Resection of Head and Neck Melanoma

Scott A. McLean

DEFINITION

Resection of head and neck cutaneous melanoma is performed with wide surgical margins intended to achieve histologically negative margins. Current guidelines for wide excision of the primary lesion, with an adequate margin of surrounding normal skin and deep soft tissue necessary to achieve clear surgical margins, are based on depth of invasion of the primary lesion (Table 1).1 However, given the complex anatomic and functional nature of the head and neck, resection margins are sometimes modified to preserve normal function. Reconstruction of complex head and neck defects is often delayed until final histopathologic evaluation of margins is deemed negative. Reconstruction can be accomplished with primary closure, split- or full-thickness skin grafts, local or regional adjacent tissue transfer, or free tissue transfer.

Patients with invasive melanoma and no clinical evidence or regional metastatic disease may warrant assessment of regional lymph nodes via sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy. SLN biopsy has been shown to be both accurate and prognostic in head and neck melanoma.2,3 Current recommendations on use of SLN biopsy are based on depth of invasion of the primary lesion as well as the presence of adverse histologic features such as ulceration and mitotic rate. Patients with melanoma measuring 1 mm or greater should be offered SLN biopsy. SLN biopsy should also be considered in patients with a thickness of between 0.76 and 0.99 mm if they have any of the following adverse features: greater than or equal to 1 mitotic figure per square millimeter, lymphovascular invasion, satellitosis, or young patient age. SLN biopsy may also be considered with thin melanoma when the deep margin was broadly transected.1, 2, 3, 4, 5

Patients who present with clinical evidence of regional metastatic disease and patients who are found to have micrometastatic disease on sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) are offered completion lymph node dissection (CLND). Based on the site of the primary lesion, the nodal basins included in the CLND may include the postauricular and suboccipital lymph nodes, the parotid gland and its associated lymph nodes, and the cervical lymph nodes levels I to V (Table 2) (see Part 5, Chapter 31).6

Table 1: Surgical Margin Recommendations for Cutaneous Melanoma | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

Table 2: Nodal Basins Included in Therapeutic Lymph Node Dissection | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Cutaneous melanoma of the head and neck usually presents as a pigmented lesion of varying size, shape, and color. Other benign and malignant cutaneous lesions can present in a similar fashion and include the following:

Seborrheic keratosis

Junctional nevi

Compound nevi

Dermal nevi

Hemangioma

Blue nevus

Pyogenic granuloma

Spitz nevus

Pigmented actinic keratosis

Pigmented or nonpigmented basal cell carcinoma

Squamous cell carcinoma

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

A thorough history of the lesion of concern should include the duration of clinical symptoms; the presence of pruritus; bleeding; and any changes in the size, shape, or color of the lesion.

Most cutaneous melanomas will present as either a new pigmented lesion or changes in an existing lesion that exhibit the ABCDs of melanoma: A-Asymmetry, B-Border, C-Color, D-Difference (a change in the lesion).

A thorough past medical history should be performed and include information regarding any previous malignancies, past surgical procedures, current medications and allergies, family history of cancer, problems with anesthesia, and social history—including smoking history, occupation, sun exposure, and history of blistering sunburns.

A focused review of systems should also be completed and include review of any constitutional, musculoskeletal, neurologic, respiratory, gastrointestinal, hepatic, skin, and lymphatic signs or symptoms.

All newly diagnosed melanoma patients should undergo full body skin evaluation.

A complete head and neck exam should be performed on every patient and include a thorough skin exam and palpation of the suboccipital, postauricular, parotid, and cervical nodal basins to rule out the presence of clinically palpable regional metastatic disease.

A detailed cranial nerve exam should be performed to document preoperative cranial nerve function.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Newly diagnosed patients with localized cutaneous melanoma are not recommended to undergo distant metastatic workup. In the absence of clinical signs or symptoms of distant metastatic disease, no imaging modality has been shown to be useful in detecting occult metastatic disease and in fact more often lead to false-positive findings, requiring further unnecessary invasive procedures.1

Chest x-ray and serum lactate dehydrogenase are also both insensitive for the detection of occult metastatic disease.

Many patients will require preoperative chest x-ray, complete blood count (CBC), and electrocardiogram (EKG), depending on age, health status, and need for general anesthesia.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

Prior to proceeding to the operating room, the primary cutaneous lesion should be reexamined and confirmed with the patient. The surrounding skin should also be reexamined to make sure no new lesions have developed. In addition, the plan regarding surgical margins and primary closure versus delayed reconstruction should be confirmed with the patient. All cranial nerve functions in the operative field should also be retested prior to surgery.

Patients who are scheduled for SLN biopsy in conjunction with excision of their primary cutaneous lesion will undergo lymphoscintigraphy prior to their definitive excision.

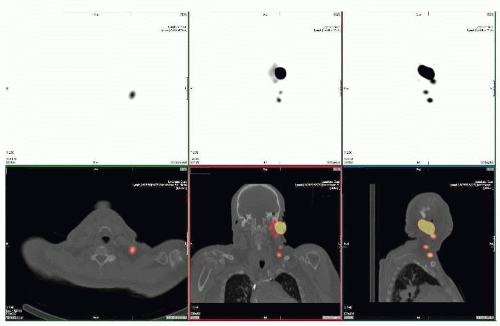

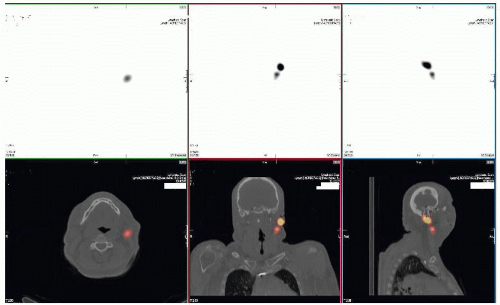

This procedure is done in the nuclear medicine department and is enhanced by the use of single-photon emission computed tomography-computed tomography (SPECT-CT) imaging.7 Prior to proceeding to the operating room, the SPECT-CT/lymphoscintigraphy should be reviewed to determine the likely location of the SLN(s) (FIGS 1 and 2). These locations should then be discussed with the patient and marked appropriately. If the location of a likely SLN is in close proximity to a cranial nerve, this should be discussed with the patient and the cranial nerve function should be well documented.

Appropriate use of antibiotics and deep vein thrombosis (DVT) prophylaxis should also be discussed prior to proceeding to the operating room.

In addition, it is crucial to have a thorough discussion with the anesthesia team regarding the use of long-acting paralytics. If cranial nerves are likely to be in the operative field, as is almost always the case in the resection of head and neck melanoma, the anesthesia team must be aware to avoid the use of long-acting paralytics.

Positioning

Patients who are scheduled for wide local excision alone (melanoma in situ or T1a lesions) often can tolerate surgery under sedation with monitored anesthesia. In these cases, the head of the bed is often rotated 90 degrees away from the anesthesia cart to allow for easy access to the surgical field. Oxygen delivery methods can be designed to avoid

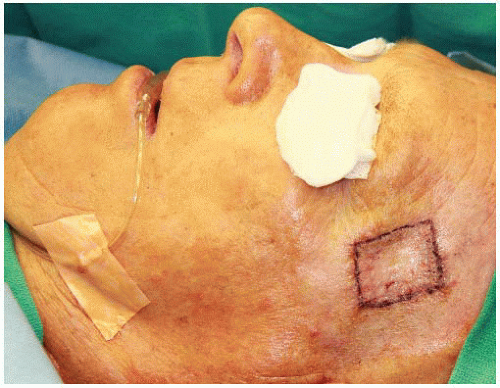

crossing the surgical field and may include either nasal cannula or mask. In these cases with free-flowing oxygen, it is very important to discuss the risk of fire with the entire operating room team. The entire face and neck can be prepped into the operative field. Wide draping can then be used with attention to avoid any tenting of drapes, which could lead to pooling of oxygen in the operative field (FIG 3).

Patients who are scheduled to undergo SLN biopsy in conjunction with the primary excision are almost always placed under general anesthesia. Again, the use of long-acting paralytics must be avoided. The head of the bed can be rotated 180 degrees away from the anesthesia cart to allow for easy surgical access to the operative field. Most primary lesions can be excised with the patient in the supine position. Rarely, the patient may need to be turned prone to allow access to the posterior scalp or suboccipital nodal basin. With the patient intubated, either half of the face and neck or the entire face and neck can be prepped and draped, depending on the need for surgical access.

TECHNIQUES

PLACEMENT OF PLANNED INCISIONS

Primary Lesion Excision Site

The primary lesion is carefully inspected and cleaned with a moist sponge. The lesion should be marked out with careful attention to include any evidence of dermal extension. This may include any pale, erythematous, or lightly pigmented extension from the primary lesion (FIG 4).

With the primary lesion now marked, the appropriate margin is then marked circumferentially around the visible lesion. The excision margin is most often 1 to 2 cm, depending on the depth of invasion of the primary lesion.

In certain functional situations, the excision margin may be left a little short of standard margins. For example, if a lower eyelid lesion requires 2-cm margins, but at 1 cm the excision would cross the lid margin, it may be acceptable to use 1 cm (FIG 5). In this case, the surgeon must be willing to reexcise this margin should it return positive on final histopathologic review.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree