The Essential Elements of Successful Plans

All successful plans have four major features:

Organize processes, procedures, and staff for efficient and effective work.

Influence and lead team members or employees who report to you.

Monitor work progress, schedules, and budgets.

Identify problems and suggest corrective actions.

The following section explores the importance of planning, the basic types of plans healthcare managers work with, the step-by-step way plans are created, and a host of special tools and techniques that can make plans more effective and efficient for everyone who utilizes them.

In today’s demanding healthcare workplace, your department, team, or workgroup needs to consistently meet goals both large and small to help improve the overall company as well as your specific group. Meeting—and, hopefully, exceeding these goals and expectations—enables your department and company to become ever better at what they do, staying one step ahead of the competition. Healthcare organizations face pressures and challenges from many sources, all of which increase the importance of good planning. External forces include competition, increased government regulations, ever-more complex technologies, the uncertainties of a global economy, and rising labor and resource costs. Internal forces include the demand for greater efficiency, increased diversity in the workforce, and the introduction of new processes, structures, and work arrangements. In today’s ever-changing work environment, good planning offers a number of benefits and advantages for your employees, your teammates, and even your own career.

Greater Focus and Flexibility

Good planning improves focus and flexibility for both you and your organization.

Focus: An organization with focus knows what it does best, knows the needs of its customers or patients, and knows how to serve them well. An individual with focus knows where he or she wants to go in a career or situation and is able to keep that objective in mind, even in difficult circumstances.

Flexibility: An organization with flexibility is willing and able to change and adapt to shifting circumstances and operates by looking toward the future (rather than the past or present). An individual with flexibility balances his or her career plans with the problems and opportunities posed by new and developing circumstances—both personal and organizational.

The Planning Process

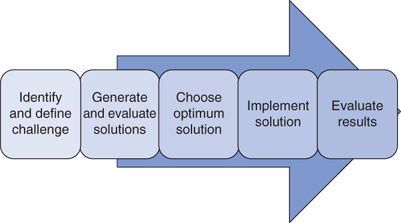

At its most basic, planning is decision making. When you plan, you use information to make plans that address significant problems and opportunities. Figure 5–1 shows a typical approach to decision making as applied during the planning process. The planning process begins with identification of a problem and ends with evaluation of implemented solutions. This section covers each step of the planning process in detail, addressing the key responsibilities of managers at each phase.

There are 5 steps in the planning process:

Step 1: Identify and define the problem.

Step 2: Generate and evaluate possible courses of action.

Step 3: Choose a preferred solution.

Step 4: Implement the solution.

Step 5: Evaluate results.

During the first step of planning and decision making—finding and defining the problem—you gather information, evaluate information, and deliberate. Problem symptoms usually signal the presence of a performance deficiency or opportunity.

During this step, you need to assess the situation properly by looking beyond symptoms to find out what is really happening. Take special care to not just address a symptom while ignoring the true problem. The way you define a problem originally can have a major impact on how you go about resolving it. Poor problem definition can lead to poor or ineffective plans, and the following three common mistakes:

Focusing on symptoms instead of causes. Symptoms indicate that problems may exist, but don’t mistake them for the problems themselves. Most managers can spot problem symptoms (like a drop in an employee’s performance). Instead of treating symptoms (such as simply encouraging higher performance), good managers need to address the symptom’s root causes (in this case, discovering that the worker’s need for additional training in how to use a complex new computer system).

Defining the problem too broadly or too narrowly. To take a classic example, the problem stated as build a better mousetrap can be more broadly defined as get rid of the mice now. That is, managers should define problems so as to give themselves the best possible range of planning options.

Choosing the wrong problem to deal with. Managers need to set priorities and make plans that deal with the most important problems first. Focusing on several small, less-important initiatives divides you and your team’s focus. Your efforts may not yield the greatest possible benefit to your department or organization. By contrast, managers also need to give planning priority to problems that are truly solvable. While many healthcare managers may want to overhaul the Medicare system, focusing on streamlining the Medicare billing processes for your department is a much more achievable goal for you and your teammates.

A variety of tools and techniques help managers identify and define problems, as we will see in a later section of this chapter.

After you define the problem, you can begin formulating one or several potential solutions. At this stage of planning and decision making, you may need to gather more information, evaluate data, analyze internally and externally gathered statistics, and weigh the pros and cons of each possible course of action. Involving others during this planning stage is critical in order to develop a range of solutions, get the most out of available information, and build future commitment for the plan.

Your plan will only be as good as the quality of the alternative solutions you generate during this step. The better the pool of alternatives, the more likely a good solution can be achieved. A very basic evaluation used at this step is

Cost-benefit analysis, which compares alternative costs (time, money, resources, human capital, etc) to the expected benefits. At a minimum, the benefits of a preferred alternative should be greater than its costs. Although cost-benefit analysis is often quantitative (based on measurable facts and figures), the results need to be tempered by your subjective, qualitative judgments to ensure full evaluation of the options.

At this stage in the planning process, you must make a decision and select a particular course of action. Exactly how you make a decision and who may need to weigh in on the decision varies for each planning situation. In some cases, you may determine the best alternative by using cost-benefit analysis criterion; share this choice with your manager, and then proceed with executing your plan. Other times, numerous criteria may come into play, and you may need to present the case for your decision to multiple committees and managers, gradually getting others to buy into your solution. However, after you generate and evaluate the alternatives, you must make a final choice to continue in the planning process.

You should test any decision to follow a particular plan of action by performing an ethics check. This evaluation ensures that you properly consider the ethical aspects of working in today’s complex, fast-changing work environment.

After you select the preferred solution to a problem, you next establish and implement appropriate actions to meet your final goal. This is the stage at which you finally set directions and initiate problem-solving actions.

Nothing new can happen according to the plan unless action is taken. Managers not only need the determination and creativity to make a plan, but they also need the ability and willingness to implement it. Additionally, most successful plans require managers and others to take some sort of action. Many plans fail at this stage because a manager didn’t adequately involve others and gain their support. Managers who use participation wisely get the right people involved in decisions and problem solving from the beginning. When they do, plans are more likely to be implemented quickly, smoothly, and to everyone’s satisfaction.

Planning and decision making are not complete until you evaluate the results. In this final stage, you compare your accomplishments with your original objectives. If the desired results are not achieved, the process must be reviewed and renewed to allow for corrective actions. Remember to examine both the positive and negative consequences of a chosen course of action. If the original solution appears inadequate, a return to earlier steps may be required to generate a modified or new plan. Evaluation is also made easier if the original plan includes objectives with measurable targets and timetables.

Planning Tools and Techniques

Planning is challenging in any circumstances, and the difficulties increase as the work environment becomes more uncertain. To help master these challenges, managers make use of a number of useful planning tools and techniques during the planning process and after a plan is put into place. Some of the most common planning tools and techniques include

Forecasting

Contingency planning

Scenario planning

Benchmarking

Participation

Strategic planning

Forecasting is the process of making assumptions about what will happen in the future. A forecast is a specific vision of the future. All good plans involve forecasts, particularly during Steps 1 and 2 of the planning process. Some forecasts are qualitative and use expert opinions to predict the future. In this case, a single person of special expertise or reputation or a panel of experts may be consulted. Other forecasts are quantitative and use mathematical and statistical analysis of data to predict future events.

In the final analysis, forecasting always relies on human judgment. Even the results of highly sophisticated quantitative forecasting still require interpretation and are subject to error. Forecasting is not planning—it is a planning tool. Treat forecasts cautiously, reviewing all information with a critical and questioning eye.

Planning always involves thinking ahead. But the more unstructured the problems and more uncertain the planning environment, the more likely that your original assumptions, predictions, and intentions may prove to be in error. Even the most carefully prepared plans may prove inadequate as experience develops. Unexpected problems and events frequently occur. When they do, plans have to be changed.

As a manager, you are better off anticipating problems than being surprised by them. Contingency planning is the process of identifying alternative courses of action that you can implement if and when an original plan proves inadequate because of changing circumstances. Sometimes contingency plans are created by good forward thinking on the part of managers and staff. At other times, a devil’s advocate method, in which you formally assume the worst-case forecasts of future events and brainstorm responses, can yield effective contingency plans. Whatever methods you use to establish contingency plans, remember that the earlier the need for changes can be detected, the better. Look for trigger points in regular processes and procedures that can indicate that your existing plan is no longer desirable and needs to be closely monitored.

Scenario planning is a popular and long-term version of contingency planning. Scenario planning involves identifying several alternative future states of affairs that may occur. Managers and staff then deal hypothetically with each situation and formulate possible plans.

The creative brainstorming process helps organizations operate more flexibly in dynamic environments. The United States Marine Corps has been doing scenario planning for many years and in fact makes it a requisite of its leadership training. The process began years ago when instructors presented officer candidates with perplexing questions based on scenarios replicating crisis and combat situations. In a healthcare setting, similar questions can be posed by creating alternative future scenarios while remaining sensitive to the nature of growing environmental changes. Although recognizing that planning scenarios can never be inclusive of all future possibilities, these scenarios help condition the organization to think and remain better prepared than its competitors for future shocks.

Another important influence on the success or failure of planning is the frame of reference used as a starting point. All too often, managers and planners have limited awareness of what is happening outside their immediate work setting. Successful planning must challenge the status quo; it cannot simply accept things the way they are.

Benchmarking is a technique that uses external comparisons to evaluate one’s current performance and identify possible future actions; it is one tool that broadens a work group and organization’s field of view. The purpose of benchmarking is to find out what other people and organizations are doing very well and plan how to incorporate these ideas into your own operations. Healthcare–specific benchmarking programs and Web sites—such as www.healthdatacheck.com—have emerged as useful tools to help healthcare managers track and compare performance.

Participation is critical to the planning process. Participative planning involves the people who are affected by a plan or who are required to help implement the plan to aid in the planning process. Participation can increase the creativity and information available for planning. It can also increase the understanding, acceptance, and commitment of people to final plans. Indeed, planning in organizations should rarely, if ever, be done by individuals. To create and implement the best plans, others must be genuinely involved during all planning steps. Even though participative planning takes more time, it can improve results by improving implementation.

A strategy is a comprehensive action plan that identifies long-term direction and guides managers and staff in ways to best utilize the organization’s resources. Successful strategic plans using resources focus an entire organization’s energies on a clear target or goal. Usually strategic plans originate in the uppermost management and executive levels of a company. Smaller, more specific plans in departments, teams, or work groups need to mesh with and build on the overarching strategic plans.

Mission statements, core values statements, and objectives are all strategic planning tools that help managers create plans that fit the organization’s vision for the future of its business endeavors.

Mission: An organization’s reason for existence as a supplier of goods and/or services to society. A good mission statement is precise in identifying where the organization intends to operate, who the organization serves, and what products or services it provides. The best organizations have clear and compelling missions. At the Breast Cancer Program of the Dana-Farber-Harvard Cancer Center, the mission is “to reduce death due to breast cancer and lengthen and improve the quality of life of women with this disease.” At Merck it is “to preserve and improve human life.”

Core values: Affect and guide the action of an organization. Often posted along with the organization’s mission statement, these values reflect the organization’s broad beliefs about what is and is not appropriate. The presence of strong core values gives character to an organization, backs up the mission statement, and helps guide the behavior of members in meaningful and consistent ways. For example, core values at Merck include corporate social responsibility, science-based innovation, honesty and integrity, and profit from work that benefits humanity.

Objectives: Direct activities toward key and specific results. Whereas a mission statement sets forth an official purpose for the organization, objectives are usually shorter-term targets against which actual performance can be measured. Examples of business objectives may include producing at a certain level of profit, gaining and holding a specific share of a market, recruiting and maintaining a high-quality workforce, or making a positive contribution to society.

SWOT Analysis

In order to produce effective plans, managers and staff must have a clear picture of what’s happening within an organization and within its greater business environment. SWOT analysis (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats) is a common tool used to analyze strengths and weaknesses inside the organization and opportunities and threats outside the organization.

A SWOT analysis begins with a systematic evaluation of an organization’s resources and capabilities. A major goal is to identify core competencies in the form of special strengths that the organization has or does exceptionally well in comparison with competitors. Simply put, organizations need core competencies that do important things better than the competition and that are very difficult for competitors to duplicate. Core competencies may be found in special knowledge or expertise, outstanding technologies, unique products, or superior distribution systems, among many other possibilities.

Strengths: The resources and capabilities an organization can use to develop competitive advantage

Weaknesses: The absence of strengths

A major strategic goal of any organization is to create processes that highlight core competencies for competitive advantage by building upon organizational strengths and minimizing the impact of weaknesses.

A SWOT analysis is not complete until opportunities and threats in the external environment are also analyzed.