Simple Mastectomy

Michael S. Sabel

Lisa Newman

DEFINITION

A simple mastectomy, also commonly referred to as a total mastectomy, is the surgical removal of all breast tissue, including the nipple-areolar complex and enough overlying skin to allow closure. A simple mastectomy does not include removal of the axillary contents; when the breast tissue and axillary lymph nodes are removed en bloc, this is referred to as a modified radical mastectomy (MRM) (see Part 5, Chapter 12). Variations of the simple mastectomy, typically performed in concert with immediate reconstruction include the “skin-sparing mastectomy,” where the nipple-areolar complex is removed but the overlying skin is preserved; and the “nipple-areolar sparing mastectomy,” where the native skin and nipple-areolar complex are preserved. These are described in Part 5, Chapter 11.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

In clinically early-stage breast cancer, survival is largely driven by risk of distant organ micrometastatic disease and ability to control/eliminate this aspect of the cancer with adjuvant systemic therapy. Locoregional manifestations of disease in the breast and axilla can usually be controlled with surgery and radiation. Multiple prospective, randomized clinical trials have therefore documented survival equivalence between breast-conserving and mastectomy surgery for invasive breast cancer as well as for ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). Lumpectomy for a diagnosis of breast cancer is usually followed by breast radiation to sterilize microscopic/occult foci of disease in the remaining breast tissue, thereby reducing the incidence of ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence. Many women will nonetheless undergo total mastectomy as the primary breast surgical option either because of personal preference, medical contraindication to breast radiation, or because of disease features suggesting inability to achieve a margin-negative lumpectomy with a cosmetically acceptable result (e.g., diffuse suspicious-appearing microcalcifications on mammogram, multiple breast tumors not amenable to resection within a single lumpectomy, unfavorable tumorto-breast size ratio). It is important for the clinician to remember that aesthetic acceptability must be defined by the patient. Total mastectomy is also the conventionally accepted surgical approach for breast cancer prophylaxis in high-risk women such as those with hereditary susceptibility.

A detailed history and physical examination is imperative on the first consultation with these patients. In addition to the details of their breast cancer diagnosis, the history should cover medical comorbidities, medications, surgeries, allergies, and also any musculoskeletal issues, which could affect operative positioning and/or radiation treatment planning. Prior chest wall irradiation (such as for Hodgkin’s lymphoma or as part of breast-conserving treatment for a past ipsilateral breast cancer) is a contraindication to reirradiation and breast conservation for a new or recurrent breast cancer. Connective tissue disorders such as Sjögren’s syndrome or scleroderma can result in severe radiation-related toxicity and patients with these medical conditions will typically require mastectomy for management of breast cancer, even if the tumor is detected at a small size that would otherwise have been amenable to breast-conserving surgery. Patients that are unable to raise the arm above shoulder level may have difficulty tolerating the breast radiation tangents.

All breast cancer patients should have a detailed family cancer history, focusing on both the maternal and paternal sides of the family. Patients with a strong family history, particularly of breast and ovarian cancer, should receive genetic counseling. These patients may want to consider bilateral mastectomies for prevention of second cancers.

A bilateral breast and lymph node examination, including the axillary, cervical and supraclavicular lymph nodes, is critical. Any patient with clinically evident lymph nodes should undergo further evaluation, including axillary ultrasound and fine needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy.

Breast examination should focus on the size and location of the tumor, fixation to the underlying musculature or overlying skin, and skin changes, particularly those consistent with inflammatory breast cancer (erythema, swelling, peau d’orange) or locally advanced disease (bulky tumors, tumors with secondary inflammatory changes, or cancers associated with matted nodal disease). These patients may require neoadjuvant chemotherapy in order to downstage the cancer and to improve resectability. A coordinated multidisciplinary approach, including input from medical and radiation oncology specialists promptly following the breast cancer diagnosis, is important for efficient management planning and is vital to the successful treatment of these patients.

Early-stage breast cancer patients with a clinically negative axillary exam undergoing total mastectomy require axillary staging, which can usually be performed as lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy. Mastectomy patients with axillary metastases documented by either needle biopsy or SLN dissection require standard levels 1 and 2 axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) or MRM, and postmastectomy locoregional radiation needs are then determined by the full pathologic extent of disease identified in the breast and axillary contents.

All patients planning mastectomy should be presented the option of immediate reconstruction and a consultation with a plastic surgeon. Patients who opt for immediate reconstruction may be candidates for a skin-sparing or nipple-areolar sparing mastectomy. If postmastectomy radiation is being considered, this might impact the patient’s options and eligibility for immediate reconstruction. Because the axillary nodal status is a strong predictor of postmastectomy radiation benefit, it may therefore be helpful to perform the SLN biopsy prior to the mastectomy surgery in cases where immediate breast reconstruction is planned.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Breast imaging plays a vital role in the screening and diagnostic workup for breast cancer. Imaging can define the extent of the disease and help assess for any abnormalities in the contralateral breast. Bilateral mammography is essential for any patient with breast cancer. Any suspicious contralateral lesions should be worked up before making the final surgical decision.

Axillary ultrasound can be performed in many patients with a biopsy-proven invasive cancer to identify suspicious nodes suggestive of regional involvement. Suspicious nodes on axillary ultrasound should undergo an FNA biopsy with ultrasound guidance.

It should not be assumed that any axillary node that is palpable or suspicious on ultrasound is malignant, as often they may be reactive. They should always be interrogated with FNA biopsy; and if the FNA is negative, then definitive axillary staging should be performed by SLN biopsy. At the time of lymphatic mapping and sentinel node dissection, it is important to excise any palpable/suspicious node, regardless of whether or not the node has any appreciable radiocolloid or blue dye uptake. If local resources permit, intraoperative evaluation of the sentinel node(s) with frozen section analysis can also be useful so that the patient can proceed onto immediate completion of the ALND if metastatic nodal disease in confirmed. When frozen section analyses are available and planned, the patient must be consented preoperatively for possible conversion from total mastectomy to MRM.

The use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is controversial. For patients undergoing mastectomy, MRI may detect contralateral cancers that were not visualized on mammography. For patients that hope to pursue breast-conserving surgery, a preoperative breast MRI may detect suspicious foci of disease in the breast such that mastectomy may be recommended. MRI usage has therefore been associated with increased rates of bilateral mastectomies. However, MRIs are sensitive but not specific and may lead to false-positive findings that necessitate additional biopsies. Furthermore, the natural history of MRI-detected multifocal/multicentric lesions in the cancerous breast is unclear, as these areas of otherwise occult disease would typically be radiated following lumpectomy for the known cancer. Retrospective and prospective studies of outcome following breast-conserving surgery in patients whose breast-conserving surgery eligibility was planned with versus without breast MRI have failed to demonstrate any significant differences in cancer-related outcomes.1, 2, 3 We do not recommend routine MRI but rather its use should be on a patient by patient basis.

In the absence of locally advanced disease (skin or muscle involvement, multiple matted nodes), routine staging tests, such as computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis, or bone scan, are not indicated.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

In the preoperative area, the breast to be removed should be clearly marked and confirmed with the patient.

Prophylactic antibiotics have been shown to reduce postoperative infections and are indicated.4 Sequential compression devices should be placed prior to initiation of general anesthesia for venous thromboembolism (VTE) prevention.

Positioning

The patient should be positioned supine with the arm out laterally, taking care not to abduct the arm greater than 90 degrees as this may cause an injury to the brachial plexus. For a simple mastectomy, it is not necessary to prep and drape the ipsilateral arm into the field. However, if an SLN biopsy with frozen section and possible ALND is planned, it may be reasonable to include the arm using a sterile stockinette and Kerlix wrap. The endotracheal tube should be positioned toward the contralateral side of the mouth from the side of the mastectomy.

Position the table and lights to allow enough room above the arm for an assistant to stand.

If an SLN biopsy is to be performed and blue dye is to be injected, this can be done at this time. Either isosulfan blue dye or dilute methylene blue dye can be injected subareolar, periareolar, or peritumoral, according to surgeon preference.

The chest wall, axilla, and upper arm are prepped into the field. Be sure to prep widely, extending across the midline and onto the abdomen and neck.

TECHNIQUES

CHOICE OF INCISION

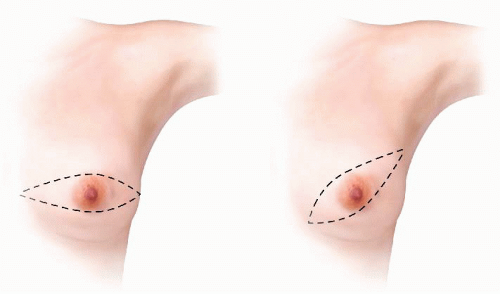

The standard incision for a simple mastectomy is the classic Stewart incision, an ellipse oriented medial to lateral, encompassing the nipple-areolar complex and any prior biopsy scar (FIG 1). Alternatively, the modified Stewart incision is angled toward the axilla. It has been suggested that the modified Stewart incision, by excising more of the dermal lymphatics running toward the axilla, may provide better local control.

In addition to the Stewart and modified Stewart, there are alternate options for a simple mastectomy. The placement and orientation of the incision must be based on the location of the biopsy scar and/or the location of the tumor. For a palpable tumor, particularly one close to the skin, the skin over the tumor should be included in the excised skin. Planning of the skin incision in conjunction with the plastic surgeon can be quite helpful in patients undergoing skin-sparing mastectomy and immediate reconstruction. If the patient has a surgical cancer biopsy incision, this scar should be resected with the underlying mastectomy specimen. Incisions located in proximity to the nipple-areolar complex can be resected within the central skin ellipse that is being sacrificed. Incisions that are located remote from the central nipple-areolar skin can sometimes be resected as a separate ellipse of sacrificed skin, as long as the remaining skin bridge is wide enough to remain viable. The original surgical cancer biopsy scars should not be left intact in the mastectomy skin flaps because of the oncologic concern that this skin

may potentially harbor cancer cells (and the mastectomy skin is usually not being radiated, as is the case following lumpectomy); and from a wound healing perspective, the subcutaneous fat deep to the traumatized incisional skin will be less healthy and more likely to necrose. Old surgical biopsy scars that are unrelated to the cancer diagnosis can be left in place. Also, percutaneous needle biopsy scars can be left intact on the skin flaps, as these have not been shown to contribute to risk of local recurrence.

It is important to remove enough skin so that there is no redundancy but not so much that there is undue tension on the incision. A useful method to determine the placement of the superior and inferior incisions is to hold a marking pen in the air over the nipple and retract the breast inferiorly. Mark this site on the skin and then retract the breast superiorly to mark the inferior extent (FIG 2A,B).

When designing the ellipse, closure will be facilitated by making sure the superior and inferior incisions are of equal length (FIG 3). This can easily be assessed using a 3-0 silk suture.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree