Repair of Ventral and Umbilical Hernias

Most ventral hernias occur through previous laparotomy incisions. Small defects may be closed by reopening the incision, clearing the fascia, and then closing as one would close a laparotomy incision. Frequently, multiple defects are present; thus, it is important to explore the entire incision. If closure cannot be accomplished without excessive tension, synthetic mesh may be used to bridge the gap. This chapter illustrates one method of primary closure by separation of parts. This is commonly used as a delayed method of closure after damage control laparotomy, when the fascia has retracted and is difficult to approximate.

Steps in Procedure

Make incision over hernia and extending beyond it in both directions (usually through old scar)

Try to stay in retroperitoneal plane to avoid damage to adherent bowel

Raise flaps in all directions and define defect—there may be multiple defects

Choose method of repair—avoiding use of prosthetic material if possible

Repair by separation of parts:

Widely develop flaps in plane between subcutaneous fat and fascia

Create relaxing incisions in lateral aspect of anterior rectus sheath as needed

Close fascia in midline

Place closed suction drains under flaps

Repair by use of prosthetic mesh

Suture mesh to fascial edges, either as a patch or as an extension of the fascia

Close fascia as needed

Place closed suction drains under flaps if necessary

Umbilical hernia repair

Make incision in umbilical crease if possible

Identify and reduce sac

Close fascia transversely using a vest-over-pants approach

Tack underside of umbilicus to fascia to recreate normal appearance

Hallmark Anatomic Complications

Injury to bowel during dissection

Recurrence due to excessive tension during closure or to unidentified secondary defects

Two methods of incisional hernia repair using prosthetic mesh are also detailed in this chapter. In addition, a variety of repair techniques using autogenous tissue are described and referenced at the end. The wide variety of techniques available attests to difficulties with recurrence after the most meticulous repair.

Laparoscopic ventral hernia repair (Chapter 44) is an increasingly popular alternative to open herniorrhaphy in selected patients.

Umbilical hernias are a special category of ventral hernias. Repair can usually be accomplished by a primary fascial overlap (see Figs. 43.4 43.5 and 43.6).

Ventral Hernia Repair

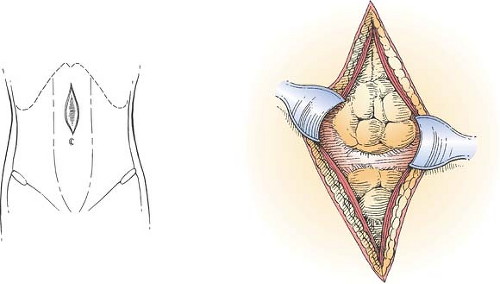

Exposure of Fascia and Definition of Defect (Fig. 43.1)

Technical and Anatomic Points

Excise the old scar and deepen the incision cautiously until you encounter the hernia sac. Often, the sac lies quite close to the skin surface. It may be adherent to the old scar. It will look somewhat like a large lipoma and, as with a lipoma, is easily “shelled out” of the surrounding tissues. Dissect laterally around the sac and then deep to expose good fascia well past the edge of the defect. Define the defect on all sides, raising

flaps of subcutaneous tissue and skin as the dissection progresses. In most cases, the entire length of the old incision should be exposed because multiple defects are quite common and may otherwise be overlooked. Lateral defects, which frequently occur at points where retention sutures have cut through the fascia or at old drain sites, must be sought as well. Expose good fascia on all sides of the old incision. If possible, dissect the sac away from the fascia and reduce it. You will then be able to perform the repair in a totally extraperitoneal fashion. It is critical to clean the underside of the fascia carefully so that gut is not caught in a stitch during the repair.

flaps of subcutaneous tissue and skin as the dissection progresses. In most cases, the entire length of the old incision should be exposed because multiple defects are quite common and may otherwise be overlooked. Lateral defects, which frequently occur at points where retention sutures have cut through the fascia or at old drain sites, must be sought as well. Expose good fascia on all sides of the old incision. If possible, dissect the sac away from the fascia and reduce it. You will then be able to perform the repair in a totally extraperitoneal fashion. It is critical to clean the underside of the fascia carefully so that gut is not caught in a stitch during the repair.

Generally, multiple adjacent defects should be made into one defect by excising intervening bridges of attenuated fascia. Débride all attenuated fascia, hernia sac, or scar tissue.

If the defect is small, close it with interrupted nonabsorbable sutures. Be careful to avoid excess tension. If tension is required to appose the fascial edges, the repair will fail. Remember that it is difficult to assess the tension on the repair under the conditions of muscle relaxation associated with general or spinal anesthesia. Therefore, if there is any tension, consider performing separation of parts or using prosthetic material to bridge the gap (see subsequent sections and references at the end).

Separation of Parts (Fig. 43.2)

Technical and Anatomic Points

Develop flaps in the avascular plane where the subcutaneous fat is loosely adherent to the fascia (Fig 43.2A). These flaps should extend out to the flanks to minimize tension. Occasional perforating vessels may be encountered—ligate these and divide them as necessary.

Test the closure for tension. Remember that any tension that is evident with the patient under anesthesia (with muscle relaxation) will be accentuated when the patient is awake. If the

closure is still tight, relaxing incisions can be made in the lateral aspect of the anterior rectus sheath as shown in Fig. 43.2B). This generally provides sufficient laxity to close without tension.

closure is still tight, relaxing incisions can be made in the lateral aspect of the anterior rectus sheath as shown in Fig. 43.2B). This generally provides sufficient laxity to close without tension.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree