Serrated/Hyperplastic Polyps

Introduction. Serrated polyps are benign, epithelial polyps characterized by serrated architecture and generally bland (nondysplastic) cytology. Our understanding of these polyps has evolved considerably, evolution has inevitably led to a major change in their classification, nomenclature, and clinical management. Although there were reports associating hyperplastic polyps with adenocarcinoma, until about 2003, all such polyps were called hyperplastic polyps (HPs), and considered benign with very little preneoplastic potential. In a very elegant study, Torlakovic et al.

127 showed that HPs consisted of a heterogeneous group of lesions, which could be separated into many distinct morphologic subtypes, and some of them could be preneoplastic. Since then, many studies have shown that indeed this is a heterogeneous group of lesions that have differences in their molecular phenotype, morphology, distribution in the large bowel, and preneoplastic potential, and our entire outlook on HPs has changed. It has become clear that these polyps may progress to colon cancer through separate pathways, one of which is now referred to as the “serrated pathway” and often involves microsatellite instability (MSI). The nomenclature of these polyps has evolved and remains a source of controversy. However, the most recent WHO has proposed a revised classification of these lesions with a “consensus” nomenclature.

128 The common unifying feature of most of these polyps appears to be a serrated architecture, and “serrated polyps” may be the best umbrella term describing this family of lesions and the various subtypes referred to by their specific names. These polyps occur predominantly in the large bowel and a variant of them in the appendix, rarely in the small bowel, but these are all are unrelated to and morphologically different from hyperplastic polyps in the stomach.

Nomenclature and classification. The nomenclature and classification of serrated polyps continue to evolve, especially as difficulties in classification become apparent. These entities have suffered from poor choice of names almost since their beginning. The term “hyperplastic” polyp that has been in use for decades is a misnomer as the proliferative index of cells in the lesion is lower compared to normal colonic epithelium.

129 Similarly, the original term “metaplastic” polyp that predated HP is also considered inappropriate, although logical at the time as the common variants have numerous mucus-producing cells resembling gastric mucosa, and at least one subset does seem to have a gastric phenotype.

130 The current nomenclature and subtyping of the various types of serrated polyp have largely been derived from the study by Torlakovic et al.,

127 which used computer-generated grouping based on a number of morphologic characteristics. The term HP is retained both for historic reasons as well as because it helps to differentiate these from the other and more ominous group of sessile serrated polyps (SSPs). It is unclear if the separation of HPs into microvesicular, goblet cell-rich, and mucin-poor subtypes has any clinical relevance, although evidence is accumulating that some of these may have distinct molecular phenotype, possibly different natural history, and preneoplastic potential. However, in clinical practice, so far subclassification of the HPs into these subtypes is not mandated.

The major controversy that surrounds the nomenclature of the serrated polyps is with regard to their neoplastic potential. The original description of dysplastic serrated polyps, which were considered as the only preneoplastic serrated polyp, classified them all as serrated adenomas, although subsequently these have been found to consist of several variants as discussed later.

From a nomenclature viewpoint, SSPs pose the greatest problem. Initially these were called “HP with

abnormal proliferation” or “variant HP.” Both terms were discarded as neither of these show increased proliferation nor are the terms sufficiently different from HPs to justify special attention.

127 SSP was considered an appropriate option, although conventional HPs are also sessile and serrated, while some SSPs are distinctly polypoid.

Some feel that this term SSP also does not connote the preneoplastic potential of these polyps and may not get the proper attention from the clinicians, hence the alternate designation of serrated sessile adenoma (SSA). Serrated adenomas with dysplasia as initially described by Longacre and Fenoglio-Preiser

131 are now called “traditional” serrated adenoma (TSA), although this entity has also evolved considerably from its initial descriptions. As the latter is now recognized as a distinct entity, it leaves the issue of what to call SSP when they become dysplastic. Options are to call them SSP or SSA with and without dysplasia, which for those using the term SSA potentially leaves us with adenomas with and without dysplasia, which is ridiculously confusing and something of an oxymoron. Another issue with the term SSA is the potential to be confused with TSA, and clinicians may also confuse these to represent lesions in the conventional adenomatous pathway.

A consensus between experts could not be reached as to which terms to use; hence, both the WHO and AJCC suggest use of either SSP or SSA (SSP/A) to be acceptable for nondysplastic lesions.

128 Since then, depending on their personal preferences, pathologists and researchers have been using either SSP or SSA, or some use the hybrid term SSP/A. It would have been much easier to use SSP for the nondysplastic variant and SSA for the dysplastic variant. The European organizations and pathologists have stayed away from both terms and call these “serrated lesions.”

132 In practice, we prefer to use the terms “SSP” for the nondysplastic polyps, and when dysplasia is present, we qualify this as “SSP with dysplasia” as per the WHO, realizing that one also needs to classify the dysplasia (serrated or conventional type) and grade it. Even this is a problem for those that prefer the term “no evidence of high grade dysplasia” rather than “low grade dysplasia”, for the diagnosis “SSP/A with no evidence of high grade dysplasia” could mean either no dysplasia or low grade dysplasia.

Most unclassifiable polyps are mixed polyps, and one may need to spell out the different elements present, especially as these may range from HP through SSP, with or without low grade and/or high grade dysplasia, and invasive carcinoma, which may be of the serrated type, microsatellite unstable, but sometimes microsatellite stable. The dysplasia can be of conventional type or serrated type (see subsequent discussion). Currently we divide serrated polyps into various categories as shown in

Table 20-3, which is a slight modification of the WHO classification. To cover all such polyps that cannot be included under the current WHO classification, we have added an unclassified category (

Table 20-3).

The terminology of serrated polyps is confusing even for pathologists who should be familiar with the evolving pathologic classifications, so one can understand the challenge it poses to practicing gastroenterologists. This was shown in a study looking at the interpretation of various issues related to the serrated polyps when clinicians from diverse types of practices were questioned.

133 Some of the confusion should subside as the American Gastroenterology Association (AGA) has now published the surveillance guidelines for these polyps (discussed later), albeit on precious few data.

Hyperplastic polyps. These represent the most common variety of the serrated polyps in practice constituting at least 75% of all serrated polyps; however, their prevalence varies markedly in different parts of the world and correlates with the prevalence of CRC in given populations. Thus, in Europe and North America, they are very frequent, occurring in up to 85% of adults, while in low-incidence countries they are found in only 2% to 3%.

134 Although minor gender differences have been reported, there does not appear to be a strong gender predilection. HPs were thought to be the most common large bowel polyp. Original studies of the frequency of HPs were carried out on polyps excised or biopsied proctoscopically, and therefore applied only to polyps occurring in the rectosigmoid, where they are abundant (at least in North America).

135 However, the majority of proximal polyps encountered in clinical practice, and particularly on colonoscopy, prove to be adenomas.

136,

137,

138 Similarly, in many autopsy series, adenomas outnumber HPs.

139,

140,

141 Most HPs occur in the rectosigmoid although a scattering can be found in all parts of the large bowel. This contrasts to SSP, which tend to have a much more uniform distribution around the colon. This results in distal polyps being mostly HP, but more proximal polyps being much more likely to be SSPs. It also needs to be realized that most of the epidemiologic data were prior to recognition of SSP and need to be revisited in the era of completely revised classification of serrated polyps. In a study of 1,479 patients using a current classification scheme, adenomas were the most common of the polyps (65%), followed by HP (30%), SSP (3.9%), TSA (0.7%), and mixed HP and adenoma (0.7%).

138

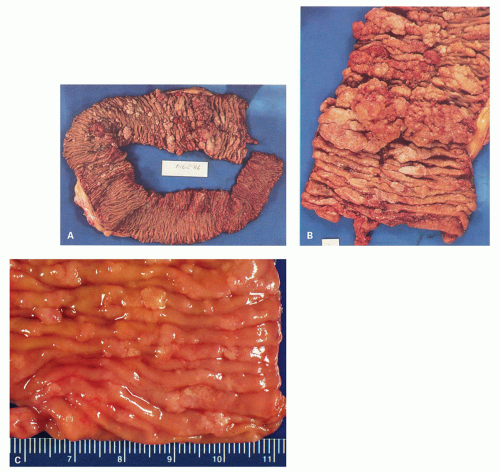

Clinical Features These are generally small, virtually never cause symptoms unless they grow large, or are associated with other lesions. These are often found incidentally at colonoscopy, in surgical specimens, at autopsy, and on air-contrast barium studies.

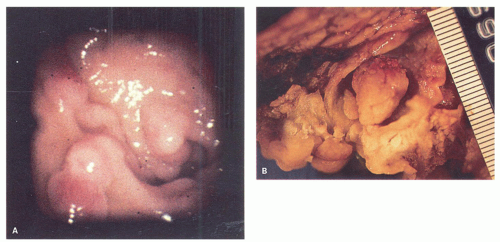

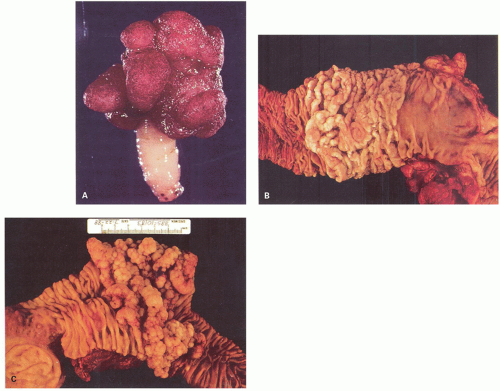

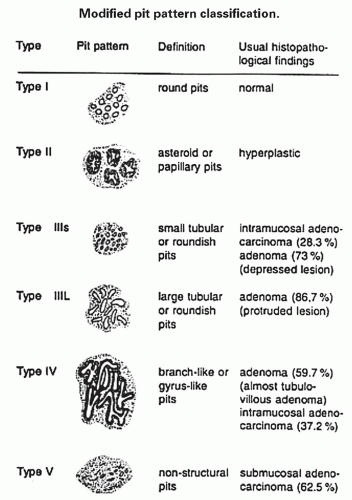

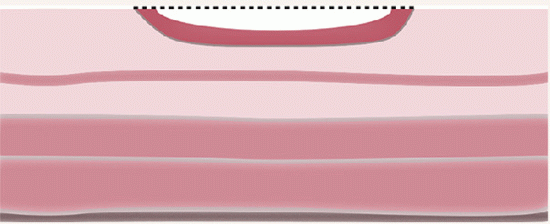

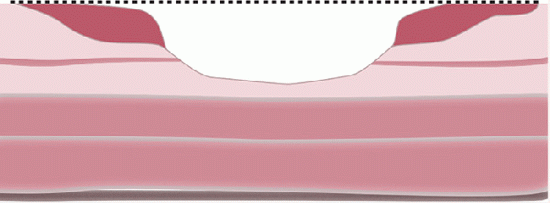

Gross and Endoscopic Appearances Most HPs are <5 mm in diameter, sessile, and similar in color to the background mucosa (

Fig. 20-17). A small proportion is between 0.5 and 1 cm. Polyps >1 cm in diameter are rare and tend to be often pedunculated, and as they get larger, care must be taken to differentiate them from SSP. They appear like pearl-colored dew drops raised from the surface and tend to flatten under pressure or become harder to see when the lumen is fully distended during colonoscopy. Macroscopically and therefore endoscopically, it may be difficult to differentiate small adenomas from HPs; however, with improving techniques (high-resolution endoscopy, narrow band imaging [NBI] or chromoendoscopy), differentiating features have been recognized, especially in the patterns of the luminal openings of the crypts (pit patterns)

142,

143,

144,

145,

146 (

Figs. 20-17B,C and

20-18). The openings of the HPs seem to be larger compared to adjacent normal crypts. The shapes vary from oval in the goblet cell-rich HP to serrated/stellate in microvesicular HPs. The current standard of practice is to remove these completely and submit them for histology for proper classification; hence, reliable differentiation during colonoscopy is not that critical.

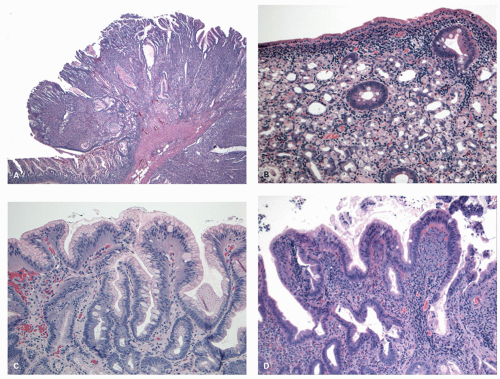

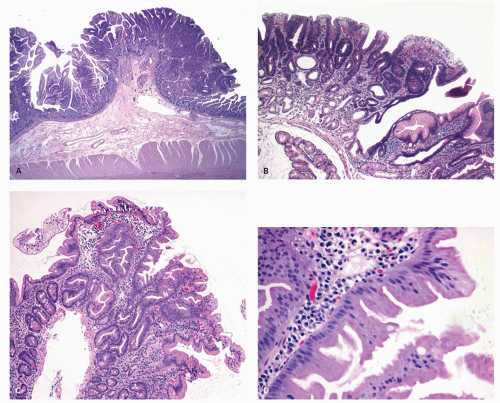

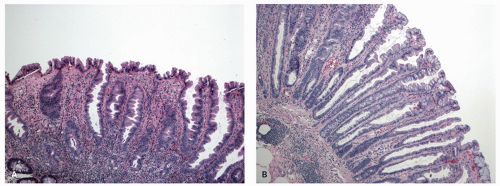

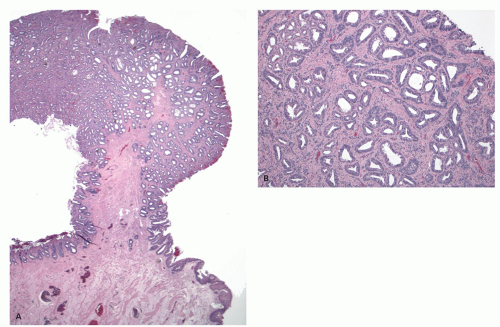

Histology Three morphologic variants of HP are recognized— microvesicular (the most common), goblet cell (the most frequently missed), and mucin-poor (the least understood) types.

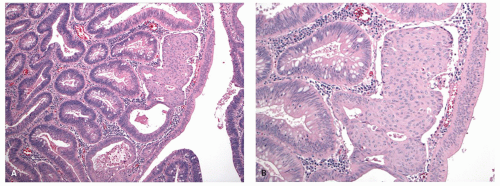

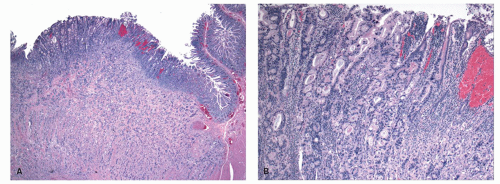

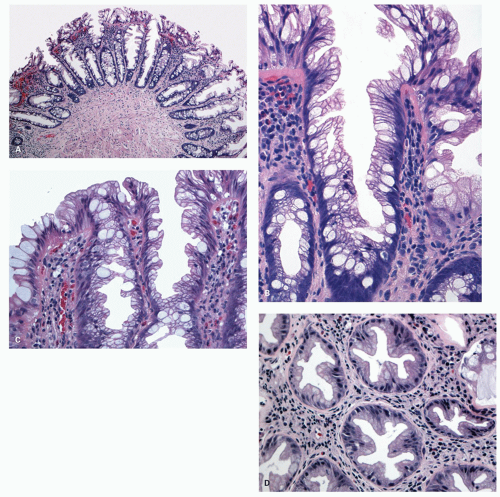

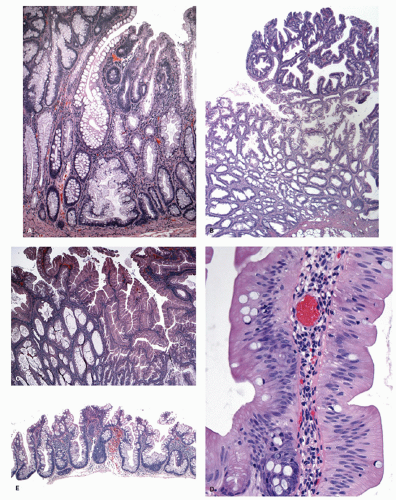

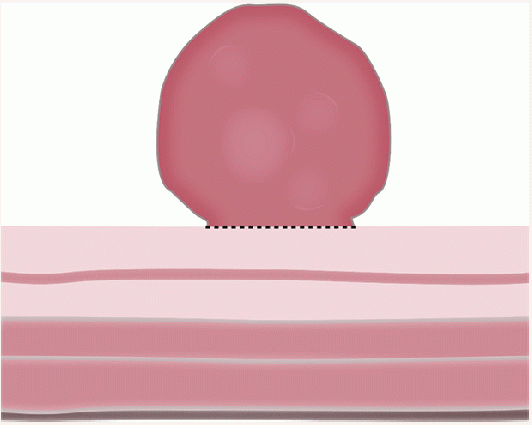

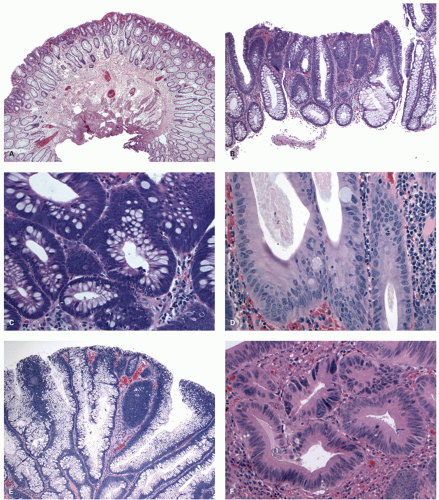

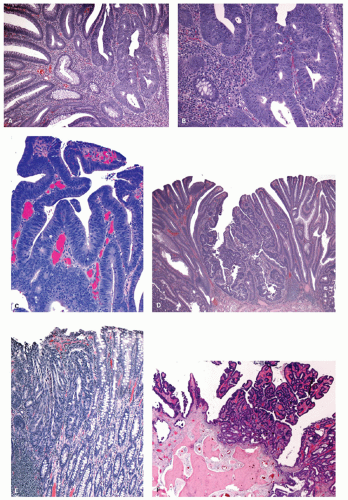

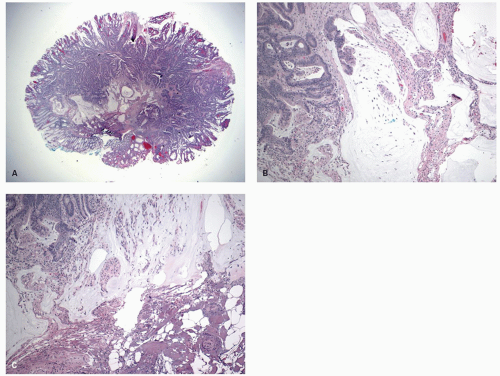

MICROVESICULAR HYPERPLASTIC POLYP (MVHP). This is the classic prototype HP

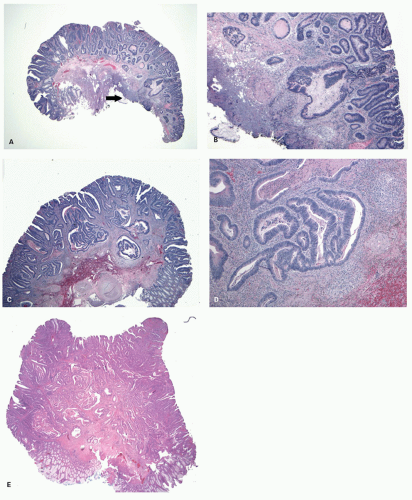

127 and is composed of straight crypts that are often narrow at the bases (carrot shaped). The serrations develop as one approaches the surface, being most prominent in the top half of the crypts (

Fig. 20-19A-C). The bases are lined by more immature/smaller appearing cells that also contain endocrine cells and rarely Paneth cells. The cells have fine droplets of mucin, with or without interspersed goblet cells. The crypts appear stellate on cross section, as often seen in tangentially oriented biopsies (

Fig. 20-19C,D). Nuclear enlargement and mitosis are limited to the bottom one-third of the crypts. In contrast to most adenomas, the nuclei of HPs are smallest in the superficial part of the crypt; they also lack the stratification and nuclear hyperchromatism, so characteristic of adenomas. The nuclear chromatin is more open than those usually seen in adenomas, and nucleoli are inconspicuous or small, and only seen near the crypt bases. The cells in the crypt bases can be easily confused with those of adenomas in some cases; however, one needs to look for evidence of maturation toward the surface. Occasionally bizarre nuclei simulating virally infected cells may be seen that are of no clinical significance (

Fig. 20-20E,F). Branching crypts can be seen in typical MVHP and on its own should not lead to diagnosis of SSP. A prominent subepithelial collagen band similar to that seen in collagenous colitis is sometimes present but is confined entirely to the polyp. The lamina propria may be normal appearing, or sometimes show hemosiderin-laden macrophages, indicative of previous hemorrhage. The muscularis mucosae is usually thickened, and its fibers are splayed; some may venture up between the crypt bases similar to prolapsing mucosa (

Fig. 20-19A). This finding can be prominent in the larger polyps, especially those that are closer to the anal verge, sometimes causing diagnostic difficulties with mucosal prolapse. Inverted growth into or beneath the muscularis mucosae can occur (

Fig. 20-20), especially in most distally located polyps.

GOBLET CELL HYPERPLASTIC POLYPS (GCHP). These are much less common than MVHP, predominantly seen in the left side of the colon, smaller, and least serrated of all the serrated polyps,

127 and so can easily be overlooked in biopsies of polyps (

Fig. 20-21A,B). They are slightly raised above the surface; the crypts tend to be longer and wider and have a more dilated lumen, which is most apparent when adjacent normal crypts are available for comparison. The lining cells are predominantly goblet and absorptive cells, hence the name. The serrations are seen toward the surface, but are much less prominent compared to other serrated polyps, and sometimes almost, and sometimes completely, absent. The nuclear features and composition of the cells at the crypt bases are similar to that of MVHP.

MUCIN-POOR HYPERPLASTIC POLYPS (MDHP). These are least common of the HPs, and the least studied member of this group (

Fig. 20-22A,B). They seem to resemble mostly MVHP; however, they are lined by cells that lack mucin.

127 They often have reactive-type nuclear atypia and lamina propria inflammation. It is unclear if this a separate entity or merely an inflamed MVHP with reactive changes.

DYSPLASIA IN HYPERPLASTIC POLYPS. This is vanishingly rare, but potential examples in which there appears to

be no other explanation are shown in a GCHP in

Fig. 20-21C,D and in a MVHP in

Fig. 20-21E.

Sessile serrated polyps (synonym sessile serrated adenoma) (SSP, SSA, SSP/A). These have been reported to constitute about 10% to 40% of all serrated polyps. The variation in the incidence and prevalence of these polyps in different parts of the world still remains unclear as studies are lacking, although some studies suggest that differences are likely minor.

147 The large variations in the reporting of these polyps seen even in various parts of United States are likely due to marked interobserver variability. The true prevalence in our experience appears to be about 15% to 20% of all serrated polyps. In one prospective study these were found to constitute about 9% of all colonic polyps.

148

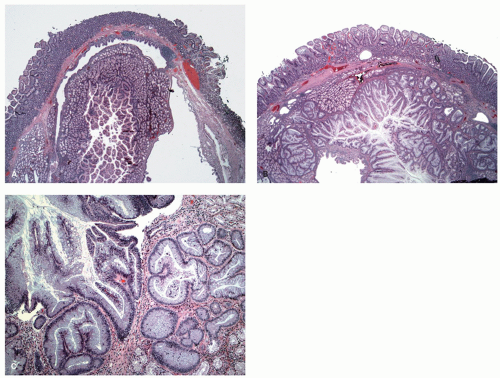

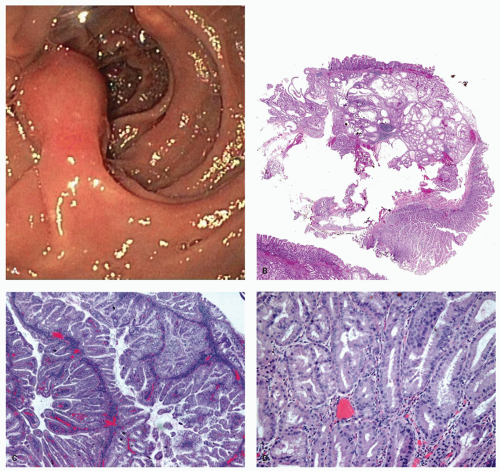

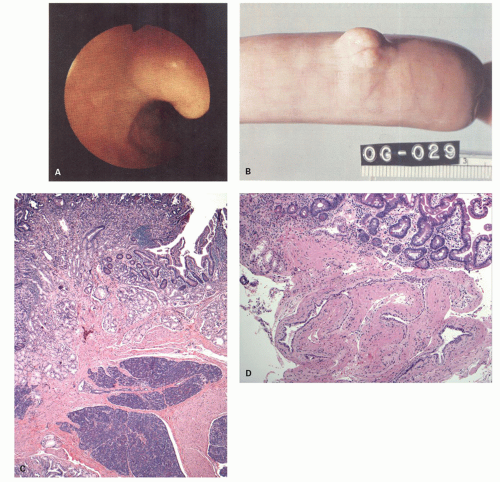

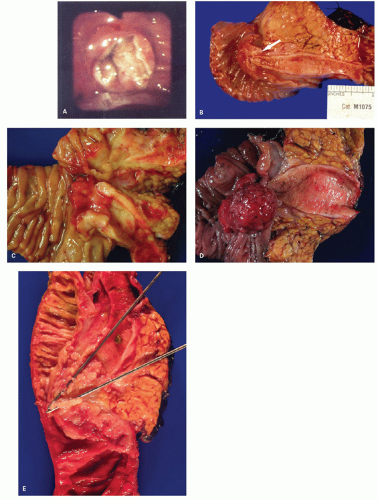

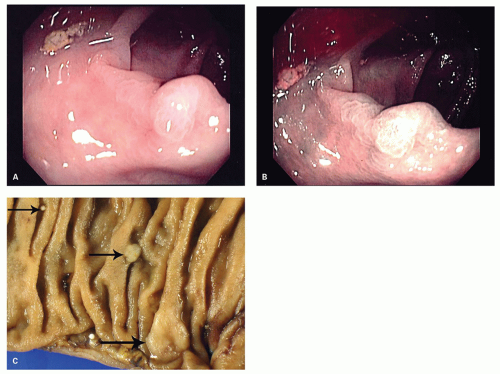

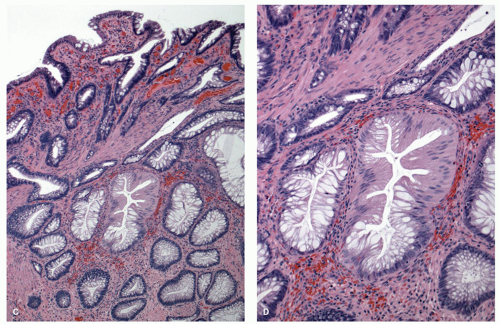

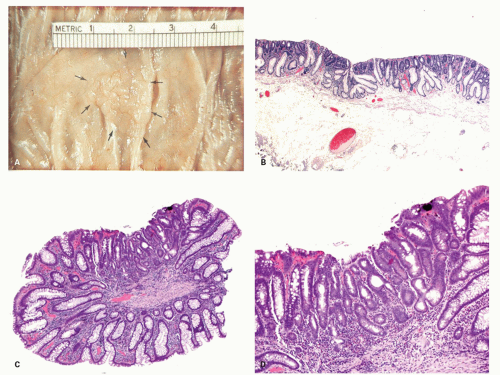

Clinical Features Clinically these are asymptomatic similar to other HPs.

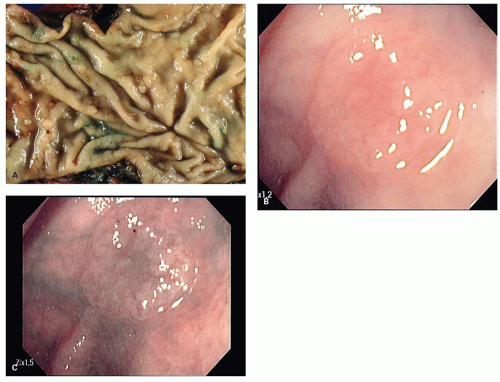

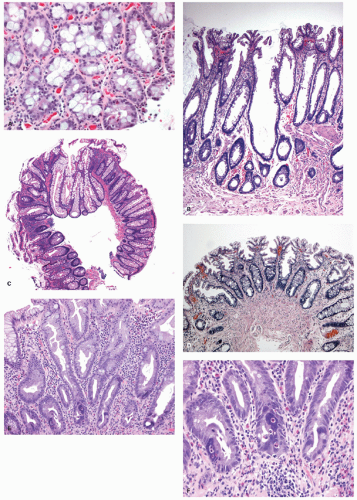

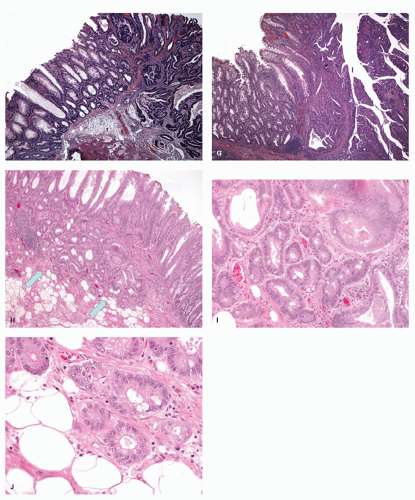

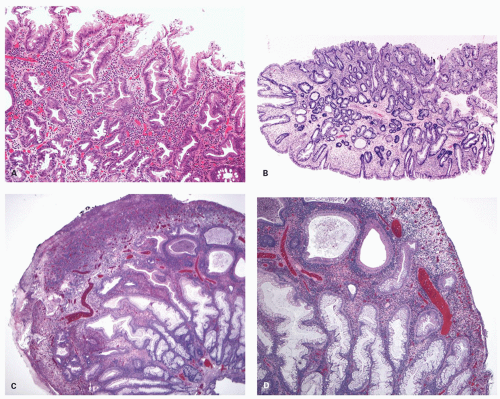

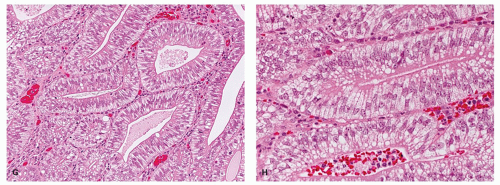

Gross and Endoscopic Findings These polyps are found throughout the large bowel, but relative to all serrated polyps tend to be more common on the right side. The mean size of SSP is larger than HP, and about >50% are larger than 0.5 cm and about 15% to 20% are larger than 1 cm. They are mostly sessile,

slightly raised over the surface with a smooth surface, and often covered with yellow mucus. While the pit patterns of SSP appear similar to MVHP and could be difficult to differentiate from it, subtle differences between these have noted on NBI endoscopy

149 (

Fig. 20-23A,B).

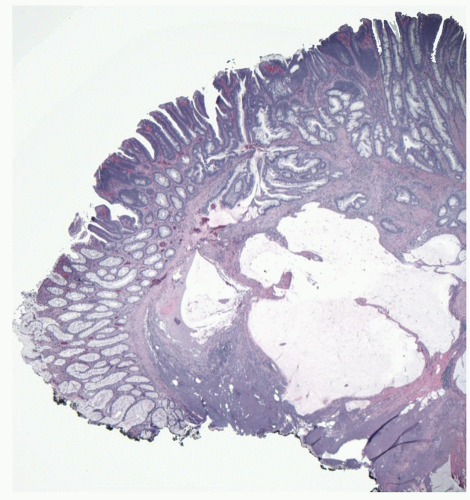

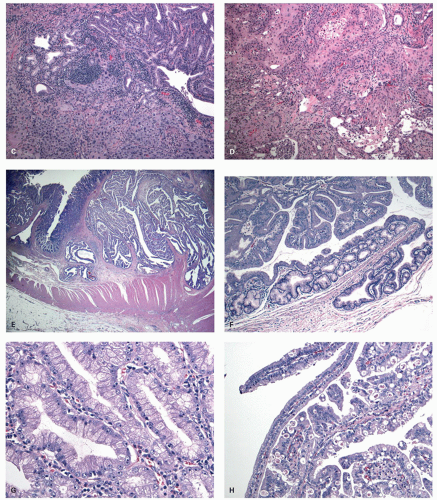

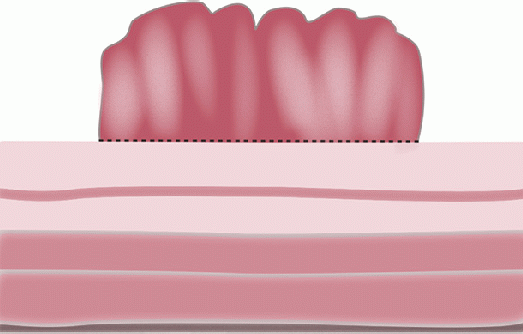

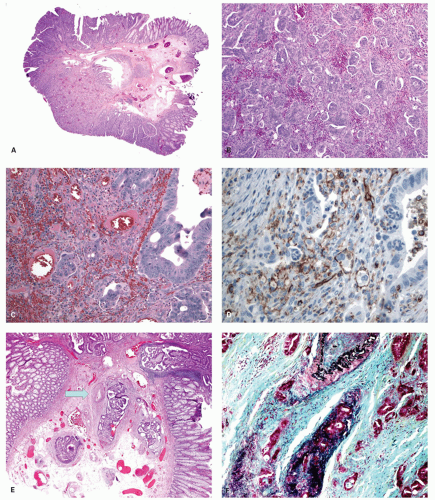

Histology These lesions initially may look like HPs with many features that appear similar, but on closer look, many differences are usually apparent; however, the discriminating features can be focal or sometimes only evident on serial sectioning or deeper levels. The difference is that the architecture is disturbed, while the proliferative zone of the crypts appears abnormal and asymmetric as shown by Ki-67 staining (see later). This leads to abnormal shape and architecture of the crypts (usually the feature most easily recognized at scanning power), with abnormal maturation of cells at the crypt bases (

Figs. 20-24 and

20-25). The shape of the crypts tend to be flask shaped with basal dilatation, or inverted “T” or “L” shaped, branched and sometimes referred to as boot shaped (

Fig. 20-24). Crypt branching and inverted growth beneath the muscularis mucosae are other architectural features that can be seen even at low power, but are features that can also seen with other types of serrated polyps (

Fig. 20-25). The serrations of luminal epithelium tend to be more marked, almost hyper-serrated, at the surface, but is sometimes just as marked, and occasionally more marked, in the crypt bases. The nuclei at the crypt bases can be larger and vesicular with sometimes small nucleoli. These nuclear changes may extend up to the top two-thirds of the crypts, although the surface still appears to mature. Dystrophic goblet cells with their nuclei toward the crypt lumen rather than sitting on the basement membrane may be present (

Fig. 20-25A). Conventional adenoma-like dysplastic features are absent. The cellular composition of SSP is similar to MVHP, and in fact in many SSP, except for a few typical crypts, the rest of the lesion may be indistinguishable from MVHP (

Fig. 20-25C,D). Because of many similarities between these two, it has been proposed that these may be related and represent stages of the same

lesion.

147 Molecular data also support this hypothesis (see later). However, rarely one can see genuine SSPs consisting of only one or two crypts (

Fig. 20-25E), suggesting that at least some of these polyps have this pattern ab initio. The issue is why some apparently typical HPs continue to grow as such while others develop features of SSP?

Serrated polyps with dysplasia. Use of the term “serrated adenoma,” not further qualified, has ceased to exist. For such a simple potentially useful term this seems a total waste, especially given the terminological chaos that applies to these polyps. Dysplasia and carcinoma in serrated polyps were first described in 1984 by Urbanski et al.

150 It is now apparent that dysplasia in serrated polyps tend to occur in two major situations:

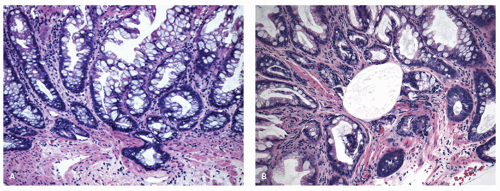

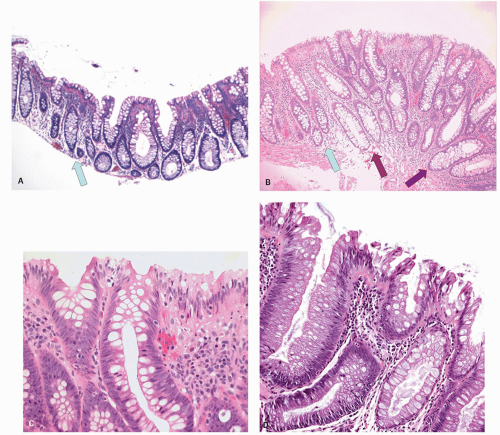

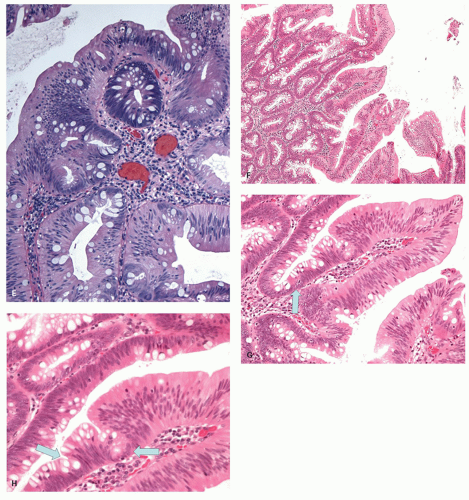

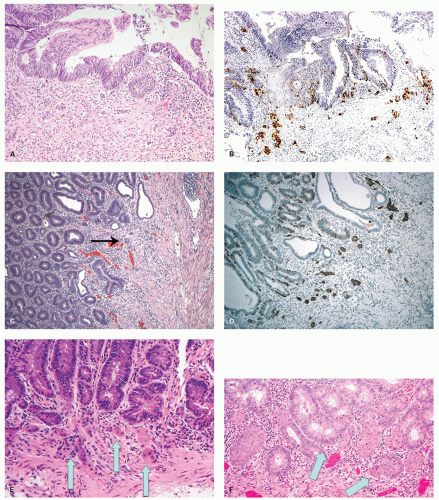

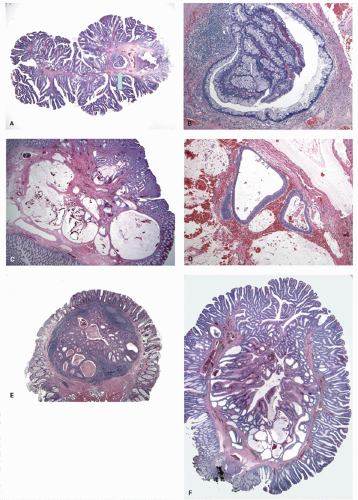

a) SSP with dysplasia: While regular SSPs lack cytologic dysplasia, they may develop it. The dysplasia may occur focally, but can also occur diffusely. It can be of the serrated type as described later or conventional type, and sometimes both can be present.

i) Serrated dysplasia: Serrated dysplasia is characterized by nuclei with open chromatin or vesicular nuclei with one or more small, but distinct nucleoli. This contrasts with the nuclei seen in typical adenomas in which nuclei are dense and hyperchromatic (

Fig. 20-26A,B). The degree of dysplasia is usually low grade, but these lesions may evolve into high-grade, intramucosal and invasive carcinoma through the same pathway, and often the cancer tends to retain the serrated architecture (

Fig. 20-26C,D). Infiltration can occur both through high-grade dysplasia (

Fig. 20-26G), but sometimes also directly from low-grade dysplasia, a feature that is both disconcerting and easy to confuse with the misplaced glands seen in HPs, except that the advancing edge is clearly infiltrative (

Fig 20-26H,I). Ectopic crypt formation (see

next section) is usually not seen although crypt budding that may be complex representing high-grade dysplasia may be present. Dysplastic SSPs are not infrequently found in combination with nondysplastic elements. We usually report all elements present, for example, SSP with low-grade dysplasia. If a comment can be made on completeness of excision, it is made, although often it is not possible, especially if the lesion has been removed piecemeal or with numerous biopsies. We suspect that the latter form of removal may result in higher local recurrence

rates, but as yet there are no data to support this.

ii) Conventional dysplasia (synonym: mixed serrated polyp and adenoma, tubular adenoma with serrations): These polyps are also identical to other nondysplastic serrated polyp but (

Fig. 20-26E,F) differ in having a focal area that is identical to that of a conventional adenoma.

128 The dysplastic area may or may not have the serrated architecture of the background

polyp but resembles an adenomatous polyp. This change can be seen within the serrated polyp or on its edges, as if the two lesions are collision tumors. The dysplastic nuclei tend to be more hyperchromatic and stratification is seen. Mitoses are increased. Progression usually occurs along the serrated pathway but may also progress through the microsatellite stable pathway. Dysplasia in conventional hyperplastic polyps (MVHP) or goblet cell hyperplastic polyps (GCHP) is vanishingly rare, but are mentioned previously and illustrated in

Figures 20-21C-E. Their significance is unknown. We suspect that they should be managed as other dysplastic serrated polyps.

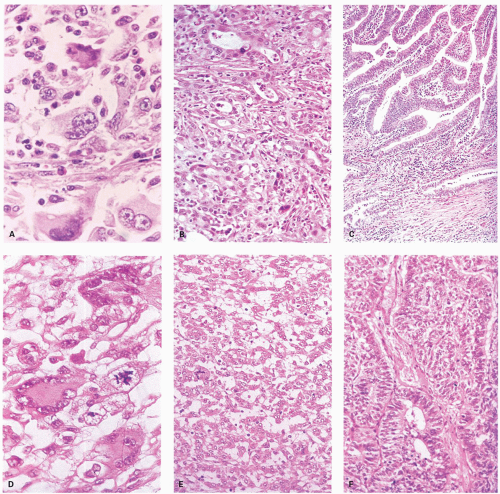

iii) Traditional serrated adenomas: These have a distinctive form of serrated dysplasia in which nuclei are more elongated than in usual serrated dysplasia, and is invariably accompanied by very tall cells with dense eosinophilic cytoplasm (see below).

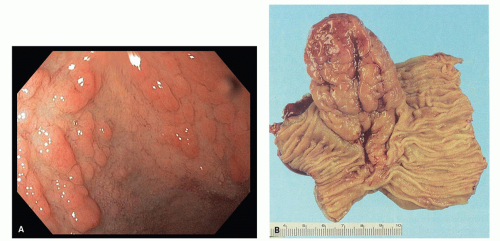

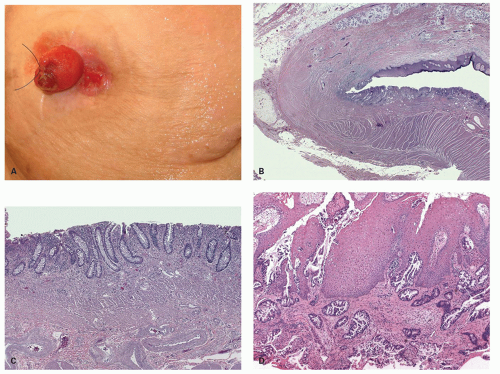

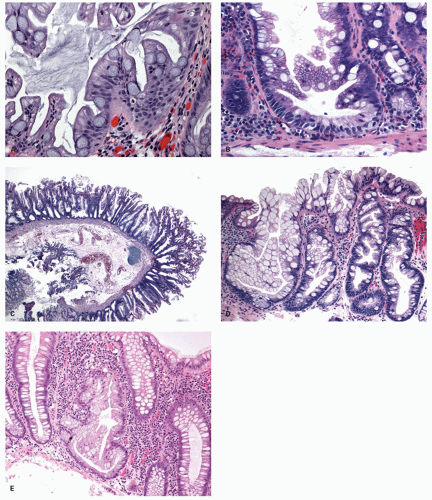

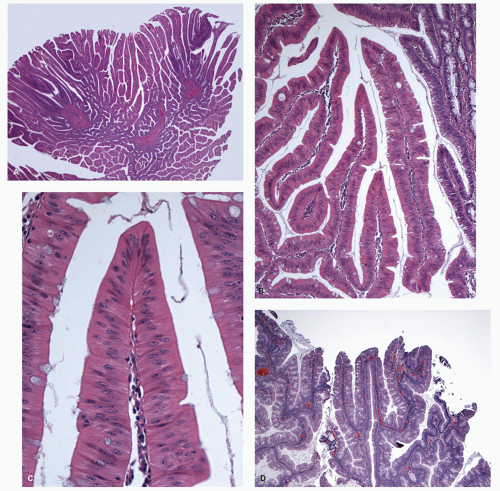

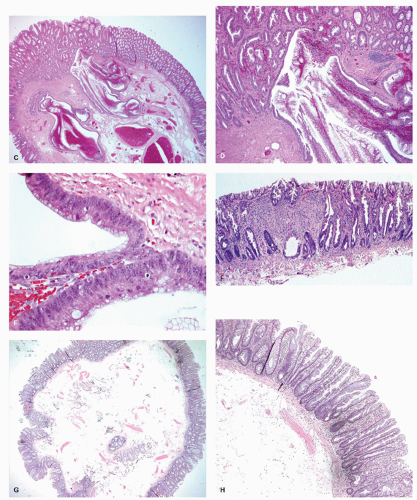

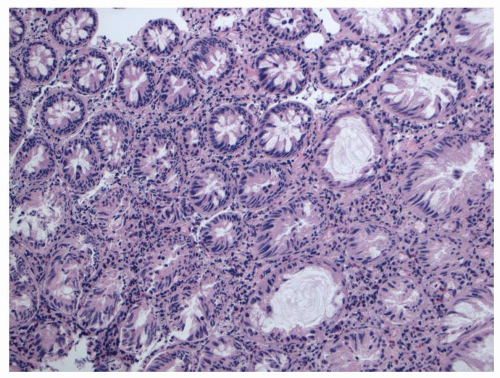

Traditional serrated adenomas. This lesion was first described by Longacre in 1990 as a serrated polyp with dysplastic features and distinct from HP and conventional adenomas, but is now referred to as TSA.

128,

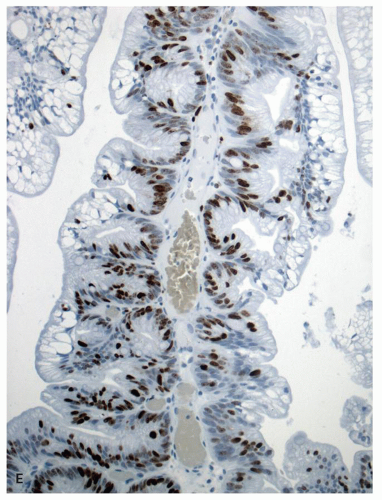

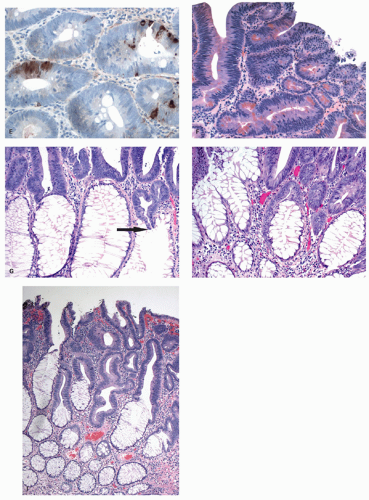

131 These were believed to be merely more advanced lesions in the serrated pathway, but they appear to be unique lesions that have distinct morphology and molecular phenotype. These are the least common serrated polyp, constituting <1% of all serrated lesions. These are distinct from adenomas as the proliferative index in the cells is lower, similar to other serrated lesions as shown with Ki-67 labeling.

151,

152 However, this pathway, despite morphologic similarities to SSP/HP seems to be associated with cancers that show low MSI (MSI-L that may give rise to more aggressive carcinomas).

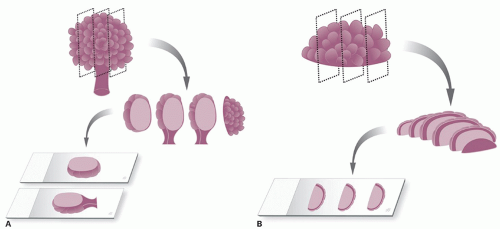

128 Formation of ectopic crypt seems to be a unique feature of these polyps and phenomenon responsible for their characteristic appearance.

151 As the concept of these polyps expands, the current definition may also include examples that are rich in goblet cells and lack the eosinophilic mucin-poor cells described in the original descriptions of the polyps. Filiform serrated adenoma is almost certainly a subset of TSA

128,

153; indeed a villous surface is often a characteristic of these polyps. Nevertheless, some are flat and sessile.

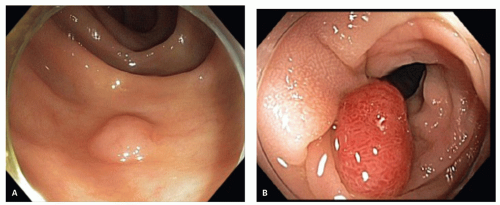

Clinical Features Although these tend to be larger than both HPs and SSPs, these are still not large enough to cause symptoms due to their size or any other complication. These occur much more commonly on the left side of the colon, and right sided TSAs while occur but are rare.

154

Gross and Endoscopic Features These are generally <1.5 cm size. The polyps are mostly sessile and tend to have a villiform surface. Occasionally these can be flat or focally show flat areas. Sometimes these are overtly polypoid. On gross and endoscopic examination, it is very difficult to differentiate these polyps from adenomatous polyps.

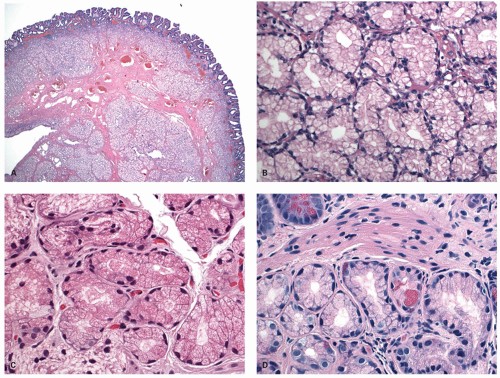

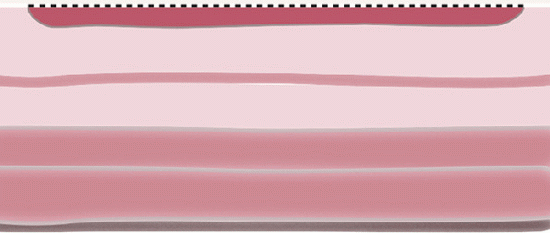

Histology The lesions often have a villiform architecture but are characterized by tall columnar cells that have intense pink eosinophilic, almost oncocytic cytoplasm, long pencillate nuclei and frequently ectopic crypt formation.

151 The nuclei are also typical of the serrated pathway, and are larger and more open and invariably have one or more small but distinct nucleoli. This contrasts with those seen in HP or nondysplastic SSP, as well as from the dense hyperchromatic dysplastic nuclei of conventional adenomas (

Figs. 26C,D and

20-27). Nuclear stratification is minimal to none, and the nuclei are generally lined up nicely in a single row almost at the same basal level within the cell. Mitoses are few and only rare or absent near the surface. However, one can see a range of changes, whereby some are difficult to differentiate from adenomatous dysplasia, especially with advancing grade of dysplasia. Sometimes the serrated architecture may be focal or subtle, and occasionally one may see a typical nondysplastic serrated polyp near its edges. Many of these completely lack goblet cell, while some have scattered goblet cells, and a few are composed of predominantly goblet cells. The architecture of the crypts can be complex, and indentations caused by formation of ectopic crypts that can be subtle or overt, and may represent accentuation of the serrations into new budding crypts. It should be recalled that adenomas grow and for new crypts by crypt budding both from the surface epithelium and the sides of crypts.

The “filiform” serrated polyp described with taller villi is now considered as a variant of TSA.

153,

155 The key feature that differentiates these polyps from the other serrated lesion is that the serrations result from two phenomena. One is similar to the other serrated polyps where the epithelium piles up as a result of decreased apoptosis, and the second mechanism is the ectopic crypt formation.

151 These ectopic crypts are seen as small aberrant crypts that dip down from (bud into) the villous surface, lack the perpendicular orientation to the surface, and fail to reach the muscularis mucosae (

Figs. 20-27D,E and

20-28E). These are considered ectopic crypts rather than mere invagination of the surface as they show a proliferative zone at their bases and a maturation pattern of the epithelium similar to regular crypts. The ectopic crypts help in the differentiation of TSAs from other serrated polyps with dysplasia and adenomatous polyps that lack them. Occasionally metaplastic bone formation has been reported within

these lesions.

156 Rarely similar lesions have been reported in the duodenum near the ampulla and in the stomach.

157,

158 The other cell types that can be present include endocrine cells and Paneth cells. Conventional villous adenomas also tend to have these nuclear features, as well as other features of TSAs such as the eosinophilic cytoplasm, serrations and ectopic crypts; however, currently it is stretching the envelope to suggest that they originate in other serrated tumors, although the similarity is difficult to overlook.

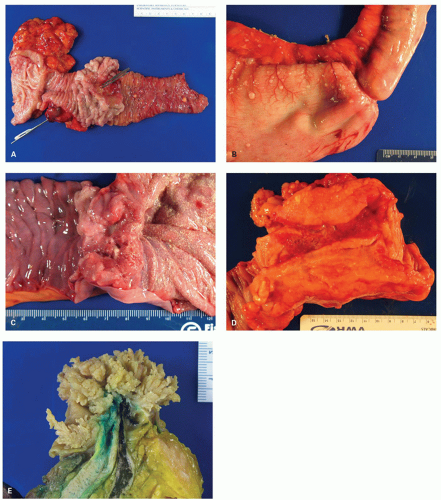

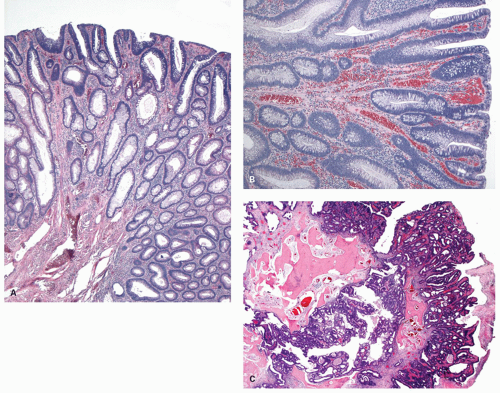

Unclassified serrated polyps. Unclassified polyps are those that do not easily classify into any of the described categories, or combinations of them, including the typical adenomas. Examples of some of those we have found virtually impossible to classify are shown in

Figure 20-29.

Immunophenotype and molecular pathology of serrated polyps. As discussed earlier the name HP is a misnomer as the rate of proliferation in these polyps is lower than normal, and the main defect is decreased apoptosis leading to decreased cell death and hence piling up of epithelium resulting in a wavy surface or serrations seen on sections. It appears that the serrations seem to move up the crypt in a spiral fashion, in a pattern virtually identical to that seen in flat small bowel biopsies.

159

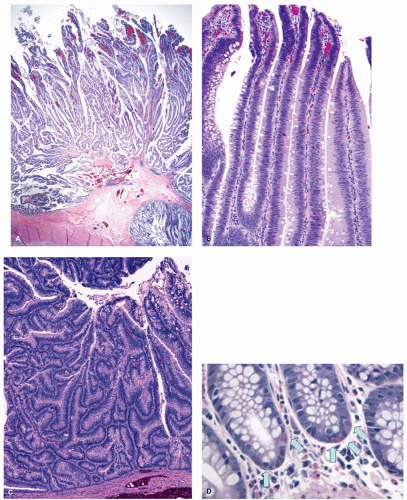

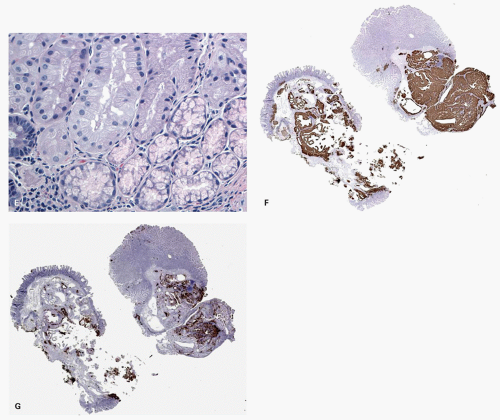

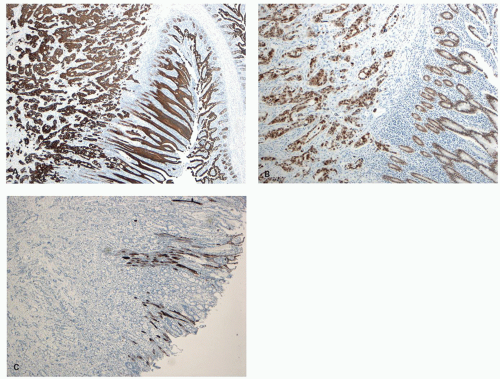

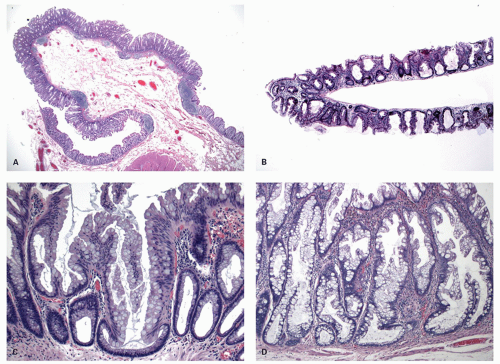

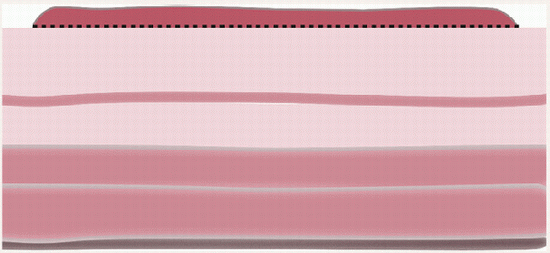

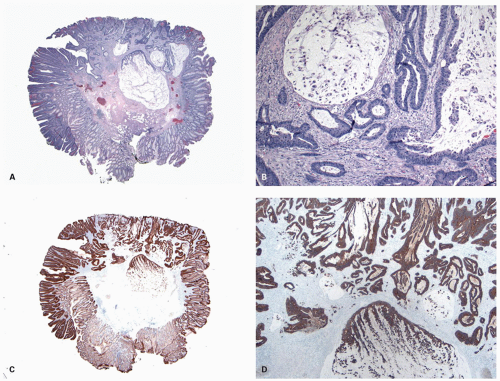

The study of proliferation zones and patterns of maturation of the epithelium in the crypts of HP, SSP, TSA, and conventional adenomas using Ki-67 and CK20 stains shows interesting patterns and explains some of the morphologic features seen in these polyps.

151,

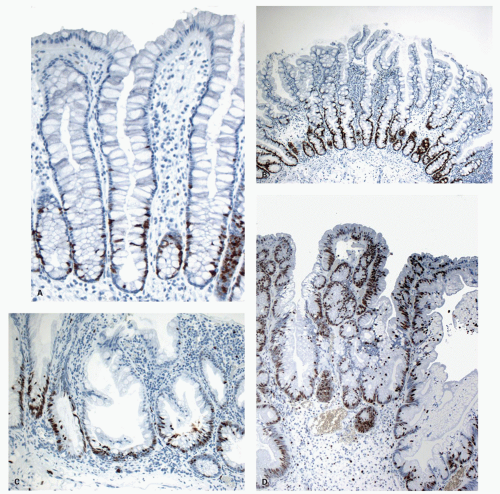

160 The HPs show the proliferative zone at the crypt bases in a symmetrical fashion similar to normal crypts (

Fig. 20-28A,B), and the maturation of this epithelium occurs fairly soon as it moves up the crypt as shown with acquisition of strong CK20 expression.

SSPs on the other hand have an asymmetrical distribution of the proliferative zone at the crypt bases, often pushed more to one side (

Fig. 20-28C,D). This likely explains the abnormal architecture at the crypt bases with horizontal growth pattern and abnormal shapes. The maturation of the epithelium is also aberrant, and mature goblet cells and CK20 expression can be seen at the crypt bases. The TSA shows proliferative activity toward the crypt bases somewhat similar to either SSP or HP, but also shows proliferation activity at the bases of ectopic crypts creating an asymmetrical pattern

151,

152 (

Fig. 20-28D,E). The surface seems to mature with CK20 positivity similar to other serrated polyps, even in the ectopic crypt foci. Interestingly,

the CK7 and CK20 expression in serrated lesions is different from normal colonic mucosa, as well as conventional adenomas and adenocarcinomas.

161 The serrated polyps often tend to express CK7, in addition to CK20, unlike normal colonic crypts and adenomas, which represents either the gastric differentiation or a more primitive phenotype.

161,

162 Consequently, the adenocarcinomas associated with serrated polyps also express CK7, in addition to CK20. Study of expression of mucin (

MUC) gene products has shown that serrated polyps often express gastric-type mucins, while conventional adenomas do not.

163Initially it was reported that expression of MUC6 (antral/pyloric gland-type mucin) may help to differentiated SSP from other types of serrated polyps; however, subsequent studies failed to confirm this specificity.

130,

163,

164 MUC6 expression in these studies has ranged between 82% and 100% of SSPs and 17% and 60% of HPs.

130,

163,

164 However, these studies did note a predominance of gastric phenotype in right-sided serrated polyps compared to the left-sided lesions, irrespective of the histologic type.

Cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 expression in serrated polyps also shows differences from adenomas.

165 In one study, 71% of TSAs showed moderate to strong positivity for COX-2, while only 32% of nondysplastic serrated polyps showed weak to moderate positivity.

166 Expression of p53 and AMACR (P504S) has also been reported to be different in TSAs compared to nondysplastic serrated polyps. TSAs tend to show a diffuse positivity for p53 and AMACR, while SSPs and HPs show focal and weak positivity, which is limited only to the basal half of the crypts, especially the lower one-third in the HPs.

167 While the utility of these markers in clinical practice is yet unclear, they certainly support the view that TSA is a lesion distinct from other nondysplastic serrated polyps as well as conventional adenomas.

A variety of genetic and epigenetic modifications occur in the serrated pathway that are distinct from the adenomatous pathway. However, within the serrated polyps, there are distinct differences between various subgroups (

Table 20-4).

128 There is some overlap as well, which pertains to either lack of strict diagnostic criteria or some biologic relationship between different subtypes, or a combination of both. It is most interesting that despite the variations between different types of serrated polyps, the most striking difference occurs in the right- versus left-sided polyps, irrespective of the polyp subtype.

147 This lends support to the speculation that right-sided colon cancer may be a different disease compared to left-sided cancers, irrespective of the precursor lesions.

Most of the MVHP and SSPs show activating mutations in the BRAF gene, while most of TSA and GCHP show mutations in KRAS.

138,

147,

168 BRAF is a proproliferative and antiapoptotic serine-threonine kinase, which explains many of the features of serrated polyps. Interestingly, the MVHP and SSP that occur on the left colon show more often KRAS mutations compared to right-sided lesions, similar to TSA and GCHP.

SSPs are also prone to methylation of a number of key genes, most importantly MLH1 that leads to MSI.

168 Methylation of MLH1 and MSI is seen only with development of cytologic dysplasia in SSPs. The progression of SSP to MSI-high cancers likely occurs via this pathway.

169 It is speculated that MVHP may be an early precursor in this pathway, which progresses to SSP, and subsequently develops dysplasia before developing into an invasive carcinoma.

147 It is recognized that SSPs are also associated with the development of MSS CRCs.

In CpG island-methylated carcinomas (see later), however, the sequence of events and genes involved in the progression of BRAF-mutated SSP to carcinoma is unknown. It is widely suspected that once dysplasia develops in serrated polyps, the progression to invasive carcinoma probably occurs more rapidly

compared to the adenomatous pathway, while progression from an MVHP/SSP to dysplastic serrated polyp takes much longer.

128 One report suggested development of an invasive cancer in an SSP within 8 months.

170 The limitation of this report is that there is no histologic confirmation that at the time of initial diagnosis, there was no cancer.

TSAs as currently defined by the WHO appear to have KRAS but not BRAF mutations.

138,

171 These are not associated with hypermethylation of MLH1 or CIMP-high MSI cancers, but give rise to MSI-L cancers, often simply being included as MSS.

128,

172 Since GCHPs also occur predominantly in the left side and have mostly KRAS mutations, one can speculate whether they are the precursors of TSAs, which not infrequently have areas resembling GCHP at the periphery of the lesion.

Interobserver variability. This remains a major area of concern in the field of serrated polyps. Studies evaluating interobserver variability have shown that in general, the agreement between pathologists regarding diagnosis of serrated lesions is poor to modest even among expert GI pathologists with special interest in this area.

173,

174,

175 In one study of 60 cases of various serrated lesions reviewed by four specialist GI pathologists, complete agreement was seen only in two-fifth of the cases.

176 The overall concordance in the study was considered moderate (

k value = 0.49). When the studies involve individuals from the same institution, similar training, or practice group, the agreement is likely to be better. Lack of standardized criteria, rapidly changing concepts and terminology, and lack of any discriminating special stains have led to wide variation in the proportion of SSPs diagnosed in various groups even within the same geographic area or within the same institution by different pathologists. Further, when pathologists are unsure whether to use HP or SSP, should they check the site of the polyp and find it was in the right colon, the bias will be towards SSP, whereas if the same polyp was in the recto-sigmoid the bias would be towards an HP. Such are the vagaries of expectation bias (or our modification of it).

Differential diagnosis and approach to diagnostic problems. The diagnostic problems are twofold: First, to reliably separate serrated polyps from other mimics and then to properly subclassify the serrated polyps.

(i) Differentiation of serrated polyps of various types: Separation of MVHP from GCHP or MPHP is not much of a problem due to fairly distinct histology, and since in current clinical practice, it is not required to report the subtypes of HP, and it is also not a practical issue. The major issues are with the differentiation of SSP from MVHP, which very much affects subsequent management, and differentiation of SSP from TSA, which probably does not as both are considered preneoplastic. Much of this problem arises from rapidly changing terminology and lack of standard guidelines as to the minimal criteria for each entity. However, as the molecular pathology of these lesions becomes clearer, the classification and the histologic criteria have also become more refined. The current WHO classification is the best guide for the terminology and the histologic criteria for these lesions is shown in

Table 20-3.

The differentiation of SSP from MVHP can be difficult (

Tables 20-5 and

20-6). Since MVHPs so frequently have a small part, even a single crypt, that could be considered an SSP, it becomes highly subjective as to how much of an HP needs to be SSP-like to change the diagnosis to SSP. Whether the presence of one abnormal crypt is enough to make a diagnosis of SSP or what feature should trigger

deeper levels in MVHPs is a question that is unanswered at this time. It is not without consequence as the change in diagnosis from HP to SSP changes the follow-up interval. Our approach is that if any of the architectural abnormalities described with SSP (basal dilatation, horizontal growth pattern, architectural distortion, and basal serrations) are present unequivocally, it is sufficient to make this diagnosis, even if it involves only one crypt. Of these, architectural changes and particularly a horizontal growth pattern is probably the most specific and easily identified. If other features are present without the architectural changes, or when the architectural changes are equivocal, it is justified to get deeper levels, if it affects the follow-up interval in the patient. Without the architectural features present, we are reluctant to make the diagnosis of SSP. It also seems justified to get serial sections if the initial sections of a large HP, especially on the right side fail to show any features of SSP. For such lesions in the right side, our threshold for calling them SSP is low. In this regard, use of any special stains or molecular analysis is currently not recommended for clinical purposes.

Differentiation of SSP from TSA is less of a problem, as the morphology of TSA has been better defined and the group of SSP with dysplasia (serrated or adenomatous) has been clearly been separated from TSA. Villiform architecture and diffuse nuclear atypia that is typical of TSA are not seen with SSAs. However, some serrated polyps with the typical architecture of SSP have very eosinophilic cytoplasm, marked serration, pencillate nuclei, and low-grade serrated dysplasia, identical to features seen in a TSA but without any ectopic crypts. We would like to call these as SS with serrated dysplasia, although until a newer classification of serrated polyps becomes established and accepted, and their molecular pathways become better delineated, one has to accept that this is somewhat arbitrary. The presence of ectopic crypts, which only are rarely seen in the SSP might lead to a diagnosis of a combined polyp. The presence of focal dysplasia, but no other features of TSA, should put these lesions into SSP with dysplasia category and not TSA.

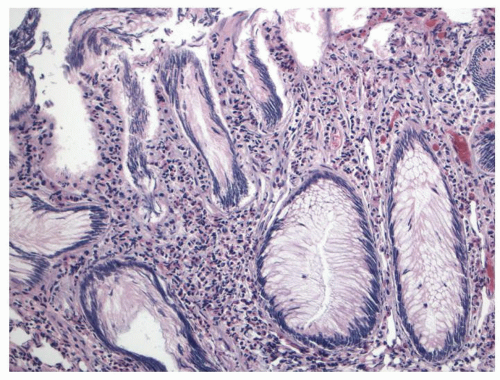

(ii) Differentiation of serrated polyps from other mimics and other diagnostic issues: It should be remembered that although the serrated appearance of the crypts is characteristic of HPs, this appearance is frequently seen in crypts immediately beneath surface granulation tissue of other polyps (

Fig. 20-29C,D), particularly in ulcerated juvenile or inflammatory polyps but also in mucosal prolapse with ulceration (solitary rectal ulcer syndrome [SRUS]) and sometimes even in adenomas. With the exception of nonulcerated adenomas, this appearance should not lead to attempts to classify such polyps as “combined” polyps, as it seems to be a nonspecific feature of epithelium growing into granulation tissue.

Diathermy artifacts: This can cause difficulty because the lesion may not be diagnosable if the artifact is too severe. In addition, the stringing artifact of nuclei can make the nuclei hyperchromatic and larger, resulting in misinterpretation as an adenoma (

Fig. 20-30). When the changes are marked, interpretation should be avoided with a comment like “marked cautery artifacts preclude proper classification of the polyp.” If the diathermy changes are mild, the best interpretation is given, and one may suggest in the report that the diagnosis is difficult because of changes induced by the diathermy.

Mucosal prolapse and mucosa at the distal rectum or anorectal junction: One of the areas where considerable confusion can occur is in the distal rectum or anorectal junction, where mucosal prolapse or SRUS, can mimic serrated polyp, and at least in parts the morphology could be indistinguishable from a serrated polyp (

Fig. 20-31). The proliferation of smooth muscle in the lamina propria cannot be used as a sole differentiating feature as some of the serrated polyps, especially in the distal colon, can acquire this feature. The overall features in the mucosal prolapse still are distinct with more disorganized crypts, the presence of superficial erosions, or ischemic-type features, sometimes with adenomatous-looking glands along with fibromuscular hyperplasia in the lamina propria. In this setting, the diagnosis of serrated polyp should not be made purely based on the presence of few serrations in some crypts but should also take into account absence of mucosal prolapse-type features. One study of 26 cases of SRUS with serrated crypt architecture showed loss of staining for MLH1 in the superficial cells, similar to SSPs in the control group.

177 BRAF and KRAS mutations were not evaluated in this study. This does beg the question if these indeed represent distally located serrated polyps with superimposed features of mucosal traction; however, this needs to be further studied before drawing any conclusions.

Hyperplastic polyp versus carcinoma: HPs may occasionally erroneously be misinterpreted as superficial biopsies of carcinoma. The bases of the glands may be caught up in the underlying thickened muscularis mucosae or sometimes have an inverted growth pattern whereby crypts continue to grow below the level of muscularis mucosae. While the differentiation is fairly easy when the entire lesion is seen and the lesion lacks any cytologic atypia, when changes mimicking adenoma are present at the crypt bases with hyperchromatism and mitoses (

Fig. 20-32A,B), especially in small and poorly oriented biopsies, there is a potential for misinterpretation. Awareness of this phenomenon and discussion with the clinician, which would often reveal that the entire lesion is barely a few millimeters in diameter and endoscopically looks like a benign polyp, should help in preventing this error. This issue can be more problematic in some of the larger pedunculated serrated polyps that develop misplaced glands in the polyp stalk (pseudoinvasion), especially when these misplaced glands show nuclear atypia and/or extravasated mucin (

Fig. 20-32C,D,F). There is no evidence that these are malignant or carry any risk of nodal metastasis, and polypectomy is curative. However, one need to be careful as invasive carcinomas can arise in serrated polyp, and can be quite subtle (

Fig. 20-26), and the key is to look for unequivocal features of invasive carcinoma similar to those in adenomatous malignant polyps as discussed later.

Serrated polyp and associated mesenchymal tumors. An unexplained phenomenon is the association between serrated polyps and especially benign fibroblastic polyps/perineurioma which may be mucosal, submucosal, or both (

Fig. 20-32F), both of which may be associated with BRAF mutations (see

Chapter 7). More common are serrated polyps with underlying lipomatous lesions (

Fig. 20-32G,H) (also described in

Chapter 7).

Treatment and follow-up. The serrated pathway is believed to lead to up to 30% of all CRCs, mostly via

SSPs, and this has led to new approach to management of these polyps.

169 The HPs are thought to have minimal risk of progression to colon cancer, and guidelines for their management have not changed much over the years.

178 These should be removed completely and sent for histology when feasible. When these are in distal large bowel, diminutive (<5 mm) and many, it is reasonable to biopsy 6 to 8 polyps to confirm that they are just HPs. As long as these are all HPs, there is no change in screening for colon cancer protocol or in the interval for colonoscopic surveillance. There are no specific guidelines for larger HP (>1 cm); however, as we have learned that many of these especially on the right side are SSPs, these should be completely removed and adequately evaluated with serial sections.

FOLLOW-UP OF SERRATED LESIONS. Two groups have proposed suggestions for follow-up of serrated lesions, and both are similar.

179,

180 The AGA has proposed follow-up guidelines whereby the surveillance once the lesions are completely excised is every 5 years for smaller SSPs (<10 mm) and every 3 years for the larger (≥10 mm) and dysplastic SSPs (

Table 20-7).

180 The surveillance period is much shorter, that is, 1 year for those with serrated polyposis syndrome. However, it should be recognized that these suggestions are merely based on predicted behavior of these lesions without any long-term outcome studies and have not yet been validated. It has been speculated that the progression from MVHP to serrated polyp with dysplasia possibly takes many years, while the progression to invasive carcinoma may be very rapid once dysplasia develops, even compared to adenomatous pathways.

169,

181 This also stresses the need to keep the identity of this pathway distinct from adenomatous pathway while designing the classification schemes and nomenclature.

Large Bowel Adenomas

Definition. An adenoma is a benign intraepithelial neoplasm composed of dysplastic cells. If dysplastic mucosa is not visible as a gross or endoscopic lesion, it is simply called

dysplastic mucosa or sometimes

flat adenoma (see subsequent discussion), while in IBD it may also be called “invisible dysplasia”. By conventions, these dysplastic lesions that form a polyp or discrete lump are called adenomas, although in idiopathic IBD, these are sometimes referred to as a dysplasia-associated lesion or mass or adenoma-like mass

182 (see

Chapter 18). As discussed in the previous section, adenoma is sometimes used for non-dysplastic serrated lesions (SSA) as well.

Age, sex, and distribution. In the first two or three decades of life, adenomas are extremely uncommon unless the patient has some form of inherited syndrome such as familial polyposis, rarely constitutional (biallelic) mismatch repair deficiency syndrome, or a juvenile or other polyp that has become dysplastic. About 5% of adenomas occur in the fourth decade, 15% in the fifth decade, and about 30% each in the sixth and seventh decades (50-70 years of age). Most of the remainder appears in the eighth decade, and only about 2% became manifest clinically after this time.

183 The incidence of adenomas rises continually with age, and always has a slight male predominance, although these figures vary, depending on whether polyps present with clinical symptoms or are found incidentally at colonoscopy or autopsy. Nevertheless, in high-incidence countries for CRC, 25% to 50% of the population will have adenomas at autopsy.

134,

140,

141,

184,

185,

186,

187,

188 In low-incidence countries, adenomas are rare.

134 It has been estimated from autopsy data that by the age of 50, about 60% of men and 40% of women have an adenoma.

189

The distribution of adenomas within the large bowel also depends on the method of detection and reporting. In some series, there is a tendency for a large proportion of adenomas to be rectosigmoid. For instance, in one large study from 1978 to 1982 (when colonoscopy was not universal, bowel preparation was suboptimal, and flat adenomas were not generally recognized), 29.1% of polyps were rectal, 31.5% were sigmoid, and the remainder were distributed fairly evenly around the colon. Thus, 10.5% were in the descending colon, 3.8% at the splenic flexure, 9.2% in the transverse colon, 3.4% at the hepatic flexure, 9.3% in the ascending colon, and 3.3% in the cecum.

183 There is increasing evidence of a relationship between age and distribution, distal adenomas occurring in younger patients and more proximal adenomas in

older ones.

139,

190,

191 The apparent shift of adenomas from the rectosigmoid proximally may in part reflect colonoscopists awareness or radiologic detection in an older population that has already selected itself for examinations. Also, use of better bowel preparation methods and advanced colonoscopic techniques (NBI, high resolution, etc.) have increased the detection of right-sided polyps. Once the bowel has been “cleared” of polyps endoscopically, there is a relatively uniform distribution of adenomas, with, if anything, a peak in the right or transverse colon.

140,

141,

192Diminutive Polyps These are defined as polyps up to 0.5 cm in diameter.

193 At this size, the clinicopathologic correlation between endoscopic or gross appearance and histology is poor. Approximately 40% to 60% of diminutive polyps prove to be hyperplastic; 25% to 40% adenomas; 15% to 20% contain only normal mucosa (unrecognized GCHP, the endoscopist missed a lesion, the pathologist missed the lesion, or the lesion was not on the slide); 7% are inflammatory; and 2% are largely fibrous tissue.

193,

194 It is theoretically possible to destroy these with diathermy, but many consider it too time consuming, particularly as some patients may have dozens of lesions in the 0.2- to 0.3-cm range especially in the rectosigmoid, and possibly unnecessarily increasing the risk of thermal injury to the bowel. Many of these lesions do not grow, or grow slowly, but some regress.

194 The eventual outcome is likely related to the true nature of the polyp. Although most diminutive adenomas have only low-grade dysplasia, some have high-grade dysplasia, including carcinoma in situ (CIS), which may be interpreted as “de novo carcinoma.” As with adenomas, provided that the patient does not have a coagulopathy or is unlikely to survive for more than a year or two, it seems reasonable to destroy or remove all diminutive polyps. Hot biopsy forceps destroy the lesion and provide material for histology—the tradeoff sometimes being coagulation artifact in the tissue and complete destruction of the lesion. If any of these polyps prove to be adenomas, some form of long-term follow-up may be desirable.

Natural History of Adenomas This is discussed with the growth kinetics of colonic carcinoma.

Synchronous and Metachronous Adenomas There is considerable evidence that patients with one adenoma are likely to develop additional adenomas, which will probably be in the same part of the large bowel as the index polyp rather than distributed randomly throughout the remaining large bowel.

136,

195 Further, the larger and more dysplastic the index polyp (including invasive carcinoma), the more likely are additional polyps to be present.

Patients with larger, more dysplastic, and multiple adenomas are at greater risk of developing further multiple, large, or dysplastic polyps and carcinoma.

196,

197,

198,

199 The greatest risk factor for proximal “advanced” adenomas (>1 cm and/or a villous, component, and/or high-grade dysplasia) is distal advanced adenomas; the presence of proximal neoplasms with high-grade dysplasia or cancer was significantly correlated with the presence of advanced rectosigmoid adenomas. In one study proximal advanced neoplasms were detected in 11 (20%) of the 55 patients with advanced and in none of the 45 patients with nonadvanced, rectosigmoid adenomas (odds ratio: 23.5).

200 In a second study, patients with advanced lesions on sigmoidoscopy had a 10% prevalence of an advanced proximal lesion on colonoscopy, but patients with small (≤1 cm) tubular adenoma(s) on sigmoidoscopy had a 1% occurrence of an advanced synchronous lesion. However, in this study, HPs seem not to be a good predictor of proximal adenomas.

201 In a well-controlled study of patients with distal HPs, tubular adenomas, and advanced polyps, the likelihood of having advanced proximal neoplasms was 4.0%, 7.1%, and 11.5%, respectively.

202 However, half of the patients with advanced proximal lesions had no distal lesions, so these data are unlikely to have management implications regarding the potential frequency of follow-up endoscopy. In patients with CRC, there is a much higher prevalence of synchronous lesions; one careful study found that synchronous benign polyps were present in 30% and synchronous cancers in 5%.

203In estimating the development of new polyps, the possibility that polyps may have been overlooked at the initial colonoscopy must be taken into account. The miss rate of adenomas in various studies varies between 6% and 27%, even when adjusted for the quality of colonoscopy.

204,

205 For this reason, polyps measuring 1 cm or more detected within 12 months of the initial colonoscopy are assumed to have been present or incompletely removed at the previous endoscopy.

206 In patients who underwent removal of “all” index polyps, one-half were subsequently found to have additional adenomas in several studies,

188,

207,

208 and the likelihood of new adenoma formation is probably increased in patients who had multiple polyps initially. For example, in one study, 70% of patients with multiple adenomas developed further adenomas compared to 35% of those with single adenomas.

188 Nevertheless, the rate at which new adenomas are found tends to decrease with further endoscopy, suggesting that adenomas may occur in crops.

Increased Risk in Patients with Inherited Colorectal Carcinoma Syndromes While it is self-evident that patients with FAP develop numerous adenomas, those with HNPCC/Lynch syndrome are also at increased risk. The risk of multiple primary carcinomas is 7% to 18%, and the development of metachronous tumors

is 3% per annum.

209,

210 Patients with HNPCC appear to go through the adenoma-carcinoma sequence faster than other patients, possibly in 2 to 3 years, presumably the result of the additional defects in mismatch repair genes being present.

211,

212

All of these data point to an obvious conclusion that patients with one large bowel neoplasm, whether an adenoma or a carcinoma, are prone to develop new neoplasms at an increased rate. Clearly, what is important is whether these will translate into invasive carcinomas if not continually removed, and whether removal of polyps as they form will eliminate this risk. It is also known that 4% to 8% of patients who develop invasive CRC will subsequently develop a second (metachronous) carcinoma.

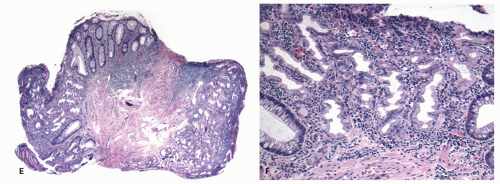

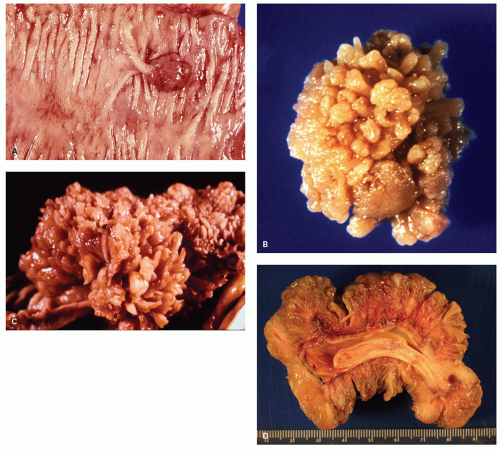

Gross and Endoscopic Appearances The endoscopic and gross appearance of the polyps has now been classified as per the new Paris classification (

Table 20-8) and varies with size of the lesions (

Fig. 20-33).

213 The Paris classification applies to all adenomas and early carcinomas (mucosal and submucosal cancers). The range of small lesions is best appreciated in patients with FAP. When polyps are small, measuring a few millimeters, they may have the same hue as the background mucosa; it is then impossible to predict the histology of the polyp accurately, and these are sometimes only visualized with either dye-spray techniques, NBI, or high-resolution endoscopy. The smaller lesions consist of a barely discernible mucosal bump that may or may not have a reddish discoloration because of mucin depletion, possibly increased vascularity, superficial ulceration, or hemorrhage within.

Some polyps are flat or sessile and barely raised above the background mucosa. The term depressed adenoma is sometimes used; however, it is usually a misnomer as they are slightly raised above the background mucosa but do have a central depression. Some adenomas do appear to be truly depressed below the level of the adjacent mucosa, and this term seems quite appropriate for these. They are discussed subsequently.

When polyps enlarge, they may grow in a variety of ways that are not mutually exclusive, but rather show considerable overlap. At one extreme, they grow on a thin stalk (pedunculated) (

Fig. 20-34); at the other, they become progressively broad based or sessile (

Fig. 20-34). In some sessile lesions consisting of tubular architecture, the appearance may be that of a barely distinguishable raised plaque.

214,

215 The development of villi or papillary fronds produces a much thicker mucosa, which therefore is raised well above the background mucosa. Fronds result from the development of large grooves in adenomas, each groove surrounding groups of crypts.

216 Sometimes huge circumferential adenomas develop, particularly in the distal large bowel.

Most polyps are tubular adenomas that are <1 cm in diameter, but with increasing size there is a significant increase in the villous component. For example, in one large endoscopic series, about two-thirds of the adenomas were 1 cm or less in diameter; of these, 90% were tubular, 9% tubulovillous, and 1% villous adenomas. About 20% were 11 to 20 mm (54% tubular, 42% tubulovillous, and 4% villous adenomas); 6% were 21 to 30 mm (21% tubular, 67% tubulovillous, and 12% villous); and the remaining 10% were larger than 3 cm (17% tubular, 48% tubulovillous, and 35% villous).

183Histology Adenomas are characterized by the presence of dysplastic epithelium (

Fig. 20-35). The dysplastic changes are characterized by nuclear changes and tend to follow one of two pathways. The more usual consists of enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei that have some degree of stratification, of which there is a broad spectrum (

Fig. 20-35C). A second but overlapping pathway consists of nuclei that tend to be more open and vesicular, often with small but easily visible nucleoli and eosinophilic cytoplasm (

Fig. 20-35D). These changes resemble the nuclear changes seen in serrated dysplasia, especially when only low-grade dysplasia is present. The dysplastic nuclei are frequently enlarged to a degree that without significant nuclear overlap or stratification, they occupy more than half of the cell. Loss of polarity is frequent, and similar changes are readily found in most invasive carcinomas. Rarely, large pleomorphic bizarre nuclei may be seen in the background of an otherwise uniform population of cells with low-grade dysplasia simulating virally infected cells (

Fig. 20-35F). This change is of unclear nature and should not change the overall grading of the adenoma.

The nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio is increased, and the cells often contain only scant mucin or are completely devoid of mucin, which imparts a basophilic hue to the entire cell at low magnification. Combined with the cytoplasmic staining and presence of enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei, the dysplastic epithelium appears more bluish compared to normal epithelium, a feature that is easy to recognize even with a quick superficial look at low magnification (

Fig. 20-35A).

The number of mitoses is usually increased, and often mitoses are seen near the top part of the crypt or at the surface. Another feature that is often present in dysplastic epithelium, but rarely in regenerative/reactive epithelium, is the presence of increased apoptotic debris along with increased mitosis (

Fig. 20-35C). These can be very prominent, being first described by Leuchtenberger in 1956.

Besides the cytologic changes, architectural changes also occur, especially with increasing grades of dysplasia that are often also easy to spot on low

magnification. Well formed architectural changes are one of the characteristic features of high grade dysplasia. At the earliest stages, the tubular architecture of the crypts is maintained, although the crypts are wider and slightly larger (

Fig. 20-35), so that two populations of crypts are apparent, usually one of larger crypts with a rim of larger more prominent hyperchromatic nuclei compared to the residual normal crypts. Less commonly the crypts are of the same size but the nuclear changes are apparent. Morphologically it is apparent that adenomas grow in size by three main mechanisms: a) cells, and therefore crypts increase in size b) crypt budding and fission c) surface extension over and into neighboring crypts (crypt cannibalism), often apparent by junctions between dysplastic and non-dysplastic mucosa.

With progression, the crypts not only become larger and wider, the shapes change with budding or crypt fission, leading to irregular or “cauliflowershaped” crypts. This is a more overt form of the ectopic crypts seen in the traditional serrated adenomas previously discussed.

More advanced lesions reveal decreased stroma between the crypts, more compact arrangement of dysplastic crypts approaching a cribriform architecture (see

Fig. 20-39). The presence of luminal dirty necrosis with cribriform architecture suggests progression to intramucosal carcinoma. Another feature is that in most adenomas the maximal changes are present at the surface and it appears that the dysplastic epithelium is growing from the surface down to the bottom of the crypts, so-called “top down dysplasia” (

Figs. 20-35A and

20-72C). This is most obvious at the edges of the lesion (see later formation of adenomas), while in the center of the lesions, the entire length of the crypts appears to be involved.

While most of the adenomas have tubular growth pattern, some have a villous component as well and some are predominantly villous. The villous adenomas tend to be larger and can be sometimes be lined by hypermucinous epithelium. In contrast to the tubular adenomas that show a “top down” growth pattern, villous adenomas tend to show maximal dysplasia at the crypt bases (bottom-up dysplasia, that tends also to characterize serrated dysplasia), with variable degree of maturation that can sometimes cause confusion (

Fig. 20-36A-C).

The cells comprising most of the adenomas are mucin-depleted columnar cells that mimic undifferentiated progenitor cells near the crypt bases (

Fig. 20-35A). Some adenomas appear more mature with varying amounts of goblet or mucin-containing cells, while some are clearly hypermucinous (

Fig. 20-35E). Rarely the same type of clear cell change that occurs in dysplasia in colitis is found in adenomas (

Fig. 20-37C,D). This change is mucin negative and may be indicative of glycogen, but may also represent enteroblastic differentiation. It may sometimes cause diagnostic problems with metastasis, for example, from a renal clear cell adenocarcinoma.

217Among other cells, endocrine cells are readily found in adenomas, which can be easily highlighted using endocrine markers. Immunoreactivity to a variety of peptides, including glucagon, serotonin, pancreatic polypeptide, gastrin, and somatostatin, can sometimes be demonstrated. For the main part these reflect endocrine cells normally present in the intestines. While some can be recognized easily by the presence of characteristic fine eosinophilic granules, some can only be appreciated with special stains or IHC (

Fig. 20-36D,E). The incidence of endocrine cells tend to be higher in adenomas of the distal colon and the rectum than that of the proximal colon, with a second

peak in those from the ascending colon.

218 Occasionally single cells containing both mucus and endocrine granules are suggestive that amphicrine differentiation can be seen. There is no apparent association between the presence of endocrine cells with any other clinical or histologic parameters.

219Paneth cells are not uncommon in adenomas; however, the reported incidence varies from 0.2% to 32%.

220,

221 When present they tend to be located toward the crypt bases (

Fig. 20-36F). Although Paneth cells are normally found in the right colon, in adenomas they tend to be found more commonly in the left-sided polyps.

222 Paneth cells occur primarily in adenomas with low-grade dysplasia and in villous adenomas.

220 Paneth cell-rich adenomas occur both in polypoid and flat polyps, although there is no apparent clinical significance attached.

223Another finding that may be sometime seen in colonic adenoma and can be confusing is squamous metaplasia. This is said to occur in 0.44% of adenomas.

222 It appears as well-differentiated nests of cells budding from crypts either into the lamina propria or, more usually, into the crypt lumen (

Fig. 20-37A,B). It tends to have a left-sided distribution and may be found at the surface or base of the crypts. It is of academic interest only. Similar changes may also be found in adenocarcinoma.

A variety of changes occur in the lamina propria that can sometime dominate the morphology. Bleeding in adenomas is usually reflected by dilated capillaries or hemorrhage in the lamina propria, primarily close to the luminal epithelium; it can involve the muscularis mucosae and extend into the submucosa (

Fig. 20-38B).

224,

225 Hemorrhage resolves with the formation of hemosiderin pigment, which is frequently present in the lamina propria. Polyps most likely to bleed are those that are pedunculated, have a villous growth pattern, and are >1 cm in diameter; they are usually in the sigmoid colon. This is unrelated to the degree of dysplasia; however, in one study proximal polyps were said to be more likely to show evidence of old hemorrhage than distal polyps.

225Smooth muscle may be a significant component of adenomas and may cause considerable confusion. In polyps of virtually any type, the muscularis mucosae is thickened, and fibers from it may extend up between the bases of the crypts, usually in between the adenomatous crypt like a teeth of a comb (

Fig. 20-38A). This is similar to the changes with mucosal prolapse and should not be confused with arborizing muscle bundles seen with Peutz-Jeghers polyps. This may also give a false impression of invasion, especially in tangential sections.

226 In pedunculated polyps, these secondary changes of thickening of the muscularis mucosae, submucosal fibrosis, and blood vessel proliferation, thickening, and ectasia may virtually obliterate the submucosa; this may be a problem where invasion is suspected. In this situation, the “line” between the muscularis mucosae and submucosa becomes indistinct and may be so poorly defined that the presence of very early submucosal invasion is virtually impossible to assess. Fortunately, metastases only seem to occur with obvious submucosal invasion, and even then rarely; under these circumstances, we state simply that unequivocal invasion of the submucosa is not demonstrated and, provided that local excision is complete, no further treatment is necessary.

Tubular versus Villous Patterns of Growth It is conventional to describe adenomas in terms of their low power microscopic growth pattern. Classification

of adenomas into tubular, tubulovillous, and villous is not very reproducible other than for pure tubular adenomas. The term villous can be used both macroscopically for fronds (

Fig. 20-34); macroscopically these fronds form “villi” that are hugely thick and bulbous that are visible looking grossly at the slide. These contrast with more intestinal type villi we tend to think as villi microscopically. The notion that with this ambiguity we can accurately estimate the amount of villousness, and separate those just less than 25% or 75% (the dividing lines of tubulovillous from tubular at one end and villous at the other) is of course totally absurd. However, adenomas with no villi are easy and those with villi of some sort similarly easy, while the remainder have no clinical significance as “a villous component” of any sort puts an adenoma into the “advanced” category.

619 However, most pathologists classify adenomas, and most endoscopists or surgeons expect it. On the whole, the subtype of adenoma corresponds reasonably well to endoscopic or macroscopic appearance, so that the microscopic appearances are often predictable from the gross appearances. Because adenomas constitute a spectrum of changes, they are conventionally classified as follows:

Tubular Adenoma An adenoma in which dysplastic crypts occupy at least 75% of the tumor, while some degree of villous component, up to 25%, makes up the remainder. Most usual large bowel adenomas are tubular. This definition also includes the variants called flat and depressed adenomas discussed subsequently.

Villous Adenoma An adenoma in which at least 75% of the tumor is composed of leaf- or finger-like processes of lamina propria covered by dysplastic epithelium, up to 25% of the remaining adenoma being made up of dysplastic tubular adenoma.

Tubulovillous Adenoma An adenoma composed of dysplastic tubular crypts, as well as leaf- or finger-like structures, each contributing to more than 25%, but <75% of the adenoma.

Fortunately both tubulovillous or villous adenomas qualify as “advanced adenomas” for screening purposes, and the only “critical” cutoff is therefore is at least 25% of villous component. Needless to say, where 20% or 25% or 30% villous stops and starts is very much in the eye of the beholder.

Grading of Dysplasia Previously dysplasia in adenomas was graded as mild, moderate, and severe, with carcinoma in situ as a final category; however, now the WHO has resorted to the two tiered system of lowand high-grade dysplasia, which decreases inter- and intraobserver variability.

227 Indeed, now all management algorithms use this two-tiered system. In some countries, histologic grading has been taken altogether out of the management algorithms for adenomas, which may be a little premature given the tendency of some patients to produce small high-grade polyps and their possible predictive value for current or subsequently tumors elsewhere in the large bowel.

The criteria for grading dysplasia have been adapted from the National Polyp Study (USA), whereby high grade is differentiated from low grade by the presence of architectural complexity.

619 Back-to-back glands or cribriform appearance of the crypts represents complex architecture qualifying for high-grade dysplasia (

Fig. 20-39).

228 This is not without problems as many adenomas have a degree of budding representing increasing complexity in otherwise overtly low-grade polyps that is frequently ignored. In addition, adenomas commonly have foci with different degrees of dysplasia.

Adenomas likely go through a progression of dysplasia from low to high grade before becoming invasive, and the more severe the dysplasia, the more likely it is that a particular adenoma will contain a focus of invasive carcinoma.

197,

198,

229,

230,

231 This has been used as an argument for reporting degrees of dysplasia; however, it is well recognized that invasion can occur directly from low-grade dysplasia. It should also be noted that some adenomas simply acquire a higher-grade cytology without developing the architectural complexity required for calling it high-grade dysplasia, which is also reflected in the carcinomas that arise from it. Apart from submucosa mucin adenomas may rarely have ectopic bone (

Fig. 20-39F).

Reporting options include calling adenomas as having either low-grade or high-grade dysplasia. Some prefer to state whether there is or is not any evidence of high-grade dysplasia, omitting any reference to low-grade dysplasia. Although surprising, some physicians do not appreciate that all adenomas are, by definition, dysplastic, and, apparently, saying that a polyp is “dysplastic” irrespective of grade causes a panic reaction. On the other hand, since all adenomas need to be completely removed irrespective of the grade of dysplasia and all require surveillance colonoscopy, it may not matter as much. The exception is serrated polyps where stating that “there is no evidence of high grade dysplasia” does not distinguish SSP/As with and without low grade dysplasia, so requires a different reporting system for conventional adenomas and serrated polyps, which is also rather absurd.

Institutions vary in their approach on reporting grade of dysplasia in adenomas, whereby many do not routinely grade dysplasia or use it only when high grade is present. A good argument can also be made for using it in a biopsy of an obvious carcinoma endoscopically that shows only high-grade dysplasia, or when a biopsy is worrisome for a higher-grade lesion (invasive carcinoma), but an equivocal diagnosis cannot be made. Such lesions clearly require endoscopic or surgical resection, so a little excitement can be justified. The same argument is given for not mentioning “carcinoma in situ,” as some surgeons still believe this is an indication for colectomy in otherwise completely excised polyps. While we keep assuming it is only a matter of time before all such thinking retires, while it exists, pathologists need to be very aware of the thinking of the clinicians to whom these reports are sent, as ensuring no undue harm comes to the patient is one of our mandates.

Other Descriptive Terms Often Used for Adenomas Although for descriptive or study purposes the Paris classification is used, in practice there are several other terms also used, largely in clinical studies or for gross description of polyps. Although from a management point of view they are no different, a brief discussion is justified.

MICROSCOPIC ADENOMA. Sometimes dysplastic glands occur in otherwise unremarkable mucosa, to which the name microscopic (even unicrypt) adenoma has been applied. It is likely that most of these other than the very smallest would be identified by magnification endoscopy as “aberrant crypt foci.” These are particularly (but not always) found in unremarkable mucosa of patients with FAP, but likely all adenomas start this way. The only problem that they can cause is when encountered in random surveillance biopsies in IBD patients.

DIMINUTIVE ADENOMA. An adenoma up to 5 mm in diameter.

ADVANCED ADENOMA. This term is creeping into the clinical literature for polyps that are 1 cm or more in diameter, that have a villous component, or that have high-grade dysplasia. It is apparent that once adenomas are 1.0 cm in size that they are advanced and additional HGD or the presence of villi have no additional clinical significance. Not surprisingly, either “villousness” or HGD unless overt, are not very reproducible

amongst pathologists, and even less so in adenomas <1 cm, which is where it really matters as it puts the polyp into the “advanced” group. In the National Polyp Study, even 1-25% villous architecture resulted in an increased risk of subsequent adenoma formation of 2.7 over pure tubular adenomas of the same size. Similarly the risk for subsequent adenomas, using adenomas up to 5 mm as the control, was 3.3 for polyps 0.6-1.0 cm and 7.7 for those >1.0 cms

619. The good news was that in this study only about 1% of polyps ≤5 mm had HGD, a figure that increased to about 4.5% for polyps measuring 0.6-1.0 cm. It was also apparent that the proportion of polyps with HGD continued to increase with size, reaching about 25% for those over 2.0 cm.

FLAT AND DEPRESSED ADENOMAS (SYNONYMS NONPOLYPOID, PLATEAU, PLAQUE-LIKE, OR FLUSH-TYPE ADENOMAS). Flat adenomas are those whose thickness does not exceed twice that of the adjacent mucosa and macroscopically appear as small reddish, slightly raised, plaque-like spots, rarely more than 1 cm in diameter (

Fig. 20-40A). Some are the same thickness of the adjacent mucosa, while others are less thick than the adjacent mucosa, have a central depression, and are referred to as depressed adenomas (

Fig. 20-40B,C). Interestingly, whether flat or depressed, many of these lesions microscopically have an adjacent collarette of thickened mucosa. There is considerable controversy as to whether flat adenomas represent the early stage of formation of polypoid adenomas, as all adenomas have to start as small lesions, or whether they are different and have an increased risk of invasion. It is suggested that although small and endoscopically inconspicuous, flat adenomas frequently contain areas of high-grade dysplasia.

232,

233 It is speculated that these lesions might progress rapidly to small invasive carcinomas without any prior polypoid

growth phase and thus could represent a mechanism whereby CRCs apparently arise “de novo.”

234,

235

Reports from Japan indicate that they may form up to 6% of all adenomas found in patients undergoing meticulous colonoscopy in that country,

236 but anecdotal reports from experienced colonoscopists in the West

237 and a single autopsy study of 303 New Zealand Caucasian subjects

238 suggest a much lower prevalence. On the other hand, one retrospective study from Canada reported that 8.5% of all adenomas retrieved from pathology files were of flat type

239 and another prospective study from Omaha, Nebraska, found flat adenomas to have a similar prevalence to other adenomas but to occur in younger subjects

240: These differences are unexplained but clearly contribute to the uncertainty over the importance of flat adenomas in clinical practice.

The problem is that all adenomas must at some point be “flat,” so the term “flat adenoma” tends to be used for overtly sessile lesions satisfying these criteria, and better for those that are >5 mm in diameter, as this may be the group more likely to have HGD. The very low frequency of K-ras in flat adenomas suggests that they may be different; however, about 60% of polypoid adenomas are K-ras negative so that a transition cannot be excluded. Ideally a prospective natural history study is required in a series of flat adenomas, although the chances of that happening are remote.

Adenoma with Endocrine Cell Nests Occasionally small nests of endocrine cells similar to endocrine cell hyperplasia in autoimmune gastritis have been described in adenomas (

Fig. 20-41A,B).