Skin Grafts

David L. Brown

DEFINITION

A graft, unlike a flap, does not bring an independent blood supply with its tissue to the recipient site. Skin grafts can be defined based on their origin: autograft (same individual), allograft/homograft (another individual of the same species), or xenograft (from another species).

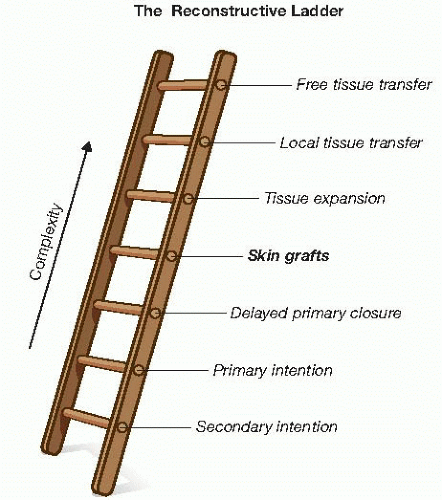

Skin grafts represent a rung on the proverbial reconstructive ladder above those of primary closure and healing by secondary intention and below local flaps (FIG 1).

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Skin grafting should only be considered once a viable recipient bed is obtained. This includes debridement of nonviable tissues, elimination of active infection, assurance of good vascularization to the wound bed, lack of significant fluid efflux from the wound (i.e., edema or bleeding), and coverage of vital structures (exposed bone, vessels, tendons, nerves, etc.).

Indications include inability to perform primary closure or insufficient tissues for local skin flap coverage, uncertainty of tumor clearance, and comorbid conditions.

Contraindications include active infection (i.e., bacterial counts >105 CFU/g via quantitative culture), poor vascularity of recipient bed (i.e., history of radiation to the area), and anticipation of further underlying reconstruction (i.e., nerve or tendon grafting).

FIG 1 • The reconstructive ladder. Skin grafts occupy an intermediate position in the heirarchy of complexity of closure technique.

Relative contraindications: comorbidities that can affect the healing of skin grafts such as diabetes, smoking, and venous insufficiency.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

Patients should be counseled regarding postoperative expectations, wound management, and restrictions so that they can make preparations prior to the operation.

Care of the donor site

Split-thickness grafts—Xeroform versus OpSite versus other coverings. May shower; more pain with Xeroform; watch for leaks and infection with OpSite

Full-thickness grafts—Steri-Strips. May shower; some bruising; minimal pain

Care of the graft site—bolster dressing. May shower if bolster is exposed, but do not let water run through the bolster continuous as this will wash out mineral oil (if used on cotton inside) and allow bolster to dry out over graft. Bolsters are usually taken down in 4 to 6 days, unless infection is suspected, then earlier.

Choice of graft thickness

Split-thickness skin grafts (STSGs)

12/1,000 inch is standard, with 6-16/1,000 inch being used for special situations.

Thinner grafts: more assured healing at the recipient site; the more dermis is left behind for subsequent harvest as necessary and the less primary contraction and greater secondary contraction.

Thicker grafts: more durable, as they carry more dermis with them.

“Sheet” (unmeshed) grafts have the advantage of better cosmesis but are encumbered by seroma or hematoma formation underneath, which can lead to local failure of the graft. These grafts should be inspected early at approximately 24 to 48 hours and any underlying fluid removed via aspiration. “Pie crusting” is unaesthetic and is not associated with higher graft survival.

Meshing of grafts can be performed with two advantages. One is coverage of greater recipient surface area with less donor graft. The ratios 1:2 or 1:1.5 are more commonly used, whereas 1:4 is typically reserved for extreme cases only. The larger the graft expansion, the more tenuous the coverage, and the more secondary contraction will occur. The second advantage is wound bed drainage and prevention of seroma or hematoma formation resulting in graft failure. A common method is meshing 1:1.5 but applying the graft to the recipient site in an unmeshed fashion.

Full-thickness skin grafts (FTSGs)

Primary contraction is greater (about 40%), but secondary contraction is less (about 15%), making them a good choice for joints, neck, eyelids, and so forth.

Donor sites from FTSGs (usually straight-line layered closures) have the benefits of little postoperative pain and minimal scarring compared to STSGs.

Choice of meshing versus sheet grafts

Meshing: allows for egress of wound fluids and lessens the risk of seroma and hematoma. As interstices must heal via secondary contraction and re-epithelialization, meshed grafts will contract more over time and be less durable. More wound area is able to be covered with less donor site.

Sheet grafts: prone to hematoma and seroma but are aesthetically more pleasing and exhibit less secondary contraction. Useful on hands and feet, across joints, and on the face and neck.

TECHNIQUES

SPLIT-THICKNESS SKIN GRAFTS

Patient Positioning and Setup

The patient is positioned either prone or supine, so that the lateral or anterolateral thigh is accessible for graft harvesting.

The approximate donor site is marked out from several inches below the trochanter to several inches above the knee (smaller if less is needed).

The donor site is injected with local anesthetic in the subdermal space, using a 22-gauge spinal needle. A mixture of 0.5% lidocaine with 1:200,000 concentration of epinephrine and 0.25% bupivacaine works nicely for providing both hemostasis and postoperative pain relief.

Mineral oil is spread over the area to allow for smooth gliding of the dermatome over the skin (FIG 2).

Preparing the Dermatome

The dermatome is assembled, and the appropriate width guard is attached (FIG 3A). A 3-in guard is appropriate for most applications and fits the contour of the thigh well in most adult patients.

Proper seating of the blade in the machine and underneath the guard is assured; uneven seating can cause an excessively thin graft at one edge and overly thick at the other.

The desired thickness of skin harvest is selected via the dial on the side (12/1,000 inch is shown here) (FIG 3B).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree