Rare Primary Thyroid Nonepithelial Tumors and Tumor-Like Conditions

Lester D.R. Thompson

PRIMARY ANGIOSARCOMA

Primary thyroid gland angiosarcoma is a malignant tumor of endothelial cell differentiation. This generally rare thyroid tumor is more common in the Alpine countries of central Europe where there is iodine deficiency.1 Although a pseudoangiomatous pattern can be seen in undifferentiated carcinoma, angiosarcoma is a distinct clinical, histologic, and immunophenotypic entity.

Etiology

Although the cause of thyroid angiosarcoma is considered to be multifactorial, its incidence is higher in countries where there is a dietary iodine deficiency—particularly the Alpine countries of central Europe.2,3 Interestingly, iodized salt prophylaxis in the mountain areas of Austria where there was previously iodine deficiency resulted in a decrease in the prevalence of angiosarcoma from 3% of all thyroid gland cancers4 in 1957-1975 to 0.7% in 1986-1995. Even so, these tumors are also reported in many countries where the intake of dietary iodine is adequate.1,5,6,7,8 Significant occupational exposure to industrial vinyl chloride and other polymeric materials may also be contributory.3

Histogenesis and Molecular Genetics

Clinical Presentation

Thyroid angiosarcomas account for <2% of all thyroid gland malignancies, although there is geographic variability, as discussed above. Women are affected much more frequently than men (4:1). Most cases arise in the seventh decade of life. Patients present with a painless mass that has often developed in the setting of long-standing goiter; other symptoms include dyspnea, asthenia, and weight loss.2,5,7,8,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17 Occasionally, a rapidly growing mass is noted with pressure symptoms.1,6,11,12 Hyperthyroidism is rare, with some authors suggesting that the angiosarcoma has a trophic effect on the follicular epithelium.18 Scintigraphic studies usually show a “cold” nodule,2 although ultrasound and CT studies can also be used to evaluate the nodule, showing a vascular tumor with irregular Doppler flow.12

Pathology

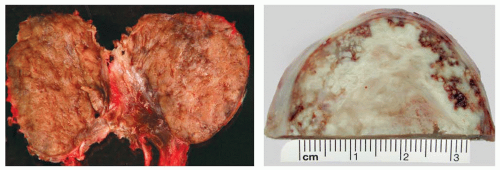

Gross Presentation

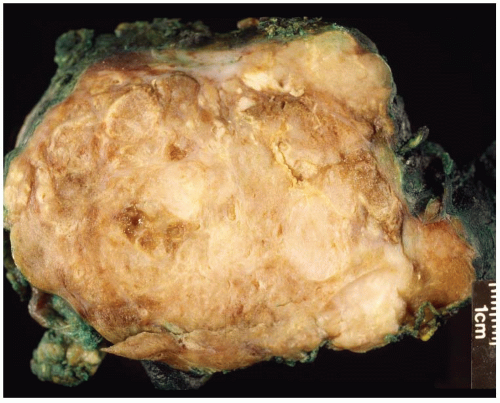

Macroscopically, the tumors may appear circumscribed, although in many cases it presents as an ill-defined mass infiltrating the thyroid parenchyma (Fig. 16.1). Tumors are usually large, measuring up to 10 cm. The cut surface is variegated, extensively hemorrhagic, with solid and cystic areas. Necrosis is common and extensive. Invasion of the surrounding soft tissues may be grossly identifiable.1,2,7,8,13,19

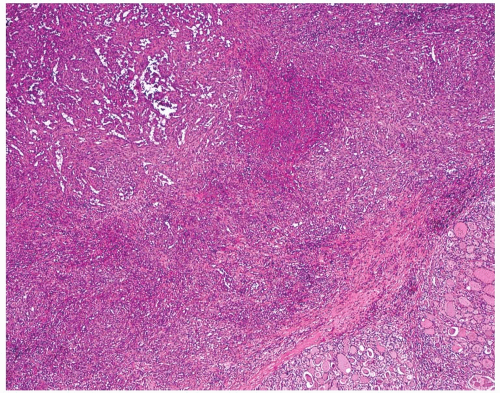

Microscopic Description

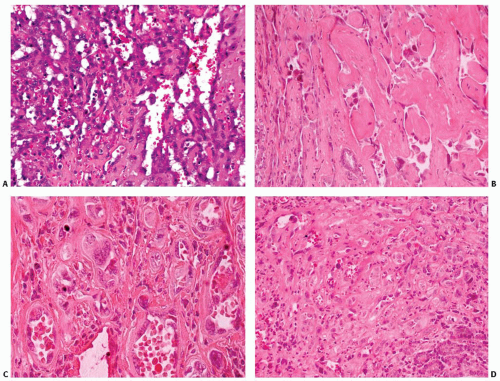

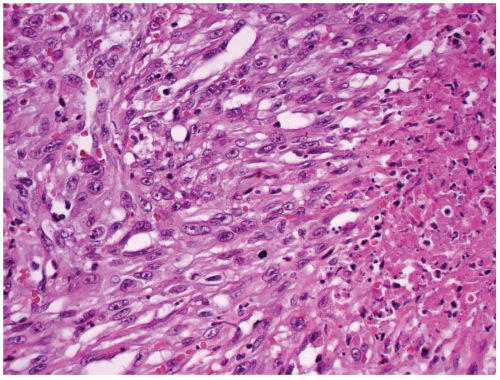

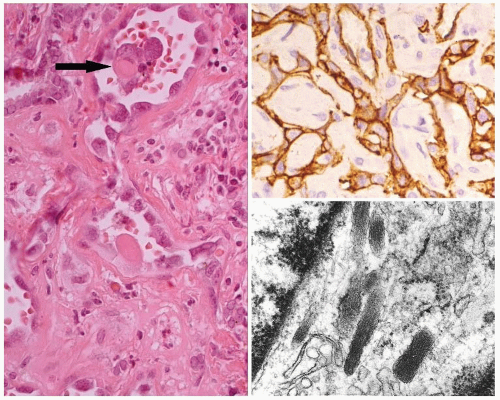

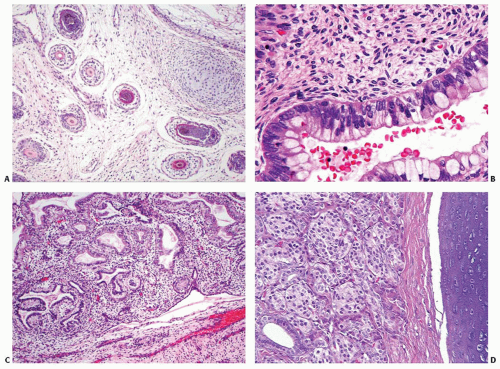

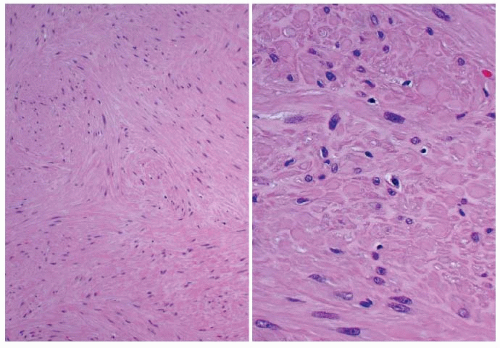

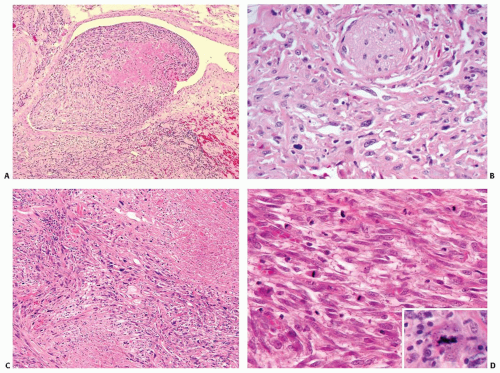

The periphery of the tumor is irregular. Freely anastomosing vascular channels infiltrate the adjacent parenchyma and soft tissues (Fig. 16.2). Tumor necrosis and hemorrhage are seen throughout. Various patterns can be seen, from solid, spindled, and papillary to pseudoglandular. Irregular, cleft-like to patulous, gaping vascular channels are common (Fig. 16.3A,B). The neoplastic large cells that line the vascular channels or are present in the solid areas are epithelioid (Fig. 16.3C,D). The cells have abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm surrounding round nuclei with vesicular nuclear chromatin (Fig. 16.4). The nuclei contain prominent, basophilic nucleoli, occasionally attached to the nuclear membrane by chromatin strands.1,5,8,11,13,20 The cells simulate undifferentiated carcinoma.2,5,20 Neolumen formation with erythrocytes within the newly formed channels is occasionally noted, although sometimes just vacuoles within the solid nests are present (Fig. 16.5).7,8,13,19 Mitotic figures, including atypical forms, are frequent. Multinucleated tumor giant cells are rare, although binucleated forms are occasionally present. Hemosiderin-laden macrophages are common. Single membrane-bound, rod-shaped cytoplasmic structures (Weibel-Palade bodies) can be identified only by electron microscopy (Fig. 16.5); a pericellular basal lamina, tight junctions, and subplasmalemmal pinocytotic vesicles are also noted.7,8,10,13,14,21

Immunohistochemistry and Molecular Diagnostics

The neoplastic cells are strongly and diffusely immunoreactive with vimentin and various vascular endothelial markers, including factor VIII-related antigen (FVIII-RA), CD34, CD31, and Ulex europaeus I lectin.1,2,5,6,7,8,10,11,12,13,14,17,20,22 It is important to identify cytoplasmic immunoreactivity and not just diffusion artifact or nonspecific uptake from the surrounding serum or from phagocytosis by cells in contact with the blood elements.23 The FVIII-RA staining is quite granular and seen in all tumor cells, not just in the luminal cells. Keratins are variably positive, ranging from a few isolated cells to diffuse immunoreactive of all tumor cells (Fig. 16.5). The variability of immunoreactivity may depend on the specific keratin used (AE1/AE3, CAM5.2, or CK7), although AE1/AE3 seems to be the most frequently positive.2,6,22 Thyroglobulin and thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF1) are negative. Smooth muscle actin and type IV collagen react around the endothelial cells, the former highlighting smooth muscle.1,2,6,7,8,13,19,20,22,24 TP53 nuclear immunoreactivity is rarely seen.8

Cytopathology

The interpretation of smears from a thyroid angiosarcoma is difficult, as the background is composed of necrotic material and

blood.11,15,25 Isolated large, neoplastic “epithelioid” cells are identified. They usually contain abundant eosinophilic to vacuolated cytoplasm with central, round nuclei that contain prominent nucleoli. Clusters of oval to round neoplastic cells are also noted. Cell borders are indistinct.6 Occasional intracytoplasmic lumina or vacuoles may be seen.11 It is important to not misinterpret these findings as a metastatic tumor or as an undifferentiated carcinoma.

blood.11,15,25 Isolated large, neoplastic “epithelioid” cells are identified. They usually contain abundant eosinophilic to vacuolated cytoplasm with central, round nuclei that contain prominent nucleoli. Clusters of oval to round neoplastic cells are also noted. Cell borders are indistinct.6 Occasional intracytoplasmic lumina or vacuoles may be seen.11 It is important to not misinterpret these findings as a metastatic tumor or as an undifferentiated carcinoma.

Differential Diagnosis

An angiomatous pattern can be seen in undifferentiated carcinoma,2,9,15,21,23,26 but there is often a greater degree of pleomorphism and significantly more giant tumor cells. Immunostains for endothelial markers confirm the diagnosis. Adenomatoid nodules with degenerative or retrogressive changes may contain areas of vascular proliferation. Organization of clot within a nodule can yield a mass lesion.15 In the post-fine-needle aspiration (FNA) setting, a Masson papillary endothelial hyperplasia type of reaction may be seen; sometimes, it is quite florid. However, a well-defined area of involvement, a finding of involvement within a vessel or nodule, a lack of cytologic atypia, and a lack of freely anastomosing vessels help make the distinction.15,27 Metastatic tumors (renal cell carcinoma and angiosarcoma25) and direct invasion into the thyroid gland from a soft-tissue primary should be separable based on clinical, radiographic, and histologic findings and immunophenotypic studies.28

Treatment and Prognosis

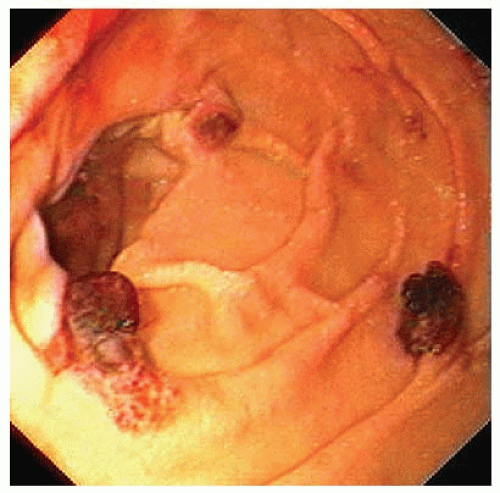

Combination adjuvant therapy (particularly rapid radiation) and surgical eradication may not alter the prognosis, as most patients

die of their tumors in <6 months, frequently from massive hemorrhage.2,3,5,7,11,12,14,18,20 Razoxane may benefit patients as a radiation sensitizer.3,8,16 In rare cases, a patient will survive beyond 5 years. Tumors confined to the thyroid gland seem to behave less aggressively than do tumors that spread extrathyroidally.3,7,8,16 Distant metastases (lung, gastrointestinal tract [Fig. 16.6], and bone) may cause fatal bleeding.1,2,3,20,24,28,29 Fibrinogen, factor VIII, and FVIII-RA in the serum may be used as surrogate markers during follow-up.16

die of their tumors in <6 months, frequently from massive hemorrhage.2,3,5,7,11,12,14,18,20 Razoxane may benefit patients as a radiation sensitizer.3,8,16 In rare cases, a patient will survive beyond 5 years. Tumors confined to the thyroid gland seem to behave less aggressively than do tumors that spread extrathyroidally.3,7,8,16 Distant metastases (lung, gastrointestinal tract [Fig. 16.6], and bone) may cause fatal bleeding.1,2,3,20,24,28,29 Fibrinogen, factor VIII, and FVIII-RA in the serum may be used as surrogate markers during follow-up.16

TERATOMA

Tumors of the cervical region are regarded as thyroid teratomas if (1) the tumor occupies a portion of the thyroid gland, (2) there is direct continuity or a close anatomic relationship between the tumor and the thyroid gland, and/or (3) a cervical teratoma is accompanied by a complete absence of the thyroid gland.30,31 The latter circumstance has been explained by two postulates: (1) total replacement of the gland by the tumor or (2) a thyroid anlage that failed to develop into a mature thyroid gland. In a given case, it may be difficult to rule out the possibility that the thyroid tissue found adjacent to a teratoma represents either normal thyroid gland secondarily replaced by a primary teratoma or just another component of the teratoma.30 Histologically, by definition, teratoma displays mature or immature tissues from all three embryonic germ cell layers: ectoderm, endoderm, and mesoderm.30,32 The interrelationship of these constituents and the percentage of each element that is present are used to classify the tumors into one of three types: mature, immature, or malignant. The terms teratoma, choristoma, hamartoma, heterotopia, epignathus, and dermoid are sometimes used interchangeably, but teratoma should be used only to describe a tumor with trilineage differentiation.

Histogenesis and Molecular Genetics

Teratomas include tissues from all three primordial layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm). They are believed to arise from misplaced embryonic germ cells (rests) in the thyroid gland that continue to develop in the new location.30

Clinical Presentation

Teratomas represent <0.1% of all primary thyroid gland neoplasms. The age range of affected patients at the initial presentation extends from newborns to 85 years, but the average age is <10 years. This average is skewed by the number of older patients

with malignant teratomas; the median age at presentation is <1 month.30,31,33,34,35,36,37 When neonates and infants are considered apart from children and adults, two distinct biologic groups appear: >90% of the tumors in the neonatal group are benign and >50% of tumors in the older group are malignant. There is no predilection for either sex.30 All patients present with a neck mass that often reaches a significant size. In addition, patients experience dyspnea, difficulty breathing, and/or stridor. Other congenital anomalies may be present in neonatal patients. Ultrasonographic images (in utero, at the time of birth, or later) provide the best information and are easiest to obtain. The most common finding is a multicystic mass lesion of the thyroid gland. CT demonstrates an inhomogeneous mass arising in the thyroid gland and compressing the upper airway for both benign and malignant teratomas (Fig. 16.7).30,38,39,40,41,42

with malignant teratomas; the median age at presentation is <1 month.30,31,33,34,35,36,37 When neonates and infants are considered apart from children and adults, two distinct biologic groups appear: >90% of the tumors in the neonatal group are benign and >50% of tumors in the older group are malignant. There is no predilection for either sex.30 All patients present with a neck mass that often reaches a significant size. In addition, patients experience dyspnea, difficulty breathing, and/or stridor. Other congenital anomalies may be present in neonatal patients. Ultrasonographic images (in utero, at the time of birth, or later) provide the best information and are easiest to obtain. The most common finding is a multicystic mass lesion of the thyroid gland. CT demonstrates an inhomogeneous mass arising in the thyroid gland and compressing the upper airway for both benign and malignant teratomas (Fig. 16.7).30,38,39,40,41,42

Pathology

Gross Presentation

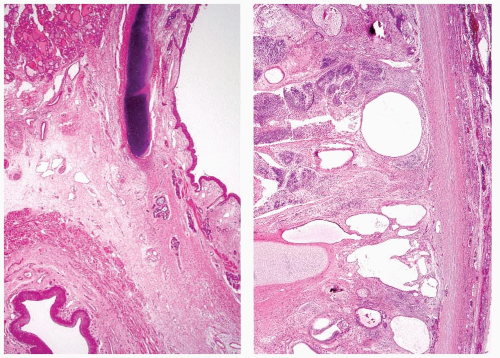

Teratomas range in size up to 13 cm in their greatest dimension (mean size 6 cm). Tumors associated with compression symptoms (stridor, hoarseness, and difficulty breathing) are on average larger than those not associated with these symptoms.30,31,33,34,36,37 The outer tumor surface varies from smooth to bosselated or lobulated. The tumor periphery is well circumscribed to widely infiltrative into the surrounding thyroid parenchyma. The tumor is firm to soft and cystic, the cut surface is multiloculated, and the cystic spaces contain white-tan creamy material, mucoid glairy material, or dark brown hemorrhagic fluid admixed with necrotic debris (Fig. 16.8). Material resembling brain tissue along with gritty bone or cartilage is frequently noted during gross examination.30,31,33,34,36,37

Microscopic Description

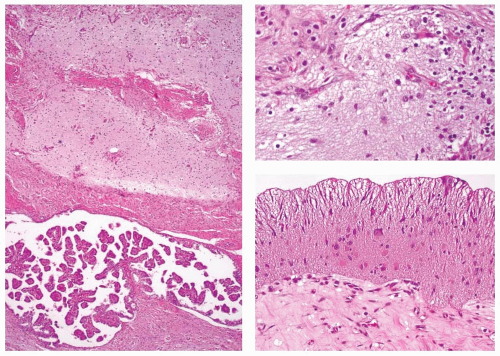

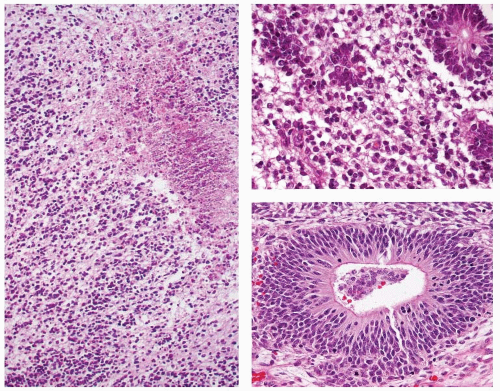

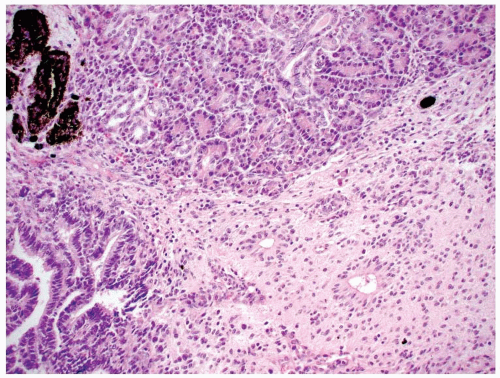

In order for a tumor to qualify as a thyroid teratoma, thyroid parenchyma should be identified somewhere within the mass (Fig. 16.9); even so, residual thyroid follicles are frequently scarce or absent in malignant teratomas. Teratomas display a wide array of tissue types and growth patterns within a single lesion (Fig. 16.10). Small cystic spaces to solid nests contain various different epithelia: squamous epithelium (simple and stratified), pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium (respiratory), cuboidal epithelium (with and without goblet cells) glandular epithelium (Fig. 16.11), and transitional epithelium. Pilosebaceous and other adnexal structures are seen (Fig. 16.11). True organ differentiation (pancreas, liver, or lung) can be found. Neural tissue (ectodermal derivation) is the most common element; it is composed variously of mature glial tissue (Figs. 16.10 and 16.12), choroid plexus, pigmented retinal anlage (Fig. 16.13), and/or immature neuroblastemal elements. The latter are composed of small-to-medium-sized cells with a high nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio, arranged in sheets or rosette-like structures (Homer Wright or Flexner-Wintersteiner types; Fig. 16.13). The nuclear chromatin is hyperchromatic. There are frequent mitoses. The maturation of the neural-type tissue determines the grade: completely mature (grade 0), predominantly mature (grade 1 or 2), and exclusively immature (grade 3 or malignant). Cartilage, bone, striated skeletal muscle, smooth muscle, adipose tissue, and loose myxoid to fibrous embryonic mesenchymal connective tissue are intermixed with the other components.30,38,39,40,41,43,44,45,46

FIGURE 16.7. Teratoma. A CT scan demonstrates a large multicystic neoplasm in the anterior neck, completely replacing the thyroid gland. *marks the laryngeal lumen. |

The grading criteria for gonadal and sacrococcygeal teratomas47,48,49 have been modified for thyroid teratomas. Benign, immature, and malignant teratomas are classified as such on the basis of the relative proportions of immature neuroectodermal tissues (see Table 16.1). Benign mature teratomas are classified as grade 0; benign immature teratomas are classified as grade 1 or 2; and malignant teratomas are classified as grade 3.30 The presence of embryonal carcinoma or yolk sac tumor would place a teratoma into the malignant category (grade 3).

Immunohistochemistry and Molecular Diagnostics

Malignant teratomas may require immunohistochemical evaluation. The immature glial components are immunoreactive with S100

protein, glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) (Fig. 16.14), neuron-specific enolase, and neural filament protein. Early skeletal muscle differentiation can be highlighted with myo-D1, myogenin (Fig. 16.14) or myoglobulin.30,36,39,46 Immature areas produce an increased proliferation fraction (MIB-1) that is often >10% in malignant cases.

protein, glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) (Fig. 16.14), neuron-specific enolase, and neural filament protein. Early skeletal muscle differentiation can be highlighted with myo-D1, myogenin (Fig. 16.14) or myoglobulin.30,36,39,46 Immature areas produce an increased proliferation fraction (MIB-1) that is often >10% in malignant cases.

Cytopathology

Smears from an FNA sample demonstrate various cellular components that are often misinterpreted as contamination or a missed lesion (i.e., the tumor was not sampled). The smears from malignant teratomas have a neuroepithelial small, round, blue cell appearance when taken from the immature neural elements. These cells result in a positive or malignant interpretation, rather than the pathologist making a specific diagnosis of malignant teratoma.30,38,39,41,50

Differential Diagnosis

The clinical differential diagnosis, especially in neonates, includes lymphangioma, thyroglossal duct cyst, and branchial cleft cyst.

Histologically, teratomas should be separated from dermoids (which only contain skin elements), extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, small-cell carcinoma, lymphoma, and melanoma.51 The diagnosis of teratoma under these circumstances is largely dependent on the identification of other tissue elements and a confirmatory immunohistochemical panel.30,31,41,45,51

Histologically, teratomas should be separated from dermoids (which only contain skin elements), extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, small-cell carcinoma, lymphoma, and melanoma.51 The diagnosis of teratoma under these circumstances is largely dependent on the identification of other tissue elements and a confirmatory immunohistochemical panel.30,31,41,45,51

FIGURE 16.10. Teratoma. Mature glial tissue, pigmented retinal anlage, salivary gland, and glandular epithelium are haphazardly arranged in benign mature teratoma. |

Treatment and Prognosis

The outcome for patients with thyroid teratomas depends on the patient’s age, the size of the tumor at the time of presentation, and the presence and proportion of immaturity. The age at presentation and tumor histology are strongly correlated. In neonates and infants, there is a preponderance of immature teratomas (grade 1 or 2 immaturity) and a near-absence of malignant tumors. Conversely, among children and adults, there is a preponderance of malignant teratomas (grade 3 immaturity). No patient with a grade 0, 1, or 2 tumor (benign mature or benign immature) dies of disease, although some die with disease; when death does occur in such cases, it is generally a direct result of significant morbidity secondary to tracheal compression or a lack of development of vital structures in the neck during

fetal growth. Therefore, surgery for benign thyroid teratomas should be instituted without delay because preoperative morbidity (mass effect) and mortality are significant.30,48 Malignant teratomas exhibit a clinically malignant behavior, thus emphasizing the importance of identifying their morphology and distinguishing them from the benign mature and benign immature types of teratoma.30,52 Malignant teratomas may invade by direct extension into the esophagus, trachea, salivary glands, and/or the soft tissues of the neck. Recurrence and dissemination (usually in the lungs) are known to occur in about one-third of these patients; most of these cases are fatal. These patients are managed with radiation and chemotherapy, although treatment is palliative.30,31,35,38,39,40,41,43,44,45,46 Staging does not apply to malignant teratomas.

fetal growth. Therefore, surgery for benign thyroid teratomas should be instituted without delay because preoperative morbidity (mass effect) and mortality are significant.30,48 Malignant teratomas exhibit a clinically malignant behavior, thus emphasizing the importance of identifying their morphology and distinguishing them from the benign mature and benign immature types of teratoma.30,52 Malignant teratomas may invade by direct extension into the esophagus, trachea, salivary glands, and/or the soft tissues of the neck. Recurrence and dissemination (usually in the lungs) are known to occur in about one-third of these patients; most of these cases are fatal. These patients are managed with radiation and chemotherapy, although treatment is palliative.30,31,35,38,39,40,41,43,44,45,46 Staging does not apply to malignant teratomas.

Table 16.1 Thyroid Gland Teratoma Histologic Grading | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||

SMOOTH MUSCLE TUMORS

Smooth muscle tumors primary to the thyroid gland are defined by criteria similar to those used to define leiomyomas and leiomyosarcomas in other noncutaneous and nonuterine sites. These neoplasms are composed of cells with distinct smooth muscle differentiation histologically; the diagnosis is confirmed by immunohistochemical techniques.53

Etiology

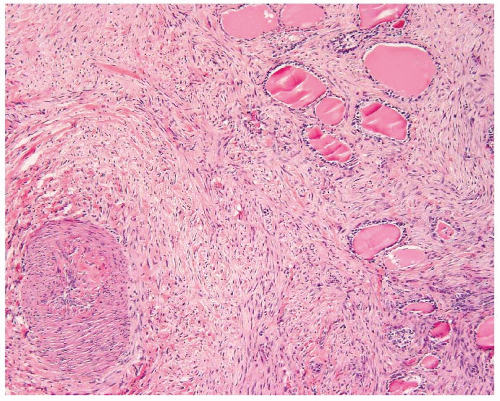

There is no known etiology for smooth muscle tumors of the thyroid gland, specifically including radiation exposure.54 A single case of an EBV-associated thyroid smooth muscle tumor has been reported in a child with a congenital immunodeficiency disease.55 No specific thyroid topographic location is seen in smooth muscle tumors, although association with smooth muscle-walled vessels at the periphery of the gland (thyroid gland capsule) has been shown (Fig. 16.15).54

Histogenesis and Molecular Genetics

Although not experimentally proven, the histogenesis of thyroid smooth muscle tumors occurs in the thyroid vessels—that is, the smooth muscle in the vascular walls (Fig. 16.15). Smooth muscle tumors are classified into cutaneous and subcutaneous, deep soft tissue, and vascular origins; the latter is the favored histogenesis for thyroid gland primaries.53,54,56

Clinical Presentation

Primary smooth muscle tumors of the thyroid gland are exceedingly rare, representing <0.02% of all thyroid gland tumors.54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66 According to reports, no patient with a leiomyoma has died of disease, but almost all patients with a leiomyosarcoma in whom follow-up was available did die from their disease.56,60,61,63,64,65,66,67,68

Unlike their benign counterparts, primary thyroid leiomyosarcomas tend to occur in older patients. In view of the limited number of cases, no predilection for either sex has been established.

Unlike their benign counterparts, primary thyroid leiomyosarcomas tend to occur in older patients. In view of the limited number of cases, no predilection for either sex has been established.

FIGURE 16.15. Smooth muscle tumor. Origin from a perithyroidal vessel wall can be seen as the neoplastic cells scroll off the muscle wall in this leiomyosarcoma. |

Patients present with nonspecific signs and symptoms. A thyroid mass, usually increasing in size (leiomyosarcoma cases), is associated with dyspnea, difficulty breathing, and/or stridor. The duration of symptoms ranges from days to years, depending on the extent of the tumor. Thyroid scans with radioactive isotopes demonstrate a cold nodule. CT reveals an inhomogeneous low-density mass in the thyroid gland; the signal intensity is similar to that of the surrounding soft tissue. Compression of the upper airway, infiltration into the soft tissues or destruction of the thyroid gland, and necrosis suggest a malignant process, but these signs are not specific for a leiomyosarcoma. In general, lymphadenopathy is absent. Ultrasonographic examination does not yield a specific diagnosis, although an ill-defined hypoechoic mass without halo has been reported.54,65

Pathology

Gross Presentation

Tumors range in size up to 12 cm in their greatest dimension; on average, leiomyosarcomas tend to be larger than leiomyomas (6 cm vs. 2 cm). Macroscopically, the outer tumor surface is smooth to nodular, depending on the diagnosis. The tumor periphery is well circumscribed to widely infiltrative into the surrounding soft tissue.54,55,56,57,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66

Microscopic Description

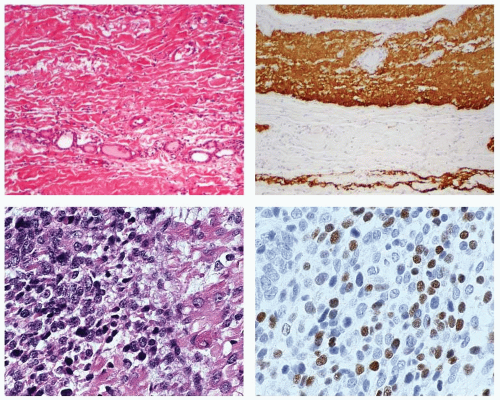

Tumor cells are arranged in bundles or fascicles of smooth muscle fibers that intersect in an orderly fashion. The cells are spindled, and blunt-ended, cigar-shaped, slightly hyperchromatic nuclei occupy a central location within the cell. Perinuclear cytoplasmic vacuoles can be seen (Fig. 16.16). In many malignant cases,

capsular invasion, vascular invasion, and perineural invasion (Fig. 16.17) are present. Entrapment of normal thyroid follicles can be seen. Leiomyosarcomas feature the morphologic characteristics of malignant smooth muscle tumors—that is, high cellularity, disordered fascicular growth pattern, and tumor necrosis (Fig. 16.17). Nuclei are markedly atypical and pleomorphic, and there is an increased number of mitotic figures (>5/10 high power fields [HPF]). Atypical mitotic figures are usually easily identified (Fig. 16.17).54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66 Electron microscopic examination of the spindle cells reveals microfilament bundles with dense patches and a discontinuous basal lamina. Grading of primary thyroid gland leiomyosarcomas has not been proposed, but doubtless would include nuclear anaplasia, increased mitotic figures, and the presence of tumor necrosis.

capsular invasion, vascular invasion, and perineural invasion (Fig. 16.17) are present. Entrapment of normal thyroid follicles can be seen. Leiomyosarcomas feature the morphologic characteristics of malignant smooth muscle tumors—that is, high cellularity, disordered fascicular growth pattern, and tumor necrosis (Fig. 16.17). Nuclei are markedly atypical and pleomorphic, and there is an increased number of mitotic figures (>5/10 high power fields [HPF]). Atypical mitotic figures are usually easily identified (Fig. 16.17).54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66 Electron microscopic examination of the spindle cells reveals microfilament bundles with dense patches and a discontinuous basal lamina. Grading of primary thyroid gland leiomyosarcomas has not been proposed, but doubtless would include nuclear anaplasia, increased mitotic figures, and the presence of tumor necrosis.

Immunohistochemistry and Molecular Diagnostics

Trichrome will reveal smooth muscle and the background collagen, although rarely performed for diagnostic purposes (Fig. 16.18). Both leiomyomas and leiomyosarcomas show myogenic immunoreactivity with smooth muscle actin (Fig. 16.18), muscle-specific actin, and desmin; vimentin is always present. Myo-D1, myogenin, and CD117 may show focal reactivity.54,61 Thyroglobulin, cytokeratin, S100 protein, chromogranin, and calcitonin are negative.54,56,60,63,68 Ki-67 fractions are increased in leiomyosarcoma, but they have not been correlated with patient survival.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree