Scene Preparedness

Marc Eckstein

Ray Fowler

INTRODUCTION

Preparedness is the key to being able to respond safely and efficiently to terrorist incidents. Even though one certainly cannot plan for every possible contingency, certain fundamentals must be in place to maximize the effectiveness of the response and mitigation of this type of incident. This chapter discusses the key elements of scene preparedness that must be in place in order to minimize the resultant loss of life.

PREPAREDNESS ESSENTIALS

LOCAL CAPABILITY

The Emergency Medical Services (EMS) agency planning for terrorist events should know the capabilities of the local EMS system. In order to prepare for the potential “mass casualty” incident, the planner should have answers to these questions. How many EMS resources are available at any one time on a “normal” day? Of these resources, how many ambulances are available?

This local capability assessment is the first step in determining the overall needs of any particular system. If only a few ambulances are on the streets, how can scores of patients be transported from an event resulting from a terrorist incident? An example of such a capability assessment would be found in planning for a smallpox outbreak. The planner should, for example, identify a cadre of medical provider individuals who could serve in the role of “mass vaccinators,” in coordination with the public health department. Such a cadre can be screened for their “prevaccination” appropriateness through various methods, such as Internet-based services (See http://www.smallpoxscreen.us) (1). Additionally, the American Medical Association (AMA) Center for Disaster Preparedness and Emergency Response maintains a database of providers that are trained in smallpox immunization skills from their Advanced Disaster Life Support (ADLS) course (2). This database may be essential in the identification of a skilled workforce in the event of a smallpox outbreak.

MUTUAL AID

Most EMS provider agencies, especially smaller ones, typically have mutual aid agreements in place. These agreements serve to quickly augment the normal capacity of a system, both in terms of manpower and transport resources. Questions that the EMS agency preparing for a medical terrorism event must answer include: How many additional ambulances can be summoned? What is the estimated time to get these additional resources on-scene?

A mutual aid agreement usually stipulates that resources and personnel will only be provided if conditions permit (i.e., if the other agencies can spare some of their resources). Obviously, this will depend upon the scope and location(s) of the incident. For this reason, it is beneficial to have mutual aid agreements in place with multiple agencies. One important factor to consider in terms of the provision of mutual aid staffing and equipment is that all agencies typically account for their full-time and part-time personnel rosters. Full-time personnel commonly work part-time at other agencies and thus may be counted as a resource for a second agency (or more). Thus, personnel rosters may indeed show a larger number of personnel than are physically available to respond because an individual responder may be counted as a potential responder by more than one agency.

CALLBACK SYSTEM

Each system should have an internal system in place to augment its daily staffing with a callback/holdover system. In the event of a terrorist incident, which may generate a large number of patients, a system must be in place to recall off-duty personnel and augment resources with reserve apparatus. This callback system must be as automated as possible, with at least one backup method in place. Relying on off-duty personnel to call a single phone number for instructions is impractical

because of the overwhelming number of calls that come in to individual(s) answering the phone. Additionally, out-of-service (or crowded) land-lines make a backup method of contact essential.

because of the overwhelming number of calls that come in to individual(s) answering the phone. Additionally, out-of-service (or crowded) land-lines make a backup method of contact essential.

A functional callback system ensures the availability of additional personnel and activation of additional reserve equipment. Off-duty personnel must have specific, preauthorized standing orders that direct them where to go and to whom to report. The spontaneous response of numerous off-duty FDNY firefighters from their homes directly to the World Trade Center incident, for example, created a myriad of additional problems. “Chain of command and control” and accountability issues arose as additional manpower entered the “immediate danger to life and health” (IDLH) area without the knowledge of any supervisors. Also, responding individuals may have been placed at risk by not having the basic personal protective equipment (PPE) that the on-duty firefighters had.

