Pancreatic Necrosectomy (Open and Laparoscopic)

Severe (necrotizing) pancreatitis results in collections of necrotic tissue in the retroperitoneum. When these become infected, antibiotics and drainage are required. In the majority of cases, drainage can be accomplished percutaneously. When repeated percutaneous drainage fails, surgical debridement of the dead tissue and drainage is the next step.

Decision making is complex and is discussed in references at the end of the chapter.

This chapter presents open necrosectomy first, followed by laparoscopic necrosectomy. This is done to illustrate the nature of the problem. In practice, laparoscopic necrosectomy has been associated with a lower mortality rate than the equivalent open drainage and is the preferred method of management when possible. The laparoscopic procedure can be repeated multiple times, if necessary, to attain adequate control of the necrotizing infectious process.

Experienced gastrointestinal endoscopists have also employed another procedure— endoscopic transgastric drainage. This is referenced at the end.

SCORE™, the Surgical Council on Resident Education, classified open pancreatic debridement for necrosis as an “ESSENTIAL UNCOMMON” and laparoscopic/endoscopic debridement for necrosis as a “COMPLEX” procedure.

STEPS IN PROCEDURE

Open Drainage

Midline or chevron incision

Thorough exploration

Identify region where necrosis is “pointing” to the peritoneal cavity

Avascular region of transverse colon mesentery

Enter the collection and obtain cultures

Follow all tongues of necrosis to obtain adequate drainage

Lesser sac toward hilum of spleen

Behind head of pancreas

Debride all easily removable tissue

Place drains or pack open

HALLMARK ANATOMIC COMPLICATIONS

Inadequate drainage

Fistula formation

Bleeding from splenic artery or other regional vessel

LIST OF STRUCTURES

Pancreas

Colon

Transverse colon

Middle colic artery and vein

Spleen

Splenic artery

Stomach

Gastroduodenal artery

Duodenum

Open Drainage of Pancreatic Necrosis (Fig. 87.1)

Technical and Anatomic Points

After induction of anesthesia, palpate the abdomen. Often an upper abdominal mass is palpable. Make an incision that will provide best access to this mass. In a very narrow-chested individual, an upper midline incision will work well. For the majority of patients, an extended left subcostal or bilateral subcostal incision will be the best approach.

Thoroughly explore the abdomen. Commonly there will be free fluid. Culture this. The peritoneal surfaces may be studded with nodules that resemble metastatic disease. These represent “fat necrosis” or “saponification” from pancreatic enzymes.

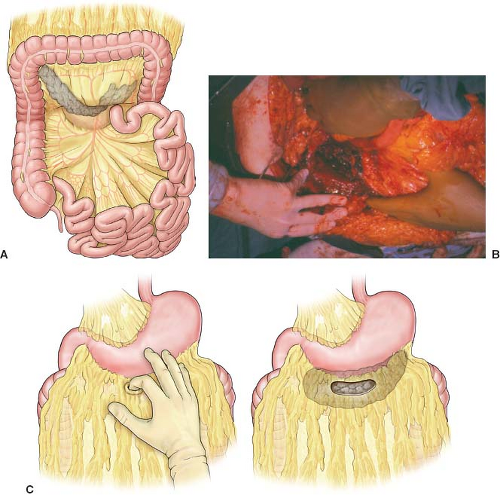

Generally, the necrotizing process is limited to the peripancreatic region, but in extreme cases it may extend down the right or left gutter behind the colon. Figure 87.1A shows the common extent of necrosis. Seek a place where the abscess appears to be “pointing”, that is, where it is close to the peritoneal cavity.

Figure 87.1 A: Extent of necrotizing process in the common situation. B: Debrided cavity at root of transverse colon mesentery. C: Alternative approach through the gastrocolic omentum (Figure A and C from Howard TJ. Chapter 130. Necrosectomy for acute necrotizing pancreatitis. In: Fischer JE, ed. Fischer’s Mastery of Surgery. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2013, with permission).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|