Portacaval and Distal Splenorenal Shunts

A variety of portosystemic shunt procedures have been devised, attesting to dissatisfaction with the side effects. Most patients with bleeding esophageal varices are managed by endoscopic control followed by transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS); surgical shunts are employed only under extreme and special circumstances. Two procedures are discussed in this chapter: The end-to-side portacaval shunt and the distal splenorenal (Warren) shunt. Other shunting and nonshunting alternatives for control of variceal bleeding are described in the references cited at the end of this chapter.

The end-to-side portacaval shunt immediately and reliably decreases portal pressure by completely diverting portal inflow into the systemic venous circulation. This shunt diminishes blood flow to the liver in cirrhotic patients with hepatopedal flow and may produce or worsen hepatic encephalopathy. Subsequent liver transplant is made much more difficult by this or any other central shunt. Technically; however, it is significantly easier and quicker than the distal splenorenal shunt. The distal splenorenal shunt selectively decompresses esophageal varices with less disturbance to portal flow. It is thus sometimes termed a “selective” shunt. Over time, this shunt loses its selectivity.

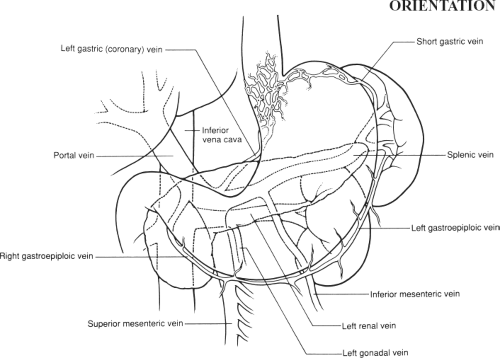

These procedures depend upon an understanding of the anatomy of both the caval system and the hepatic portal system. In general, the caval system drains the body wall, extremities, head and neck, urogenital system, and liver; all components ultimately drain into the superior and inferior venae cavae. The hepatic portal system conveys blood from the capillary beds of the abdominal gastrointestinal tract, biliary apparatus, pancreas, and spleen to the sinusoids of the liver. After passing through the hepatic sinusoids, blood is conveyed to the inferior vena cava by the hepatic veins.

Although the caval and portal systems are functionally and morphologically considered to be separate entities, there are several actual or potential sites of anastomosis between the two that can provide collateral routes if the portal system is obstructed. These include the following.

The esophageal tributaries of the left gastric vein (portal) with the esophageal tributaries of the azygos or hemiazygos vein (caval) (Fig. 80.1)

The anal tributaries of the superior rectal (hemorrhoidal) vein (portal) with the anal tributaries of the middle and inferior rectal (hemorrhoidal) veins (caval)

The left umbilical and paraumbilical veins (portal) with the superficial epigastric veins (caval)

The veins of Retzius on bare areas of the liver and the nonperitonealized surfaces of the colon, duodenum, and pancreas (portal) with the retroperitoneal branches of the intercostal, lumbar, and renal veins (caval)

SCORE™, the Surgical Council on Resident Education, classified portosystemic shunt as a “COMPLEX” procedure.

STEPS IN PROCEDURE—PORTACAVAL SHUNT

Right subcostal incision extended across midline

Divide ligamentum teres hepatis

Measure omental vein pressure

Fully mobilize duodenum, ligating collateral veins

Clean anterior surface of inferior vena cava for sufficient length to allow partial occlusion clamp

Retract duodenum medially and identify portal vein

Clean and mobilize portal vein

Clear any soft tissue between portal vein and inferior vena cava

Clamp and divide portal vein

Ligate or oversew stump at hilum of liver

Trim portal vein to proper length

Create end-to-side anastomosis between portal vein and inferior vena cava

Open anastomosis and recheck omental vein pressure

Check hemostasis

Close abdomen without drains

Prepyloric veins

Gastroepiploic Arcade

Left and right gastroepiploic veins

Suspensory ligament of duodenum (ligament of Treitz)

Pancreas

Duodenum

Colon

Left Renal Vein

Left gonadal vein

Left suprarenal (adrenal) vein

Portacaval Shunt

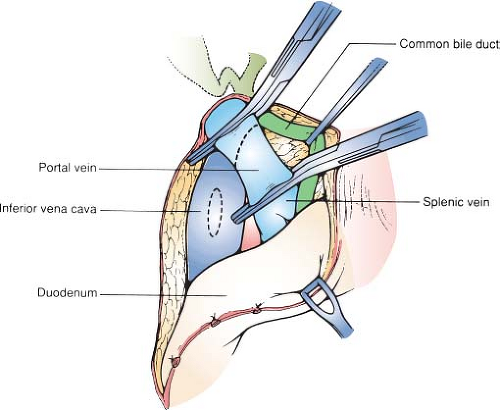

Incision and Mobilization of the Duodenum and Exposure of the Inferior Vena Cava (Fig. 80.2)

Technical Points

Position the patient supine. Place a folded towel under the lower thoracic spine or elevate the kidney rest slightly. Make a right subcostal incision and carry it across the midline, sloping it downward to follow the left costal margin. Divide the ligamentum teres hepatis with suture ligatures to secure the umbilical vein. This is generally recanalized in patients with portal hypertension and may be quite large.

Measure portal pressure by cannulating an omental vein with a 20-gauge Angiocath and connecting this to a manometer calibrated for venous pressure measurements. Ligate the

omental vein after you withdraw the cannula. Perform a needle biopsy of the liver (if this was not done preoperatively) and explore the abdomen.

omental vein after you withdraw the cannula. Perform a needle biopsy of the liver (if this was not done preoperatively) and explore the abdomen.

Figure 80.2 Portacaval shunt: Incision and mobilization of the duodenum and exposure of the inferior vena cava |

Next, perform a wide Kocher maneuver to expose the inferior vena cava fully. Do this with caution, because dilated venous collaterals may have formed in the retroduodenal area. If the retroperitoneum is thickened and the inferior vena cava is not visible, first orient yourself by palpating the abdominal aorta. The inferior vena cava will lie immediately to the right of the aorta. Generally, it will be directly deep to the hepatoduodenal ligament, another useful landmark. Often, the invisible inferior vena cava is palpable as a large ballottable structure after the proper location has been identified. Clean the anterior surface of the vena cava by sharp dissection in the anterior adventitial plane to the level of the liver superiorly. Select a large clamp for partial occlusion, such as a Satinsky clamp, and verify that sufficient vena cava has been prepared for it to lie comfortably. Although it is not necessary to mobilize the inferior vena cava fully and circumferentially, comfortable placement of the partial occlusion clamp is easier if an adequate segment of the vena cava has been cleared as far laterally as possible.

Anatomic Points

The ligamentum teres hepatis, located in the free edge of the falciform ligament, passes from the umbilicus to the umbilical portion of the left branch of the portal vein. This fibrotic remnant of the left umbilical vein retains a lumen that normally is completely occluded only close to the portal vein. In cases of portal hypertension, this occlusion can be opened, and the residual lumen can become greatly dilated. In addition to this, the ligamentum teres hepatis is accompanied by slender paraumbilical veins that provide a portacaval anastomosis; engorgement of these veins leads to the classic caput medusae. Thus control of all these veins must be achieved before division of the ligamentum teres hepatis.

Omental veins are tributaries of the right or left gastroepiploic veins. Because of the proximal and distal communications between the omental veins, as well as the fact that the portal system is typically valveless, ligation on both sides of the cannula site is necessary for adequate hemostasis.

Visualization of the inferior vena cava in the upper abdomen is possible only if the duodenum and head of the pancreas are kocherized. The portal venous tributaries that will be mobilized with these organs are the retroduodenal vein, pyloric (right gastric) vein, supraduodenal vein, the pancreaticoduodenal veins, and the superior mesenteric vein. These will be engorged and fragile. In addition, several direct communications, via the veins of Retzius, between the portal and caval systems will most likely be enlarged and must be divided. These should be divided with care to prevent their avulsion from the inferior vena cava or its major tributaries.

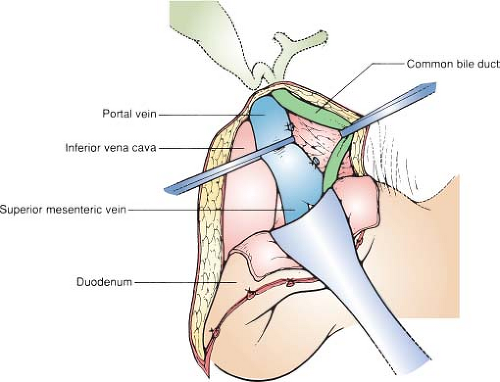

Dissection of the Portal Vein (Fig. 80.3)

Technical Points

Rotate the duodenum medially to expose the posterior aspect of the hepatoduodenal ligament. Place a moist laparotomy sponge over the posterior duodenum and head of the pancreas and place a retractor there. Have your assistant apply gentle traction to maintain these structures up, in a fully kocherized position. Palpate the posterior surface of the hepatoduodenal ligament, which has been rotated upward toward you by retraction, and identify the portal vein. It is a large, soft, ballottable structure posterior to the bile duct and hepatic artery. Incise the

peritoneum overlying the posterolateral surface of the portal vein and enter the anterior adventitial plane of the vein.

peritoneum overlying the posterolateral surface of the portal vein and enter the anterior adventitial plane of the vein.

All of the tributaries of the portal vein in this vicinity pass to the left (anteromedial). The right or “free” edge (i.e., the edge of the vein corresponding to the free edge of the hepatoduodenal ligament) is without tributaries. Therefore, dissect proximally and distally along the vein in this region first. Use a peanut sponge to gently develop the plane partially around the portal vein. Use a vein retractor to elevate the bile duct, hepatic artery, and soft tissues from the anterior surface of the portal vein. Carefully dissect in the adventitial plane of the portal vein until it can be gently elevated and surrounded by a vessel loop. Mobilize the vein cephalad to the hilum of the liver and caudad to the vicinity of the splenic vein. Divide several small tributaries that pass to the left.

Visualize the path that the portal vein will need to take to anastomose with the inferior vena cava. Divide and excise any thickened soft tissue lateral and posterior to the portal vein, if necessary, to create a groove in which the vein can lie without kinking.

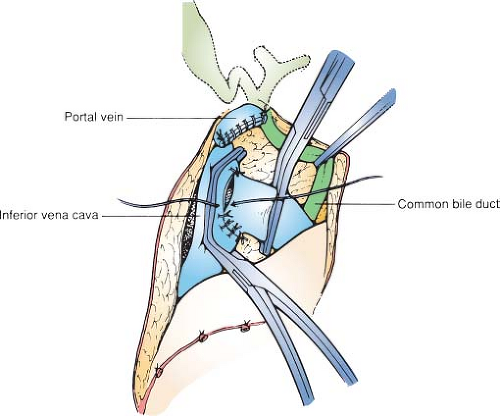

Divide the portal vein between the vascular clamps at the hilum of the liver, leaving sufficient length in the hilum to safely ligate or oversew the stump. A medium-sized, slightly angled vascular clamp provides good control over the portal vein and can be used by your assistant to hold the vein in the best possible position for anastomosis. Bulldog-type clamps are not useful in this situation because they allow too much mobility of the vein. Suture material will tend to catch in the spring of the clamp, as well.

Preoperative, venous phase angiographic studies will generally have demonstrated patency of the portal vein. Sometimes; however, an unexpected thrombus is encountered. In such cases, an attempt at gentle extraction of the thrombus from the vein using forceps is often successful. Ligate the vein and then place a second transfixion suture ligature below the initial site of ligation for security.

Anatomic Points

The portal vein is formed dorsal to the neck of the pancreas by the union of the superior mesenteric and splenic veins. It then passes posterior to the first part of the duodenum and runs in the right border of the hepatoduodenal ligament to the porta hepatis, where it divides into left and right branches. From its origin to its terminal branches, this vein is 8 to 10 cm long and 8 to 14 mm in diameter. Initially, it is somewhat to the right of the beginning of the superior mesenteric artery and anterior to the inferior vena cava. As it ascends in the hepatoduodenal ligament, it lies posterior to both the bile duct (closest to the free edge of the hepatoduodenal ligament) and the hepatic artery complex. The gastroduodenal artery usually arises from the common hepatic artery to the left of the portal vein, then crosses the anterior surface of the vein before it branches into the superior pancreaticoduodenal and right gastroepiploic arteries. Because of these relationships, the portal vein is most easily approached from its posterior surface. However, the surgeon should be aware that aberrant right hepatic arteries (e.g., those arising from the superior mesenteric artery or independently from the celiac artery) almost invariably lie posterior to the portal vein.

Tributaries of the portal vein vary considerably. In addition to the splenic and superior mesenteric veins, frequently, the left gastric (coronary), right gastric (pyloric), prepyloric, paraumbilical, accessory pancreatic, and cystic veins drain directly into the portal vein. Of these, the only one of significant size is the left

gastric vein, which enters from the left in approximately 25% of cases. In the remaining 75% of cases, it terminates in the splenic vein, usually very close to the confluence of the splenic and superior mesenteric veins. Other tributaries tend to enter the anterior surface of the vein. The right side, which is the side along the free edge of the hepatoduodenal ligament, usually has no tributaries.

gastric vein, which enters from the left in approximately 25% of cases. In the remaining 75% of cases, it terminates in the splenic vein, usually very close to the confluence of the splenic and superior mesenteric veins. Other tributaries tend to enter the anterior surface of the vein. The right side, which is the side along the free edge of the hepatoduodenal ligament, usually has no tributaries.

Figure 80.4 Construction of anastomosis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|