INCIDENT COMMAND SYSTEM

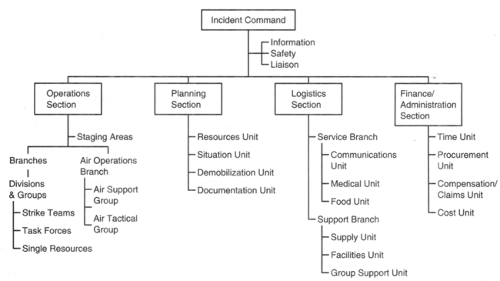

Strict adherence to the incident command system (ICS) is essential to respond to a terrorist incident optimally (Fig. 23-1). The only way to fully incorporate the ICS into a terrorist incident is to utilize ICS appropriately in the daily operations of the EMS agency. One of the advantages of the ICS is its flexibility and adaptability. Therefore, the ICS should be used whether an incident involving 2 patients or 200 patients is being handled.

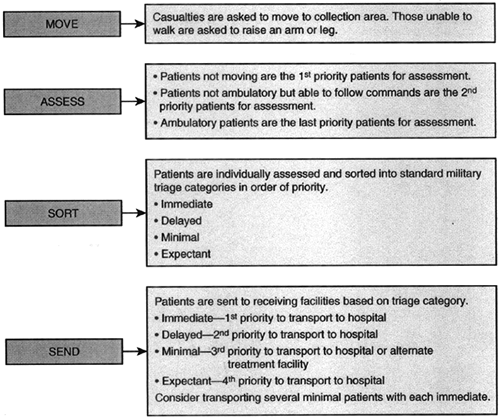

In establishing the ICS, it is imperative for the first-arriving resources to provide an accurate “size-up” of the scene. The estimated number of patients should be determined through standard triage sorting using a triage assessment system such as the MASS (Move-Assess-Sort-Send) triage method (Fig. 23-2) (2,3,4). This system, which utilizes standard military triage categories and is compatible with many civilian triage systems (such as START Simple Triage and Rapid Transport), allows first responders to rapidly identify the number of “Immediate,” “Delayed,” and “Minor” patients that must be managed, as well as the number of persons in the “Expectant” category that have been identified. By separating patients based on their ability to ambulate or move, patients are separated into categories based on the gross motor component of the Glasgow Coma Score (GCS). There is evidence that supports the gross motor component of the GCS as the most sensitive indicator of who will survive and who will not (2,3,4,5,6). One additional critical point is that triage is a dynamic process. Patients may change categories upon reassessment as patients initially identified in one group may improve or worsen. Additionally, Expectant patients should be upgraded to Immediate when resources become available to care for them.

Any identified or potential hazards must be delineated to allow incoming personnel to take the necessary precautions and don the appropriate PPE. This hazard assessment cannot be overemphasized enough. Secondary explosive events, such as the secondary bomb that was detonated at the Atlanta clinic bombing and the second plane crash into the World Trade Center, have shown that injury to emergency providers is of major concern. This risk is not just to the lives of the providers but also to the ultimate mitigation of the effects of the incident.

In addition to estimating the number of patients, a command post location and designation should be made. A location for the staging of incoming resources must be established. Instructions must be broadcast through appropriate channels regarding the safest approach to the incident. Important questions that must be immediately addressed include:

Is a parking area nearby for apparatus to stage?

Should the parking area be uphill from the event?

Is the wind direction pertinent so that resources should approach from an upwind direction?

Where will the responding agencies park, so that ingress and egress can be controlled carefully?

An individual must remain with each vehicle with the keys to the vehicle so that no responding unit blocks the egress of

another vehicle when patient transport—or potentially expanding hazard—requires the movement of the vehicle. Finally, the command post location should allow for an expanding incident and for the arrival of additional agency/ department representatives.

another vehicle when patient transport—or potentially expanding hazard—requires the movement of the vehicle. Finally, the command post location should allow for an expanding incident and for the arrival of additional agency/ department representatives.

Establishing a unified command is essential for any terrorist incident. “Managers” from each key agency involved in such an incident must be designated. Invariably a need will arise for representatives (“agency reps”) to be present from law enforcement, fire suppression, EMS, public health, federal agencies, and so on. The overall commander for the incident will depend on the type of incident. A multiple casualty shooting incident with the shooter still on-scene, for example, will typically have a law enforcement leader serve as the incident commander (IC), whereas a chemical weapons release would likely have a fire department officer serve as the IC.

SPECIALIZED RESOURCES

Larger EMS provider agencies, particularly those that are fire department-based, typically have the ready availability of a number of specialized resources. Some of these resources that may be needed for a terrorist incident include hazardous materials (hazmat) teams and equipment, decontamination (decon) teams and equipment, metropolitan medical response system (MMRS), Tactical Emergency Medical Support (TEMS), and so on. The greater the availability of these specialized resources on a regular basis, the faster they can respond to such an incident. This faster response will make it easier to integrate these teams into an operation. This is because the individuals comprising these teams will regularly train with the other firefighters and agencies and will become accustomed to working within the same chain of command. Logistical issues such as unfamiliarity with the ICS, different types of PPE, different radio frequencies, different medical protocols, and different standard operating procedures (SOPs) make the integration of some of these specialized teams very problematic at a real incident.

MEASURES OF SUCCESS

How can the successful mitigation of a terrorist incident be measured? Three benchmarks by which to measure success in this area are useful:

No responder became a victim during the event.

Potentially salvageable patients received care in a timely manner.

The time elapsed from the time of alarm of the incident until the time of transport of the last Immediate patient was kept to a minimum.

Item 1 is self-explanatory. How do first responders, whether they are firefighters, emergency medical technicians, or law enforcement officers, avoid becoming victims? With proper training and constant reinforcement,

first responders will maintain appropriate vigilance to suspect a terrorist incident every time they respond. This vigilance actually begins with properly trained dispatchers. If multiple calls are received by the dispatch center for “persons down,” especially in an enclosed location (or a “high risk” location), it is incumbent upon the dispatch center to notify the first responders that multiple calls on this incident for multiple victims have been received, especially if callers are describing a particular constellation of signs and symptoms (such as one of the “toxidromes”). Such prompting by the dispatcher should advise the use of caution by the first responder and may result in a larger dispatch of multiple resources, including the closest hazmat squad to perform air sampling. This warning should prompt the first responders to consider donning the appropriate level of PPE as they approach the incident location.

first responders will maintain appropriate vigilance to suspect a terrorist incident every time they respond. This vigilance actually begins with properly trained dispatchers. If multiple calls are received by the dispatch center for “persons down,” especially in an enclosed location (or a “high risk” location), it is incumbent upon the dispatch center to notify the first responders that multiple calls on this incident for multiple victims have been received, especially if callers are describing a particular constellation of signs and symptoms (such as one of the “toxidromes”). Such prompting by the dispatcher should advise the use of caution by the first responder and may result in a larger dispatch of multiple resources, including the closest hazmat squad to perform air sampling. This warning should prompt the first responders to consider donning the appropriate level of PPE as they approach the incident location.

The role of the call-taking and dispatch agency in community preparedness for terrorist events bears careful examination. Indeed, this agency is often the first contact of professionally organized resources with the event (though on-scene professional personnel, such as public safety individuals, may already be present). Thus, those preparing the community for potential terrorist events must be especially skilled in such areas as the interpretation of events that may have multiple victims. An example would be in setting to high priority those calls coming to the agency in which multiple victims have altered levels of consciousness and/or are experiencing various other emergency conditions, such as seizures. This would quickly give concern to the agency that a potential toxic exposure is ongoing, and thus appropriate warning would be quickly conveyed to responding agencies. Many agencies are utilizing computer-based syndromic surveillance for just this purpose: to identify conditions and situations in which multiple victims of various conditions must be identified (shortness of breath, for example), and to help prepare responding agencies for potential hazards (7).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree