Perimalleolar Bypass and Hybrid Techniques

Geetha Jeyabalan

Rabih A. Chaer

DEFINITION

Perimalleolar bypasses are defined by the anatomic location of the distal target outflow vessel. Perimalleolar bypasses refer to any bypass in which the distal target vessel of revascularization is the posterior tibialis, anterior tibialis, or peroneal arteries at the level of the ankle. The pedal vessels (dorsalis pedis, posterior tibialis, lateral or medial plantar artery) are also target vessels in some patients with very distal disease.

These bypasses are performed in patients with advanced critical limb ischemia (CLI), which includes tissue loss, or ischemic rest pain for which there is not a durable or feasible endovascular option. With the advent of advanced endovascular techniques, the indications for perimalleolar or tibial bypasses are evolving. The inflow vessel and conduit chosen are tailored to individual patients and their anatomic limitations.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The three major etiologies of lower extremity ulceration include ischemic, neuropathic, and venous stasis disease. Although all of these can have poor perfusion as a primary contributing factor, the diagnostic workup and management may be slightly different. Arterial ulcerations typically have a punched-out dry appearance and usually occur on the distal forefoot and toes, whereas neuropathic ulcerations often occur on pressure points and are associated with calluses. Venous stasis ulcerations are typically located on the medial or lateral malleolus and have associated skin changes and brawny induration in addition to serous drainage.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Patients with CLI typically present with ischemic rest pain and/or tissue loss or forefoot gangrene. Most of these patients have significant comorbid conditions such as diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension that will be important for risk stratification and in deciding between different revascularization modalities. Additionally, managing and optimizing these risk factors are keys to successful outcomes following lower extremity revascularization, regardless of the technique used. As such, optimizing lipid profile, glycemic control, smoking cessation; minimizing renal dysfunction; and managing hypercoagulable states are all essential components to the perioperative medical management, in addition to managing any concomitant coronary disease. The majority of patients are already followed by a team of physicians for their comorbidities (primary care physician, cardiologist, endocrinologist, nephrologist), whereas the surgical team is evaluating the peripheral vascular disease. It is imperative that these consultants remain actively involved in the perioperative period for both the short-term and long-term success of limb salvage and overall survival. The age of the patient, functional status, and comorbidities guide the vascular surgeon’s decision making in terms of the type of revascularization offered to the patient.

Most patients presenting as outpatients will have a history of symptoms of disabling claudication, rest pain, or tissue loss. Taking a careful history noting duration of symptoms, level of pain/claudication, areas of tissue loss, and history of traumatic neuropathic ulceration will guide the workup. Young patients, younger than 60 years of age, or patients with multiple arterial/venous thromboses should undergo a thrombophilia evaluation. Physical examination should include a thorough peripheral vascular examination, including assessment of the potential presence of a palpable aortic aneurysm on abdominal exam. The quality and symmetry of pulses and/or handheld Doppler signals between both legs at the femoral, popliteal, and pedal levels assist in determining the anatomic level of disease. Wound documentation, when present, should note location, depth, presence of infection, bone exposure, and extent of soft tissue defects. Neuropathic deformities of the foot should also be taken into careful consideration for offloading purposes. If there is gross purulence or systemic signs of infection, a debridement of the affected area is required prior to revascularization, even if the area is malperfused, for source sepsis control.

The location and appearance of ulcerations will often assist in differentiating ischemic, neuropathic, or decubitus wounds. Location of the ischemic wound is important in determining which target vessel will be chosen for revascularization. If the history and physical examination suggest peripheral vascular disease as the primary diagnosis, then noninvasive vascular testing is the next step in determining need for revascularization and level of disease.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

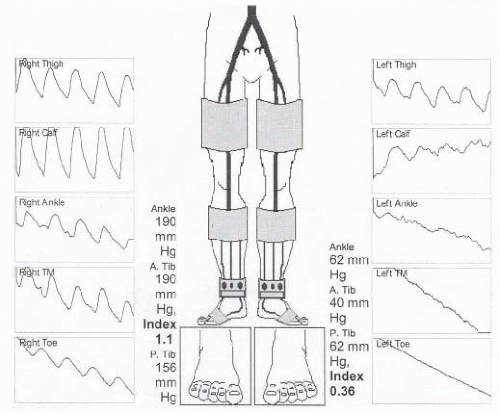

After a thorough history and physical examination, the diagnostic workup of patients with ischemic ulcerations, rest pain, or significant claudication involves noninvasive vascular testing. This involves calculation of ankle-brachial indices and pulsed volume recordings in addition to duplex imaging of the extremity. An ankle-brachial index (ABI) of less than 0.4 is typically seen in patients with CLI (FIG 1). Toe pressures of less than 40 mmHg suggest inadequate perfusion for wound healing. In cases of severely calcified vessels, it is important to obtain associated pulsed volume recordings and toe pressures because ABIs can be falsely elevated due to vessel incompressibility. Transcutaneous oxygen tension (TcPO2) measurement can also be used to determine the severity of ischemia and probability of wound healing.

Once the history, physical examination, and noninvasive testing are complete, the surgeon must determine the next step in imaging, which may be both diagnostic and therapeutic. The patient’s functional status, cardiac risk profile, and other comorbidities (ambulatory status, etc.) will all play an important role in determining whether any revascularization attempt is even feasible. If femoral pulses are not palpable on physical examination and noninvasive testing is also suggestive of inflow disease, computed tomography arteriography (CTA) may be instrumental in evaluating the extent of aortoiliac disease, taking into account renal function and risk of contrast-induced nephrotoxicity. Alternatively, aortography obtained from contralateral femoral access or upper extremity arterial access may suffice. General management approaches to aortoiliac versus infrainguinal disease are discussed elsewhere in this book.

Once the clinical determination is made that the level of disease is infrainguinal, digital subtraction angiography is an excellent diagnostic test and provides access for therapeutic intervention as well. This chapter focuses on patients with multilevel infrainguinal disease who, presumably, have either failed endovascular revascularization, prior open bypass, or who have no endovascular options for revascularization. Therefore, the primary goal of diagnostic angiography is to assess the caliber and quality of inflow vessels and bypass targets.

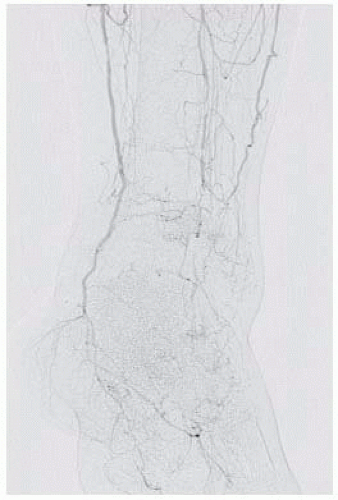

The contralateral femoral artery is accessed and an aortogram with oblique pelvic views is obtained to rule out the presence of inflow disease that may need treatment prior to evaluating the infrainguinal segment. An ipsilateral oblique magnified projection will be helpful in determining if there is any significant common femoral or profunda femoris stenosis, which is especially important if these vessels are to be chosen as the source of inflow for an open bypass (FIG 2).

Deciding on which type of intervention to perform, endovascular versus open, and how aggressive to be about either approach is determined by multiple considerations as outlined earlier and elsewhere in this section. Patients requiring open bypass typically have multilevel disease. As such, it is critically important to image the runoff with the catheter placed proximal to the profunda origin, as the distal runoff will likely be filling from profunda collaterals that are communicating with geniculate collaterals. With common femoral or profunda disease, the catheter will need to be placed in the common iliac artery to evaluate internal iliac collaterals that are in communication with the profunda and more distal collaterals. Performing magnified, time-delayed digital subtraction angiography will assist in revealing which tibial vessels are patent and filling through collateral networks. It is also essential to identify the primary named crural artery that is in continuity to the foot that will perfuse the tissue affected by ischemic ulceration (FIG 3).

FIG 2 • Digital subtraction angiography with catheter placed in the common femoral artery to fill collaterals from the profunda to more distal target vessels.

Using full-strength contrast, magnified projections of the foot will help delineate which pedal vessels are patent, which fill the tarsal and plantar branches, and confirm the status of the plantar arch. Occasionally, there are situations in which no suitable target (e.g., “named” artery) is identifiable and

exploration of a tibial vessel at the time of operative intervention may be required. This exercise is fraught with risk, however, especially in the setting of a desperately ischemic foot, and should rarely be undertaken without conclusive pre- or intraoperative arteriography. Duplex ultrasonography may assist in further defining quality, caliber, and patency of tibial vessels in these situations. Choosing a patent posterior tibialis or anterior tibialis artery in direct continuity with the pedal arteries is preferred over a peroneal artery as a distal target when the former is available, especially in cases of forefoot wounds; however, peroneal arteries are perfectly suitable and serviceable in this situation in the absence of other alternatives.

FIG 3 • Magnified oblique projection of the foot demonstrating a patent plantar arch and digital vessels.

The decision to proceed with open perimalleolar bypass is made in the context of the patient’s overall clinical functional status, cardiopulmonary and renal comorbidities, presence of autogenous saphenous vein conduit, and options for endovascular revascularization. Preoperative autogenous conduit assessment is best performed by detailed ultrasonographic imaging along the length of the vein. Preference is always given to a single segment of greater saphenous vein (GSV) from the ipsilateral leg that is at least 2.5-3 mm in diameter, compressible, and free of thrombus throughout. Assessment of the contralateral GSV is useful in case ipsilateral vein is found to be of poor quality during operative exploration.

Inflow artery selection is usually based on length of available conduit and location of proximal disease. The common, superficial, or deep femoral or popliteal arteries may all serve as suitable inflow arteries in circumstances where minimal or insignificant occlusive disease is present proximally. This determination is best made during diagnostic angiography. The need for concomitant inflow endarterectomy should also be evaluated at this time.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

Type of anesthesia to be used is determined by the type of cardiopulmonary comorbidities and the anatomic level of arterial occlusive disease. Preoperative consultation with anesthesiology and cardiology is customary in this patient population to assess the appropriate amount of surgical risk. General anesthesia, peripheral nerve block, and spinal anesthesia are all potential options in this group of patients. Intraoperative fluid administration should be used judiciously and preoperative preparation should include blood type determination and crossmatching as necessary. It is our practice to hold therapeutic anticoagulation for at least a few days prior to the procedure, but most patients remain on antiplatelet agents through the day of surgery and continue through the perioperative period.

Positioning

Any lower extremity bypass might require intraoperative angiography and, as such, all such procedures should be performed on a radiolucent table. The patient is positioned supine, with the leg slightly abducted and externally rotated to provide optimal exposure of the ipsilateral GSV harvest site (FIG 4). It is our practice to localize the GSV by ultrasound to assist in incision planning. This also helps determine whether the contralateral leg should also be prepped as an alternative site for vein harvesting.

Other items that should be available in the room include a sterile pneumatic tourniquet and surgical bump. Both are useful when the below knee popliteal artery or tibioperoneal trunk is used for arterial inflow for the graft. Open forefoot wounds are excluded from the operative field with adhesive or Ioban drapes.

FIG 4 Positioning of the leg in gentle external rotation to facilitate exposure of the GSV medially. B. Identifying and marking the GSV under ultrasonography. |

TECHNIQUES

PERIMALLEOLAR BYPASS TO THE DISTAL POSTERIOR TIBIALIS ARTERY

First Step: Exposure of the Posterior Tibialis Artery at the Ankle

Simultaneous dissection of the inflow and outflow targets increases the efficiency of the operative approach. The distal incision is marked by palpating posterior to the medial malleolus, taking care to avoid injury to adjacent GSV (FIG 5). Dissection is carried sharply through skin and subcutaneous tissues and through the flexor retinaculum. The tendons of the flexor digitorum longus muscle and flexor hallucis longus pass anteriorly and posteriorly, respectively, to the neurovascular bundle at this level. The paired tibial veins are often seen first as overlying the artery. The tibial nerve travels posterior to the artery and may not be seen clearly during this exposure. The tibial artery does not need to be dissected circumferentially if a pneumatic tourniquet is deployed for proximal control. Use of a tourniquet minimizes risk for venous injury at the dissection site and trauma to the arterial endothelium from vessel loops and vascular clamps. For exposure of the medial and lateral plantar arteries, the same incision is typically carried further distally onto the medial aspect of the foot.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree