Oncoplastic Breast Surgery

Kristine E. Calhoun

Benjamin O. Anderson

DEFINITION

Breast-conserving therapy was first introduced as a treatment option for women with breast cancer beginning in the 1970s, with multiple clinical trials having since demonstrated equivalency in terms of overall survival between lumpectomy with radiation and mastectomy.1,2

For breast conservation to be effective, the cancer must be resected with adequate surgical margins while simultaneously maintaining the breast’s shape and appearance. Unfortunately, satisfying these dual goals may prove to be challenging.3

In a traditional lumpectomy, the skin is opened, the tumor removed, and the wound closed without any specific effort being made to obliterate the internal cavity. Closing the remaining fibroglandular tissue may result in cosmetic defects if alignment of the breast tissue is suboptimal. Although such an approach may work well for smaller tumors, declivity of the skin and/or displacement of the nipple-areolar complex (NAC) may be the end result if the lesion removed from the breast is sizable.

In 1994, Werner P. Audretsch was one of the first to advocate the use of “oncoplastic surgery” for repair of partial mastectomy defects by combining the techniques of volume reduction with immediate flap reconstruction.4 Although initially used to describe partial mastectomy combined with large myocutaneous flap reconstruction using the latissimus dorsi or the rectus abdominis muscles, oncoplastic surgery currently refers to a series of surgical approaches that use partial mastectomy and breast flap advancement to address tissue defects following wide resection.

ANATOMY

One of the fundamental challenges for the oncoplastic breast surgeon is to determine how the individual cancer is distributed within the breast and to assess whether the lesion can be resected as a single en bloc fibroglandular resection.

The modern anatomic analysis of ductal anatomy suggests that the number of major ductal systems is probably fewer than 10. The size of ductal segments can be incredibly variable, with some presenting as a narrow “pie slice” of tissue; in other cases, a single ductal segment can occupy up to 25% of the total breast volume.6

Not all ducts pass radially from the nipple to the periphery of the breast, as some travel directly back from the nipple toward the chest wall. Single ductal segments may radiate to the sternal (medial) and clavicular (superior) aspects of the breast, with two or three ductal branches layered on each other, creating a fuller pad of fibroglandular tissue in the axillary (lateral) and abdominal (inferior) aspects of the breast.7 Although the ductal branches appear to interdigitate with each other within the breast parenchyma, the segments do not communicate with each other via ductal anastomoses.

In contrast to breast ductal anatomy, the fibroglandular tissue of the breast has a rich anastomotic circulatory bed, which allows oncoplastic resection and mastopexy fibroglandular advancement to be safely performed with minimal threat to tissue viability. This well-collateralized breast vasculature allows the surgeon to remodel large amounts of fibroglandular tissue within the skin envelope without major risk of breast devascularization and subsequent necrosis.

The axillary and internal mammary arteries are the most common origins of the arterial blood supply of the breast. By maintaining communication with one of these two arterial connections, adequate blood supply to the breast parenchyma is maintained during tissue advancement and mastopexy closure.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Patients should undergo standard preoperative history and physical, with special attention given to any prior breast surgical history, including the placement and location of breast implants.

Tissue biopsy, preferably using core needle sampling, should be performed and conclusive proof of malignancy documented, with mandatory internal review of all external pathology slides required at our institution.

Every effort should be made to make the tissue diagnosis by needle sampling, as an excisional biopsy scar may complicate the placement of the subsequent lumpectomy incision.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Patients considered for oncoplastic lumpectomy should undergo a standard preoperative breast imaging workup, which typically includes a combination of mammography and ultrasound, with or without breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Although mammography may underestimate the extent of disease, especially if ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) is present, it is still warranted and is often the initial diagnostic study.8

Although still controversial, the use of MRI may contribute greatly to the surgeon’s ability to preoperatively determine the extent of disease present, especially for more mammographically subtle or occult cancers. Compared with mammographic and ultrasound images, the extent of disease seen on MRI may correlate best with the extent of tumor found at pathologic evaluation.

Although sensitivity is high, MRI has a low specificity of 67.7% in the diagnosis of breast cancer before biopsy.9 Up to one-third of MRI studies will show some area of enhancement

that needs further assessment but ultimately prove to be histologically benign breast tissue.3

For cancers containing both invasive and noninvasive components, a combination of imaging methods (mammography with magnification views, ultrasonography, and/or MRI) may yield the best estimate of overall tumor size.10

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

The indications, as well as the contraindications, for oncoplastic surgery are the same as those of traditional breastconserving surgery. In general, such techniques are only offered to those otherwise believed to be breast preservation candidates, including patients with single quadrant disease and individuals who can tolerate and have access to postsurgical radiation therapy.

The techniques described in this chapter are easily learned and implemented by breast surgeons, even those lacking formal plastic surgery training.

Preoperative Planning

While planning oncoplastic resections, as with traditional lumpectomy, the surgeon needs to accurately identify the area requiring removal, which is often aided by the use of preoperatively or perioperatively placed localization wires.

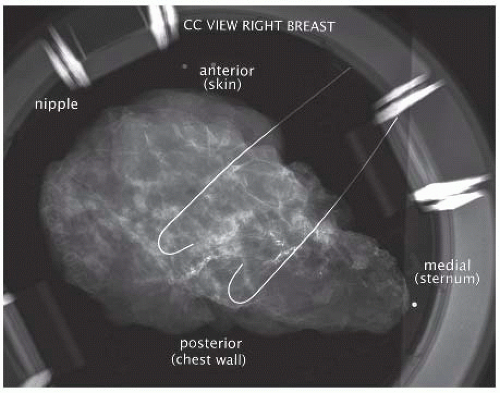

Single wire localization for larger breast lesions may be more likely to result in positive margins, because the surgeon lacks landmarks to determine where the true boundaries of nonpalpable disease are located. For such scenarios, multiple bracketing wires may assist the surgeon in achieving complete excision at the initial intervention (FIG 1).

Positioning

Before the procedure, consideration should be given to marking skin landmarks with the patient in the upright sitting position.

Relevant landmarks to be identified include the inframammary crease, the anterior axillary fold at the pectoralis major muscle, the posterior axillary fold of the latissimus dorsi muscle, the sternal border of the breast, and the periareolar circle. Identifying these structures with the patient in the sitting position is very important to the final cosmetic outcome, because these sites may be challenging to accurately locate once the patient is anesthetized and lying supine on the operating room (OR) table.

Approach

The patient should be supine on the OR table with the arms abducted.

It is preferable to have both breasts prepped and draped into the field so that visual comparison with the patient in a beach chair position is possible as the wound is closed. Such an approach allows the surgeon to identify areas of unsightly tugging or dimpling inadvertently created during closure so that they can be addressed at that time.

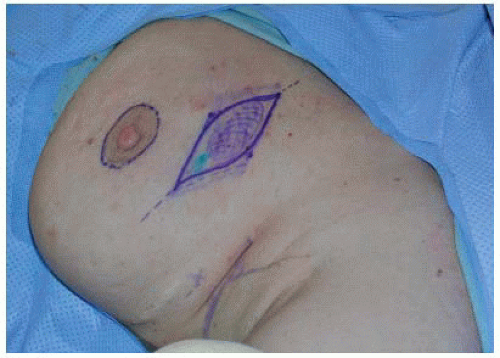

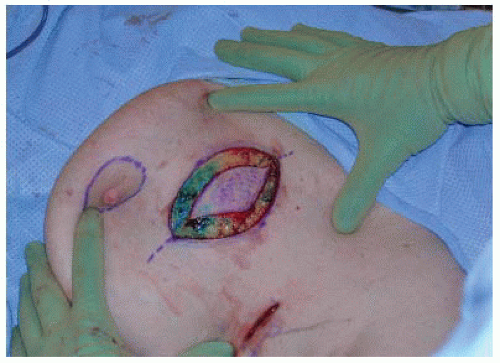

Multicolored inking can help orient the specimen and is best performed by the operating surgeon (FIG 2).

TECHNIQUES

PARALLELOGRAM MASTOPEXY LUMPECTOMY

The most basic of the oncoplastic techniques, this involves removal of the skin island located directly superficial to the known disease and is most commonly used for superior pole or lateral cancers.11

For upper inner quadrant lesions, the skin island excisions should be small or performed using a simple reapproximation of breast tissue and skin without removal of any skin island.12

Removal of the overlying parallelogram of skin avoids excessive, redundant skin from being left behind after excision and helps prevent declivity.

Be cautious when designing the skin ellipse, because removal of too broad of an island can cause substantial shifting of the NAC.

A rounded parallelogram with two equal length lines is drawn, thus marking the skin island to be excised in conjunction with the underlying target lesion and surrounding tissues (FIG 3). For lesions in the upper breast, incisions should be curvilinear, whereas lesions

located within the lower breast, including the 3 o’clock and 9 o’clock positions, should have a radially placed parallelogram.

FIG 3 • The rounded parallelogram, with two equal line lengths, to excise a skin island en bloc with the tumor.

The proposed skin incision is made to breast parenchyma (FIG 4).

After excision of the skin island, short-distance mastectomy-type skin flaps are raised along both sides of the wound.

Dissection is carried down to the chest wall, the breast gland is lifted off the pectoralis muscle (FIG 5), and a standard tumor resection is performed.

Four to six marking clips are typically placed at the base of the defect within the surrounding fibroglandular tissue.

Once resection is complete and hemostasis obtained, the fibroglandular tissue at the level of the pectoralis fascia is undermined so that breast tissue advancement can be performed over the muscle (FIG 6).

FIG 4 • The skin of the rounded parallelogram is divided with a scalpel down to the breast parenchyma.

The margins of the residual cavity are then shifted together by the advancement of breast tissue over muscle and the defect is sutured at the deepest edges using 3-0 absorbable suture. The direction of tissue advancement can be adjusted depending on the location of the fibroglandular defect and the excess tissue that can be shifted to close it. The goal of the mastopexy is to perform as complete of a closure over the pectoralis muscle as possible to discourage communication between the anterior skin and the deeper tissues (FIG 7).

The superficial tissue layer is closed with interrupted subdermal absorbable sutures (we use 3-0 sutures), whereas the skin is closed by absorbable subcuticular sutures (we use 4-0 sutures) in routine fashion (FIG 8).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree