Pyloric Exclusion and Duodenal Diverticulization

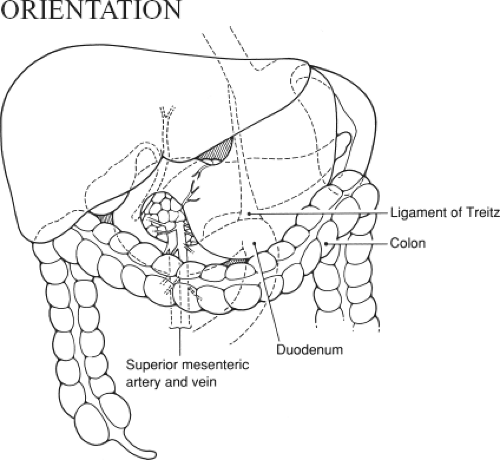

Injuries of the duodenum can be difficult to manage. In this chapter, exposure of the duodenum from the pylorus to the suspensory ligament of duodenum (ligament of Treitz) and two useful maneuvers for managing complex injuries to the duodenum are covered.

Duodenal injuries are rarely isolated, due to the central location of the duodenum (Fig. 66.1). Careful assessment of the adjacent pancreas, bile duct, colon, and neighboring vascular structures is an essential component of management.

Sometimes primary repair is all that is needed, particularly for clean isolated cuts limited to less than 50% of the circumference of the duodenum. The procedures described here are used when more severe injuries require management. A standard grading system has been developed and this facilitates classification of duodenal injuries (see references at the end).

Duodenal diverticulization is the first procedure described. It is essential for a distal gastric resection with BII reconstruction. It is rarely used, having generally been replaced by the less invasive pyloric exclusion operation. The goal of both procedures is to allow the enteric contents to bypass the duodenal repair. When properly performed, pyloric exclusion provides this bypass with less dissection in a fully reversible fashion.

SCORE™, the Surgical Council on Resident Education, classified management of duodenal trauma as an “ESSENTIAL UNCOMMON” procedure.

LIST OF STRUCTURES

Stomach

Pylorus

Duodenum

First portion (duodenal ampulla or bulb)

Second portion

Third portion

Fourth portion

Pancreas

Head of pancreas

Suspensory ligament of duodenum (ligament of Treitz)

Gallbladder

Bile duct

Colon

Ascending (right) colon

Hepatic flexure

Cecum

Transverse colon

Embryologic Terms

Foregut

Midgut

Hindgut

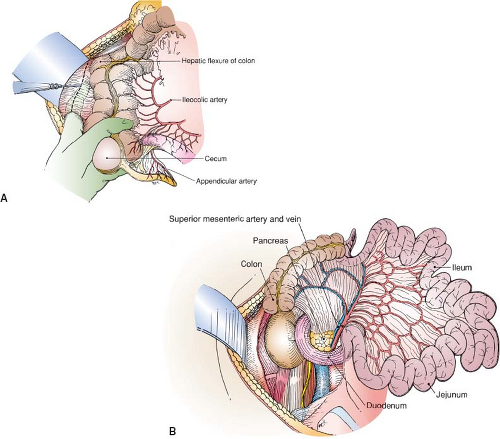

Exposure of the Duodenum (Fig. 66.2)

Technical Points

First, mobilize the hepatic flexure of the colon by incising the lateral peritoneal attachments at the hepatic flexure. Make a small window in the peritoneum with Metzenbaum scissors, then pass the fingers of the nondominant hand behind the colon, sweeping the peritoneum up and thinning it out. Divide it with electrocautery. Often, there are filmy adhesions extending to the gallbladder; divide these by sharp dissection.

If you anticipate the need to expose the entire duodenum, pass your nondominant hand down behind the ascending (right) colon and divide the lateral peritoneal reflection all the way down past the cecum. Lift the ascending (right) colon with its mesentery, sharply dividing any filmy adhesions between the colon and the retroperitoneum. The third portion of the duodenum will be visible as the colon is swept medially. Elevate the ascending (right) colon and the mesentery of the small intestine (carefully preserving the superior mesenteric vessels) and swing them toward the left shoulder of the patient. The anterior surface of the duodenum from the pylorus to the suspensory ligament of duodenum (ligament of Treitz) should now be visible.

Mobilize the duodenum and head of the pancreas using a wide Kocher maneuver to gain access to the lateral and posterior surfaces of the duodenum in these regions. The fourth portion of the duodenum may be similarly mobilized by incising the antimesenteric border.

Anatomic Points

This procedure is made necessary, as well as technically possible, by the embryologic rotation of the gut. A knowledge of this developmental process enables a rational approach to the procedure.

The gut can be divided into foregut, midgut, and hindgut. For the purposes of the general surgeon operating on the abdomen, these divisions can be defined as follows: The foregut is that portion of the gut supplied by the celiac artery, the midgut is that portion supplied by the superior mesenteric artery, and the hindgut is that portion supplied by the inferior mesenteric artery. Foregut derivatives in the abdomen include the distal esophagus, the stomach, and the duodenum to just distal to the major duodenal papilla. The liver and biliary apparatus arise as the hepatic diverticulum from the terminal foregut, whereas the pancreas arises from a diverticulum of the hepatic diverticulum and from a separate dorsal pancreatic bud. Midgut derivatives include the rest of the duodenum, all of the small intestine, the appendix, the cecum, the ascending colon, and the proximal two-thirds of the transverse colon. Hindgut derivatives include the distal one-third of the transverse colon, the descending colon, the sigmoid colon, the rectum, and the anal canal to the anal valves.

The development of the abdominal gastrointestinal tract can be understood as a consequence of two phenomena. One of these is differential growth of the gut components in comparison to each other and to the developing peritoneal cavity. The other is the fusion and later degeneration, of apposed serosal surfaces. What follows is a conceptual description of some of

the surgically relevant facets of the development of the infradiaphragmatic gastrointestinal system.

the surgically relevant facets of the development of the infradiaphragmatic gastrointestinal system.

Figure 66.2 Exposure of the duodenum

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|