Repair of Inguinal and Femoral Hernias

The muscular and aponeurotic layers of the abdominal wall form a strong continuous barrier that supports and contains the intraabdominal viscera. This continuous barrier is breached in the groin by the inguinal canal, an oblique passage from the abdomen to the scrotum (in the male) or to the labium majus (in the female). This anatomically complex area is a frequent site of hernia formation.

Steps in Procedure

Inguinal Hernia Repair

Skin crease incision

Incise aponeurosis of external oblique muscle from external ring laterally

Identify and preserve ilioinguinal nerve

Mobilize spermatic cord (or round ligament, in females)

Incise cremaster muscle fibers to expose spermatic cord fully

Seek indirect sac

If one is found, separate sac from cord structures, twist, and suture ligate (resecting redundant sac)

In female, divide and ligate round ligament with sac

Assess floor of canal and choose method of repair

Bassini Repair

Place Allis clamps on conjoined tendon and pull down

Create relaxing incision on fascia

Suture conjoined tendon to inguinal ligament with multiple interrupted sutures

In male, internal ring should admit Kelly clamp; in female, close internal ring completely

McVay Repair

Place Allis clamps on conjoined tendon and create relaxing incision as above

Clean Cooper’s ligament of overlying fatty and fibrous tissue

Suture conjoined tendon to Cooper’s ligament with multiple interrupted sutures

In vicinity of femoral vein, transition to inguinal ligament

Shouldice Repair

Incise transversalis fascia in direction of its fibers

Reflect superior leaf of transversalis fascia and clean underside, identify arch of aponeurosis of transversus abdominus muscle

Running monofilament suture from pubic tubercle toward internal ring; suture arch of aponeurosis to iliopubic tract

At internal ring, run suture line back toward pubic tubercle, suturing free edge of superior leaf to inguinal ligament and tie suture to itself

Begin third suture line at internal ring; suture conjoined tendon to inguinal ligament; at pubic tubercle, return suture line back to internal ring and tie suture to itself

Plug-and-Patch Repair

Define edges of any defect in transversalis fascia

Place preformed plug into the defect and tack it in place

Overly the patch over the floor of the canal, bringing the tails around the spermatic cord

Suture the patch in place

Closure of Canal after Repair

Check hemostasis and close external oblique aponeurosis with running suture (taking care to avoid iliohypogastric nerve)

Close fascia and skin

Femoral hernia repair

Repair from Below

Incision directly over femoral hernia, parallel to inguinal ligament

Isolate sac and open it

Reduce any contents (check for viability)

If necessary, incise inguinal ligament vertically to enlarge canal

Twist, suture ligate, and amputate the sac

Create a rolled “cigarette” of permanent mesh and insert it into the canal, suture in place

Suture inguinal ligament back together if necessary

Close subcutaneous tissues and skin

Repair from Above

Widely expose floor of inguinal canal as for inguinal hernia repair

Open floor of canal to expose femoral region

Identify sac as diverticulum of peritoneum extending down into leg

Open the sac and reduce the contents

Perform McVay repair as outlined above

Hallmark Anatomic Complications

Missed hernia

Injury to ilioinguinal nerve

Injury to iliohypogastric nerve

Injury to genitofemoral nerve

Testicular edema or ischemia

Injury to femoral vein

Postherniorrhaphy pain

List of Structures

Inguinal region

Processus vaginalis

External (Superficial) Inguinal Ring

Medial and lateral crus

Intercrural fibers

Internal (deep) inguinal ring

Hesselbach’s triangle

Inferior Epigastric Artery and Vein

Pubic branch of artery (accessory obturator artery)

Obturator artery

Superficial (Camper’s and Scarpa’s) fascia

Innominate fascia

External oblique muscle and aponeurosis

Internal oblique muscle and aponeurosis

Transversus abdominis muscle

Transversalis Fascia

Iliopubic tract

Transversalis fascial sling

Preperitoneal tissue

Peritoneum

Pubic tubercle

Inguinal ligament

Pectineal (Cooper’s) ligament

Lacunar ligament

Conjoined tendon

Interfoveolar ligament

Ilioinguinal nerve

Iliohypogastric nerve

Genitofemoral Nerve

Genital branch

Femoral canal

Femoral sheath

Femoral Artery and Vein

Greater saphenous vein

Saphenous hiatus

Fascia lata

Male

Spermatic cord

External spermatic fascia

Cremasteric muscle and fascia

Internal spermatic fascia

Vas deferens

Scrotum

Testis

Testicular vessels

Female

Round ligament

Labium majus

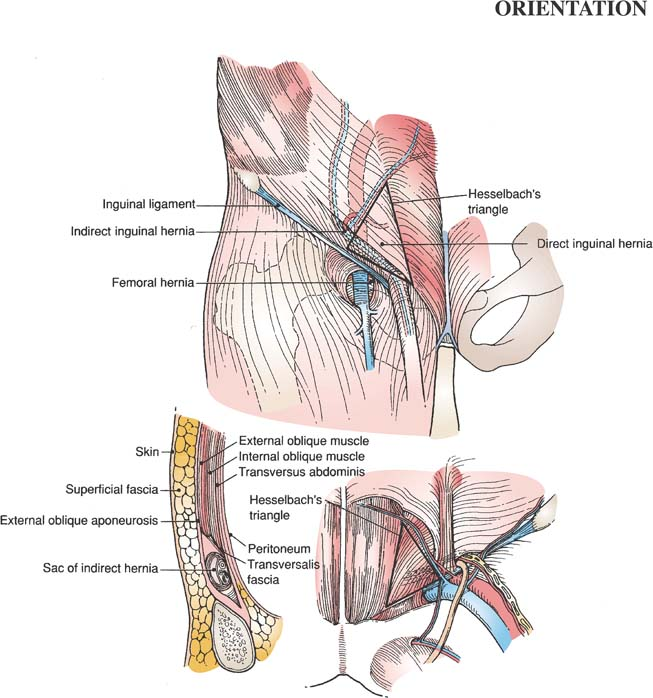

Three types of groin hernias are distinguishable clinically: indirect inguinal, direct inguinal, and femoral. An individual may have one, two, or (occasionally) all three hernias within the same groin.

Indirect inguinal hernia is the most common hernia in both males and females. In the male, indirect inguinal hernia is associated with persistent patency of the processus vaginalis. Communicating hydroceles are closely related. The spermatic cord traverses the abdominal wall as it passes from the internal to the external ring to supply the testis. This produces an area of natural weakness in the male. In the female, the round ligament exits the abdomen to anchor in the labia majora and mons pubis. Indirect hernias in females form in much the same way as do those seen in males.

Direct hernias are generally acquired as a result of weakness in the floor of the inguinal canal that allows intraabdominal pressure to produce a bulge through the thinned-out transversalis fascia. Indirect hernias occur lateral to the inferior epigastric vessels, whereas direct hernias project straight through the floor of the canal in the region of Hesselbach’s triangle, medial to the inferior epigastric vessels.

The femoral canal is inferior to the inguinal ligament. A femoral hernia occurs when weakness in the femoral canal allows herniation of peritoneum, followed by intraabdominal

viscera, into the canal. Femoral hernias are seen most commonly in elderly patients. Small, incarcerated femoral hernias may feel exactly like enlarged lymph nodes. The combination of small bowel obstruction and palpable adenopathy in one groin should lead one to suspect an incarcerated femoral hernia.

viscera, into the canal. Femoral hernias are seen most commonly in elderly patients. Small, incarcerated femoral hernias may feel exactly like enlarged lymph nodes. The combination of small bowel obstruction and palpable adenopathy in one groin should lead one to suspect an incarcerated femoral hernia.

|

In this chapter, four types of inguinal hernia repair—the Bassini, McVay, Shouldice, and plug-and-patch methods—are described. Femoral hernia repair from both below and above is described. References at the end of the chapter give details of other techniques, and laparoscopic herniorrhaphy is described in Chapter 95.

Descriptions of the anatomy of the inguinal region are confusing, in part because the standard texts of anatomy are based on dissection of the embalmed cadaver (in which tissue planes are not nearly as definable as in fresh tissues) and in part because of the plethora of synonyms applied to structures in this region. Here, the terminology commonly used by surgeons is presented. (Because of the inherent complexity, a long orientation section is given here.)

The abdominal wall is multilayered. These layers can be classified as either superficial or deep, and they are mirror images of each other, with the reflecting plane being the internal oblique muscle. Thus, from superficial to deep, the following layers are encountered:

Skin

Superficial (Camper’s and Scarpa’s) fascia

“Outer” investing (innominate) fascia

External oblique muscle and aponeurosis

Internal oblique muscle and aponeurosis (Note: in the inguinal canal, the spermatic cord or round ligament of the uterus substitutes for this layer.)

Transversus abdominis muscle and aponeurosis

“Inner” investing or endoabdominal (transversalis) fascia

Preperitoneal tissue

Peritoneum

The inguinal canal is a triangular passageway through the body wall in which lies the spermatic cord or its female homolog, the round ligament of the uterus. Its entrance is the internal inguinal ring, which is associated with the transversalis fascia and which is located immediately superior to the middle of the inguinal ligament and lateral to the inferior epigastric vessels. Its exit is the external inguinal ring, which is associated with the external oblique muscle and innominate fascia and which is located immediately superior to the medial end of the inguinal ligament at the pubic tubercle. Its anterior wall is the external oblique aponeurosis, its posterior wall is the transversus abdominis aponeurosis fused with transversalis fascia, and its base is the inguinal ligament.

The inguinal ligament is the somewhat thickened and in-rolled free edge of the external oblique aponeurosis that forms the inferior “shelving edge” of the inguinal canal. Laterally, it is attached to the anterosuperior iliac spine and the adjacent iliac fascia. Medially, it attaches to the pubic tubercle and adjacent pectineal ligament (of Cooper). The parallel fibers of the inguinal ligament that fan out to attach to the pubic tubercle and adjacent pectineal ligament form the lacunar ligament. It should be noted that the free edge of the lacunar ligament does not extend far enough laterally to participate in the formation of the normal femoral canal. The lacunar ligament does, however, lie inferior to (and thus supports) the spermatic cord in the medial part of the inguinal canal.

Immediately superior and lateral to the pubic tubercle, the aponeurotic fibers of the external oblique muscle diverge to attach to the body of the pubis superomedially (medial crus) and to the pubic tubercle inferolaterally (lateral crus). The triangular interval between the two crura, through which the spermatic cord or round ligament of the uterus passes, is the superficial or external inguinal ring. Intercrural fibers, which are derived from innominate fascia, are oriented at right angles to the external oblique fibers, convert the triangular hiatus into an oval, and usually prevent spreading of the crura. External spermatic fascia, the outer covering of the spermatic cord, is also derived from innominate fascia.

When fibers of the external oblique aponeurosis are split superolaterally from the superficial inguinal ring, the inguinal canal is opened. The somewhat transversely oriented muscular fibers of the internal oblique muscle can then be seen arching over the spermatic cord. The cremasteric muscle and fascia, which constitute the middle covering of the spermatic cord, are in continuity with the internal oblique muscle and its investing fascia. Internal oblique fibers in this region originate from iliac fascia, pass superficial to the spermatic cord and deep (internal) inguinal ring, and attach to the rectus sheath and adjacent body of the pubis. Rarely (3% of cases), the lowest internal oblique fibers are aponeurotic, join aponeurotic fibers of the transversus abdominis muscle, and insert into the pubic tubercle and pectineal ligament (of Cooper) as a conjoint tendon. However, typically, the lowest fibers are muscular and do not extend below the arch formed by the deeper transversus abdominis muscle. Because the internal oblique is primarily muscular in the inguinal region, it is of little importance in the surgical repair of groin hernias.

The third musculoaponeurotic layer is composed of the transversus abdominis muscle and aponeurosis and its investing fascia, the inner layer of which is transversalis fascia. By itself, transversalis fascia, which is intimately attached to the transversus abdominis muscle, has little intrinsic strength. Thus, it is considered with the muscle layer rather than as a separate, distinct entity.

Lower muscular or aponeurotic fibers of the transversus abdominis form a distinct arch extending from their lateral attachment (iliac fascia) to their medial attachment on the superior pubic ramus, lateral to the rectus abdominis muscle. As transversus abdominis fibers arch over spermatic cord structures laterally, they define the superior margin of the deep inguinal ring. Medial to the deep inguinal ring, the distinct arch is the superior limit of most direct inguinal hernia defects. Inferior to this arch, aponeurotic fibers of the transversus abdominis are present but are significantly reduced in number; these fibers diverge from each other, and the transversalis fascia fills the intervening gaps. It is this area—the posterior wall of the inguinal canal—through which a direct hernia occurs. Still more inferiorly, a collection of aponeurotic transversus and transversalis fascia fibers form the important iliopubic tract. Laterally, iliopubic tract fibers attach to the iliac fascia. From this attachment, which is overlapped by the inguinal ligament, fibers pass medially and deeply, diverging from the inguinal ligament. Fibers of the iliopubic tract define the lower border of the deep inguinal ring, cross the external iliac and femoral vessels and femoral canal as the anterior wall of the femoral sheath, and then fan out to attach to the pectineal ligament (of Cooper). Medial to the femoral canal, some fibers recurve inferolaterally, forming the medial wall of the femoral sheath. Thus, it is the iliopubic tract, not the more superficial and medial lacunar ligament, that forms the medial border of the femoral canal. Further, it should be noted that the iliopubic tract is often confused with the inguinal ligament because it more or less parallels the course of this ligament.

Although the transversus abdominis and transversalis fascia are considered as a unit, some attention must be paid to regional expressions that are unique to transversalis fascia only. One of these regional expressions is the transversalis fascial sling and its reinforcement by the interfoveolar ligament, which together form the medial boundary of the deep inguinal ring. The transversalis fascial sling results from the obliquity of the inguinal canal with respect to the plane of the deep inguinal ring. Abdominopelvic structures destined to become spermatic cord structures are located in preperitoneal tissue. When these

evaginate the transversalis fascia covering the deep inguinal ring (creating the internal spermatic fascia) to enter the inguinal canal, the axis of this tubular prolongation creates a redundancy of transversalis fascia at the medial side of the deep inguinal ring. This sling, which is intimately attached to the transversus abdominis muscle, is mobile and probably represents the so-called shutter mechanism thought to operate at the deep inguinal ring when lateral abdominal muscles contract.

evaginate the transversalis fascia covering the deep inguinal ring (creating the internal spermatic fascia) to enter the inguinal canal, the axis of this tubular prolongation creates a redundancy of transversalis fascia at the medial side of the deep inguinal ring. This sling, which is intimately attached to the transversus abdominis muscle, is mobile and probably represents the so-called shutter mechanism thought to operate at the deep inguinal ring when lateral abdominal muscles contract.

Remember that, during the embryologic descent of the testes, the first structure to pass out of the deep inguinal ring into the inguinal canal, and finally out of the superficial ring into the incipient scrotum, is the processus vaginalis, a tubular evagination of the peritoneal sac. Failure of fusion and subsequent fibrosis of this evagination provide a route for indirect hernias.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree