INTRODUCTION

Health care is not free. Someone must pay. But how? Does each person pay when receiving care? Do people contribute regular amounts in advance so that their care will be paid for when they need it? When a person contributes in advance, might the contribution be used for care given to someone else? If so, who should pay how much?

Health care financing in the United States evolved to its current state through a series of social interventions. Each intervention solved a problem but in turn created its own problems requiring further intervention. This chapter will discuss the historical process of the evolution of health care financing. The enactment in 2010 of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, commonly referred to as the Affordable Care Act, ACA, or “Obamacare,” created major changes in the financing of health care in the United States.

MODES OF PAYING FOR HEALTH CARE

The four basic modes of paying for health care are out-of-pocket payment, individual private insurance, employment-based group private insurance, and government financing (Table 2-1). These four modes can be viewed both as a historical progression and as a categorization of current health care financing.

| Type of Payment | Percentage of National Health Expenditures, 2013 |

| Out-of-pocket payment | 12% |

| Individual private insurance | 3% |

| Employment-based private insurance | 30%b |

| Government financing | 47% |

| Other | 8% |

| Total | 100% |

| Principal source of coverage | Percentage of population, 2013 |

| Uninsured | 13% |

| Individual private insurance | 7% |

| Employment-based private insurance | 47% |

| Government financing | 33% |

| Total | 100% |

Fred Farmer broke his leg in 1913. His son ran 4 miles to get the doctor, who came to the farm to splint the leg. Fred gave the doctor a couple of chickens to pay for the visit. His great-grandson, Ted, who is uninsured, broke his leg in 2013. He was driven to the emergency room, where the physician ordered an x-ray and called in an orthopedist who placed a cast on the leg. The cost was $2,800.

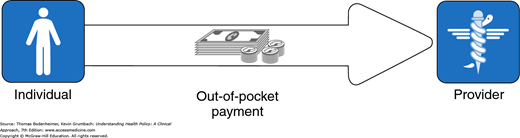

One hundred years ago, people like Fred Farmer paid physicians and other health care practitioners in cash or through barter. In the first half of the twentieth century, out-of-pocket cash payment was the most common method of payment. This is the simplest mode of financing—direct purchase by the consumer of goods and services (Fig. 2-1).

People in the United States purchase most consumer items and services, from gourmet restaurant dinners to haircuts, through direct out-of-pocket payments. This is not the case with health care (Arrow, 1963; Evans, 1984), and one may ask why health care is not considered a typical consumer item.

Whereas a gourmet dinner is a luxury, health care is regarded as a basic human need by most people.

For 2 weeks, Marina Perez has had vaginal bleeding and has felt dizzy. She has no insurance and is terrified that medical care might eat up her $500 in savings. She scrapes together $100 to see her doctor, who finds that her blood pressure falls to 90/50 mm Hg upon standing and that her hematocrit is 26%. The doctor calls Marina’s sister Juanita to drive her to the hospital. Marina gets into the car and tells Juanita to take her home.

If health care is a basic human right, then people who are unable to afford health care must have a payment mechanism available that is not reliant on out-of-pocket payments.

Whereas the purchase of a gourmet meal is a matter of choice and the price is shown to the buyer, the need for and cost of health care services are unpredictable. Most people do not know if or when they may become severely ill or injured or what the cost of care will be.

Jake has a headache and visits the doctor, but he does not know whether the headache will cost $100 for a physician visit plus the price of a bottle of ibuprofen, $1,200 for an MRI, or $200,000 for surgery and irradiation for brain cancer.

The unpredictability of many health care needs makes it difficult to plan for these expenses. The medical costs associated with serious illness or injury usually exceed a middle-class family’s savings.

Unlike the purchaser of a gourmet meal, a person in need of health care may have little knowledge of what he or she is buying at the time when care is needed.

Jenny develops acute abdominal pain and goes to the hospital to purchase a remedy for her pain. The physician tells her that she has acute cholecystitis or a perforated ulcer and recommends hospitalization, an abdominal CT scan, and upper endoscopic studies. Will Jenny, lying on a gurney in the emergency room and clutching her abdomen with one hand, use her other hand to leaf through a textbook of internal medicine to determine whether she really needs these services, and should she have brought along a copy of Consumer Reports to learn where to purchase them at the cheapest price?

Health care is the foremost example of asymmetry of information between providers and consumers (Evans, 1984). A patient with abdominal pain is in a poor position to question a physician who is ordering laboratory tests, x-rays, or surgery. When health care is elective, patients can weigh the pros and cons of different treatment options, but even so, recommendations may be filtered through the biases of the physician providing the information. Compared with the voluntary demand for gourmet meals, the demand for health services is partially involuntary and is often physician rather than consumer-driven.

For these reasons among others, out-of-pocket payments are flawed as a dominant method of paying for health care services. Because the direct purchase of health services became increasingly difficult for consumers and was not meeting the needs of hospitals and physicians to be reliably paid, health insurance came into being.

In 2012, Bud Carpenter was self-employed. To pay the $500 monthly premium for his individual health insurance policy, he had to work extra jobs on weekends, and the $5,000 deductible meant he would still have to pay quite a bit of his family’s medical costs out of pocket. Mr. Carpenter preferred to pay these costs rather than take the risk of spending the money saved for his children’s college education on a major illness. When he became ill with leukemia and the hospital bill reached $80,000, Mr. Carpenter appreciated the value of health insurance. Nonetheless he had to feel disgruntled when he read a newspaper story listing his insurance company among those that paid out on average less than 60 cents for health services for every dollar collected in premiums.

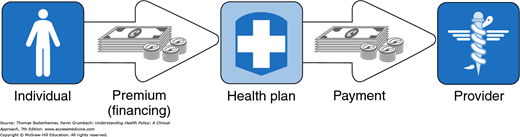

With private health insurance, a third party, the insurer is added to the patient and the health care provider, who are the two basic parties of the health care transaction. While the out-of-pocket mode of payment is limited to a single financial transaction, private insurance requires two transactions—a premium payment from the individual to an insurance plan (also called a health plan), and a payment from the insurance plan to the provider (Fig. 2-2). In nineteenth-century Europe, voluntary benefit funds were set up by guilds, industries, and mutual societies. In return for paying a monthly sum, people received assistance in case of illness. This early form of private health insurance was slow to develop in the United States. In the early twentieth century, European immigrants set up some small benevolent societies in US cities to provide sickness benefits for their members. During the same period, two commercial insurance companies, Metropolitan Life and Prudential, collected 10 to 25 cents per week from workers for life insurance policies that also paid for funerals and the expenses of a final illness. The policies were paid for by individuals on a weekly basis, so large numbers of insurance agents had to visit their clients to collect the premiums as soon after payday as possible. Because of the huge administrative costs, individual health insurance never became a dominant method of paying for health care (Starr, 1982). In 2013, prior to the implementation of the individual insurance mandate of the ACA, individual policies provided health insurance for 7% of the US population (Table 2–1).

Figure 2-2

Individual private insurance. A third party, the insurance plan (health plan), is added, dividing payment into a financing component and a payment component. The ACA added an individual coverage mandate for those not otherwise insured and federal subsidy to help individuals pay the insurance premium.

In 2014, Bud Carpenter signed up for individual insurance for his family of 4 through Covered California, the state exchange set up under the ACA. Because his family income was 200% of the federal poverty level, he received a subsidy of $1,373 per month, meaning that his premium would be $252 per month (down from his previous monthly premium of $500) for a silver plan with Kaiser Permanente. His deductible was $2,000 (down from $5,000). Insurance companies were no longer allowed to deny coverage for his pre-existing leukemia.

The ACA has many provisions, described in detail in the Kaiser Family Foundation (2013a) Summary of the Affordable Care Act and discussed more in Chapter 15. One of the main provisions is a requirement (called the “individual mandate”) that most US citizens and legal residents who do not have governmental or private health insurance purchase a private health insurance policy through a federal or state health insurance exchange, with federal subsidies for individual and families with incomes between 100% and 400% of the federal poverty level ($24,250 to $97,000 for a family of four). Details of the individual mandate are provided in Table 2-2.

| U.S. citizens and legal residents are required to have health coverage with exemptions available for such issues as financial hardship. Those who choose to go without coverage pay a tax penalty of $325 or 2% of taxable income in 2015, which gradually increases over the years. People with employer-based and governmental health insurance are not required to purchase the insurance required under the individual mandate. |

| Tax credits to help pay health insurance premiums increase in size as family incomes rise from 100% to 400% of the Federal Poverty Level. In addition subsidies reduce the amount of out-of-pocket costs individuals and families must pay; the amount of the subsidy varies by income. |

| Under the individual mandate, health insurance is purchased though insurance marketplaces called health insurance exchanges. Seventeen states have elected to set up their own exchanges; the remainder of states are covered by the federal exchange, Healthcare.gov. |

Insurance companies marketing their plans through the exchanges offer four benefit categories:

|

| Most people who have obtained insurance through the exchanges have picked Bronze or Silver plans, and 87% have received a subsidy. A family of four with income at 150% of the federal poverty level receives an average subsidy of $11,000. At 300% of the federal poverty level the subsidy is about $6,000. |

Betty Lerner and her schoolteacher colleagues each paid $6 per year to Prepaid Hospital in 1929. Ms. Lerner suffered a heart attack and was hospitalized at no cost. The following year Prepaid Hospital built a new wing and raised the teachers’ prepayment to $12.

Rose Riveter retired in 1961. Her health insurance premium for hospital and physician care, formerly paid by her employer, had been $25 per month. When she called the insurance company to obtain individual coverage, she was told that premiums at age 65 cost $70 per month. She could not afford the insurance and wondered what would happen if she became ill.

The development of private health insurance in the United States was impelled by the increasing effectiveness and rising costs of hospital care. Hospitals became places not only in which to die, but also in which to get well. However, many patients were unable to pay for hospital care, and this meant that hospitals were unable to attract “customers.”

In 1929, Baylor University Hospital agreed to provide up to 21 days of hospital care to 1,500 Dallas schoolteachers such as Betty Lerner if they paid the hospital $6 per person per year. As the Great Depression deepened and private hospital occupancy in 1931 fell to 62%, similar hospital-centered private insurance plans spread. These plans (anticipating health maintenance organizations [HMOs]) restricted care to a particular hospital. The American Hospital Association built on this prepayment movement and established statewide Blue Cross hospital insurance plans allowing free choice of hospital. By 1940, 39 Blue Cross plans controlled by the private hospital industry had enrolled over 6 million people. The Great Depression reduced the amount patients could pay physicians out of pocket, and in 1939, the California Medical Association set up the first Blue Shield plan to cover physician services. These plans, controlled by state medical societies, followed Blue Cross in spreading across the nation (Starr, 1982; Fein, 1986).

In contrast to the consumer-driven development of health insurance in European nations, coverage in the United States was initiated by health care providers seeking a steady source of income. Hospital and physician control over the “Blues,” a major sector of the health insurance industry, guaranteed that payment would be generous and that cost control would remain on the back burner (Law, 1974; Starr, 1982).

The rapid growth of employment-based private insurance was spurred by an accident of history. During World War II, wage and price controls prevented companies from granting wage increases, but allowed the growth of fringe benefits. With a labor shortage, companies competing for workers began to offer health insurance to employees such as Rose Riveter as a fringe benefit. After the war, unions picked up on this trend and negotiated for health benefits. The results were dramatic: Enrollment in group hospital insurance plans grew from 12 million in 1940 to 142 million in 1988.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree