Smallpox

Lisa Rotz

Inger Damon

Joanne Cono

NAME OF AGENT

Variola (Smallpox) Virus

MICROBIOLOGY

The etiological agent of smallpox is a double-stranded DNA virus, variola virus, which belongs to the family Poxviridae, genus orthopoxvirus. This genus includes several other related viruses, including vaccinia virus, which is used to produce smallpox vaccine because it induces cross-protective immunity to other orthopoxviruses. These viruses are brick-shaped on electron micrography and measure about 300 by 250 by 200 nm (1).

THEORETICAL AND SCIENTIFIC BACKGROUND

Prior to the eradication of smallpox, humans were the only known natural reservoir. The last known naturally occurring case of smallpox was in Somalia in 1977 (2). Routine vaccination against smallpox was discontinued worldwide in the early 1980s following elimination of the disease through a global eradication program led by the World Health Organization (WHO). Protection against smallpox following vaccination is not lifelong. High-level protection lasts for approximately 5 years, and waning but still substantial protection can persist for up to 10 years following initial vaccination with vaccinia virus, the related orthopoxvirus used in the live-virus vaccine for smallpox (3,4). Protection against death from the disease may persist even longer than protection against disease in vaccinated individuals and may be seen in persons vaccinated over two decades ago (5,6). All children and most adults are now considered susceptible to the development of disease if exposed to variola virus, either because they were never vaccinated or were vaccinated more than 20 years ago and are no longer fully protected. Although the last case of smallpox occurred over 25 years ago, the specter of bioterrorism has raised concerns for the use of this virus as an agent of terrorism (7).

Human-to-human transmission of variola virus usually occurs by inhalation of virus-containing large airborne droplets of saliva from an infected person with subsequent deposition on the oropharyngeal region of the susceptible individual. Transmission usually requires prolonged close contact (face-to-face), although infrequently airborne transmission over greater distances has been described (8). Transmission via direct contact with material from the smallpox pustules or crusted scabs can also occur; however, scabs are much less infectious than respiratory secretions, presumably due to binding of the virions in the fibrin matrix of the scab. During the smallpox era, the overall average secondary attack rate was 58.4% in previously unvaccinated close household contacts and 3.8% in previously vaccinated household contacts (2). Higher attack rates that have been reported from some studies may have been associated with more favorable environmental conditions for transmission (e.g., low heat and low humidity). Because of the lack of natural and vaccine-induced immunity, it is difficult to predict the exact attack rates in today’s population.

Following deposition on the mucous membranes, the virus passes into local lymph nodes with a brief period of viremia. Next, a latent period of up to 2 weeks occurs during which the virus multiplies in the reticuloendothelial system. The onset of initial symptoms (the prodromal phase) is preceded by another short viremic period. During the prodromal phase, the virus multiplies and invades the mucous membranes of the mouth and dermal layers of the skin. This leads to the development of the oropharyngeal and skin lesions that contain infectious viral particles (2). Transmission of the virus via large airborne droplets remains highest during the first 7 to 10 days following the onset of rash but decreases significantly during the later stages of the disease (9).

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Notify public health officials immediately of any suspected smallpox patient. The three clinical forms of smallpox, ordinary, flat, or hemorrhagic, may occur in unvaccinated or distantly vaccinated individuals. During the smallpox era, ordinary smallpox generally accounted for about 90% of the cases. Flat and hemorrhagic clinical presentations accounted for a much lower percentage (7% and <3%, respectively) (1,10,11). An additional form, modified type, was seen in individuals with previous vaccination who were no longer fully protected. Although the case-fatality rate varied with the different clinical forms of smallpox, it was approximately 30% in unvaccinated individuals.

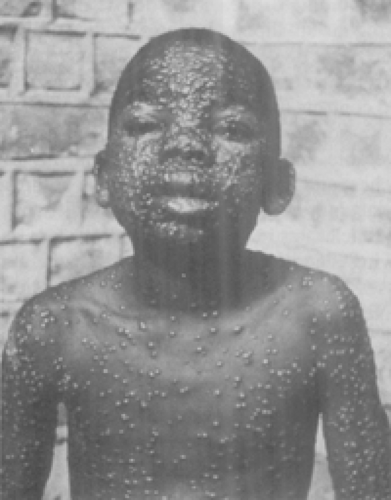

Differing clinical forms of disease are thought to be caused by the host’s response to infection rather than different strains of virus. The clinical course of ordinary or typical smallpox begins with an asymptomatic incubation period following infection, which may last from 7 to 17 days (average 12 to 14 days). After the incubation period, the first symptoms begin with a prodromal phase and include fever, malaise, prostration, headache, and backache. During the prodromal phase, individuals often feel very ill, which may prompt them to remain at home or seek medical care. This nonspecific viral syndrome phase usually lasts from 2 to 4 days before the onset of the rash or exanthem phase. Virus transmissibility or infectiousness begins as the fever peaks at the end of the prodrome period and coincides with the onset of the rash. This rash begins as lesions on the buccal and pharyngeal mucosa, soon followed by the appearance of rash on the face, forearms, and hands (2,9). The rash spreads downward, and within a day or so, the trunk and lower limbs are involved, including the palms and soles. Usually the rash is evident on most parts of the body within 24 hours. Ultimately the distribution of the rash is centrifugal: most profuse on the face, and more abundant on the forearms than the upper arms, and on the lower legs than the thighs (Fig. 8-1).

Figure 8-1. This photograph depicts an African child displaying the typical centrifugal rash distribution of smallpox on his face, chest, and arms. (From CDC, Public Health Images Library # 3268.) |

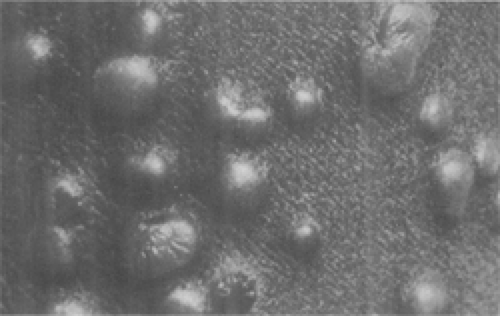

Figure 8-2. Closeup of smallpox pustules found on the thigh of a patient during day 6 of the rash. (From CDC/Dr. Paul B. Dean, Public Health Images Library # 2553.) |

The lesions of the rash begin as macules, which are small discolored skin patches. The macules progress to firm papules, then vesicles, which soon become opaque and pustular (Figure 8.2) Progression of the rash is slower than varicella (chickenpox) with usually 1 to 2 days between each stage (macule to papule to pustule). In addition, the lesions tend to progress through stages together so lesions in any area of the body are all in the same stage of development. The pustules, which are considered the characteristic lesions of smallpox, are typically raised and firm to the touch, or “shotty,” as if BB pellets were embedded in the skin. Approximately 8 to 9 days after onset of the rash, the pustules become pitlike and dimpled. Around day 14, the pustules dry up and become crusted. By about day 19, after onset of prodromal symptoms, most pustules begin to scab and separate, with those on the palms and soles separating last. Virus particles can be present in large numbers in the scabs but are generally not highly infectious because they are enclosed within the hard, dry scab.

Flat-type or malignant smallpox, a very rare manifestation of the disease, is believed to be associated with a deficient cellular immune response to variola virus (2). This form of the disease is characterized by a rapidly progressive septic state and is very rare in previously vaccinated individuals. The skin lesions develop slowly, become confluent, and remain flat and soft, never fully progressing to the pustular stage. They have been described as “velvety” to the touch, and sections of the skin where lesions have become confluent may slough off. The majority of flat-type smallpox cases are fatal (97% among unvaccinated individuals), but if the patient survives, the lesions gradually disappear without forming scabs.

Hemorrhagic-type smallpox, which is also rare, is associated with petechiae (minute hemorrhagic spots) in the skin and bleeding from the conjunctiva and mucous membranes. This type of smallpox maintains a higher level of prolonged viremia as opposed to the other clinical forms of the disease. Illness with severe prodromal symptoms that include high fever, severe headache, and abdominal pain begins after a sometimes shortened incubation period. Soon after illness onset, a dusky erythema develops, which is followed by petechiae and skin and mucosal hemorrhages. Death usually occurs within the first week of illness (1), often before lesions more characteristic of smallpox rash develop. The two forms of hemorrhagic-type smallpox, early and late, are differentiated by the occurrence of hemorrhages after the appearance of the rash in the late form. Hemorrhagic-type smallpox occurs

among all ages and in both sexes but is more common in adults and almost universally fatal. Pregnant women also seem to be more susceptible to developing this form of smallpox than other adults. The underlying molecular biologic reasons for the severe toxemia and other effects of this form of smallpox are unclear.

among all ages and in both sexes but is more common in adults and almost universally fatal. Pregnant women also seem to be more susceptible to developing this form of smallpox than other adults. The underlying molecular biologic reasons for the severe toxemia and other effects of this form of smallpox are unclear.

A modified form of smallpox can occur in previously vaccinated individuals. The modification referred to in this form of smallpox relates to the character and development of the rash with more rapid progression and resolution of the lesions. In general, the prodrome stage with fever still occurs and may also consist of severe headache and backache, with a duration that may not be shortened. However, once the skin lesions appear, they generally evolve more quickly with crusting completed within 10 days. The lesions may be fewer in number and are more superficial than those seen in ordinary-type smallpox. Although a febrile prodrome generally still occurs, fever during the rash stage is usually absent with this modified form of smallpox.

In situations where smallpox was not expected, smallpox was at times confused with chickenpox. In contrast to chickenpox, all lesions on any one part of the body are at the same stage of development with smallpox. Distribution of the rash in chickenpox is uniform or centripetal; there may be more lesions on the trunk than on the face and distal limbs, and abdominal involvement is equivalent to back involvement. The rash of chickenpox manifests as uniloculated vesicles that do not umbilicate or dimple. The vesicles may also have irregular borders. There are usually no lesions on the palms and soles in chickenpox.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has developed several resources that can be used to assist clinicians in evaluating acute generalized vesicular or pustular rash illnesses for their likelihood of being smallpox in a nonoutbreak setting. These tools can be found on the CDC web site at http://www.bt.cdc.gov/agent/smallpox/diagnosis/evalposter.asp and include an interactive online version of the clinical evaluation algorithm.

A number of nucleic acid polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays detect the presence of orthopoxvirus in clinical specimens. The speciation of orthopoxvirus is then facilitated by endonuclease restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis (12,13,14). The Laboratory Response Network (LRN), an affiliation of public health laboratories with the Association of Public Health Laboratories (APHL) and CDC, has a variety of real-time PCR assays that can be used for the detection of orthopoxviruses in clinical specimens. A subset of LRN laboratories with appropriate biocontainment capabalities, also has specific smallpox (variola) testing capacity. Electron microscopy, in facilities with well-trained personnel, is another sensitive method for evaluating rash specimens for the presence of poxvirus particles.

MEDICAL MANAGEMENT

There are no proven curative treatments for clinical smallpox. Medical management of a patient with smallpox is mainly supportive and consists of (a) isolation of the patient to prevent transmission of the smallpox (variola) virus to nonimmune persons, (b) monitoring and maintaining fluid and electrolyte balance, (c) skin care, and (d) monitoring for and treatment of complications. Recovery from smallpox results in prolonged immunity to reinfection with variola virus. Variola virus does not persist in the body after recovery.

Hospitalized suspected and confirmed smallpox patients should be isolated in a negative-pressure room, and strict airborne and contact precautions should be maintained at all times. These precautions include use of N-95 or greater respirators, gloves and gowns, and careful hand washing for all health care workers entering the patient’s room. If possible, previously vaccinated personnel should be utilized to evaluate and care for suspected or confirmed cases of smallpox. If previously vaccinated personnel are unavailable, staff without contraindications to vaccination can provide care utilizing the appropriate airborne and contact personal protective equipment, with vaccination provided as soon as possible (15).

During the vesicular and pustular stages of smallpox, patients may experience significant fluid losses and become hypovolemic or develop shock. Fluid loss can result from (a) fever, (b) nausea and vomiting, (c) decreased fluid intake due to swallowing discomfort from pharyngeal lesions, (d) body fluid shifts from the vascular bed into the subcutaneous tissue, and (e) massive skin desquamation in patients with extensive confluent lesions. Electrolyte and protein loss may also occur in these patients. Fluid and electrolyte balance should be monitored in hospitalized patients with appropriate oral or intravenous correction of imbalances. Patients with less severe disease should be encouraged to maintain good oral intake of fluids.

Nausea and vomiting can occur in the earlier stages of smallpox, especially in the prodromal period before rash development, and should be treated symptomatically. Occasionally, diarrhea may occur in the prodromal period or in the second week of illness and should also be treated symptomatically. Acute dilation of the stomach rarely occurs and is more common in infants. In some severe cases of smallpox (especially flat-type), extensive viral infection of the intestinal mucosa occurs with sloughing of the mucosal membrane. Most of these cases are fatal.

Occasionally, bacterial superinfections may also occur and should be treated with appropriate antibiotic therapy. Bacterial superinfections can include abscesses of skin lesions, pneumonia, osteomyelitis, joint infections, and septicemia. Laboratory diagnostics (e.g., Gram stain, culture, and antibiotic susceptibility testing) should be performed to help guide antibiotic therapy.

Viral bronchitis and pneumonitis can be complications of severe smallpox. Treatment is symptomatic with measures to treat hypoxemia with supplemental oxygen and/or intubation/ventilation as indicated. Secondary bacterial pneumonia can occur and should be treated with appropriate antibiotics as guided by laboratory diagnostics (e.g., Gram stain, culture, and antibiotic susceptibility testing). Pulmonary edema is common in the more severe forms of smallpox (hemorrhagic and flat-type) and should be treated with careful monitoring of oxygenation, fluid status, blood pressure with supplemental oxygen, and diuretics administered as needed. Although cough is not usually a prominent symptom of clinical smallpox, patients with a cough during the first week of illness may transmit disease more readily than those without a cough because this is the period when oral secretions contain the largest amount of virus. A cough is more likely to produce small particle aerosols that can travel over greater distances. Patients

that develop a cough later in the course of disease (after day 10), when viral counts in secretions are lower, are not as infectious as those that develop coughs earlier.

that develop a cough later in the course of disease (after day 10), when viral counts in secretions are lower, are not as infectious as those that develop coughs earlier.

Corneal ulceration and/or keratitis, complications sometimes leading to blindness, occurred more frequently in hemorrhagic-type smallpox but were occasionally seen in the more typical ordinary-type smallpox. Occasionally, blindness can occur, but it generally is a result of an underlying condition such as malnutrition and/or an opportunistic ocular bacterial infection. The virus itself does not cause the corneal opacity that can lead to blindness. In one case series (10), corneal ulcers occurred in 1% of nonhemorrhagic-type smallpox cases, and keratitis occurred in about 0.25%. Corneal ulcerations can appear around the second week of illness and begin at the corneal margins. Ulcers can heal rapidly, leaving a minor opacity or, on occasion, may cause severe corneal scarring.

Encephalitis occurs in about 1 out of every 500 cases of smallpox. It usually appears between day 6 and day 10 of illness when the rash is still in the papular or vesicular stage. During the smallpox era, this complication was a minor contributor to the case-fatality rate of typical smallpox, the most common form of smallpox. Although sometimes slow, recovery was usually complete.

Multiple studies of antivirals during the smallpox eradication failed to show significant benefit in the treatment of smallpox (16,17). Cidofovir (Vistide, Gilead Sciences, Foster City, CA) has shown some in vitro and in vivo (animal studies) activity against orthopoxviruses (18,19,20). However, its true effectiveness for treating clinical smallpox or vaccine adverse events is not known (9). This medication is currently labeled for the treatment of cytomegalovirus (CMV) retinitis and has been associated with renal failure. Vaccinia human immunoglobulin (VIG), which is licensed to treat certain post–smallpox vaccination adverse effects, has shown no efficacy in the treatment of clinically established smallpox (15,21).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree