Plague

Anthony J. Carbone

NAME OF AGENT

Disease: Plague; Organism: Yersinia pestis.

MICROBIOLOGY

The disease known as plague is caused by Yersinia pestis, a bacterium of the Enterobacteriaceae family. The plague bacillus is a small, ovoid, nonmotile, nonspore-forming, nonlactose-fermenting, gram-negative, rod-shaped bacterium. Bipolar uptake occurs when using Wayson, Wright, Giemsa, methylene blue, and occasionally gram-stained preparations, revealing the classic “safety pin”-shaped coccobacilli under magnification (Fig. 7-1) (1,2)

THEORETICAL AND SCIENTIFIC BACKGROUND

BRIEF HISTORY

Plague is a zoonotic disease (animal disease that is naturally communicable to humans) caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis. Plague has been responsible for three great pandemics of human disease occurring in the 6th, 14th, and 20th centuries of the modern era, resulting in the deaths of millions and changing the course of history (3).

The first pandemic, known as the Justinian Plague, began in the port cities of Egypt in 541 a.d. and spread throughout the Mediterranean basin, the Middle East, and Europe, killing an estimated 50% to 60% of the population before it ran its course in 545 a.d. and decimated the Eastern Roman Empire (4).

The second plague pandemic, known as the Black Death, is believed to have originated in Mongolia around 1320 and spread throughout the occupied world over the next 130 years killing approximately one-third of the world’s population at the time (5,6,7).

Figure 7-1. Gram stain. Yersinia pestis, gram-negative bacillus at 1,000X. (From Centers for Disease Control-PHIL; Date: 2002.) |

The third plague pandemic erupted in China in 1855, killing 12 million people in China and India alone, before reaching San Francisco’s Chinatown in 1900 (8). During the next 4 years 121 people in California were infected, killing all but three. A secondary plague epidemic erupted in San Francisco in 1907 with 160 cases and 77 deaths (9). Since the San Francisco epidemics, plague has been endemic in the United States, predominantly in the southwestern states.

Because of plague’s legacy of death, devastation, and fear, armies throughout the centuries have tried to exploit Yersinia pestis as a weapon of war. The first documented use of plague as a military weapon was during the siege of Kaffa, a Crimean port city on the Black Sea, during the year 1346. The besieging Tartars catapulted the corpses of their own plague victims into the city. The Genoese fled Kaffa and returned to Italy bringing plague along with them and very likely starting the Black Death in Europe (10,11,12,13). This practice was repeated as late as late as 1710 when the Russians used the same tactic against the Swedes in the Russian-Swedish War of 1700–1725 during the Siege of Revel (14).

During the 1930s and 1940s, the Japanese Imperial Army experimented with plague within its secret biological weapons program in occupied Manchuria. Approximately 3,000 scientists under the direction of Japanese General Ishii Shiro, a military physician and microbiologist who was fascinated with plague, worked to weaponize Yersinia pestis. Japanese Unit 731 operated a plague flea factory in Manchuria with 4,500 breeding machines, producing about 100 million plague-infected fleas every few days. The Japanese Unit 100 reportedly dropped plague-infected fleas over China resulting in a number of plague outbreaks where none had previously occurred (15,16,17).

The United States studied plague as a potential weapon in the 1950s before its offensive program was terminated by President Richard Nixon in 1969 (18). In 1972 the United States, the Soviet Union, and one hundred other countries signed the Biological Weapons Convention (19). Shortly after the treaty was signed, the Soviet government initiated a massive clandestine offensive biological weapons program under the name Biopreparat that researched, weaponized, tested, produced, and stockpiled tons of deadly biological agents, including a multidrug-resistant weaponized form of plague that could be easily aerosolized (20,21).

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF NATURALLY OCCURRING PLAGUE

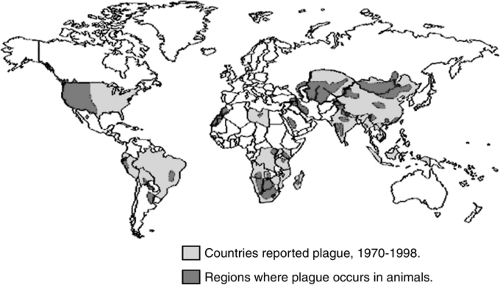

Naturally occurring plague is primarily a disease of rodents, which is transmitted to humans in sporadic cases and epidemics. Natural infestation occurs in a variety of susceptible host rodents such as the infamous Rattus rattus (22), the black house and ship rat, and other animals including ground and tree squirrels, prairie dogs, and carnivores such as coyotes, bobcats, dogs, and cats (23). Plague is a naturally occurring enzootic infection of rats, prairie dogs, and other rodents on every populated continent except Australia (24). On average, there have been approximately 1,700 cases a year reported worldwide in the past 50 years (25). India experienced a major plague outbreak in 1994 in the industrial city of Surat following a severe earthquake. When it was over, 56 people were reported to have died from plague, while some 6,500 individuals were treated with antibiotics (Fig. 7-2) (26).

Plague has been endemic within the continental United States since it was first observed in California in 1907 (27,28). The last major outbreak of plague in the United

States occurred in Los Angeles in 1924–1925 when 40 people were infected and only two survived (29). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report an average of 13 cases of plague annually with the majority of cases occurring within the four southwestern states of New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, and California (Fig. 7-2). In a 1997 study published by the CDC, 390 cases of plague were reported in the United States from 1947 to 1996. Of these cases, 84% were reported as bubonic, 13% were septicemic, and 2% were pneumonic plague; case fatality rates were 14%, 22%, and 57%, respectively (30).

States occurred in Los Angeles in 1924–1925 when 40 people were infected and only two survived (29). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report an average of 13 cases of plague annually with the majority of cases occurring within the four southwestern states of New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, and California (Fig. 7-2). In a 1997 study published by the CDC, 390 cases of plague were reported in the United States from 1947 to 1996. Of these cases, 84% were reported as bubonic, 13% were septicemic, and 2% were pneumonic plague; case fatality rates were 14%, 22%, and 57%, respectively (30).

Figure 7-2. World distribution of plague, 1998. (From CDC plague web site, Division of Vector-Borne Infectious Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvbid/plague/epi.htm.) |

Most cases of plague in humans occur in the summer months when the risk for exposure to infected fleas is greatest (31). Most cases of plague in the United States have been in men younger than 20 years old (32), and occurred within a 1-mile radius of their homes (Fig. 7-3) (33).

Figure 7-3. Reported human plague cases by county: United States, 1979–1997. (From CDC plague web site, Division of Vector-Borne Infectious Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvbid/plague/epi.htm.) |

TRANSMISSION

Infected Fleas

Although plague bacilli can be found in the feces and urine of infected animals, and one can become infected by feeding upon or even handling the flesh of infected animals, human plague is most commonly transmitted by infected fleas (34,35,36). Historically, the oriental rat flea, Xenopsylla cheopis, is believed to have been largely responsible for the spread of bubonic plague (37); however, some 200 species of animals and 80 species of fleas have been associated with plague transmission worldwide (38). The most important vector of human plague in the United States is the flea Diamanus montanus, the most common flea on rock squirrels and California ground squirrels (39). Plague vector fleas prefer the blood of their rodent hosts, but if the rodent population begins to thin, the fleas will switch to human hosts for survival. Large numbers of rodents usually die off prior to human epidemics, precipitating the transfer of the flea population from its natural rat reservoir to humans (Fig. 7-4) (40).

Direct Contact

Plague can be transmitted directly to humans by handling an infected animal, dead or alive, or by stumbling into an infected animal’s nest while walking. Rock squirrels and California ground squirrels are known to infect man via direct contact and fleas. Fur trappers often develop plague via direct contact while skinning infected animals (41,42,43,44).

Human-to-Human Transmission

Human-to-human transmission of plague is rare, but it can occur from close contact with patients coughing from pneumonic plague. Respiratory transmission is thought to occur more efficiently via larger droplets or fomites rather than from small-particle aerosols (45). The last case of human-to-human transmission of plague in the United States occurred during the Los Angeles epidemic of 1924 (46).

Deliberate Aerosol Attack

The deadliest method of transmission would be via a deliberate attack using aerosolized plague over a large area. Japanese General Ishii Shiro attempted to initiate plague outbreak over China during World War II using ceramic bombs filled with plague-infected human fleas, Pulex irritans, to target humans directly with the hope of creating a plague outbreak (47,48,49,50). During the 1970s and 1980s, the Soviet Union’s secret biological weapons (BW) program perfected the methodology by first developing a multidrug-resistant plague bacillus and then weaponizing the agent so that it could be preserved and stored into a variety of warheads and aerosolized easily when over a target area (51,52). Despite the fall of the Soviet Union, and the reported dismantling of the BW program, this method of aerosol transmission poses the greatest threat to mass casualties of pneumonic plague today.

PATHOGENESIS IN NATURALLY OCCURRING PLAGUE

In the majority of cases of naturally occurring plague, a flea such as Xenopsylla cheopis survives by living off of a host rodent like the ground squirrel. If the rodent is infected with plague, the flea draws viable Yersinia pestis organisms into its esophagus during a feed. The bacteria then multiply in the flea’s stomach. If the host rodent dies, it looks for new hosts and this is when man is most likely to be bitten by an infected flea. When the flea bites the skin of a person and begins to feed, plague bacilli are mixed with the blood drawn from the host and regurgitated into the bite. The flea may also discharge infected feces into the bite wound (53).

The flea’s bite leads to an inoculation of up to thousands of plague bacilli into the victim’s skin. [As few as 1 to 10 Yersinia pestis organisms are sufficient to infect rodents and primates via oral, subcutaneous, intradermal, and intravenous routes (54).] The bacteria infiltrate through the cutaneous tissue into the cutaneous lymphatic vessels and deposit into regional lymph nodes where they are phagocytosed but resist destruction. During the incubation period, lasting 2 to 8 days, the bacteria multiply rapidly causing suppurative lymphadenitis, which manifests as the characteristic bubo.

Without treatment, the lymph node architecture is destroyed resulting in bacteremia and septicemia spreading plague to other organs (55,56). The tissues most commonly infected include the spleen, liver, lungs, skin, and mucous membranes (57). The endotoxin of Yersinia pestis contributes to the development of septic shock in a manner similar to other forms of gram-negative sepsis leading to disseminated intravascular coagulation, shock, and coma (58,59).

Much less is understood about the pathogenesis of pneumonic plague. Estimates of infectivity via the respiratory route are in the range of 100 to 500 organisms for primary pneumonic plague (60,61). Secondary pneumonic plague occurs in untreated cases of bubonic plague that lead to septicemia and seeding of pulmonary tissue.

CLINICAL FORMS OF PLAGUE

Bubonic Plague: In the United States, most patients (approximately 85%) with human plague present clinically with the bubonic form. Bubonic plague arises from the bite of an infected flea and the bacteria become localized in an inflamed lymph node (femoral, inguinal, or axillary depending upon the site of the bite) where the bacteria replicates.

Septicemic Plague: A smaller number of patients (approximately 15%) will develop gram-negative sepsis without evidence of a bubo in what is termed “primary septicemic plague.”

Pneumonic Plague: Primary pneumonic plague occurs from the inhalation of Yersinia pestis bacteria passed from humans or cats suffering with pneumonic plague (approximately 2% of all cases). This is the form of plague that would be expected following a deliberate attack using aerosolized Yersinia pestis and is nearly always fatal if not treated quickly. Secondary pneumonic plague arises from poorly treated bubonic or septicemic plague when Yersinia pestis bacteremia seeds pulmonary tissues.

Plague Meningitis: Plague meningitis is seen in 6% to 7% of all cases of plague, usually in children following ineffective treatment. Symptoms are similar to other forms of acute bacterial meningitis.

Pharyngeal Plague: On extremely rare occasions, individuals may develop a plague pharyngitis following the inhalation or ingestion of plague bacilli. Pharyngeal plague mimics tonsillitis associated with cervical lymphadenopathy (the cervical bubo).

INCUBATION PERIODS

The incubation period for bubonic plague from flea bites is 2 to 8 days before symptoms develop. The incubation period for septicemic plague can be shorter at 1 to 7 days. The incubation period for pneumonic plague following respiratory exposure to an aerosol is usually 2 to 4 days (62).

MORTALITY RATES

The mortality rate of plague varies based upon a variety of factors including the mode of inoculation, the amount of bacterial inoculation, the age and health of the infected person, and whether or not the agent is natural or has been genetically engineered (63,64). The historical mortality rate of untreated bubonic plague is approximately 60%, with death occurring within 10 days of onset (65,66). The mortality rate for bubonic plague drops to less than 5% with early appropriate antibiotic therapy (67), whereas untreated septicemic and pneumonic plague have mortality rates of nearly 100%. In fact, even with modern antibiotic therapy, survival is unlikely if treatment is delayed more than 18 hours following respiratory exposure (68).

PLAGUE FOLLOWING DELIBERATE USE AS A BIOLOGICAL WEAPON

Clinicians and public health officials need to realize that the epidemiology of disease for a deliberate attack using plague as a biological weapon would differ substantially from a naturally occurring outbreak of plague. Intentional dissemination of plague will most likely involve the use of an aerosol of Yersinia pestis in order to inflict large numbers of casualties with deadly pneumonic plague. Victims of such an attack would present with symptoms resembling a host of other severe respiratory diseases making the initial diagnosis of plague difficult.

The indications that plague had been intentionally disseminated would include (a) the presence of plague in areas not known to have endemic enzootic infection, (b) the absence of prior rodent deaths, and (c) severe rapidly progressive respiratory disease in a number of previously healthy individuals, suggestive of pneumonic plague.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

BUBONIC PLAGUE

The pathognomic sign of bubonic plague is a very painful, swollen, warm-to-touch, lymph node called a bubo. This sign accompanied with fever, malaise, exhaustion, and a history of possible exposure to rodents, fleas, wild rabbits, or sick or dead carnivores should lead to the suspicion of plague.

Patients typically develop symptoms of bubonic plague 2 to 8 days following the bite from an infected flea. There is usually sudden onset of fever, chills, and weakness, followed by the formation of the tell-tale bubo up to one day later (69). Since fleas usually bite a person on the lower extremities, femoral and inguinal buboes are most common. Infections from skinning infected animals usually produce axillary buboes.

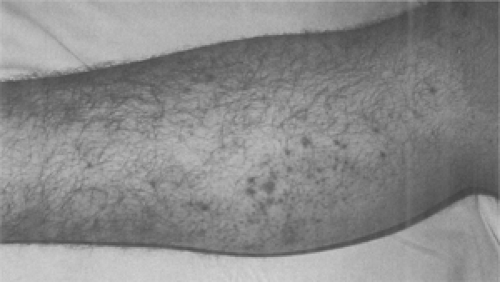

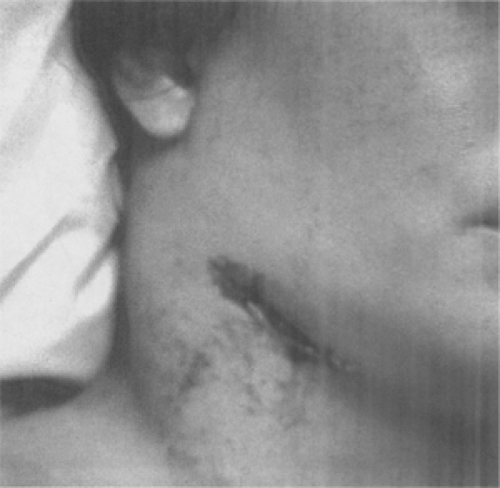

Buboes can grow from 1 to 10 cm in size and can be so painful that they prevent the patient from moving the effected site (70). The overlying skin is erythematous, warm, and extremely tender. There is often a considerable amount of surrounding edema, but rarely lymphangitis. The buboes are usually nonfluctuant, but may point, ulcerate, and drain spontaneously. Rarely, necrosis is present at which point the bubo will require incision and drainage (71,72). Approximately 4% to 10% of bubonic plague patients are reported to have a visible ulcer or pustule at the flea inoculation site (73,74). Buboes usually recede in 10 to 14 days if treated appropriately with antibiotics and generally do not require incision and drainage beyond diagnostic aspiration (Fig. 7-5,Fig. 7-6,Fig. 7-7) (75).

SEPTICEMIC PLAGUE

A small portion of patients who have been bitten by an infected flea develop Yersinia pestis septicemia without a discernable bubo in the form of the disease known as primary septicemic plague (76). Septicemia can also develop secondary to bubonic plague in what is termed secondary septicemic plague (77).

Figure 7-5. Femoral bubo. This plague patient is displaying a swollen, ruptured inguinal lymph node, or bubo. (From Centers for Disease Control-PHIL; Date: 1993.) |

Figure 7-6. Axillary bubo. An axillary bubo and edema exhibited by a plague patient. (From Centers for Disease Control-PHIL; Date: 1962.) |

Figure 7-7. Cervical bubo. Plague patient whose symptoms include this swollen, ulcerated cervical lymph node. (From Centers for Disease Control-PHIL; Date: 1993.) |

Frequently, the plague infection spreads hematogenously resulting in capillary fragility and causing cutaneous petechiae and ecchymoses, which can mimic meningococcemia (78). Plague septicemia can produce small artery thromboses in the acral vessels of the nose and digits, resulting in gangrene and complete necrosis (79). Black necrotic appendages and more proximal purpuric lesions caused by endotoxemia are often present (80). These signs are believed to be responsible for the term “black death” during the second plague pandemic (81). Unfortunately, the late finding of acral gangrene will not be helpful in the early diagnosis of plague when life-saving antibiotics should be given (Fig. 7-8 and Fig. 7-9) (82).

PNEUMONIC PLAGUE

Symptoms of pneumonic plague begin after an incubation period of 1 to 6 days (average of 2 to 4 days) and include sudden-onset of high fever, chills, headache, malaise followed by cough, often with hemoptysis, chest pain, and dyspnea (83,84,85). Patients develop progressive dyspnea, stridor, and cyanosis. Patients with terminal pneumonic or septic plague develop livid cyanosis (86,87). Death results from respiratory failure, circulatory collapse, and bleeding diathesis if the condition was not diagnosed early and treated properly (88). During pre-antibiotic era epidemics, the average time from respiratory exposure to death from pneumonic plague in humans is reported to be from 2 to 4 days (89).

Primary pneumonic plague rarely occurs in the United States. There have been two such cases in the United States in the past 20 years, both occurring after handling domestic cats with pneumonic plague. Both patients complained of typical pneumonic symptoms, but they also complained of prominent gastrointestinal symptoms of nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and diarrhea. Diagnosis was delayed more than 24 hours after symptom development in both cases, and both patients died (90,91).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree