Oral Health: Introduction

Although the nation’s oral health is believed to be the best it has ever been, oral diseases remain common in the United States. In May 2000, the first report on oral health from the US Surgeon General, Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General, called attention to a largely overlooked epidemic of oral diseases that is disproportionately shared by Americans: This epidemic strikes in particular the poor, young, and elderly. The report stated that although there are safe and effective measures for preventing oral diseases, these measures are underused. The report called for improved education about oral health, for a renewed understanding of the relationship between oral health and overall health, and for an interdisciplinary approach to oral health that would involve primary care providers.

Dental Anatomy & Tooth Eruption Pattern

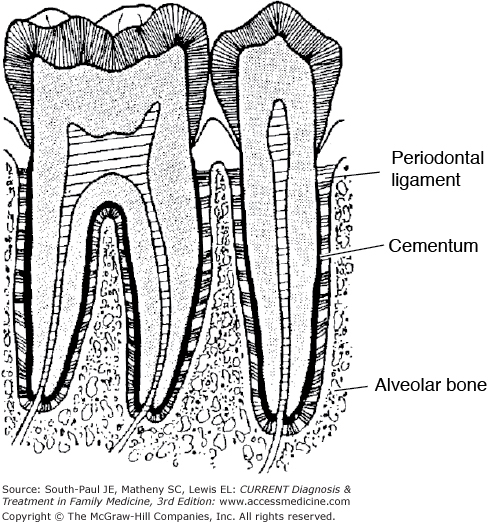

In utero, the 20 primary teeth evolve from the expansion and development of ectodermal and mesodermal tissue at approximately 6 weeks of gestation. The ectoderm forms the dental enamel and the mesoderm forms the pulp and dentin. As the tooth bud evolves, each unit develops a dental lamina that is responsible for the development of the future permanent tooth. The adult dentition is composed of 32 permanent teeth. Figure 45-1 shows the anatomy of the tooth and supporting structures. Table 45-1 outlines the eruption pattern of the teeth.

| Teeth | Eruption Date |

|---|---|

| Primary dentition | |

| Mandibular central incisor | 6 mo |

| Maxillary central incisor | 7 mo |

| Mandibular lateral incisor | 7 mo |

| Maxillary lateral incisor | 9 mo |

| Mandibular first molar | 12 mo |

| Maxillary first molar | 14 mo |

| Mandibular canine | 16 mo |

| Maxillary canine | 18 mo |

| Mandibular second molar | 20 mo |

| Maxillary second molar | 24 mo |

| Permanent dentition | |

| Mandibular central incisors | 6 y |

| Maxillary first molars | 6 y |

| Mandibular first molars | 6 y |

| Maxillary central incisors | 7 y |

| Mandibular lateral incisors | 7 y |

| Maxillary lateral incisors | 8 y |

| Mandibular canines | 9 y |

| Maxillary first premolars | 10 y |

| Mandibular first premolars | 11 y |

| Maxillary second premolars | 11 y |

| Mandibular second premolars | 11 y |

| Maxillary canines | 11 y |

| Mandibular second molars | 12 y |

| Maxillary second molars | 12 y |

| Mandibular third molars | 17–21 y |

| Maxillary third molars | 17–21 y |

Dental Caries

Dental caries (tooth decay) is the single most common chronic childhood disease, five times more common than asthma and seven times more common than hayfever among children 5-7 years of age. Minority and low-income children are disproportionately affected. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), among children aged 2-11 years, 21% have had untreated tooth decay in primary teeth, and of these, 32% are Mexican American, 27% are African American, and 18% are white. In addition, one-third of persons of all ages have untreated decay, 8% of adults older than 20 years of age have lost at least one permanent tooth to dental caries, and many older adults suffer from root caries.

Dental caries is a multifactorial, infectious, communicable disease caused by the demineralization of tooth enamel in the presence of a sugar substrate and of acid-forming cariogenic bacteria that are found in the soft gelatinous biofilm plaque (Figure 45-2). Thus, the development of caries requires a susceptible host, an appropriate substrate (sucrose), and the cariogenic bacteria found in plaque. Streptococcus mutans (also known as mutans streptococci [MS]) is considered to be the primary strain causing decay. Additionally, when plaque is not regularly removed, it may calcify to form calculus (tartar) and cause destructive gum disease.

Finally, the development of caries is a dynamic process that involves an imbalance between demineralization and remineralization of enamel. When such an imbalance is caused by environmental factors such as low pH or inadequate formation of saliva, dissolution of enamel occurs and caries result.

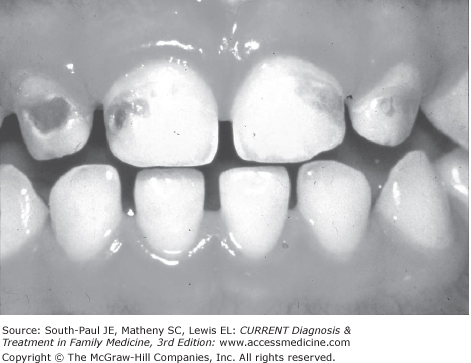

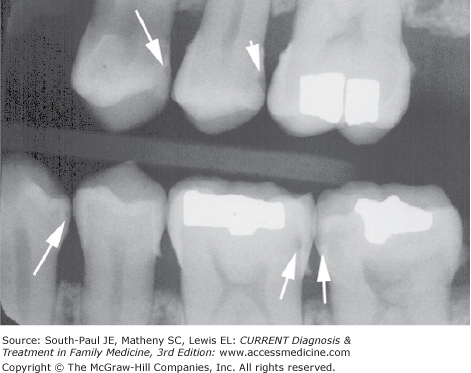

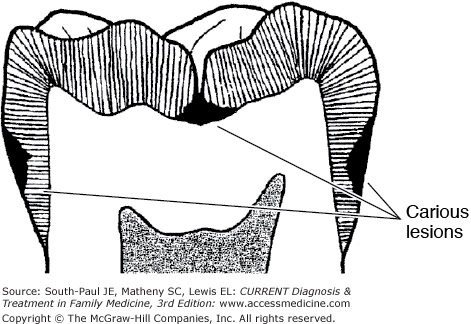

When enamel is repeatedly exposed to the acid formed by the fermentation of sugars in plaque, demineralized areas develop on the tooth surfaces, between teeth, and on pits and fissures. These areas are painless and appear clinically as opaque or brown spots (Figures 45-3, 45-4, and 45-5). If infection is allowed to progress, a cavity forms that can spread to and through the dentin (the component of the tooth located below the enamel) and to the pulp (composed of nerves and blood vessels; an infection of the pulp is called pulpitis), causing pain, necrosis, and, perhaps, an abscess.

Carious lesions progress at various rates and occur at many different locations on the tooth, including the sites of previous restorations. Demineralized lesions (white or brown spots) generally occur at the margins of the gingiva and can be detected visually; they may not be seen on radiographs. Advanced carious lesions such as those spread through dentin can be detected clinically or, if they occur between the teeth, by radiographs. Root caries, commonly seen in older adults, occur in areas from which the gingiva has receded.

Dental professionals use a dental explorer to detect early caries in the grooves and fissures of posterior teeth. To diagnose secondary caries (caries formed at the site of restorations), dental professionals use digitally acquired and post-processed images.

Caries can develop at any time after tooth eruption. Early teeth are principally susceptible to caries caused by the transmission of MS from the mouth of the caregiver to the mouth of the infant or toddler. This type of caries is called early childhood caries (ECC) or baby bottle tooth decay (BBTD). According to the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry, ECC “is defined as ‘the presence of one or more decayed (noncavitated or cavitated lesions), missing (due to caries), or filled tooth surfaces’ in any primary tooth in a child 71 months of age or younger.” In children younger than 3 years, any sign of smooth-surface caries is called severe early childhood caries (S-ECC). Children with a history of ECC or S-ECC are at a much higher risk of subsequent caries in primary and permanent teeth. Risk factors for caries development are shown in Table 45-2.

| Risk Factors for Childhood Caries | Risk Factors for Adult Caries |

|---|---|

Dietary practices: frequent consumption of foods and bever- ages containing sugars (juice, milk, formula, soda) and sticky foods Frequent bottle- and breastfeeding on demand Maternal or sibling caries Repetitive use of a “sippy cup” Poor oral hygiene Inadequate fluoridation Lack of dental visits | Physical and medical disabilities Existing restorations or oral appliances Inadequate salivary flow Medications that produce dry mouth Radiation therapy Low socioeconomic status |

ECC contributes to other health problems, including chronic pain, poor nutritional practices, and low self-esteem, which may lead to lack of self-esteem among older children and a great reduction in their ability to succeed in life.

The risk factors for adult caries are similar to those for childhood caries, including those listed in Table 45-2.

Fluoride, the ionic form of the element fluorine, is widely accepted as a safe and effective practice for the primary prevention of dental caries. Fluoride slows or reverses the progression of existing tooth decay by (1) being incorporated into the enamel before tooth eruption, (2) inhibiting demineralization, (3) enhancing remineralization, and (4) inhibiting bacterial activity in plaque. Unfortunately, only 57% of the US population has access to community water fluoridation, according to the CDC fluoridation census in 2000. Systemic fluoride supplements (tablets, drops, lozenges) are recommended for children older than 6 months who are at high risk of the development of caries, for infants with ECC, to children living in non-fluoridated water areas between 6 months and 16 years and for adults whose water is not fluoridated or who have diseases that produce a decrease in salivary flow, receding gums, or mental or physical disabilities. A supplemental fluoride dosage schedule is shown in Table 45-3. Topical fluoride supplements such as gels and varnishes are highly concentrated fluoride products that are professionally applied by a dental health provider or a parent (for gels). Varnishes, which are less toxic than gels and more effective than mouth rinses, are applied three times a week, once a year by disposable brushes, cotton-tipped applicators, or cotton pellets. To learn more about fluoride varnish application visit the Smiles for Life Web site, http://www.smilesforlifeoralhealth.org/.

Fluoride ion level in drinking water (ppm)a | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Age | <0.3 ppm | 0.3-0.6 ppm | >0.6 ppm |

Birth-6 mo | None | None | None |

6 mo-3 y | 0.25 mg/db | None | None |

3-6 y | 0.50 mg/d | 0.25 mg/d | None |

6-16 y | 1.0 mg/d |