnecessarily complex term as all inflammation is “nonspecific,” so these words can always be omitted from reports without deleterious effect. If it is specific, the cause (e.g.,

Helicobacter) should be stated.

Reactive (Predominant Epithelial) Changes

Reactive (chemical/reflux-associated) gastropathy is a reaction to noninfectious irritants. This can be due to protracted exposure to bile and pancreatic juice (especially postgastric surgery

14). The most infamous of irritants are NSAIDs, which include over-the-counter drugs such as aspirin and ibuprofen, and many prescription medicines. Other medications— such as bisphosphonates used for osteopenia, iron pills and irritants in food such as capsaicin in peppers and chilies and alcohol—can all cause this lesion.

15 These irritants usually cause no clinical problems when taken for the short term, although endoscopic damage can be seen even with short-term use. However, regular (or excessive) use can lead to a more severe gastropathy as well as erosions and ulcers. With the increasing use of aspirin and other NSAIDs, and decreasing prevalence of

Helicobacter, chemical/reactive gastropathy is increasingly seen in gastric biopsies, and may co-exist. Anti-platelet mediations also cause similar injury.

Pathogenesis: Aspirin is the best-studied NSAID, the mechanism of injury is inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis by inhibiting cyclooxygenase (COX) 1 and 2.

16 Aspirin also changes the ability of the mucosa to maintain a pH gradient causing gastric acid back-diffusion with resultant mucosal injury.

16 Further, its anticoagulant properties increase the risk of bleeding once erosions or ulcers are present. Conversely, some other NSAIDs have antiplatelet properties but do not possess this therapeutic anticoagulant effect. NSAIDs produce mucosal injury by both local and systemic effects.

16 Newer NSAIDs are predominantly COX-2 inhibitors, which make them less likely to cause gastric injury and the risk of gastric (or duodenal) injury is reduced, but not abolished. A variety of antiplatelet medications are increasingly being implicated causing similar injury.

Histology: The histology of reactive gastropathies has both an acute and a chronic phase, although

in practice it is often reported without qualifying it as acute or chronic. In some patients both are present together.

Reactive gastropathy. The morphologic changes that accompany ingestion of medications such as NSAIDs have been known for decades, 15 but they are now more commonly recognized.

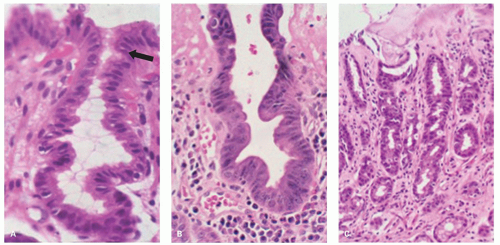

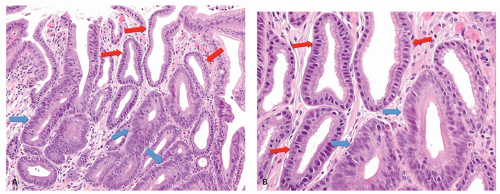

In the acute phase, as in any reparative process, the main changes are

1. Mucin depletion—the amount of supranuclear mucin is markedly reduced or absent, so that at low power the cells appear more basophilic—often the most apparent low-power indication that this change is present

2. A reduction of the normal cell size so that the cells are frequently low columnar to cuboidal

3. A corresponding increase in nuclear size, and also an increase in hyperchromatism; nuclei that are normally compressed at the cell base markedly increase in size, and in conjunction with the smaller cell size cause a marked increase in nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio.

4. Because this appears to be a reparative, partly restitutional process, the number of cells and nuclei appears reduced; this results in nuclei being distinct and separated, one of the best indicators that this is not dysplasia. However, especially following erosions, the reactive changes can be more marked so that the nuclei become more open and vesicular with distinct nucleoli, and there may also be concomitant increase in nuclear hyperchromatism (

Fig. 13-3).

5. Changes are usually most marked in the mucous neck region, and tend to decrease superficially. Interestingly, some of these changes appear on the surface, especially the mucin depletion, but most of the other changes are maximal in the mucous neck region suggesting that these are all a reaction to injury and not dysplasia. These changes can be easily missed in the fundic glands as the foveolae are shorter and changes can be mistaken for biopsy artifacts. Occasionally, the changes may extend deeper to involve the entire length of the oxyntic or antral glands (

Fig. 13-3E).

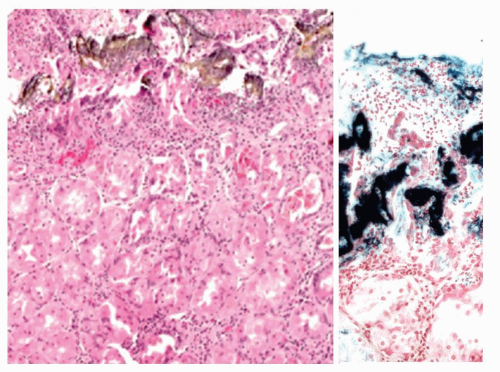

6. Erosions or ulcers may be present. When this occurs, careful examination of the erosion or ulcer base should be carried out for the presence of crystals or foreign material representing medications. Iron encrustation can readily be confirmed using Perl’s stain (

Fig. 13-3). When erosions or ulcers occur, the immediately adjacent epithelium may be

restituting, and appears attenuated as seen in any restitutional processes.

7. Occasionally there is focal edema in the lamina propria, which may also be devoid of inflammatory cells or have a predominantly acute or eosinophilic (sometimes both) infiltrate. A sparse chronic inflammatory infiltrate can also be seen, but in most biopsies chronic inflammation is usually conspicuous by its absence or minimal presence (

Fig. 13-3), indicating that

Helicobacter infection is not the etiology of the changes present.

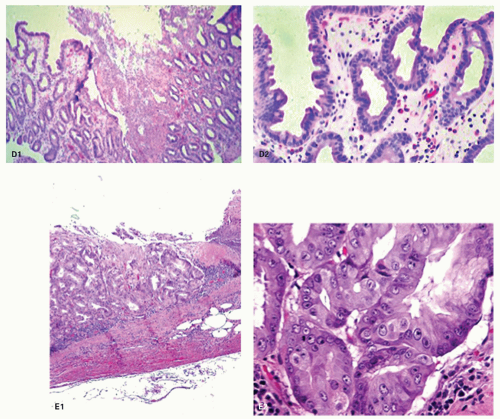

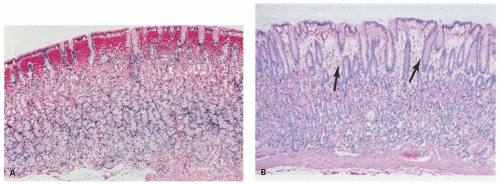

In the chronic phase, other changes become apparent. Sometimes the acute and chronic phases coexist, sometimes only the chronic changes persist, and it is presumed that they followed the acute changes (

Fig. 13-4).

1. Foveolar hyperplasia can develop that results in tortuosity of pits in the mucous neck region.

2. Proliferation of smooth muscle in the lamina propria above that normally seen

3. A degree of vasodilatation of capillaries with congestion and edema

17,

18

4. If erosions have occurred, a degree of lamina propria fibrosis ensues.

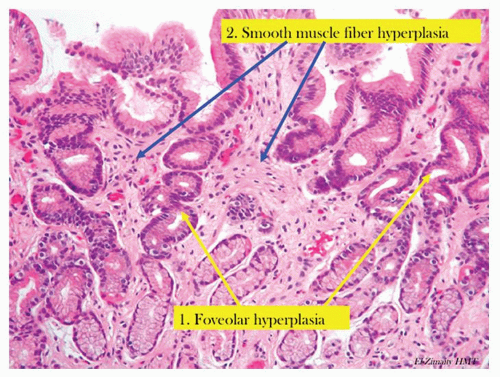

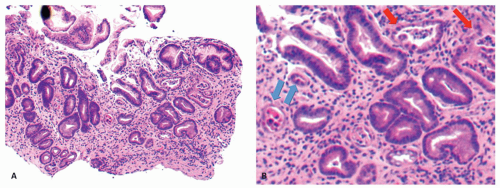

Iron toxicity, especially in children, may result in gastric mucosal necrosis, sometimes with extension into the submucosa.

19 The encrustation is often visible (

Fig. 13-5).

Biopsies show reactive mucosal changes (mucin depletion, foveolar hyperplasia, and smooth muscle hyperplasia) without the severe inflammatory component seen in infectious gastritis (

Fig. 13-5).

Foveolar hyperplasia appears to be a result of excessive cell exfoliation from the surface epithelium over a period of time and, accordingly, is likely to be seen in all types of active gastritis.

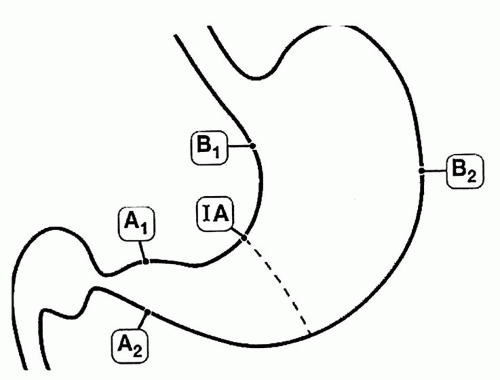

17 Further, if the insult is ongoing, superimposed changes of acute reactive gastropathy may also be present, and this may include erosions. These histopathologic changes are not seen in all patients and when present are usually patchy (postgastrectomy states usually being more diffuse and therefore the exception). Pathology is more likely to be seen in biopsies obtained from incisura angularis.

20 If biopsies are taken, then those from areas of endoscopic abnormality are preferred.

Gastric glands may be distorted and dilated, with an absence or paucity of plasma cells. In some areas there is no gland distortion, just simple thinning of the mucosa.

21 Other features include stomal erosions,

22 lipid islands, and intramucosal cysts

21 (

Fig. 13-6). Sometimes the cysts become large enough to be visible grossly and extend into the submucosa. These cysts have been labeled with a variety of names, including

gastritis cystica polyposa and

gastritis cystica profunda.

23 Adenocarcinoma in the postoperative stomach has been reported in association with these cysts, but this association appears to be coincidental, especially because the cysts are so commonly found microscopically in the postoperative stomach.

21,

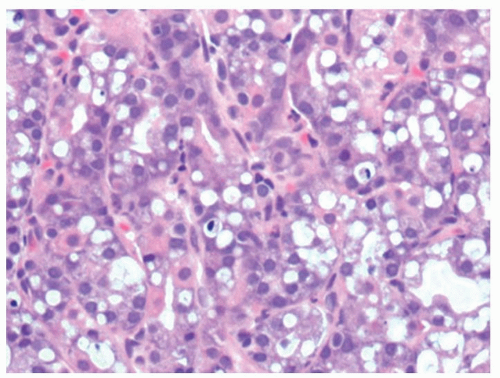

24Toxic gastropathy. Changes can be seen characterized by vacuolated cells in the specialized mucosa. The cause is not always apparent but may be prominent in uremic patients, the vacuolation tending to occur in chief cells rather than PCs (

Fig. 13-7).

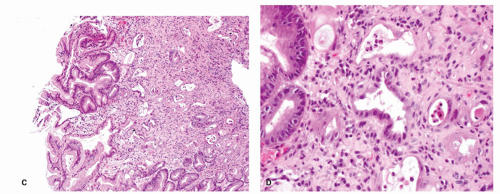

Distinction of Reactive Changes from Dysplasia

It is imperative to distinguish reactive changes from dysplasia as they resolve when the acute insult is withdrawn. The most helpful feature is that at the surface there is invariably maturation in the form of

small mucin droplets at the surface. While “bottom-up” dysplasia (dysplasia maximal in the pit bases) does occur, it is quite rare, so the diagnosis of dysplasia should only be made if the diagnosis is absolutely clear, and ideally conforms to one of the usual forms of foveolar dysplasia (see following chapter). The adage that dysplasia should never be diagnosed in the presence of overlying or adjacent ulcers, erosions, or restituting epithelium unless absolutely clear is a good one. Making a diagnosis of dysplasia under these circumstances is fraught with danger. Unless there is absolutely no diagnostic uncertainty, it is usually best to rebiopsy the area following antisecretory therapy (e.g., PPIs) to ensure that the changes persist when the erosions have healed. Fortunately, even if dysplasia is diagnosed and graded, most can be visualized and treated endoscopically (

Fig. 13-8).

Reactive gastropathy may be confused with dysplasia and may be one reason why some have reported large numbers of cases of dysplasia in the postoperative stomach.

21 We suspect that the vast majority of these changes represent “regenerative atypia” rather than dysplasia. Highly reactive cytologic changes are seen in other conditions, such as in the mucosa

adjacent to alcohol- and NSAID-induced erosions

27 in some patients without erosions on NSAIDs

17 and in the mucosa at or near-healed gastric ulcer sites. Though, at times, it can be challenging, atypical reparative changes can be distinguished from dysplasia (intraepithelial neoplasia or dysplasia) as discussed in the previous section.

Reactive changes in intestinal metaplasia. It should also be recognized that gastric intestinal metaplasia, whether incomplete (residual foveolar epithelium admixed with goblet cells) or complete (goblet and absorptive cells with or without Paneth cells), can be subject to surface injury and reactive changes. However, the same principles apply regarding using surface maturation as an indicator of reactive changes and not diagnosing it in the presence of ulcers, erosions, or restituting epithelium. These can also be recognized by the presence of metaplasia in the adjacent mucosa. However, complete intestinal metaplasia starts with intestinal nuclei that are already considerably larger than native gastric mucosa. Nuclei in incomplete intestinal metaplasia are more open and vesicular with distinct small nucleoli. Reactive changes enhance all of these features, so this needs to be taken into account. All forms of reactive mucosa have both mucin depletion and enlarged pleomorphic nuclei occupying most of the cell, and may be accompanied by erosions or ulcer. The tip-off is the presence of (a) restituting mucosa (low cuboidal or columnar) with nuclei that are usually more widely separated than in normal mucosa, especially superficially, and (b) usually a degree of maturation superficially, to the degree that a diagnosis of dysplasia should be made very cautiously in the presence of active restitution. It is worthwhile to remember that in the bases of these pits, nuclei can overlap and be stratified and hyperchromatic causing confusion with adenoma/dysplasia.

Reporting reactive gastropathy: Minor degrees of superficial mucin depletion are relatively common, and it is unclear how much surface mucin depletion is required to report the changes, or indeed whether they can be seen physiologically. As a guide we do not report reactive changes unless the mucin droplet in the superficial epithelial cells (usually about 75%-80% of the cell) is <50%, but there are no data to support this. However, when reported we usually indicate the most common causes.

Reporting chronic changes: Usually mild chronic reactive changes alone, such as isolated foveolar hyperplasia, are not reported unless marked, as they

tend to refer to events that happened at some point in the past, and it is unclear how long these changes take to reverse. If accompanied by acute changes of damage, then “reactive changes” covers both acute and chronic changes without the need to specify.

Clinical Implications: Of the millions of patients who every day ingest NSAIDs/ASA, only about 2% per year develop a GI complication severe enough to require medical attention, usually a bleeding gastric ulcer. Yet even 2% of a million is 20,000 events. It is possible that these patients represent a subset of individuals with a predisposition (increased sensitivity) to greater loss of their physiologic mucosal defense mechanisms. The risk of GI bleeding with NSAID use increases with age, duration of use, comorbidities, anticoagulant use (including aspirin that may also cause the damage itself), and a history of bleeding ulcers. However, it also causes bleeding in infants.

28 A subset of patients (about one-third in one series

20) may suffer a modest mucosal injury that results in one of the characteristic chronic changes of reactive gastropathy. However, in a series looking at the protective use of PPIs on naproxen 500 mg b.i.d.,

4 within a week 25% developed antral ulcers, 12.5% duodenal ulcers, and 9.4% ulcers in multiple locations (one developed ulcers in the antrum and body; two in the antrum and duodenum). Of those taking PPIs, only 11.8% developed ulcers, all of which were antral. Anecdotally we have seen inflammatory masses in the cardia and proximal duodenal that seem likely NSAID related. They may take weeks/months to resolve or persist for months.

The gastric mucosa of the majority of users may therefore never develop changes that can be detected by endoscopic or histopathologic examination. In practice, however, most NSAID users have been taking them for long periods of time, and it is less clear how well the stomach is able to adapt to chronic NSAID ingestion. Overall, only a small subset of chronic NSAID users have biopsies with all features we commonly associate with chemical gastropathy; most may only have foveolar hyperplasia.

20 In addition, such changes may occasionally occur in persons with no history of chemical injury. Concurrent

H. pylori infection makes a firm diagnosis of chemical gastropathy extremely arduous.

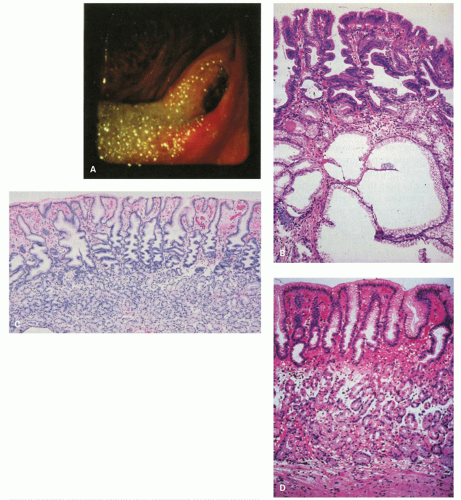

20Alcoholic gastropathy. The term

alcoholic gastritis (or gastropathy) is commonly used in a clinical or endoscopic context to explain abdominal pain or gastric lesions in alcoholic patients. Gastric hemorrhages, erosions, or both are found in 20% or less of actively drinking alcoholics with GI bleeding

27 (

Fig. 13-9A). In humans, there are few data concerning the histologic basis of gastric erosions or subepithelial (lamina propria, rarely with submucosal) hemorrhages. However, in 1954 (pre-

Helicobacter days), servicemen had their gastric mucosa examined after acute alcoholic ingestion.

29 In most, a variety of lesions were noted: patchy hyperemia, erosions, petechiae, and “exudate.” Biopsy specimens showed mainly superficial gastritis with prominent neutrophils.

29 Some specimens exhibited edema of the foveolar region. More recently, actively drinking alcoholics had biopsy specimens taken from either subepithelial (lamina propria) hemorrhages or erosions, with specimens for comparison from adjacent sites.

27 The subepithelial hemorrhage specimens revealed foveolar region hemorrhage in target lesions and sometimes striking edema in the adjacent mucosa (

Fig. 13-9B). The erosions were verified histologically in 70% and commonly exhibited a pseudomembranous appearance. In both the erosions and the hemorrhages, the associated inflammatory change

was mild and was similar in severity in the lesions and the adjacent mucosa. In actively drinking alcoholic patients, the gastric mucosa may, in addition, exhibit the features of

congestive gastropathy if there is portal hypertension. This is discussed in the next section.

Caustic-induced injury. Accidental or suicidal ingestion of acids or alkalis (commonly in the form of household cleaners) may cause a wide range of oral, esophageal, and gastric lesions.

30,

31 The gastric antrum is especially vulnerable, with lesions ranging from superficial erosions to gangrene. A late complication in some cases is the development of gastric antral strictures.31

Graft versus host disease. is discussed in detail in

Chapter 3. GVHD is seen in severely immunosuppressed patients after allogeneic bone marrow transplant where the donor T cells attack host cells leading to cell necrosis. Upper endoscopic examination in the context of suspected or proven GVHD is done if upper GI symptoms are prominent. The severity of change in the upper gastrointestinal tract (UGT) frequently do not parallel the colonic changes (see

Chapter 3). The endoscopic spectrum ranges from normal to subtle swelling to erosions, ulcers, and mucosal sloughing. In addition to mild reactive changes, variable degrees of epithelial injury are seen in a background of few inflammatory cells. In general, the histopathology is that of epithelial injury/death at variance with the amount of inflammation present. In the acute phase, epithelial injury can be seen as increased apoptosis (occasionally more numerous in the neck area), attenuated regenerative-appearing epithelial cells in less injured glands, granular eosinophilic debris intermixed occasionally with nuclear debris within dilated glands, sloughed mucosa, and total destruction of gastric glands in severely injured glands. The histopathology in chronic cases can include crypt loss, inflammatory polyps in severe disease, and architectural distortion with crypt branching and atrophy.

32,

33,

34 Telangiectatic vessels suggestive of gastric vascular ectasia have been identified.

34 Biopsy specimens are commonly taken to also rule out infections such as cytomegalovirus (CMV). Nonetheless, similar histopathology can be seen in CMV and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, transplant recipients, and in primary immunodeficiency.

34

Chemotherapy and radiation. can cause both gastritis and stomach ulcers. The pathology is similar to that seen in chemical/reactive gastropathy with glandular atypia and increased apoptosis (apoptotic gastropathy), and there may be abnormal mitosis.

35 A typical feature, identifiable at low power, is that adjacent pits with relatively normal epithelium, and pits with attenuated mucosa, and all stages between, can be immediately adjacent to each other (

Fig. 13-10). Gastric injury induced in short-term exposure is often temporary. The acute response to massive irradiation occurs largely in the antrum and the prepyloric region. Not uncommonly, gastric erosions or discrete ulcers are encountered in patients with malignancy who have received abdominal irradiation and are on chemotherapy. Biopsy specimens and cultures may be obtained to rule out recurrent or metastatic disease and opportunistic infection. With larger doses, the damage may be irreversible with destruction of acidproducing glands.

Ischemia. Ischemic disease of the stomach is extremely rare. See

Chapter 2 for a more detailed discussion. Atheromatous embolization of cholesterol,

36 therapeutic

embolization to help control bleeding, accidental entry of selective intra-arterial radiotherapy (SIRT) beads, and vasculitis

37,

38 or hypovolemic states are reported causes of erosive gastritis and gastric ulcers. There have also been isolated reports of patients with chronic gastric ulcers and erosions that healed after intestinal revascularization.

39 The reported histology in these cases may lack the classic features of ischemia. In severe disease, epithelial and glandular cells are shed in the lumens of pits. Although this sounds innocuous, the mucous-producing cells can take on the appearances of signet ring cells, mimicking signet ring carcinoma (

Fig. 13-11), analogous to similar lesions seen in pseudomembranous colitis. Another potential mimic of signet ring cells are the normal mucous-producing cells that appear in the oxyntic mucosa as it approaches the antrum. The polarity of these cells may appear abnormal, but these are terminally differentiated cells with no proliferative activity (

Fig. 13-11E,F), while parietal cells can be shed into the lumen in oxyntic mucosa and raise the question of parietal cell carcinoma because of apparent disorderly sheets of cells (

Fig. 13-12). The gastroduodenal subepithelial hemorrhages and erosions reported in some children with

Henoch-Schonlein purpura might be due to vasculitis-induced mucosal ischemia.

40