Pancreaticoduodenectomy: Resection

George VanBuren II

William E. Fisher

DEFINITION

Pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple procedure) is defined as resection of the pancreatic head, uncinate process, gallbladder, distal bile duct, duodenum, and gastric antrum.

Pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy (pyloruspreserving Whipple procedure) is the same operation with preservation of the gastric antrum, pylorus, and a cuff of proximal duodenum.

Complete excision of pancreatic head tumors with negative margins maximizes local-regional control and is the standard of care for malignancies of the pancreatic head, ampulla of Vater, duodenum, or distal bile duct.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor

Pancreatic cystic neoplasm

Cancer of the ampulla of Vater

Distal cholangiocarcinoma

Duodenal adenocarcinoma

Biliary stricture

Chronic pancreatitis

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

A thorough history and physical exam should be performed prior to treatment.

Critical history: weight loss greater than 10%, new-onset diabetes, jaundice, vague abdominal pain in mid-epigastrium, pain penetrating to the back (indicates possible celiac involvement), diarrhea (indicating exocrine insufficiency)

History related to biliary obstruction: jaundice, fever, chills, pruritus, acholic stools, dark urine

Risk factors for pancreatic cancer: smoking, chronic pancreatitis, diabetes, age 65 years or older, African American race, obesity, male gender, family history of pancreatic cancer, family history of other malignancy (i.e., BRCA2 malignancies)1

Physical exam: scleral icterus, jaundice, signs of malnutrition, cachexia, temporal wasting

Ominous signs: A palpable abdominal tumor or ascites may indicate metastatic disease. Left supraclavicular lymphadenopathy (Virchow’s lymph node) is indicative of metastatic disease.

In addition to a history and physical relating to pancreatic cancer, an overall assessment of the patient’s functional status should be performed to assure the patient is a candidate for major surgery.

If the patient’s performance status is poor (Eastern Conference Oncology Group [ECOG] score greater than 2 or Karnofsky score of less than 60), he or she should be considered physiologically borderline resectable.2

The patient’s cardiopulmonary status should also be assessed with an assessment of their exercise tolerance and activity level.

Physical exam should look for other sources of chronic disease including carotid bruit, jugular venous distension, rales, wheezing, heart murmur, or clubbing of fingers.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

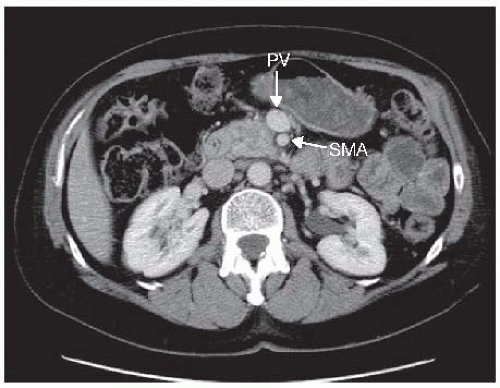

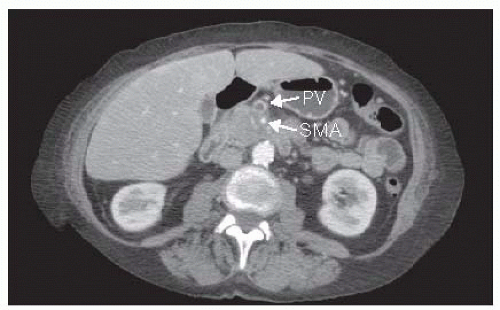

“Pancreatic protocol” computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis is required for all patients. Pancreatic protocol is a triphasic thin (≤5 mm), multislice CT scan with an arterial, venous, and delayed phase in conjunction with sagittal and coronal views. Water is used to opacify the stomach. A properly performed CT scan is perhaps the most critical portion of the preoperative assessment to determine if the patient is a candidate for surgery. The purpose of the CT scan is to detect any metastatic disease and to assess the relationship of the low-density tumor to the surrounding vasculature. Particular attention is paid to the relationship of the tumor to the portal vein (PV), superior mesenteric vein (SMV), superior mesenteric artery (SMA), hepatic artery, and celiac axis. In addition, a CT will aid in identification of aberrant anatomy of the hepatic artery, which is present in 20% of cases and must be noted prior to surgery.

CT scan of chest is done to evaluate for pulmonary metastasis.

Based on imaging, there are well-defined consensus criteria from the American Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Association for resectable, borderline resectable, locally advanced, and metastatic diseases. These criteria have been adopted by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN).3

Resectable tumors demonstrate the following:

No distant metastases; no radiographic evidence of SMV and PV abutment, distortion, tumor thrombus, or venous encasement; clear fat planes around the celiac axis, hepatic artery, and SMA (FIG 1)

Borderline resectable tumors demonstrate the following:

No distant metastases; venous involvement of the SMV/PV demonstrating tumor abutment with or without impingement and narrowing of the lumen, encasement of the SMV/PV but without encasement of the nearby arteries, or short segment venous occlusion resulting from either tumor thrombus or encasement but with suitable vessel proximal and distal to the area of vessel involvement, allowing for safe resection and reconstruction; gastroduodenal artery (GDA) encasement up to the hepatic artery with either short segment encasement or direct abutment of the hepatic artery, without extension to the celiac axis; tumor abutment of the SMA not to exceed 180 degrees of the circumference of the vessel wall (FIG 2)

Locally advanced tumors demonstrate the following:

No distant metastases; unreconstructable SMV/PV occlusion; greater than 180 degree encasement of SMA, celiac axis, or aortic invasion; metastasis to lymph nodes beyond the field of resection (FIG 3)

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS). This is an important step in the assessment of many, but not all, pancreatic masses and cystic lesions. EUS is performed to obtain a tissue diagnosis of a solid mass, which will be required if neoadjuvant chemotherapy is planned. Cystic lesions may be characterized by EUS and the fluid may be aspirated and sent for cytology including a mucin stain, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and amylase concentration, and perhaps, genetic analysis. Furthermore, EUS may be used as an adjunct to the CT scan to further evaluate venous involvement and can be more sensitive than CT in detecting a small mass. If enlarged celiac lymph nodes are seen, they may be biopsied. EUS and CT can be compromised by the presence of a bile duct stent so ideally, these tests are performed prior to endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

FIG 3 • CT of an unresectable/locally advanced pancreatic cancer. The lesion has encircled the SMA. PV, portal vein.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). ERCP may be used to provide biliary decompression. In cholangiocarcinomas, it is necessary to evaluate the entirety of the biliary tree and see the proximal extent of the stricture. This may require a percutaneous transhepatic cholangiogram. In ampullary carcinomas, the mass can be directly visualized and biopsied. A biliary stent should be placed if neoadjuvant therapy is planned, to allow time for referral to a high-volume pancreas surgery center, and in cases where the serum bilirubin is particularly elevated (>10 mg/dL).4 Although stent placement has been shown to increase infectious complications, prolonged biliary obstruction causing liver insufficiency and coagulopathy adversely affects surgical outcomes.

Duplex ultrasound of the neck is performed selectively in patients who may need to undergo PV resection to evaluate the patency of the internal jugular veins. It may also evaluate the carotids in patients at high risk for atherosclerotic disease.

Octreotide scan. Octreotide scan is a radionuclide scan used for localization of primary and metastatic neuroendocrine tumors. Radioactive octreotide attaches to tumor cells that have receptors for somatostatin. Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy and three-dimensional single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) images are taken at 4 hours and 24 hours. The tracer is visible in the thyroid, liver, gallbladder, kidneys, spleen, and urinary bladder; the physiologic uptake by these organs is diffuse. Carcinoid tumors may be seen at 24 hours more clearly than at 4 hours by virtue of reduction in background activity.

Tumor markers. Serum carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA 19-9) is shown to be predictive of outcomes in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. However, CA 19-9 can be falsely elevated in the setting of obstructive jaundice. If it is more than 1,000 U/mL in the absence of jaundice, there should be a high suspicion for metastatic disease.5 In patients who receive neoadjuvant therapy, CA 19-9 may be used as a marker to assess response. A drop in CA 19-9 of greater than 50% may be predictive of improved survival.2 A low value is not predictive of favorable biology. Serum chromogranin A should be performed in patients with pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Elevated chromogranin A may be followed as a marker; a low value is not predictive of favorable biology.

Liver function test and coagulation profile: Bile salts are required for absorption of vitamins A, D, E, and K. Patients with biliary obstruction may require vitamin K (10 mg administered intramuscularly three times every day) if the prothrombin time/international normalized ratio (PT/INR) is prolonged. A serum albumin level of less than 3 may indicate the need for preoperative nutritional supplementation.

Cardiopulmonary clearance and risk assessment by a cardiologist or appropriate internist may aid in perioperative optimization.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

Presentation of the case at a multidisciplinary tumor board with radiology, gastroenterology, medical oncology, radiation

oncology, and surgical teams in attendance is optimal in the evaluation of all pancreatic lesions. This allows the case to be reviewed in an objective manner, facilitates enrollment in clinical trials, and allows the development of institutional guidelines of care among all specialties.

All patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma, whether resectable, locally advanced, or metastatic, should be offered access to a clinical trial.

A pancreaticoduodenectomy should be performed at a highvolume center (approximately more than 16 pancreatic resections per year). Resections performed at institutions below that volume have higher perioperative morbidity and mortality rates and worse oncologic outcomes.6,7

Be prepared to alter the sequence of the dissection; anatomic relationships of the tumor drive this up to the point of commitment for resection—unaffected planes should be addressed before embarking on those at risk.

Positioning

Supine position with both arms out to the side. Tuck the sheet tight under the bed to ensure bed rails are accessible for retractor placement.

Turn the head to the right with neck extended to expose the left internal jugular vein.

TECHNIQUES

DIAGNOSTIC LAPAROSCOPY

Diagnostic laparoscopy. The value of staging laparoscopy has decreased as the accuracy of CT scanning has improved.3 Laparoscopy should be performed as a prelude to potential surgical resection in selected patients who have pancreatic adenocarcinoma. We advocate selective laparoscopy on the same day as the planned resection in high-risk patients with potentially advanced disease, large (>4 cm) or borderline resectable tumors after neoadjuvant therapy, liver lesions too small to characterize or percutaneously biopsy, any ascites fluid, marked weight loss, hypoalbuminemia, and high (>1,000 U/mL) CA 19-9 levels.

The peritoneum, omentum, and surface of the liver are inspected for evidence of metastasis. A multiport technique with mobilization of the tissues and use of a laparoscopic ultrasound probe is required for a thorough examination.

INCISION

Pancreaticoduodenectomy can be performed through a midline incision from xiphoid to umbilicus or through a bilateral subcostal incision. A bilateral subcostal incision may be superior in patients with a shorter body habitus or significant obesity. A bilateral subcostal incision can be inferior in patients with a narrow costal angle and may limit exposure to the pelvis in patients with adhesions from previous pelvic surgery.

The falciform ligament is ligated, keeping it long to place over the stump of the GDA at the end of the case.

Surgical retractor of choice (Bookwalter or Thompson) is placed.

INITIAL ASSESSMENT OF RESECTABILITY

The initial portion of the procedure is an assessment of resectability.

The liver and visceral and parietal peritoneal surfaces are thoroughly assessed via a systematic four-quadrant exploration including bimanual palpation of the liver and running the small bowel from the ligament of Treitz to the cecum and palpation of the colon.

The gastrohepatic omentum is opened, and the region of the celiac axis is examined for enlarged lymph nodes. The base of the transverse mesocolon to the right of the middle colic vessels is examined for tumor involvement.

Additional information regarding the extent of the malignancy with respect to the PV, SMA, and so forth will be gleaned as the dissection progresses.

CATTELL-BRAASCH AND KOCHER MANEUVERS

The ascending colon and hepatic flexure of the colon are freed of their lateral and superior attachments using an energy device. The colonic mesentery is completely mobilized and reflected medially to expose the second and third portions of the duodenum and the head of the pancreas (FIG 4). An avascular plane between these structures will develop over the third portion of the duodenum and extend up to the inferior border of the neck of the pancreas (FIG 5). A Kocher maneuver is performed by incising the peritoneum along the lateral edge of duodenum. This incision should be extended cephalad into the foramen of Winslow. Incise the avascular ligament that tethers the third portion of the duodenum inferiorly, allowing further dissection behind the head of the pancreas, thus elevating the duodenum and pancreas from the vena cava and aorta. The duodenum is mobilized medially until the left renal vein is seen crossing over aorta. This will usually also result in fully exposing and dividing the ligament of Treitz from the right side of the patient.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree