Operative Treatment of Rectal Prolapse: Perineal Approach (Altemeier and Modified Delorme Procedures)

Valerie Bauer

DEFINITION

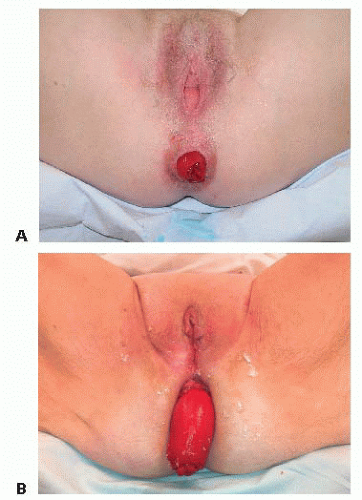

Rectal prolapse is a “falling down” of the rectum caused by weakness in surrounding supportive tissues. Straining during constipation secondary to functional disorders of elimination (anismus) and anatomic causes of outlet obstruction such as middle and anterior pelvic organ prolapse (enterocele, sigmoidocele, rectocele, hysterocele, and cystocele) are major risks factors. Other risk factors include low anterior cul-de-sac, multiparity, anal sphincter muscle weakness, levator diastasis, redundant rectosigmoid, and neurologic disease.1 Recognition of the type of prolapse determines operative approach. Internal intussusception includes all layers of the rectum and rectosigmoid through the rectum and into the anal canal but not beyond. Partial thickness prolapse involves protrusion of the redundant mucosal layer of the rectum for a distance of 1 to 3 cm from the anal margin (FIG 1A). True prolapse consists of a full-thickness protrusion of all layers of the rectum through a sliding hernia of the cul-de-sac so that the rectum is out of the body (FIG 1B).2

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Prolapsed and incarcerated internal hemorrhoids may appear similar to rectal prolapse. The appearance of concentric folds differentiate rectal prolapse from hemorrhoidal prolapse, which appears as radial invaginations relative to anatomic location of the internal hemorrhoidal cushions.

Enterocele and sigmoidocele is the combined prolapse of posterior vaginal wall and herniation of the respective segments of bowel through the anterior cul-de-sac, which may cause anterior rectal prolapse and bleeding.

Hysterocele and cystocele involve vaginal prolapse, which can also contribute to the “pulling down” of the fascial support of the rectum.

Rectal cancer or polyps may act as a lead point from which colorectal prolapse occurs, hence underscoring the importance of diagnostic colonoscopy to rule out proximal mucosal pathology as a cause of intussusception.

Inflammatory colitides should be considered for findings of isolated rectal ulceration, seen in the anterior rectum at the point of retroperitoneal fixation, where repeated internal prolapse forms. A discrete anterior solitary rectal ulcer is approximately 4 to 10 cm from the anal verge.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Successful perineal proctosigmoidectomy for full-thickness prolapse (Altemeier) and mucosectomy for partial mucosal prolapse (modified Delorme) depends on proper determination of type of prolapse. Therefore, accurate history and recognition of physical examination findings is of paramount importance.

Surgery for isolated internal prolapse is currently not performed in lieu of conservative management to include dietary and behavioral modifications, such as pelvic muscle rehabilitation for treatment of functional elimination disorders. However, future understanding of the relationship between posterior internal pelvic organ prolapse and middle/anterior pelvic organ prolapse may redefine guidelines for surgical indication using a multidisciplinary approach to multiorgan repair to include colorectal, urogynecology, and urology subspecialists.

A thorough history must identify causes of constipation (and excessive straining) such as dietary and social behaviors (inadequate fiber intake, sedentary lifestyle), medications, and medical conditions (hypothyroidism, electrolyte disturbances, interstitial cystitis, pelvic organ prolapse, anxiety, or psychiatric disturbances).

Past surgical history of multiple prior pelvic operations (hysterectomy, sacrocolpopexy, coloproctostomy) increases operative risk for complication. Prior abdominal repair of rectal prolapse with rectosigmoid resection is a contraindication to

perineal proctectomy due to altered mesenteric blood flow and risk for distal ischemia.

Risk factors for colorectal cancer and polyps is determined through family history and personal history of changes in bowel habits, bleeding, and results of most recent colonoscopy.

Obstetric and urogynecologic history aims to determine risk factors for anal muscle weakness and pelvic organ prolapse, such as number of intrauterine pregnancies, term vaginal deliveries, large-birth-weight baby, prolonged labor, use of forceps, high-grade vaginal tear, absence of controlled episiotomy, and urinary incontinence. Additionally, nulliparity has been associated with higher incidence of rectal prolapse as well.3,4

Initial presentation is commonly described as “something falling out that has to be pushed back in.” Other possible initial complaints include a feeling of fullness in the pelvis, severe pain (levator muscle spasm), bleeding, incomplete evacuation with splinting or positional maneuvers to eliminate, excessive straining, mucus or fecal staining, perineal discomfort and burning (due to chronic moisture), improved pain on lying down, and fecal urgency with “nothing there.”

Initial anorectal examination is done in prone jackknife or lateral Sims position. It begins with inspection of the perianal skin. In the absence of grossly visible prolapse at the anal margin, a patulous anus, fecal smearing, and thickening (lichenification) of anoderm due to chronic perineal moisture suggests rectal or mucosal prolapse. The appearance of the anus may be flat due to loss of compliance and function of the pelvic floor musculature (perineal descent syndrome). Visible scars due to episiotomy or prior anorectal surgery should be noted.

Vaginal examination may reveal anterior vaginal prolapse (cystocele) or posterior vaginal wall prolapse (rectocele, enterocele).

Digital rectal examination determines anal sphincter tone and function. Patients with full-thickness prolapse often have little to no resting or squeeze tone due to levator muscle separation and pudendal nerve damage. Patients are asked to squeeze to give some indication of sphincter strength (diagnostic of fecal incontinence). Digital palpation of the perineal body may also reveal anterior thinning and sphincteric defect due to prior obstetric injury or other mechanisms of levator separation.

Digital compression in the anterior rectum may reveal rectocele. The patient should be asked to strain during digital palpation to evaluate for paradoxical contraction or lack of anal sphincter relaxation (indicative of functional elimination disorder, anismus). Similarly, exaggerated strain may reproduce internal prolapse and/or rectocele, which is appreciated by luminal protrusion into the posterior wall of the vagina.

Anorectal examination uses a side-viewing anoscope (Hirschman) to evaluate the anal canal. Internal hemorrhoids may or may not prolapse with rectal prolapse. However, they may be inflamed, bleeding, or thrombosed due to excessive straining from outlet obstruction caused by the prolapse. Patients with rectal prolapse complain more of hemorrhoidal disease due to a lack of awareness of rectal prolapse. Rigid proctosigmoidoscopy allows for evaluation of the rectum and sigmoid up to 25 cm from the anal verge for evidence of prolapse or other mucosal disease. Anterior solitary rectal ulcer is classically seen between the first and second valve of Houston and represents the point of recurrent internal prolapse. Release of air insufflation and having the patient bear down as the scope is withdrawn will prolapse redundant tissue into the aperture of the proctosigmoidoscope, which is diagnostic of rectal prolapse in the office.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Having the patient squat or strain, especially after administration of fleet enema, will help protrude the prolapsed rectum. This test is performed in the clinic and is diagnostic of rectal prolapse (toilet test).

Defecography uses fluoroscopic imaging to evaluate the structure and function of posterior, middle, and anterior pelvic floor during the three phases of elimination—rest, squeeze, and strain. It may be used to diagnose rectal prolapse if it is not clinically evident. Pelvic floor structures are visualized using thick barium paste instilled into the rectum, a barium-impregnated tampon in the vagina, oral contrast for small bowel, and intravenous contrast for visualization of the bladder. Internal rectal prolapse is demonstrated during strain in image (FIG 2A,B).

Pelvic floor physiology testing determines preoperative functional baseline of the anal sphincter, especially when there is associated fecal incontinence. These tests include anal manometry, rectal sensation, and anal electromyography (EMG).

Pudendal nerve terminal motor latency (PNTML) determines neurogenic impediment to anal sphincter muscle function.

Although pudendal neuropathy is not a contraindication for repair of rectal prolapse, its presence may predict poor outcome in improvement of fecal incontinence associated with rectal prolapse after surgery and should be discussed with the patient preoperatively.5

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree