Restorative Proctocolectomy: Hand-Assisted Laparoscopic Surgery Ileal Pouch-Anal Anastomosis

Robert R. Cima

DEFINITION

An ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (IPAA) is a restorative procedure used when the entire colon and rectum needs to be removed and the patient wishes to avoid a permanent ileostomy. The two most common indications for IPAA are chronic ulcerative colitis (CUC) and familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) syndrome. Although the procedure is basically the same, the frequency and indications for surgery are different, and for the purposes of this chapter, the focus will be on the surgical treatment of CUC.1

IPAA involves removal of the entire colon and rectum followed by construction of an ileal reservoir most commonly in a “J shape” that is anastomosed to the anal canal by either a stapled or hand-sewn technique.

This maintains the normal route of defecation, although the frequency and consistency of the stool is different than normal bowel function.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Primarily, CUC needs to be distinguished from Crohn’s colitis. This is particularly important, because a restorative IPAA is not recommended in Crohn’s disease patients.

Other acute colitis syndromes (i.e., toxic bacterial colitis, cytomegalovirus [CMV] colitis, ischemic colitis) can mimic CUC. Thus, a thorough workup to differentiate between CUC and other disease processes needs to be considered prior to surgery.

A detailed review of the patient’s disease course including past endoscopic findings, prior imaging studies, and any history of perianal disease needs to be evaluated. Any history of small bowel inflammation or perianal abscesses, fistulas, or fissures is highly suggestive of underlying Crohn’s disease.

FIG 1 • CT enterography (coronal view, venous phase). Severely inflammed distal colon in a CUC patient with normal appearing small bowel.

In patients with an established history of CUC presenting with an acute worsening of their symptoms, it is important to rule out an infectious cause such as Clostridium difficile or CMV colitis as the cause of their disease exacerbation.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

CUC is characterized by recurrent episodes of bloody diarrhea associated with urgency and tenesmus.

Approximately 15% of patients will present initially with fulminant disease, characterized by high-volume bloody diarrhea, severe abdominal distension and pain, fever, and systemic signs of illness. In severe situations, the patient might have peritonitis as the result of colonic perforation or hemodynamic compromise from volume depletion and systemic inflammation.

More commonly, the CUC patient with medically refractory disease will not have any characteristic physical findings. However, prolonged disease activity can be associated with poor overall nutritional status and significant weight loss.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Computed tomography (CT) enterography is the most commonly used imaging study in CUC patients (FIG 1). The use of intravenous (IV) contrast is essential to highlight intestinal inflammation and helps identify any evidence of small bowel inflammation, which is highly suggestive of Crohn’s disease.

In active CUC, the CT will demonstrate inflammatory changes around the involved colon with thickening of the colonic wall. This inflammation usually starts in the rectum and extends proximally into the colon for a varying distance.

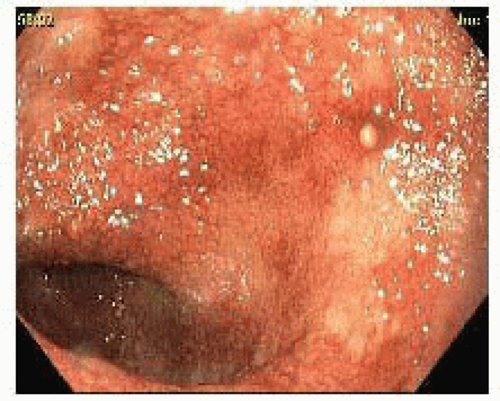

Endoscopic imaging of the colon is essential (FIG 2). It should demonstrate continuous inflammation from the rectum for a variable distance, extending proximally into the colon. Evidence of discontinuous mucosal inflammation is worrisome for an underlying diagnosis of Crohn’s disease.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Frequently, an IPAA for the treatment of CUC is performed in stages, depending on the patient’s overall health at the time of surgery or the indications for surgery.

The primary indications for surgery are toxic or fulminant disease activity, medically refractory disease, and/or evidence of dysplasia/malignancy.

In an emergency situation, or in an ill patient on multiple immunosuppressive medications, the first operation is a subtotal colectomy with an end ileostomy.

Once the patient recovers his or her health, a completion proctectomy with IPAA and diverting ileostomy may be performed. At the last operation (the third stage), the ileostomy is reversed.

In outpatients with mild disease that are coming to surgery, the total proctocolectomy with IPAA and diverting loop ileostomy may be performed at a single operation.

In some institutions, the diverting loop ileostomy may be routinely omitted, depending on a number of patient- and procedure-specific factors. However, the majority of centers recommend use of a temporary diversion.

TECHNIQUES

PATIENT PREPARATION PRIOR TO SURGERY

After a detailed discussion regarding the risks, alternatives, benefits, and expected outcomes from the IPAA, the patient should see a certified wound, ostomy, and continence nurse (WOCN) for preoperative education and appropriate site marking for a temporary diverting loop ileostomy. Many patients are provided with a mechanical bowel preparation with oral antibiotics. This is an optional step as there is mixed data as to the necessity of such preparation. An alternative approach would be to perform a tap water enema the morning of surgery to clear the distal colon and rectum. All patients are provided with antimicrobial soap (Hibiclens™) to shower with the night prior to surgery and the morning of surgery.

PATIENT INDUCTION AND POSITIONING

Prior to the induction of anesthesia, the patient is given 5,000 units of heparin subcutaneously and sequential compression devices are placed on the lower extremities. The patient is positioned supine on the operating table lying on an upper body gel pad to minimize movement during operating room (OR) position changes. Once induction of anesthesia is complete, an orogastric tube is placed. An indwelling urinary catheter is placed using sterile technique.

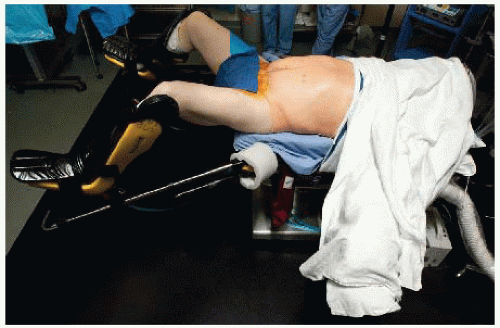

Once all necessary IV access is secured, the patient is repositioned in a modified lithotomy position (FIG 3). The heels are firmly planted on the stirrups to avoid pressure along the calves and the lateral peroneal nerves. The thighs are placed parallel to the ground to avoid conflict with the surgeon’s arms and instruments during the procedure.

Both arms are wrapped in gel pads and the patient’s right arm is placed next to his or her side and secured in position by positioning of an acrylic toboggan. The left arm is placed on an arm board positioned straight outward (FIG 3). Alternatively, both arms may be placed at the patient’s side, but this will impede access to the arms during the procedure in case the anesthesia team needs to intervene. A chest strap is applied to minimize the risk of the patient shifting on the operating table during frequent position changes during the procedure. A forced warm air warming device is placed on the chest and over the left arm is positioned outward.

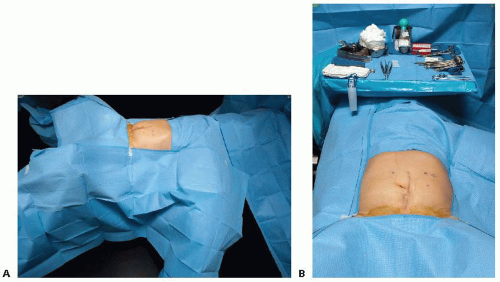

The abdominal wall skin is prepared with a chlorhexidine-alcohol mixture after the perineum has been scrubbed and painted with a Betadine-iodine skin preparation kit. The patient is then draped in a fashion that allows access to the entire abdomen and perineum (FIG 4A).

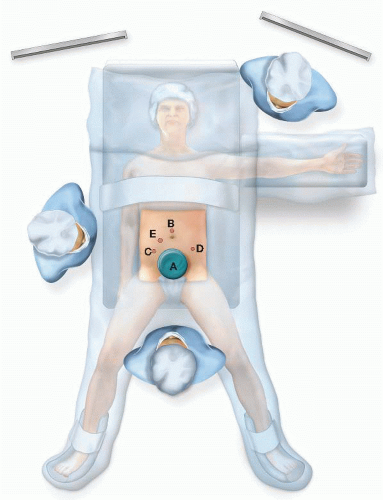

Video monitors should be placed directly off of the patient’s left and right shoulders. If a monitor is available on a boom and it can be positioned over the patient’s head which facilitates the dissection in the midportion of the patient’s upper abdomen. The scrub nurse should have his or her instruments positioned over the patient’s chest and head and he or she should stand on the patient’s left side above the outward-positioned left arm (FIG 4B). The surgeon will stand between the patient’s legs for the hand-assisted laparoscopic mobilization and resection of the abdominal colon. The first assistant/camera operator will initially stand on the patient’s right side (FIG 5).

Prior to incision, Surgical Care Improvement Project (SCIP)-compliant antibiotics are administered and documented. A procedural pause is performed, confirming the patient identity, procedure, position, antibiotic administration, allergies, and special equipment needs.

INCISION AND TROCAR PLACEMENT

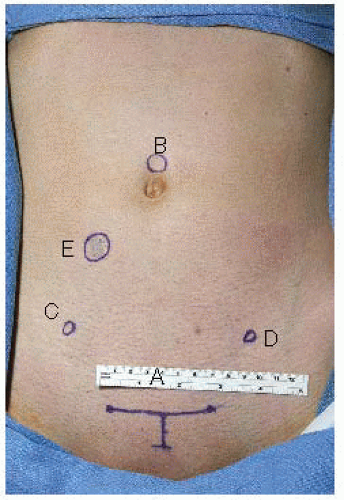

A midline incision is marked on the patient’s abdomen from the pubis to the xiphoid process in case emergent entry into the abdomen is required. In men, our preferred incision for the hand port is a 7-cm lower midline incision starting 1.5 cm above the pubic bone. In women, we prefer a 7-cm Pfannenstiel incision centered on the midline 1.5 cm above the pubis. If a prior midline or Pfannenstiel incision exists, we will use that incision.2,3

The hand-port incision is made and the abdomen is entered under direct vision. With the surgeon’s hand in the abdomen through the primary incision, a small 5-mm incision is made in the upper aspect of the umbilicus and a nonbladed 5-mm trocar is guided into the abdomen with the surgeon’s hand protecting the abdomen content form inadvertent injury. Next, the hand access device is placed in the lower abdominal incision and pneumoperitoneum is established.

Under laparoscopic visualization, a 5-mm nonbladed trocar is placed in the left lower abdomen and another in the right lower abdomen. Usually, the best location is 2 to 2.5 cm medial and 1 cm inferior to the superior iliac crest (FIG 6).

MOBILIZATION OF THE LEFT COLON

The patient is placed in steep Trendelenburg position with left side up. The surgeon stands between the legs and the camera operator is on the patient’s right side. A 5-mm camera is placed through the supraumbilical trocar. The surgeon places his or her left arm through the hand-port device and uses the left lower quadrant trocar for his or her dissecting scissors (FIG 7). The surgeon uses his or her hand to push the small bowel into the right lower quadrant and to lift the omentum into the upper abdomen. The left colon is then grasped and pulled medially and anteriorly. The camera is used to look over the surgeon’s hand into the left abdomen.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree