Snorkel/Chimney and Periscope Visceral Revascularization during Complex Endovascular Aneurysm Repair

Jason T. Lee

Ronald L. Dalman

DEFINITION

Although routine endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) has gained widespread acceptance as the procedure of choice for patients with suitable aortic neck anatomy, the optimal approach to the juxtarenal aortic aneurysm (JAA), often with challenging anatomy at the visceral neck, remains controversial.1 Although open repair is an effective and durable option for patients with JAA, particularly in centers of excellence for low physiologic risk patients,2 endovascular techniques including fenestrated and branched EVAR (FBE) have emerged as effective, potentially less invasive alternatives.3

In the United States, however, lack of widespread availability of FBE has allowed other techniques to emerge, and in this chapter, we describe the increasingly popular “snorkel” or “chimney” technique, defined as a parallel stent graft adjacent to the endograft main body to maintain perfusion to renal and visceral branches during EVAR and placed from a cranial direction, and the “periscope” technique, where the parallel stent graft is placed from the caudal direction.

First described by Greenberg and associates,4 the snorkel strategy can be employed either as a bailout from accidental coverage of vital side branches during deployments requiring close approximation of the main body to the branch artery in question, or the intentional cranial relocation of the EVAR seal zone for JAAs.5, 6, 7, 8

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The challenge for the vascular specialist in treating JAAs revolves around an increasing number of choices for intervention, including traditional suprarenal repair, hybrid type debranching procedures, fenestrated and branched devices in clinical trials or certain centers, and snorkel/chimney/periscope techniques. The choice is most often based on patient physiologic parameters, physician experience with the multitude of techniques, and a very individualized approach to complex aortic anatomy.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Most patients present electively and essentially without symptoms for consideration of repair of their JAA, as it is most often discovered during radiographic workup for vague abdominal discomfort, back pain, or as part of a screening program. A pulsatile, nontender abdominal mass can be elicited on careful abdominal exam. Any signs of persistent abdominal or back pain or hemodynamic instability or compromise should suggest the possibility of an acute aortic pathology and prompt more urgent workup and treatment. Careful attention during the history and physical examination to cardiac and renal comorbidities aids in risk-stratifying the patient for potential repair of their JAA. Because most patients are asymptomatic and aneurysms are repaired to prevent future rupture, some reasonable quality of life must be present for the patient to enjoy the survival advantage.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

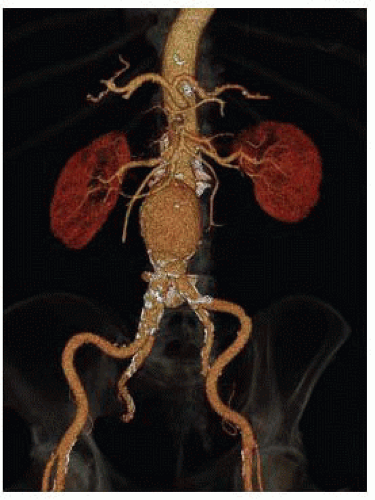

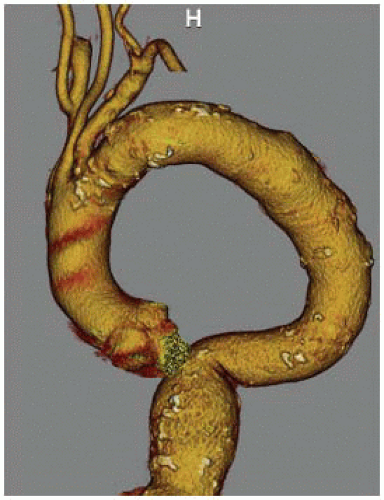

High-quality computed tomography angiography (CT-A) on a modern 64-slice scanner able to produce at least 2-mm-thin cuts is a requirement for treatment with snorkel techniques. These imaging algorithms allow the creation of virtual models of the aneurysm for the surgeon to better appreciate the relationship of branches and potential areas of technical challenge (FIG 1). Patients with compromised kidney function who cannot undertake iodinated contrast are poor candidates for snorkel procedures, as noncontrast scans fail to elucidate thrombus volume, branch artery patency, and luminal diameter in the preoperative planning that is paramount to success.

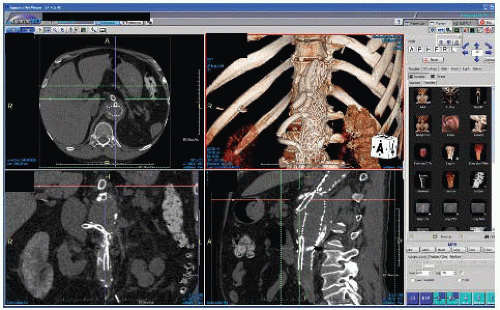

Access to a three-dimensional (3-D) workstation/program and familiarity with reconstruction software by the implanting surgeon for manipulation of the images and creating centerline pathways should be mandatory to most accurately plan device orientation, selection, and sizing (FIG 2).

Because the snorkel technique usually involves access of the brachial artery for delivery of the parallel visceral stent grafts, visualization of the arch and proximal subclavian is

most conveniently obtained by including the chest in the standard CT-A of the abdomen and pelvis. The presence of a challenging type III arch, where the subclavian inserts below the inner curve of the aortic arch, makes the procedure more challenging and many times prohibitive due to concerns about arch manipulation, cerebral emboli, and deliverability of stent grafts (FIG 3). If the patient has already undergone an adequate CT-A abdomen and pelvis and one wishes to avoid the additional contrast load of repeating the study, a noncontrast chest computed tomography (CT) can be performed to visualize the arch but then should be combined with arterial duplex and waveforms of the upper extremities to ensure patency of the axillosubclavian arterial system.

FIG 2 • TeraRecon workstation view highlighting ability to manipulate images in multiple user-defined planes.

For patients with chronic kidney disease, high-grade renal stenosis, atretic kidneys, or multiple visceral and renal vessels involved in the endovascular plan for snorkeling, nuclear medicine split renal function tests can help determine if it is reasonable to sacrifice one of the renal arteries. This can be done in order to simplify the snorkel strategy and keep the number of cranially oriented stent grafts to two, which may have an influence on overall morbidity and mortality from the procedure.1,7,8

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

All patients considered for snorkel/chimney or periscope techniques should have undergone an extensive informed consent discussion related to off-label use of endograft components for treatment of their complex aneurysm. Alternatives often discussed include open surgery with suprarenal clamping, hybrid debranching, referral to a center with access to fenestrated or branched devices, or no surgery at all. Once the decision is made to proceed with the snorkel strategy, we prefer a twosurgeon approach with one performing the femoral access portion and one the brachial access portion. Both surgeons should have reviewed on the 3-D workstation the anatomy, the endovascular plan, and the sequence for deployment.

Access to a hybrid endovascular suite is highly recommended, although not mandatory, for successful completion of these procedures. Fixed imaging provides improved accuracy, reliability, and reproducibility of the anatomy throughout the sequence of the snorkel procedure. Knowledgeable operating room and cath-angio staff should be assigned to these cases and available endografts and wires/catheters as well as backups should all be arranged ahead of time to provide the safest working environment for the patient as well as the operative team.

Choosing the main body endograft, its configuration, and size has been described by numerous authors who all report excellent results overall with a wide variety of devices and formulas.9 In general, we often “oversized” to about 25% to 30% instead of the typical 15% to 20% for standard EVAR to account for the additional fabric infolding to accommodate the snorkel stent(s).

Given the amount of dye often used as well as renal artery manipulation during the most complex of snorkel cases, we prefer to admit the patient the evening before or several hours prior to surgery for additional intravenous hydration when possible.

General anesthesia is preferred, with consideration for preoperative lumbar drainage based on risk of spinal cord ischemia. Arterial monitoring, when necessary, is achieved via the right arm. Adequate venous access can consist of either largebore peripheral intravenous lines (IVs) or a central line. There is usually not a need for autotransfusion or cell saver setups unless an iliac or axillary conduit is planned where there is more potential for early blood loss during the procedure.

Positioning

The hybrid room can be set up as either “head” position (FIG 4) or “right side, table rotated” depending on the type of imaging equipment. With the right arm tucked, the left arm is prepped circumferentially and placed on an armboard at about 75 to 90 degrees while the chest and abdomen down to the groins are prepped. Surgeon A, who will stand at the patient’s right hip, has control of the C-arm and imaging functions and is in charge of obtaining femoral access and delivery of devices from the groins. Surgeon B stands above the outstretched left arm, with an additional sterile table extending off the left hand to allow for wires and catheters to remain sterile and available for arm access during the procedure. The monitor is placed at a slight angle toward the foot of the bed to allow both surgeons to visualize, or a slave monitor can be employed.

TECHNIQUES

SNORKEL/CHIMNEY ENDOVASCULAR ANEURYSM REPAIR

Arm Access

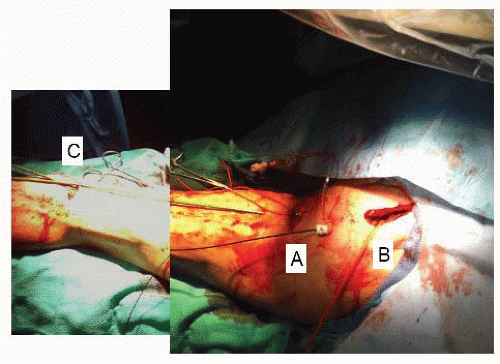

A 5-cm transverse incision slightly below the left axilla over the palpable brachial pulse affords several centimeters of longitudinal exposure of the high brachial artery (FIG 5A). Staying proximal to the deep brachial artery takeoff allows a large enough caliber of brachial artery for typical delivery of two 7-Fr sheaths for a double renal snorkel procedure. At least 7 to 8 cm of healthy brachial artery should be dissected free and slung with vessel loops to allow accurate puncture of the vessel. The two punctures should be placed at least 2 cm apart, and not next to each other, to facilitate later simpler, individual primary closure.

For cases when larger delivery sheaths may need to be inserted or in cases where potentially up to three or four snorkel stents need delivery, then an infraclavicular incision and exposure of the axillary artery for possible 10-mm Dacron conduit placement is recommended (FIG 5B). When this is planned, a 20-Fr or 22-Fr sheath can be inserted to get around the arch and then three 6-Fr or 7-Fr sheaths can be used to cannulate the visceral vessels.

FIG 5 • A. Skin incision via a high brachial incision near the axilla exposes the proximal brachial artery, often giving adequate size for double puncture. B. Infraclavicular incision to expose the axillary artery necessary when three or four snorkel/chimney sheaths needed. A 10-mm or 12-mm Dacron conduit can be sewn into the axillary artery in this position. C. Small incision over palpable brachial artery near antecubital crease can be used when only single snorkel/chimney sheath necessary.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access