Patent Activities and Issues

Pricing is a major microeconomic factor at the time of [patent] expiry: the patent holder has the option of joining the fight with a price drop, he can leave it where it is and bank on smaller volume and a good continuing margin, or he can drop it selectively to large volume areas of sale.

–Steve Kiss. From MM&M (November 1976).

Ingenuity should receive a liberal encouragement.

–Thomas Jefferson

Congress intended statutory subject matter to include anything under the sun made by man.

–Chief Justice Warren Burger, majority opinion, Diamond v. Chakrabarty.

Intellectual property laws seek to protect creative discoveries of inventions and thinking. Intellectual property law includes not only patents, but also trademarks, designs, trade secrets, and copyrights. An important goal of these laws is to encourage people to invest in research and development. This chapter focuses on patents.

WHAT IS A PATENT?

A patent is a legal document that grants the patentee a potential right of exclusion to a claimed invention. Patents provide a written description of the invention and, in the United States, the manner in which one can make and use it. Patents are defined by a series of claims that serve to set forth the boundaries of what is considered the invention. Patents, by definition, describe the invention through embodiments that do not obscure the invention. A patent may be considered to be a contract between the government and the inventor, giving the inventor the right to control the property for a set number of years in return for a full and complete disclosure of the invention.

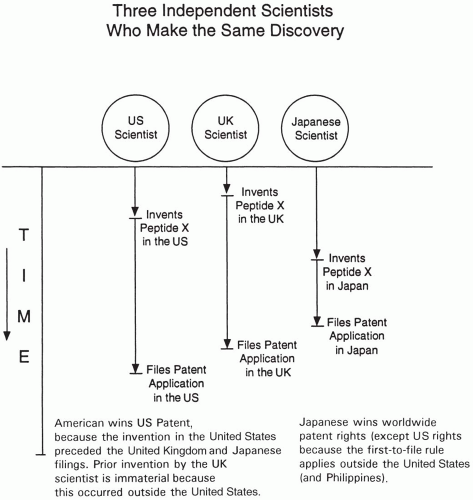

In most countries, a patent is granted to the first person to file a patent application that satisfies the criteria for obtaining a patent (the so-called “first-to-file” system). In the United States, a patent is granted to the first person to conceive of the invention and diligently reduce an invention to practice, even in circumstances where the individual was not the first to file the patent application (the so-called “first-to-invent” system). A bill passed by the US House of Representatives in September 2007 (the Patent Reform Act) proposes to convert the United States from a “first to invent” to a “first-to-file” system.

The right of exclusion conferred by a patent is for a specified period of time, during which anyone who manufactures, uses, imports, or sells the patented invention may be fined and/or prevented from such practice by an order of a court. This right of exclusion is predicated upon the patent being valid, in that it satisfies all statutory requirements of having a real-world utility, being novel and unobvious in view of any patent, patent application, or printed publication prior to the effective filing date of the patent application. The application must set forth a complete description of the invention, one that enables one “skilled in the art” to make and use the invention and one of sufficient detail that the skilled artisan would accept that the patentee was in possession of the claimed invention.

Patents provide jurisdictional protection, in that the invention only has protection in the jurisdictions in which a valid patent has been issued. Patents are property, such that one may sell or assign rights to his/her patent to a third party, who in turn may exercise his rights in the invention.

A patent application is submitted to a regional patent office or to a specific country in which patent protection is sought. One may file a Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) International Application, which allows the applicant to delay submitting an application to one or more specific regions or countries for a given time. Regardless of the route of filing a patent application, patents are issued on a country-by-country basis, most commonly after an extensive examination process by that country’s patent office.

Types of Patents

From a pharmaceutical perspective, there are a few different types of patents.

Composition of matter patents. These are the strongest patents because they include all uses of the material (i.e., compound, drug, biological, diagnostic).

Use patents. These cover a specific use of a compound, drug, or biological, presumably to treat or prevent a disease. These are strong patents in most developed countries. However, in some countries, novel uses of a known compound, drug, or biological are not patentable, or if they are, the patents are not as strong as in developed countries. This difference exists because of weaker enforcement laws in those countries.

Process or manufacturing patents. These cover the process or method of manufacture of the compound, drug, or biological and are sometimes important in helping to protect a drug that is going off-patent in terms of a composition of matter or use patent, particularly when a new more efficient method of manufacture has been invented that allows the product to be made for a lower price. These patents do not prevent another company from manufacturing the off-patent drug or biological using a different manufacturing method.

Formulation patent. These cover newer formulations of a known drug and often are granted for sustained-release formulations or new salts of the drug with unexpected properties. These patents do not protect the original drug or extend the original patent life, but if the new formulation has medical advantages in comparison with the original, then this type of patent is likely to be highly important to the company.

Patents versus Trade Secrets

Patents are by their nature a quid pro quo, in that the patentee provides full disclosure of the invention in return for a protected period of exclusion of others from practicing the invention. Another means of obtaining intellectual property protection, however, is the so called “trade secret,” where an invention (e.g., a consumer product formula like Coca-Cola) is maintained under

the highest level of secrecy, such that only someone with direct access to information by the inventor would know the details of the invention. Such demonstration of preserved and diligent maintenance of secrecy has validity in the eyes of courts, and individuals found divulging trade secrets are liable for damages that result.

the highest level of secrecy, such that only someone with direct access to information by the inventor would know the details of the invention. Such demonstration of preserved and diligent maintenance of secrecy has validity in the eyes of courts, and individuals found divulging trade secrets are liable for damages that result.

Trade secrets are thus antithetical to patents because they maintain the details of an invention secret, such that the skilled artisan is unable to make and use the invention at hand, without further guidance.

Protection afforded by a trade secret may last as long as the secret is maintained and thus provides a longer term than a patent for such an invention. However, there are a number of significant drawbacks to reliance upon a trade secret, including the challenge in maintaining the trade secret and the fact that successful reverse engineering of an invention usually precludes the invention from being kept as a trade secret. For example, assume that a company has a “secret formula” for its flavored water soft drink. A competitor has successfully arrived at an essentially identical drink through trial-and-error experimentation in its laboratory. The competitor thus did not violate the company’s trade secret and cannot be sanctioned as a result.

WHAT CAN BE PATENTED?

Patents may be obtained for any invention with a credible and “real-world utility.” Thus, an idea or concept is not patentable per se, but a tangible method, material substance, item, process, or device based upon the idea or concept may be patented. Patents may be obtained for man-made processes and materials; thus, materials found in nature or natural processes occurring in a biological subject cannot be patented.

Patents are the cornerstone of protection for inventions in the biotechnology and pharmaceutical industries. Patent protection is routinely sought for newly developed compounds, new uses of known compounds, formulations for delivery of the compound, and improved processes to obtain the compound. Another emerging area of interest is the isolation and/or modification of natural products that have therapeutic utility. In some instances, such products are modified and thus may be patented. In other instances, high-yield methods for natural products are developed (e.g., products available in only limited supply). The statutes specifically list “process, machine, manufacture or composition of matter.”

Therefore, for drugs, it is possible to patent:

An active compound or substance itself (i.e., a compound patent)

A new medical use of an unpatented or off-patent (i.e., known) drug or a patented drug (i.e., a use patent)

A pharmaceutical formulation of a compound (i.e., a formulation patent)

A new or improved process to make a drug (i.e., a process patent)

New isomers, hydrates, or crystalline forms of the drug that have unexpected advantageous properties

In addition, patented materials must be novel and unobvious in terms of what has been previously known to the public. Thus products, devices, and methods that have been described in a patent, patent application, printed publication, public conference, or meeting or advertised or sold prior to the filing date of the patent application are not patentable. These criteria apply regardless of the source of the public disclosure. An inventor publicizing his invention prior to the filing of a patent application (e.g., by comments at a public meeting) compromises his ability to obtain a patent to the invention.

DURATION OF A PATENT

The term of an issued patent is 20 years from the effective filing date of the application. In some instances, a patent application may be related to a prior filed application and, therefore, claim an effective filing date of the prior application. Thus, its term would be 20 years from the filing date of the prior filed application. This term is subject to the payment of periodic maintenance fees, which vary in timing based on the jurisdiction.

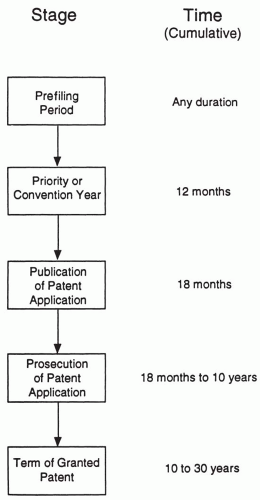

The “birth” and life of a patent may be viewed as consisting of five stages. These are schematically shown in Fig. 109.1. There is little or no overlap between these stages, although the duration of each stage may be very variable.

PROCEDURES FOR OBTAINING A PATENT

While certain aspects of patents vary, depending upon the jurisdiction in which the application is filed, contracting states (i.e., countries) of the PCT have some uniformity in terms of what is required to obtain a patent. A patent application must provide a background or context for the invention, a summary of the invention, and a description of the invention that enables one skilled in the art to make and use the invention and must support the notion that the inventor was in possession of the claimed invention. Patents are defined by their claims, which alert the public to the boundaries of what is to be considered the invention.

Currently, most biotechnology companies use the PCT application initially. This enables a company to apply in allterritories (about 117 countries), which is converted to national patents 30 months after the original filing. See the World Intellectual Property Organization in the Additional Readings section at the end of this chapter for addresses and websites. About 18 months after filing with the PCT, the applicant can identify the specific countries in which he or she wishes to file.

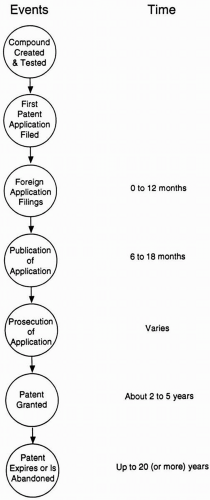

Different jurisdictions have different requirements for such claims. For example, in the United States, it is permissible to claim a method of treatment of a human subject, whereas in European countries, a method of treatment claim is not permissible. Instead, claims phrased as use of a compound to prepare a medicament for the treatment of the disease are permissible. In India, however, even those claims are not permissible. While most countries around the world allow for claims to materials, compositions, and devices, the ability to patent methods for using them or other method type claims varies greatly by jurisdiction. Table 109.1 summarizes elements of patent applications common to most jurisdictions. Figure 109.2 describes the process, protocol, and timing of filing applications.

Where and When to File a Patent

Often a patent strategy involves the filing of a single application in a single jurisdiction as a means of reducing associated costs at an early stage of product development. This initial filing is usually in a country that is a contracting country of the PCT, and within one year from the initial filing date, an International PCT Application must be filed that claims priority to the initial regional application. The initial regional application preserves a date for defensive purposes, while the term of the patent is regarded to be up to 20 years from the PCT filing date. This approach earns the applicant an additional year of patent protection

without compromising that year for the term of the patent. The initial regional application is subject to the patentability standards of the region in which it was filed. For example, if the initial regional application is filed in Great Britain, it will comprise all elements of a British application, including a full set of claims that are novel and unobvious in view of the art, and contain industrial applicability and a specification that satisfies written description requirements. The initial regional application can mature into an issued patent if it satisfies the requirements of the patent office in that country.

without compromising that year for the term of the patent. The initial regional application is subject to the patentability standards of the region in which it was filed. For example, if the initial regional application is filed in Great Britain, it will comprise all elements of a British application, including a full set of claims that are novel and unobvious in view of the art, and contain industrial applicability and a specification that satisfies written description requirements. The initial regional application can mature into an issued patent if it satisfies the requirements of the patent office in that country.

