Splenectomy and Splenorrhaphy

Total splenectomy is performed for hematologic indications and for traumatic injury. Special techniques for repairing the injured spleen are discussed in Figures 70.8 and 70.9. A staging laparotomy procedure for Hodgkin disease is discussed in Figure 70.10. Laparoscopic splenectomy, an increasingly attractive alternative for elective splenectomy, is described in Chapter 71.

SCORE™, the Surgical Council on Resident Education, classified open splenectomy as an “ESSENTIAL COMMON” procedure and splenorrhaphy as an “ESSENTIAL UNCOMMON” procedure.

STEPS IN PROCEDURE—SPLENECTOMY

Left subcostal, upper left paramedian, or upper midline incision

Early Ligation of Splenic Artery (Optional)

Divide gastrocolic omentum and enter lesser sac

Identify splenic artery and ligate

Incise peritoneum lateral to spleen and gently develop the plane deep to spleen and tail of pancreas

Divide attachments to splenic flexure of colon and short gastric vessels

Identify tail of pancreas and protect it from harm

Ligate and divide splenic artery and vein and remove spleen

Check hemostasis; seek accessory spleens

Close abdomen without drainage

HALLMARK ANATOMIC COMPLICATIONS—SPLENECTOMY

Injury to tail of pancreas

Injury to stomach

Injury to colon

Missed accessory spleen

LIST OF STRUCTURES

Spleen

Splenic artery

Splenic vein

Stomach

Short gastric vessels

Left gastroepiploic artery

Transverse mesocolon

Celiac nodes

Hepatoduodenal nodes

Para-aortic nodes

Iliac nodes

Mesenteric nodes

Pancreas

Gastrosplenic ligament

Gastrocolic ligament

Splenorenal ligament

Lesser sac (omental bursa)

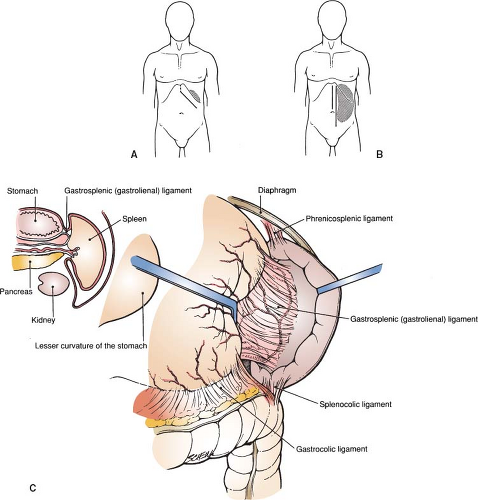

Splenic Exploration and Assessment of Mobility (Fig. 70.1)

Technical Points

Position the patient supine on the operating table. If the spleen is small, place a folded sheet under the left costal margin to elevate the operative field. A left subcostal incision (Fig. 70.1A) provides the best exposure for a small- or normal-sized spleen. However, this incision divides muscles and may result in wound hematoma in patients with profound thrombocytopenia. As the spleen enlarges, it descends from the left upper quadrant, displacing the hilar vascular structures medially. Thus, in a patient with an enlarged spleen, use a midline or left paramedian incision for splenic exposure (Fig. 70.1B).

Explore the abdomen. Pass your nondominant hand up over the spleen and assess its mobility and size, as well as the nature and location of the attachments to the diaphragm and retroperitoneum.

At this point, decide whether or not to proceed with preliminary ligation of the splenic artery in the lesser sac. This maneuver decreases splenic blood flow and should be considered in the patient with a large spleen, particularly when difficulty in mobilization is anticipated.

Anatomic Points

The spleen develops embryologically in the dorsal mesogastrium. As the stomach rotates, the greater omentum develops as an elongation and subsequent redundancy of the dorsal mesogastrium. The pancreas (also initially within the dorsal mesogastrium) becomes retroduodenal. The spleen comes to lie in the left hypochondriac region, interposed between the diaphragm and the left kidney posteriorly and the fundus of the stomach anteriorly. Unlike the pancreas, it does not become retroperitoneal, but instead retains its intraperitoneal status, at the left extremity of the lesser sacromental bursa.

Short bilaminar peritoneal folds attach the spleen to the fundus of the stomach (gastrosplenic or gastrolienal ligament)

and to the left kidney and diaphragm (splenorenal or phrenicosplenic ligament) (Fig. 70.1C). The gastrosplenic ligament is really the left extremity of the gastrocolic ligament; thus, there is also a splenocolic ligament. The splenorenal ligament is the left extremity of the transverse mesocolon. The attachments of spleen to colon are avascular.

and to the left kidney and diaphragm (splenorenal or phrenicosplenic ligament) (Fig. 70.1C). The gastrosplenic ligament is really the left extremity of the gastrocolic ligament; thus, there is also a splenocolic ligament. The splenorenal ligament is the left extremity of the transverse mesocolon. The attachments of spleen to colon are avascular.

The sides of these ligaments (gastrosplenic and splenorenal) that contribute to the walls of the lesser sac are continuous at the hilum, whereas the sides that are part of the boundary of the general peritoneal cavity are separated by the visceral peritoneal investment of the spleen. In other words, the spleen is invested with the general peritoneal layer of the embryologic dorsal mesogastrium. Both gastrosplenic and splenorenal ligaments are vascular. The splenorenal ligament supports the splenic artery and vein (and their splenic ramifications), whereas the gastrosplenic ligament supports those branches of the splenic artery (and the accompanying veins)—namely, the left gastroepiploic artery and short gastric arteries—that supply the greater curvature and fundus of the stomach.

The left gastroepiploic artery may originate from one of the splenic branches, rather than from the splenic artery proper. The short gastric arteries, of which there are typically four to six, can arise from the left gastroepiploic artery, the splenic artery proper, the splenic branches of the splenic artery, or any combination thereof.

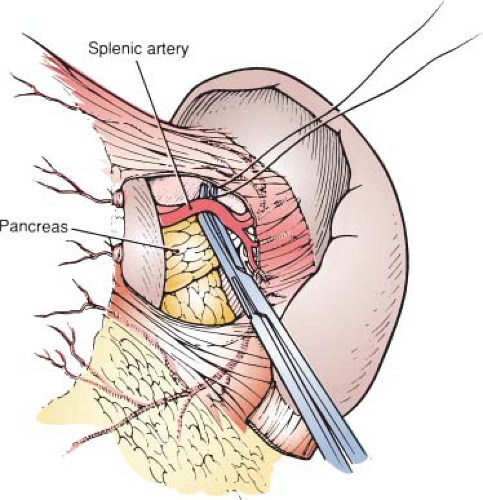

Ligation of the Splenic Artery in the Lesser Sac (Fig. 70.2)

Technical Points

Enter the lesser sac by dividing the gastrocolic omentum. Serially clamp and ligate multiple branches of the gastroepiploic artery and vein until you have created a window in the gastrocolic omentum that is of sufficient size to admit retractors. Elevate the stomach, dividing the filmy avascular gastropancreatic folds as necessary to expose the pancreas. Identify the splenic artery where it loops along the upper border of the pancreas and pass a right-angle clamp under it. Ligate the splenic artery with a heavy silk tie.

Anatomic Points

Make the gastrocolic window either between the stomach and gastroepiploic arcade or between the gastroepiploic arcade and colon. Nothing will be devascularized in either case owing to the free and abundant anastomoses in this area. After entering the lesser sac (omental bursa), observe the pancreas through the parietal peritoneum of the posterior wall of the lesser sac. The characteristic corkscrew course of the large splenic artery (which is about 5 mm in diameter) along the superior border of the pancreas is related to age. The tortuosity is maximal in the elderly, minimal in the young, and absent in infants and children. This tortuosity lifts the splenic artery up out of the retroperitoneum behind the pancreas. In a child, it may be necessary to incise the peritoneum carefully and elevate the superior border of the pancreas to find the splenic artery. The splenic vein is not invested in a common sheath with the artery. Instead, it is somewhat inferior, always retropancreatic, and never tortuous.

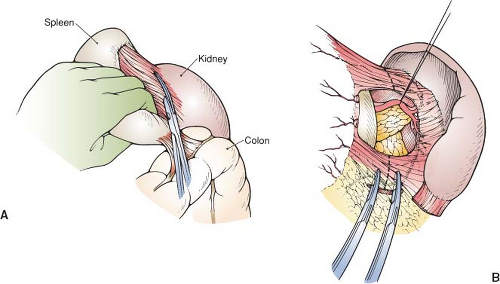

Mobilization of the Spleen (Fig. 70.3)

Technical Points

Place retractors on the left costal margin. Pass your nondominant hand up over the spleen and hook the posterior edge, pulling the spleen down strongly and rolling it medially. Use a laparotomy pad over the spleen to improve traction. By strong compression of the spleen and steady traction, coupled with good retraction up on the costal margin, one can create a space in which to work.

Incise the peritoneum lateral to the spleen (Fig. 70.3A). Pass your nondominant hand under the medial leaf of the peritoneum and develop the plane deep to the spleen, the splenic vessels, and the tail of the pancreas. Mobilize the splenic flexure of the colon with the lower pole of the spleen. Mobilization of the spleen into the operative field will then be limited by the short gastric vessels and splenocolic ligaments (Fig. 70.3B).

Check the retroperitoneum and bed of the spleen for bleeding. Pack two laparotomy pads into the bed of the spleen.

Anatomic Points

Mobilization of the spleen should not exceed the limits imposed by the gastrosplenic ligament, as it is possible to avulse the short gastric blood vessels running in this ligament. The maneuver described partially recreates the embryonic

midline position of the spleen in the dorsal mesogastrium. Incision of the peritoneum lateral to the spleen allows access to the relatively avascular fusion plane formed by fusion and subsequent degeneration of the original left leaf of dorsal mesogastrium with posterior parietal peritoneum. As the spleen, splenic vessels, and pancreas all begin their development in the dorsal mesogastrium, this fusion plane is posterior to these structures. The splenic flexure of the colon is mobilized with the spleen because of the variable presence of small vessels in this ligament. Placing traction on the short splenocolic ligament can tear the delicate splenic capsule. Although the spleen is to be removed, capsular damage at this point can result in a bloody operative field.

midline position of the spleen in the dorsal mesogastrium. Incision of the peritoneum lateral to the spleen allows access to the relatively avascular fusion plane formed by fusion and subsequent degeneration of the original left leaf of dorsal mesogastrium with posterior parietal peritoneum. As the spleen, splenic vessels, and pancreas all begin their development in the dorsal mesogastrium, this fusion plane is posterior to these structures. The splenic flexure of the colon is mobilized with the spleen because of the variable presence of small vessels in this ligament. Placing traction on the short splenocolic ligament can tear the delicate splenic capsule. Although the spleen is to be removed, capsular damage at this point can result in a bloody operative field.

Division of the Short Gastric Vessels (Fig. 70.4)

Technical Points

Typically, three to four short gastric arteries (with accompanying veins) connect the spleen to the greater curvature of the stomach high up near the cardioesophageal junction. The highest of these is generally the shortest, and the gastric wall closely approximates the upper pole of the spleen. With the spleen mobilized into the operative field, pass a right-angle clamp behind the highest short gastric vessels and doubly ligate and divide them. Be careful not to include the wall of the stomach in the tie. Then, sequentially ligate and divide the remaining short gastric vessels. Inspect the ties on the greater curvature of the stomach. If the gastric wall has been injured or included in a tie, the area should be imbricated with a 3-0 silk Lembert suture.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree