Pelvic Exenteration

Cherry E. Koh

Michael J. Solomon

DEFINITION

Pelvic exenteration, also known as extended radical resection, is a form of radical surgery first described for the treatment of locally advanced cervical cancer, which was adopted for locally advanced colorectal cancer shortly thereafter. Currently, locally advanced primary rectal cancers (LARC) and locally recurrent rectal cancers (LRRC) are amongst the more common indications for pelvic exenteration.

The fundamental surgical principle of pelvic exenteration is complete en bloc removal of all viscera or structures contiguously involved by tumor with a clear resection margin (R0 resection). Therefore, depending on the location of the tumor, different types of exenteration will be required, which may include en bloc cystoprostatectomy, vaginectomy, radical hysterectomy, or even sacrectomy. The same surgical principles may be applied to other locally advanced pelvic cancers including uterine, bladder, and prostate cancers and sarcomas.

Different classifications have evolved to describe the different types of recurrence and exenteration, although of note, there is no universally accepted terminology.

Although lengthy anatomical discussion is beyond the scope of this chapter, a brief discussion is necessary to facilitate understanding of the key concepts and principles of surgery.

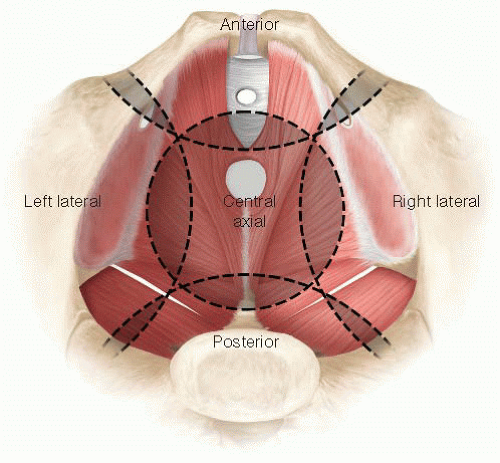

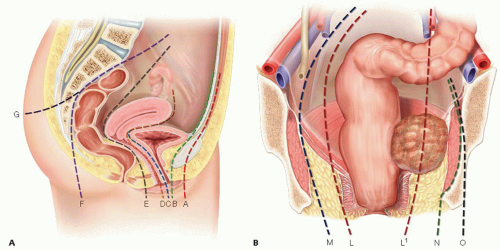

Anatomically, the pelvis can be divided into four compartments: the anterior, central, posterior, and lateral compartments (FIG 1). Each compartment overlaps at their margins but the axis of each compartment is centered on a different structure. The urethra, the tip of the coccyx, the third sacral vertebra, and the ischial spine form the axis of the anterior, central, posterior, and lateral compartments, respectively.

For clarity, exenteration is best classified as complete exenteration or partial exenteration. Complete exenteration is defined as complete removal of all compartments of the pelvis with or without en bloc bony resection, whereas a partial exenteration is defined as the removal of at least three compartments of the pelvis, with or without en bloc bony resection. Within partial exenteration, there are many subtypes of exenterations that often involve surgery on parts of different compartments (FIGS 2A,B).

As a general principle, the resection margin for a compartment will involve excision of the soft tissue at its attachment to the bone or en bloc excision of the involved bone (e.g., en bloc sacrectomy, excision of ischial spine or of pubic ramus). Attempting to obtain a soft tissue margin within a compartment will invariably result in a very rate of highly involved margins. FIGS 2A and 2B illustrate the potential dissection planes depending on the location of the tumor.

In addition to consideration of the compartments of the pelvis, the “height” of the tumor is also important to determine resectability (if there is high sacral involvement), the extent of perineal resection and reconstruction required as well as whether or not intestinal continuity can be restored.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Patients with LARC are usually symptomatic. Patients with LRRC may be symptomatic or asymptomatic (see below), although most patients are symptomatic.

Symptoms experienced by the patient reflect the location of the cancer. Common symptoms include pain, rectal bleeding, altered bowel habits, and tenesmus. Pain may be the result of direct nerve (sacral nerve roots and sciatic nerve), muscle (levator, piriformis, and obturator internus), or bony (sacral) infiltration or the result of referred pain, usually to the buttock or hamstring.

As the tumor gets larger, mass effect may ensue with ureteric or bowel obstruction. Advanced cancers of the pelvis may also present with malignant fistulae between the small or large bowel and an adjacent viscera such as the vagina or bladder. Occasionally, patients may present as an offensive fungating tumor or lymphedema of the lower limb because of venous compression.

Asymptomatic local recurrences may be detected on routine follow-up with elevated carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), surveillance computed tomography (CT), or colonoscopy. Asymptomatic anastomotic recurrence following low rectal

resection may be readily palpable with digital rectal examination or be visible on rigid sigmoidoscopy.

FIG 2 • A. This is the sagittal section of a female pelvis. Planes A and B are the dissection planes for complete or partial exenterations involving the anterior compartment with and without en bloc pubic excision, respectively. Planes C and D are dissection planes for partial exenteration involving the central compartment with total or subtotal vaginectomy and posterior vaginectomy, respectively. Note that planes C and D do not exist in men. Planes E and F are the anterior and posterior total mesorectal excision planes, respectively, whereas plane G is the plane for en bloc sacrectomy. B. Coronal section of the pelvis. There are four possible lateral dissection planes. Plane L represents the total mesorectal excision plane and is the lateral plane for a partial exenteration not involving the lateral compartment. Plane M represents the extravascular plane, which is a plane lateral to the iliac vasculature but medial to obturator internus. Plane N involves excision of the entire lateral compartment including obturator internus, whereas plane O includes en bloc bony resection such as the ischial spine or ischial tuberosity. The right hand side of Figure 2B shows a tumour that involves the lateral compartment. Dissection in the lateral mesorectal plane depicted by plane L1 will invariably result in an involved surgical margin. In order to achieve R0 resection margins, dissection should follow plane N.

As pain frequently accompanies LARC or LRRC, clinical assessment may require an examination under anesthesia, which will also permit biopsies and other investigations to be undertaken concurrently such as a completion colonoscopy or cystoscopy where ureteric stents may also be inserted at the same time if necessary.

In patients with a previous abdominoperineal excision, clinical findings are often limited.

A general assessment for obvious systemic metastasis such as hepatomegaly or inguinal lymphadenopathy should also be performed to rule out the presence of metastatic disease.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

CT scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis is a useful first step to rule out systemic metastasis. In general, CT scans do not provide adequate soft tissue delineation in the pelvis to permit accurate staging of LARC for decision making on neoadjuvant therapy. In patients with potential LRRC, CT scans have are limited in its ability to distinguish between post-surgical fibrosis and tumour recurrence.

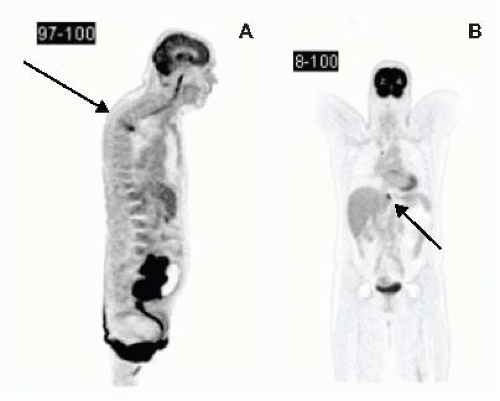

Positron emission tomography (PET) scans complement CT scans in detecting the presence of metastatic disease (FIG 3A,B). By detecting metabolically active tissue, it has the advantage of being able to distinguish between postoperative fibrosis and metabolically active local recurrence. PET in LARC or LRRC has been shown to alter clinical decision making by 20% to 40% by detecting occult metastatic disease.

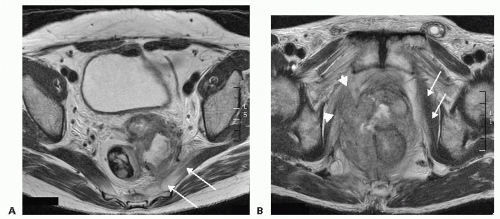

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is currently the gold standard to determine the local extent of tumor, to assess resectability, and to determine the potential need of neoadjuvant (for LARC) therapy (FIG 4A,B). The accuracy of MRI in

confirming anterior compartment, pelvic sidewall and sacral involvement ranges between 60% and 100%. The major limitation of MRI with LRRC resides in its inability to accurately diagnose pelvic sidewall involvement.

Tissue diagnosis, although easily obtained in LARC, is a contentious issue in patients with LRRC when the lesion may be inaccessible luminally and a biopsy would necessitate a percutaneous route that could lead to tract seeding. However, without tissue diagnosis, patients in whom the final pathology report shows no recurrence of cancer may have been subjected to an unnecessary major operation with significant morbidity. It is our practice to accept a diagnosis of LRRC when there is a positive PET scan provided that there is corroborative history, MRI findings, and elevated CEA level.

CEA level is helpful for ongoing disease surveillance in patients with LARC. The sensitivity of CEA for detecting recurrent disease is low but the specificity is 85%.

A complete colonoscopy is performed to obtain tissue diagnosis and to rule out synchronous colon cancer prior to embarking on a major resection.

CT or magnetic resonance angiography may be useful to ensure the patency of inferior epigastric arteries if a rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap is being considered for perineal reconstruction in a patient who previously had or currently has stoma(s). They may also help to determine if a vascular surgeon may be needed if there is major arterial involvement of the common iliac or external iliac vessels.

Cystoscopy can help diagnose bladder involvement and may allow ureteric stenting to relieve ureteric obstruction and prevent impending renal failure.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

All patients should be discussed preoperatively at a multidisciplinary team meeting to determine resectability and operative strategy.

Patients who are radiotherapy naive should be considered for preoperative long-course chemoradiation prior to pelvic exenteration.

A detailed informed consent is obtained. Because studies have shown that patients often underestimate the magnitude of the procedure, we encourage family members to participate in the discussions and we schedule at least two separate consultations.

A preoperative review by the cancer coordinator and psychooncologist is obtained. Further, as most patients will require the creation of at least one, if not two, stoma, it is essential that the patient receive stomal education prior to the procedure.

Bowel preparation is usually necessary for patients without an existing colostomy.

Positioning

Depending on the location and the extent of the cancer, the patient may require surgery from the abdominal and the perineal compartment. In patients where a high sacrectomy is required, repositioning in a prone position after completion of the abdominal and perineal components of the operation is also necessary.

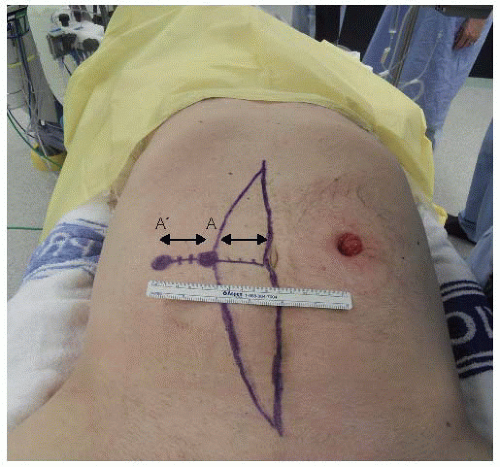

Patients are placed in a modified Lloyd-Davies position directly on a gel mat with both arms tucked by their sides and protecting all pressure areas (FIG 5). In patients who require major perineal resections, the buttocks should be elevated with a rolled towel and overhang the end of the operating bed by up to 5 cm to permit access into the natal cleft if needed.

To avoid muscle compartment syndrome, the legs should not be elevated more than 30 degrees during abdominal phase and only elevated for the perineal phase.

Patients will require an arterial line, a central line, and a large-bore intravenous cannula. These lines need to be well secured prior to be being tucked away by the patient’s sides.

Patients should also receive prophylactic antibiotics, subcutaneous heparin, mechanical venous thromboprophylaxis in the form of graduated compression stockings and calf compressors.

An indwelling Foley catheter is inserted. The anterior thigh is prepped and draped if a vascular graft using the great or common saphenous veins needs to be harvested. The vagina should also be included in the preparation.

A purse-string suture at the anal verge is used to prevent fecal spillage during the procedure.

Prior midline incisions or scars should be marked so that the same incision can be used. In patients where a rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap is planned, this should also be premarked prior to prepping and draping (FIG 5). The colostomy is prepped and covered with a swab, which is then held in place by an impervious adhesive plastic dressing.

Insertion of bilateral ureteric stents is not routinely done in all cases.

TECHNIQUES

ABDOMINAL PHASE

We start with a meticulous adhesiolysis to mobilize all small bowel loops from the pelvis. Avoiding enterotomies in pelvic small bowel loops which may have been damaged by previous radiotherapy is important to prevent a postoperative enterocutaneous fistula.

The abdominal cavity is inspected for peritoneal carcinomatosis or unresectable metastatic liver disease not identified during pre-operative staging. Presence of either usually precludes curative resection and is likely to alter the surgical plan.

Pelvic small bowel loops invaded by cancer should be resected en bloc using linear staplers. The remaining small bowel loops are packed into the upper abdomen using moist sponges held in a fixed table retractor such as the Omni-Tract®.

If the colon is still intact, it should be mobilized along its anatomic planes. Reflection of the sigmoid and descending colon on its mesentery medially will expose the left ureter. Identification of the ureter is important to avoid inadvertent ureteral injury.

For a LARC, a high ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery is performed. The colon is divided at a point of convenience that remains well vascularized. The proximal divided colon can then be packed into the upper abdomen, isolating the pelvis from the abdominal contents.

The appendix is prophylactically removed in patients who require a conduit as dense adhesions and mesh closure of the abdomen would make a future appendectomy difficult.

Lateral Compartment Dissection

There are four possible planes of dissection in the lateral compartment (FIG 2B). Plane L is the conventional total mesorectal excision plane that is familiar to all colorectal surgeons. This plane is used for partial exenterations not involving the lateral compartment or in small anastomotic recurrence that only requires a reoperative anterior resection.

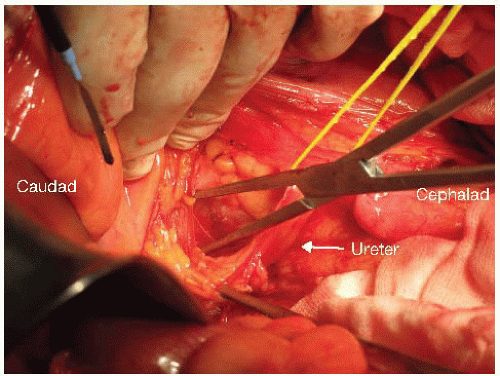

For dissections in plane M, N, or O, the procedure begins with identification and mobilization of the ureters with a cuff of connective tissue to preserve their blood supply (FIG 6). Both ureters are mobilized as distal as possible into the pelvis. If en bloc cystectomy is planned, the ureters are divided without compromising resection margins and to provide adequate ureteric length for urinary reconstruction with an ileal or colonic conduit. Ureters should be anastomosed to the conduit out of the field of prior radiotherapy when possible. Even if en bloc cystectomy is not required, mobilizing the ureters along their entire length allows them to be mobilized off the pelvic sidewall such that the next layer of structures under the ureter (the common, external, and internal iliac arteries) can be accessed (FIG 7).

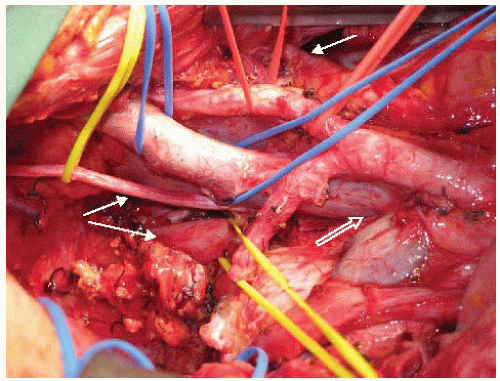

Other than an early anastomotic recurrence, complete pelvic lymphadenectomy, starting at the level of the aortic bifurcation, is routinely performed for most other LRRC. FIG 7 also demonstrates the appearances of the iliac vasculature after complete pelvic lymphadenectomy.

Dissecting in plane M will require ligation and excision of the internal iliac vasculature so as to get into and to

remain in the extravascular plane. Even if formal excision of the internal iliac vasculature is not required, in situ ligation of the internal iliac artery and vein can be helpful to provide vascular control to limit blood loss as the dissection continues, especially if sacrectomy is planned. In LRRC, previous total mesorectal excision and radiotherapy usually cause tissue fibrosis and obliterate tissue planes making dissection difficult. Even if extra-vascular dissection is not necessary, the plane is typically virginal and may be comparatively easier to dissect.

To get into plane M, after ureterolysis is performed, the internal iliac artery is dissected. When an adequate segment of internal iliac artery has been mobilized, it can be suture ligated and divided.

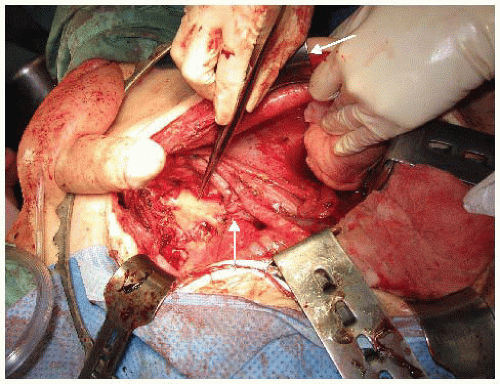

Continued mobilization of the common iliac and external iliac arteries, which do not have any branches within the pelvis, will allow the common and external iliac arteries to be “floated” out of the operative field using two vessel loops held apart to prevent acute kinking of the artery. This exposes the next layer of structures—the common, external, and internal iliac veins. The combination of ligation of the internal iliac venous system and lymphadenectomy will result in progressive exposure of the sacral nerve roots on the piriformis muscle (FIG 8).

FIG 8 • By dissecting and ligating the internal iliacvasculature and performing a lymphadenectomy, the lumbosacral trunks and the sacral plexus (S1, S2, and S3 nerve roots) are displayed. The internal iliac artery and internal iliac vein stumps are seen (arrows). The DeBakey forceps points to the S1 and S2 sacral plexus nerve roots. (S3 has been divided.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access