Table 109.1 Contents of a patent application | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||

Figure 109.2 Series of major events in the patenting of a new compound. The middle stage (“publication of an application”) is not applicable in the United States. |

Another practice undertaken is the filing of a provisional patent application in the United States. For a nominal filing fee, the provisional patent application also enables the inventor to secure a priority filing date for defensive purposes, yet does not compromise patent term. On the one-year anniversary of the provisional application, however, provisional patent applications expire. Provisional applications do not automatically mature into issued patents; rather, a utility application must be filed on or before the one-year anniversary of the provisional filing date, claiming the benefit of the provisional application.

In most jurisdictions, an application may claim priority of a prior filed application or applications, so long as not more than one year has passed since the effective filing date of the prior application.

In the United States, however, an application may claim priority of a prior filed application or applications for the duration while the prior application is pending. Such applications may be “continuation” applications, where there is no additional material incorporated in the latter filed application as compared to the prior application. However, a different aspect of the invention is claimed in the latter application, for example. Another means of continued prosecution in the United States is the filing of a “continuationin-part” application, where some additional material may be incorporated in the application; however, the scope of the claims are fully supported in the prior application. The number of such continuing applications that may be filed was limitless in the past; however, recently (August 21, 2007), the US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) published a final series of rule changes, which significantly limits this practice. The changes to the rules went into effect on November 1, 2007.

What Does a Patent Look Like?

The parts and form of a patent are relatively comparable in different jurisdictions. A patent will have a background section, describing the state of the art in the field of the invention. Following the background section is a brief summary of the invention and a brief description of any drawings that are referred to in the invention. A detailed description is then provided, setting forth embodiments of the invention and providing sufficient detail for one skilled in the art to know how to make and use the invention, as well as supporting the notion that the applicant was in possession of the claimed invention at the time the invention was made. Some applications have figures, which are referred to in the description of the invention, and/or examples of embodiments of the invention. Patents will conclude with a listing of claims that set forth the boundaries of the invention. Claims are numbered in succession, beginning with an independent claim, which does not refer to any other claims and addresses the broadest scope for the matter being claimed. This is followed typically by dependent claims, which are narrower in scope than the independent claim and also refer to other claims. In general, patent claims start with broad claims and then list progressively narrower ones. An abstract of the invention is also provided, which describes the essence of the invention and the field to which the invention applies.

BASIS OF ISSUING A PATENT

Criteria for Awarding Patents

Following submission of a patent application, the receiving patent office will, in general, publish the application and initiate examination of the application. The initial examination entails consideration of whether the claims are directed to a single unified invention or have to be divided into two or more separate patent applications. A search of publications, patents, and patent applications follows to ascertain whether the invention is both novel and nonobvious and also has utility (i.e., practical application). The examiner will then issue a communication, commonly referred to as an “Office Action,” in which he advises the inventor about the status of the application in view of the examination procedure he has conducted.

It is typical for the claims to be rejected on the initial review. This initial rejection is often based on one or more of the following reasons:

The applicant is making claims that are broader than the supporting evidence.

The invention is obvious.

The invention does not work.

The invention is already known.

The applicant or his representative then submits a response, where any allegations that the invention is not patentable are rebutted. Often, this response is accompanied by an amendment of one or more claims, for example, to further clarify points of contention. It is not unusual to have several such back-and-forth communications between a patent examiner and an inventor (or his representative). Following such correspondence, if the examiner agrees that the claims and application satisfy established patent requirements, then the examiner notifies the applicant that the claims are allowable, and prosecution is closed. The application then issues as a granted patent, upon payment of the appropriate fees.

Prior User Rights

Many countries outside the United States have “prior user” rights that allow an earlier inventor to continue practicing an invention later patented by another, although the prior user cannot contest the validity of the patent as they may do in the United States.

First to File versus First to Invent

The concepts of first to file and first to invent are at the heart of many patent problems where more than one person or group claims to have made the invention or discovery. Nearly all countries of the world, except for the United States and Philippines, can be characterized as first-to-file countries. This means that the person or group who files first in a member country’s patent office is awarded a patent regardless of who actually invented first. This issue is schematically shown in Fig. 109.3, where two different people could each obtain a patent for the same invention. In the United States, if one can demonstrate through laboratory

notebooks or other means that he invented a compound before someone else who has filed a patent application first, then the person who invented the compound first will be granted the patent.

notebooks or other means that he invented a compound before someone else who has filed a patent application first, then the person who invented the compound first will be granted the patent.

Patents Granted without Data

Patent applications are sometimes filed based on a theory or hypothesis, even if no actual data have been obtained. This is called a constructive reduction to practice. If the basic criteria are met and the patent examiner does not require proof [e.g., that the novel compound(s) has the medical uses claimed], a patent may be granted. This is more likely to occur if the compound to be patented is a derivative of a known patented compound with a theoretical advantage. For example, a chiral form of a molecule may be hypothesized to have a theoretical advantage, and a patent may be obtained without actually demonstrating an advantage. Another example might be a segment of a known polymer that may be hypothesized to have advantages over the higher molecular weight parent polymer. In most cases, however, the patent examiner will require proof of new and unexpected properties to grant a patent for a variant of a known compound.

The standard by which a patent application is judged is whether it is able to be understood by “one of ordinary skill in the art.” An application has sufficient description if one skilled in the art would accept that the description provided in a given application is sufficient. The filing of a patent application is considered to be a reduction of an invention to practice because it provides a description regarding how to make and use the invention. While working models of a given invention may be highly illustrative, clearly one skilled in the art does not necessarily need such a model to comprehend and be able to make

and use an invention, in particular if the level of skill in the art is sufficiently high and the methods, materials, etc., used to obtain the invention are standard.

and use an invention, in particular if the level of skill in the art is sufficiently high and the methods, materials, etc., used to obtain the invention are standard.

For example, assume that a specific device (e.g., a camera) is known by those skilled in the art to produce images of luminescent compounds given to humans as part of their treatment. Also assume that a new compound is identified that is highly luminescent and may be used as an imaging agent. Further assume that a new lens is created that eliminates much out-of-plane luminescence of this compound in benchtop models. One skilled in the art would likely accept that the level of skill in the art is sufficiently high, that incorporation of the lens in the device may be readily accomplished, and that a patent may be obtained on the lens. Thus, even in the absence of the inventor having proven successful incorporation of the lens into the complex device, claims about the lens should be patentable.

It has been stated (primarily in jest) that many basic scientists have switched their approach to conducting research because of the biotechnology revolution. In the years prior to 1975, a scientist would form a hypothesis, design experiments, collect data, and then apply for a patent. Since that time, it seems that scientists working in biotechnology first formulate a hypothesis, then apply for a patent, and lastly raise $15 to $20 million to conduct the experiments to test the hypothesis.

Invention Cascade

Companies do not want to rely on a single patent for protection of their huge financial investment in a potential or actual marketed product. In addition, they will continue discovery activities using a specific technology or studying a specific class or series of chemicals seeking improved compounds that can become second-generation drugs.

A company seldom files a single patent application in isolation; usually there is a series of applications. Within 18 months after global filings on invention A, there is publication of the patent application (e.g., the US or European patent application). If the research on invention A has progressed and a company wishes to file on invention B, the company should file before the publication occurs. If it does not file within this time, then the prior art established by the publication of the patent application on invention A may well make invention B unpatentable. Before the publication of the patent application on invention B, a company may file on invention C, and so forth. This is referred to as an invention cascade.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree