Radical Nephrectomy

Radical nephrectomy remains the primary treatment option for renal parenchymal malignancies. As classically described, radical nephrectomy involves the en bloc resection of the structures contained within Gerota fascia, including the kidney, ipsilateral adrenal gland, perinephric fat, upper portion of the ureter, and regional lymphatics. This chapter focuses on the technical aspects and critical anatomic features of this operation. Important differences between right- and left-sided procedures are outlined. Alternative surgical options, including the laparoscopic approach and the role of subtotal nephrectomy are detailed in references at the end of the chapter.

SCORE™, the Surgical Council on Resident Education, classified nephrectomy as an “Essential Uncommon” procedure.

STEPS IN PROCEDURE

Patient in semiflank position, rotated 15 to 30 degrees posterior of vertical

Midline, bilateral subcostal, or oblique incision depending on patient habitus and size of tumor (thoracoabdominal incision may be required for large tumors)

Dissection may be purely retroperitoneal and transperitoneal

Mobilize peritoneal envelope and contents medially

Isolate and divide renal artery, followed by the vein

Adrenals may be preserved or removed with kidney, depending on circumstances and preference

Dissect in plane surrounding Gerota fascia

Identify ureter, clamp and divide as low as feasible

Regional Lymphadenectomy (If Desired)

Nodes around aorta (left-sided lesions) or inferior vena cava (left-sided lesions)

Tumor Thrombectomy (If Required)

Level I: Sweep tumor thrombus back into renal vein with fingers, secure renal vein

Level II: Isolate segment of inferior vena cava, ligate and divide all branches, anterior venotomy on cava, remove all thrombus (resect wall of cava if densely adherent)

Level III: May require cardiopulmonary bypass

Level IV: Definitely requires cardiopulmonary bypass for removal

Obtain hemostasis and close incision without drains

HALLMARK ANATOMIC COMPLICATIONS

Superior mesenteric artery mistaken for renal artery and divided

Injury to inferior vena cava

LIST OF STRUCTURES

Abdominal Wall

External oblique

Internal oblique

Transversus abdominis

Rectus abdominis

Back

Latissimus dorsi

Serratus posterior inferior

Chest

Ribs

Intercostal muscles

Intercostal vessels and nerve

Diaphragm

Pleura

Gerota fascia

Perinephric fat

Kidneys

Ureter

Regional lymphatics

Adrenal gland

Vasculature

Aorta

Vena cava

Renal artery

Renal vein

Ascending lumbar vein

Gonadal vein

Adrenal vein

Superior mesenteric artery

Inferior mesenteric artery

Liver

Cardinal ligaments

Triangular ligaments

Hepatocolic ligaments

Accessory hepatic veins

Spleen

Lenocolic ligaments

Ascending and Descending Colon

Line of Toldt

Duodenum

Pancreas

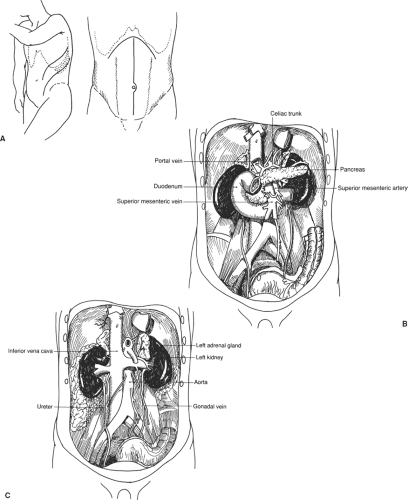

Patient Positioning and Choice of Incision (Fig. 108.1)

Technical Points

Radical nephrectomy can be performed through a variety of incisions. The choice depends to a large extent on surgeon preference, patient body habitus, tumor size, and location of the lesion within the kidney. The need for additional procedures such as caval tumor thrombectomy, contralateral renal surgery, or simultaneous resection of limited metastatic disease in the liver or lungs may also determine which incision is the most efficacious. The technical aspects, rationale, and patient positioning of each of the primary surgical approaches are discussed later. For all incisions, we prefer a multipositional self-retraining retractor such as the Omni-Tract, which allows simultaneous deep and superficial retraction.

Flank or Semiflank Incision

This approach is best suited for tumors of almost any size that are not primarily located in the upper pole and do not have associated tumor thrombus extending into the vena cava. It is especially useful in obese patients with a large abdominal pannus because the flank tends to have less subcutaneous fat than the abdomen. This incision provides direct extrapleural retroperitoneal exposure, avoiding contact with the intraperitoneal contents and, as a result, reduces the risk for postoperative ileus. Another benefit of this incision is direct posterior access to the main renal artery. Exposure can, however, be limited with larger tumors owing to the finite amount of space available for medial rotation of the kidney.

Position the patient in a semiflank position rotated 15 to 30 degrees posterior of vertical to allow extension of the incision medially across the rectus to give greater exposure when necessary. Center the patient with the kidneys over the break in the operative table and elevate the kidney rest. The legs and arms should be well padded using pillows both below the down extremity and in between. Alternatively, a sling can be used to support the upper arm. An axillary roll is placed to prevent excess traction on the brachial plexus. As with all approaches, the patient is secured to the table with Velcro straps or wide-cloth adhesive tape.

The incision can be made in several locations but usually begins off of the tip of the twelfth rib or the eleventh intercostal space for smaller tumors. Often, the higher incision is preferred because the renal hilum is deceptively cephalad in its location, despite indications on imaging studies. Division of the intercostal ligament provides excellent exposure even without resection of a rib. It is preferable to maximize exposure for larger tumors (larger than 7 cm) by performing an incision directly over the eleventh or twelfth rib and resecting it. Rib resections are performed in a subperiosteal plane, which allows bone to regenerate from the periosteum. Take care to preserve the neurovascular bundle that underlies the inferior edge of the rib. After dividing the anterior edge of the latissimus dorsi and underlying serratus posterior inferior muscle, incise the anterior periosteal layer using the cautery beginning at the edge of the sacrospinal muscle and extending along the entire rib. Raise anterior periosteal flaps with an Alexander periosteal elevator. Then elevate the rib from the posterior periosteal layer with Doyen rib elevators. Transect the rib laterally using a right-angled rib cutter and a bone rongeur to remove sharpened corners of the cut surface. Use electrocautery or apply bone wax to stop bleeding from the cut end of the rib. Release the diaphragm and pleural attachments and sweep these cephalad to avoid entering the pleural space.

Close any small inadvertent pleurotomies primarily with fine absorbable suture around a small red rubber catheter brought out through the fascial closure. After the skin is closed, submerge the open end of the red rubber catheter in a basin of water held below the level of the flank while the anesthesiologist performs several deep positive-pressure ventilations to evacuate entrapped air before tube removal.

Anterior Subcostal (Half-Chevron) Incision

This transperitoneal approach allows direct access to the vasculature without initial renal mobilization. It is particularly useful for larger tumors in almost any portion of the kidney. It may not be the optimum access, however, for extremely large upper pole tumors or in morbidly obese patients. The incision can, if necessary, be extended into a full-chevron incision to accommodate the largest renal tumors, to provide bilateral renal access, or to optimize exposure of the great vessels. This direct access to the peritoneum also facilitates exploration for metastatic disease. As with any transperitoneal approach, there is a slightly higher risk for postoperative ileus and injury to adjacent organs such as the spleen and liver than is seen with

retroperitoneal exposure. Depending on surgeon preference, the patient may be placed in a supine position with a rolled sheet beneath the upper lumbar spine or with a 45-degree angle of the chest and upper abdomen while the lower abdomen is kept as supine as possible. In this latter position, sandbags may be used behind the chest to support the position and the kidney rest and flexion of the table applied as described previously. Pillows are used to pad the lower extremities, and an airplane arm support is used to support the ipsilateral arm, which is brought across the body. The incision is begun just off the tip of the twelfth rib and extends two fingerbreadths below the costal margin with a gentle upward curve across the midline, usually ending at the contralateral rectus.

retroperitoneal exposure. Depending on surgeon preference, the patient may be placed in a supine position with a rolled sheet beneath the upper lumbar spine or with a 45-degree angle of the chest and upper abdomen while the lower abdomen is kept as supine as possible. In this latter position, sandbags may be used behind the chest to support the position and the kidney rest and flexion of the table applied as described previously. Pillows are used to pad the lower extremities, and an airplane arm support is used to support the ipsilateral arm, which is brought across the body. The incision is begun just off the tip of the twelfth rib and extends two fingerbreadths below the costal margin with a gentle upward curve across the midline, usually ending at the contralateral rectus.

Thoracoabdominal Incision

This transthoracic transperitoneal exposure is ideal for large upper pole lesions or in cases in which an ipsilateral pulmonary wedge resection of limited metastatic disease is required. It is particularly helpful for large, right-sided, upper pole tumors of which visualization and exposure may otherwise be limited owing to the overlying liver. Right-sided renal cancers with associated supradiaphragmatic tumor thrombus requiring cardiac bypass techniques can also be approached in this fashion. The disadvantage of this incision is that it requires placement of a chest tube and is often associated with increased postoperative pain. In this approach, the patient is positioned as described previously for the flank incision.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree