At least 30% of the physical complaints of primary care patients cannot be explained by organic illness (

Kroenke et al., 1994;

Kroenke, 2007). Although understanding the social and psychiatric influences on these complaints is essential for appropriate management, patients with unexplained symptoms present a diagnostic and treatment challenge for even the most empathic and dedicated doctor (

Hartz et al., 2000).

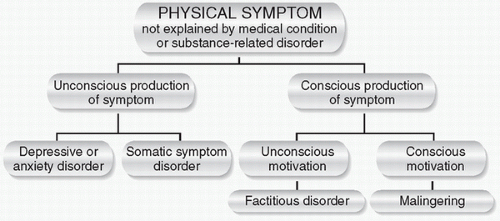

Patients with unexplained physical symptoms fall into two general categories (

Fig. 16-1). In the first category, symptom formation is unconscious. These patients come to the doctor believing that they are medically ill. This category includes patients with

somatic symptom disorders, a group of emotional disorders characterized by physical symptoms that suggest organic pathology (see later text); and patients with depressive illnesses, because “masked depression” (see

Chapter 13) commonly presents with physical symptoms. In the second general category, symptom formation is conscious. Individuals with these conditions, which include

factitious disorders and

malingering, feign mental or physical illness or actually induce physical illness in themselves or in close relatives. In factitious disorders, the symptoms are feigned for unconscious psychological reasons (e.g., to gain attention and care from medical personnel). In malingering, the symptoms are invented for conscious, tangible gain, such as money in a lawsuit or release from legal, work, or school responsibilities.