Overview

As the pressure to improve patient safety has grown, healthcare organizations, particularly hospitals but also larger healthcare systems, have struggled to create effective structures for their safety efforts. Although there are few studies comparing various organizational models, best practices for promoting organizational safety have begun to emerge.1–6 This chapter will explore some of these issues. The organization of safety programs in ambulatory care is discussed in Chapter 12, and, of course, myriad issues relevant to organizing an effective safety program are addressed throughout this book.

Structure and Function

Before the year 2000, few organizations had patient safety committees or officers. If there was any institutional focus on safety (in most institutions, there wasn’t), it generally lived under the organization’s top physician (sometimes a Vice President for Medical Affairs or Chief Medical Officer [CMO], or perhaps the elected Chief of the Medical Staff) or nurse (Chief Nursing Officer). In academic medical centers, safety issues were usually handled through the academic departmental structure (e.g., chair of the department of medicine or surgery), promoting a fragmented, siloed approach. When an institutional nonphysician leader did become involved in safety issues, it was usually a hospital risk manager, whose primary role was to protect the institution from liability.7 Although many risk managers considered preventing future errors to be part of their role, they rarely had the institutional clout or resources to make durable changes in processes, information technology, or culture. Larger institutions with quality committees or quality officers sometimes subsumed patient safety under these individuals or groups.

The latter structure is still common in small institutions that lack the resources to have independent safety operations, but many larger organizations have recognized the value of a separate structure and staff to focus on safety. The responsibilities of safety personnel include: monitoring and responding to the incident reporting system, educating providers and others about new safety practices (driven by the experience of others and the literature), measuring safety outcomes and developing programs to improve them, and supervising the approach to serious events (e.g., organizing root cause analyses [RCAs]) and to preventing future errors (e.g., implementing action plans after RCAs, performing failure mode and effects analyses [FMEA]) (Chapter 14).8 In addition, such personnel must work collaboratively with other departments and personnel, such as those in information technology, quality, compliance, and risk management.

Managing the Incident Reporting System

An organization interested in improving the quality of care (as opposed to patient safety) might not spend a huge amount of time and effort promoting reporting by caregivers to central administration. Why? To the extent that the quality issues of interest can be ascertained through outcome (e.g., mortality rates in patients with acute myocardial infarction, postoperative infection rates, readmission rates for patients with pneumonia) or process measures (did every patient with myocardial infarction for whom it was indicated receive a beta-blocker and aspirin?) (Chapter 3), performance assessment does not depend on the direct involvement of nurses and doctors. Instead, these data can be collected through chart review or, increasingly, by tapping into electronic data streams created in the course of care (Chapter 13). Obviously, when a quality leader identifies a “hot spot” through these measures, he or she cannot proceed without convening the relevant personnel to develop a complete understanding of the process and an action plan, but collecting the data can often be accomplished without provider participation.

Safety is different. In most cases, a safety officer or CMO will have no way of discovering errors or risky situations without receiving this information from frontline workers. Although other mechanisms (direct observation of practice, trigger tools) can identify some problems, the providers are the best repository of the knowledge and wisdom needed to understand safety hazards, near misses, and true errors, and thus to create the system changes to prevent them. As described in Chapter 14, the institutional incident reporting system is the usual, albeit imperfect, vehicle for tapping this rich vein of experience.

The patient safety officer will generally be charged with managing the incident reporting system. At small institutions, he or she will likely review every report, aggregate the data into meaningful categories (e.g., medication errors, falls), and triage the reports for further action. Based on the severity of the incidents, some reports will be simply noted, others will generate a limited analysis or an inquiry to a frontline manager, while still others will lead to a full-blown RCA. Many larger institutions have subdivided this task, selecting “category managers” to review incidents in a given domain (a pharmacist for medication errors, a nurse-leader for falls, the CMO for reports of unprofessional physician behavior; Table 14-2). The category managers are expected to review incidents within their categories, take appropriate action, and triage cases to the safety officer (or someone even higher in the organization) when the error is particularly serious or falls within an area that has regulatory or legal repercussions.

As with much of patient safety, results and culture are more important than structure. A technologically sophisticated incident reporting system will create little value if the frontline workers consider the approach to reports overly punitive, or if they see no evidence that reports are taken seriously or generate action.9 So the safety officer is well advised to invest time and energy in making clear to caregivers that their reports result in important changes. Such an investment is every bit as important as one made in purchasing and maintaining a system that collects data and produces sophisticated pie charts. I described the RCA process in Chapter 14, including some of the changes we made at University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Medical Center that markedly improved its value (Table 14-4).

Dealing with Data

Although the safety officer will generally not be as data driven as the quality officer (for the reasons described above), he or she will have a steady stream of inputs that can be important sources of understanding and action. Some of these will be generated by the incident reporting system; here, it is important to use the information effectively while recognizing that voluntary reports capture only a small (and nonrandom) subset of errors, and that they cannot be used to determine rates of errors or harm.10,11 An additional problem with incident reports is that nurses submit them far more frequently than physicians do, so they tend to underemphasize issues that physicians see (such as diagnostic errors, Chapter 6) and overemphasize nursing-related harms (e.g., falls).12,13 Malpractice claims are an even more serendipitous source of safety concerns (Chapter 18). Several recent studies have illuminated an important point: there is no one “right” way to view an organization’s safety, and the safety leader must look at a dashboard with multiple “dials.”14–16 In my judgment, to gain a complete view of the “elephant of patient safety,”15 a hospital safety leader should regularly review at least a dozen sources of data (Table 22-1).

|

For safety problems that can be measured as rates (such as hospital-acquired infections, Chapter 10), the role of the safety officer (assuming this is his or her domain; in large institutions, an infection preventionist may be charged with this task) becomes more like the quality officer: studying the data to see when rates have spiked above prior baselines or above local, regional, or national norms (“benchmarks”). In these circumstances, the safety officer will complete an in-depth analysis of the problem and develop an action plan designed to improve the outcomes.

Increasingly, safety officers will need to audit areas that have been the subject of regulatory requirements or new institutional policies. Such audits are best done through direct observation, and backsliding should be expected. In fact, the safety officer should be skeptical if an audit six months after implementation of a new policy demonstrates 100% compliance with the practice: there is an excellent chance that these are biased data and more should be done to get a true snapshot of what is really happening.

Finally, as medical records become electronic (Chapter 13), innovative methods for screening caregiver notes, lab results and medication orders (such as via trigger tools, Chapter 14), operative reports, and discharge summaries will generate new and useful safety information.17–19 More and more of this work will involve real-time surveillance systems, with automatic “just-in-time” feedback to providers rather than the traditional process of (retrospective) audit and (markedly delayed) feedback.20

Some of the most important safety data will be the results of patient safety culture surveys. There are several well-constructed, validated surveys that can be used for this purpose; a few have been used at hundreds, or even thousands, of institutions, meaning that an institution’s results can be compared with those from like institutions or units (e.g., other academic medical centers, or other intensive care units [ICUs]).21,22 As I mentioned in Chapter 15, although it is appealing (after all, humans like simple explanations, even when they’re wrong) to think of institutions (such as hospitals or large healthcare delivery systems) as having organization-wide safety cultures, work by Pronovost, Sexton, and others has demonstrated that safety culture tends to be local: even within a single hospital, there will often be huge variations in culture between units down the hall from one another.23,24

The safety officer’s job, then, is to ensure administration of the surveys and a reasonable response rate, that the results are thoughtfully analyzed, and—as always—that the data are converted into meaningful action. For clinical units with poor safety culture, it is critical to determine the nature of the problem. Is it poor leadership, and, if so, is leadership training or a new leader required? Is it poor teamwork, and, if so, should we consider a crew resource management or other teamwork training program (Chapter 15)? And is there something to be learned from units with excellent culture that can be used to inform or stimulate change in the more problematic units?25

Finally, there is the challenge of integration and prioritization. The patient safety officer who monitors all of these data sources will have far more safety targets than he or she can possibly address in a year. This means that one crucial job is to help an organization prioritize among many worthwhile goals. It is natural that such prioritization will tend to elevate items required by regulators or accreditors over those that are not, measurable targets over softer ones, and efforts to change processes and structures over efforts to change culture and attitudes. The effective (and durably employed!) safety officer lives in the real world and addresses what needs to be addressed, but also works to counteract these biases when that is best for patients. For example, implementing a teamwork training initiative or an institution-wide program to prevent diagnostic errors may not be required, and their payoffs may be years away and hard to measure. The safety officer who believes that these activities are important for patients will—somehow—find the money, time, and political will to place them on the organization’s agenda.

Strategies to Connect Senior Leadership with Frontline Personnel

Recognizing that an effective safety program depends on connecting the senior leadership (who control major resources and policies) with what is truly happening on the clinical units, and further appreciating that incident reporting systems paint a terribly incomplete picture of this frontline activity, many healthcare organizations have developed strategies to connect senior leaders with caregivers. The two most popular ways of accomplishing this are Executive Walk Rounds and “Adopt-a-Unit.”

Executive Walk Rounds are the healthcare version of the old business leadership strategy of “Managing by Walking Around” (MBWA).26–29 At some interval (some institutions do Walk Rounds weekly, others monthly), the safety officer will accompany another member of the senior leadership team (e.g., CEO, COO, CMO) to a clinical unit—a medical floor, the emergency department, the labor and delivery suite, or perhaps an operating room. The visits are usually preannounced. Although the unit manager is generally present for the visit, the most important outcome is a frank discussion (with senior leadership spending more time listening than talking) about the problems and errors on the unit, and brainstorming solutions to these problems. Some institutions have formalized these visits with a script; a sample one is shown in Box 22-1.

Opening statements: “We are moving as an organization to open communication and a blame-free environment because we believe that by doing so we can make your work environment safer for you and your patients” “We’re interested in focusing on the system and not individuals (no names are necessary)” “The questions are very general. To help you think of areas to which the questions might apply, consider medication errors, miscommunication between individuals (including arguments), distractions, inefficiencies, invasive treatments, falls, protocols not followed, and so on” Questions to ask:

Closing comment: “We’re going to work on the information you’ve given us. In return, we would like you to tell two other people you work with about the concepts we’ve discussed in this conversation” Reproduced with permission from Frankel A. Patient Safety Leadership Walkrounds. Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI); 2004. Available at: http://www.ihi.org/knowledge/Pages/Tools/PatientSafetyLeadershipWalkRounds.aspx. |

Another strategy (not mutually exclusive, but institutions tend to favor one or the other) is “Adopt-a-Unit.”30 Here, rather than executives visiting a variety of clinical areas around the hospital to get a broad picture of safety problems, one senior leader adopts a single unit and attends relevant meetings with staff there (perhaps monthly) for a long period (6–12 months). This method, pioneered at Johns Hopkins, has the advantage of more sustained engagement and automatic follow-through, and the disadvantage of providing each leader a more narrow view of the entire institution. Given that there are only so many senior leaders to go around, the Adopt-a-Unit strategy will generally mean that certain units will be neglected. For this reason, it is less popular than Executive Walk Rounds. However, for units experiencing important safety challenges or showing evidence of poor culture, this method, with its sustained focus, may have real value.

Whichever method is chosen, these efforts will be most useful if providers sense that senior leadership takes their concerns seriously, leaders demonstrate interest while being unafraid to show their ignorance about how things really work on the floor, and the frontline workers later learn about how their input led to meaningful changes.

Strategies to Generate Frontline Activity to Improve Safety

Although connecting providers to senior leadership is vitally important, units must also have the capacity to act on their own. One of the dangers of an organizational “safety program” can be that individual clinical units will not be sufficiently active and independent—sharing stories of errors, problem solving, and doing the daily work of making care safer. Because many such efforts do not require major changes in policies or large infusions of resources, safety officers and programs need to create an environment and culture in which such unit-based problem solving is the norm, not the exception.

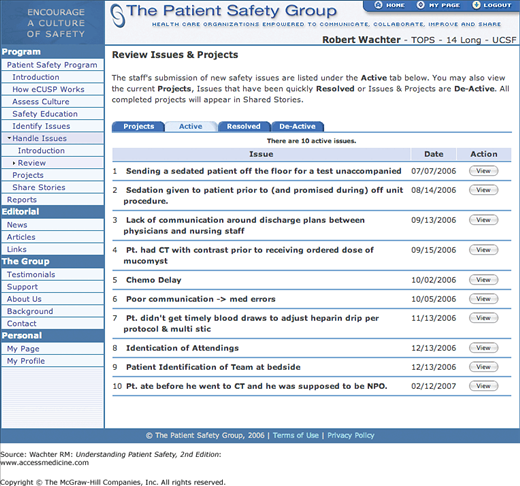

While some units will instinctively move in this direction (often as an outgrowth of strong local leadership and culture), others will need help. Many of the programs discussed previously (such as teamwork training) should leave behind an ongoing organizational structure that supports unit-based safety. For example, at UCSF, after more than 400 providers of all stripes participated in a crew resource management/teamwork training program, we launched a unit-based safety team on our medical ward that collected stories, organized interdisciplinary case conferences, and convened periodically to problem solve.31 Their work was supported by e-CUSP, an electronic project management tool created for this purpose (Figure 22-1).32,33

Developing this kind of unit-based safety enterprise requires training, leadership, and some resources (a small amount of compensation for the unit-based champions, time for the group to meet, and—of course—food). It is also important to sort out the “cross-walk” between the unit-based efforts and the larger institutional safety program. On the one hand, the unit-based team must be free to discuss errors, develop educational materials, and problem solve without being encumbered by the organizational bureaucracy. On the other hand, the unit-based program cannot completely bypass the institutional incident reporting system, and it is vital that central leadership rapidly learns of major errors that should generate broader investigations (i.e., RCAs) or mandatory reports to external organizations.

Dealing with Major Errors and Sentinel Events

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree