Neurogenic Thoracic Outlet Syndrome Exposure and Decompression: Transaxillary

George J. Arnaoutakis

Thomas Reifsnyder

Julie Ann Freischlag

DEFINITION

In 1821, Sir Astley Cooper recognized the constellation of neurovascular symptoms involving the thoracic outlet. Ochsner called this the scalenus anticus syndrome in 1936 and described the presence of muscle abnormalities secondary to repetitive trauma. Peet assigned this condition its contemporaneous moniker thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) in 1966.1

TOS is a condition defined as compression of one or more of the neurovascular structures contained within the thoracic outlet.

The thoracic outlet is a narrowly defined anatomic region encompassing the space between the neck and the shoulder, cephalad to the thoracic cavity, and beneath the clavicle. From the surgeon’s point of view the thoracic outlet can be visualized as an anatomic triangle: the two sides being the anterior and middle scalene muscles with the 1st rib serving as the base of the triangle. The scalene muscles, which originate from the lower cervical spine, may hypertrophy with repetitive neck motion or minor trauma. This hypertrophy is believed to contribute to compression of thoracic outlet structures.

TOS is subdivided into three discrete entities.

Neurogenic

Venous

Arterial

Appropriate classification of the type of TOS is important in guiding perioperative management, as well as surgical approach. This chapter focuses on transaxillary decompression and 1st rib resection for neurogenic TOS.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Carpal tunnel syndrome

Ulnar nerve compression

Rotator cuff tendinitis

Pectoralis minor syndrome

Cervical spine strain

Cervical disc disease

Cervical arthritis

Brachial plexus injury

Fibromyositis

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

A careful history and physical examination enables proper classification of TOS.

The neurogenic form accounts for the majority of cases in modern series (>95%).2 Symptoms of neurogenic TOS, which is more prevalent in women, include paresthesia; pain; and impaired strength in the affected shoulder, arm, or hand along with occipital headaches and neck discomfort. There is commonly an antecedent history of hyperextension neck injury or repetitive neck trauma. Patients frequently manifest tenderness on palpation in the supraclavicular fossa over the anterior scalene muscle. A careful vascular physical examination should confirm the presence of normal circulation.

Three physical examination maneuvers support the diagnosis of neurogenic TOS.

Rotation of the neck and tilting of the head to the opposite side elicit pain in the affected arm.

The upper limb tension test in which the patient first abducts both arms to 90 degrees with the elbows in a locked position, then dorsiflexes the wrists, and finally, tilts the head to the side. Each subsequent step imparts greater traction on the brachial plexus, with the first two positions causing discomfort on the ipsilateral side and the head-tilt position causing pain on the contralateral side.

During the elevated arm stress test (EAST), the patient raises both arms directly above the head and repeatedly opens and closes the fists. Characteristic upper extremity symptoms arise within 60 seconds in patients with neurogenic TOS.

Approximately 4% of patients with TOS present with venous involvement. Venous TOS patients typically present with acute onset of dull aching pain of the upper extremity associated with arm edema and cyanosis. Paresthesias may be present but are due to hand swelling instead of thoracic outlet nerve involvement. A history of strenuous and repetitive work or athletics involving the affected extremity is common, and most patients are young. This specific condition is also known as Paget-Schroetter syndrome or effort vein thrombosis, as the entrapped subclavian vein has progressed to thrombosis. Some patients will present less acutely with nonthrombotic subclavian vein occlusion or stenosis manifested by intermittent swelling with activity. Regardless, the etiology of venous TOS is mechanical, and treatment is ultimately aimed at eliminating not only the venous obstruction but also the muscular bands and ligaments that have entrapped and damaged the vein.

Arterial TOS typically presents in one of three ways: (1) asymptomatic, (2) arm claudication, and (3) critical ischemia of the hand. The majority of these patients have a cervical rib, which may or may not be fused to the 1st rib and is most commonly posterior to the subclavian artery. The etiology is chronic repetitive injury to the subclavian artery as it exits the thoracic outlet. This injury may cause subclavian artery stenosis but more commonly leads to ectasia or a true aneurysm.

In asymptomatic patients, a pulsatile mass or supraclavicular bruit can be detected on physical examination.

Arm claudication is caused by areas of stenosis which may be static due to long-standing repetitive injury or dynamic, occurring only with arm abduction or extension.

Critical ischemia is due to emboli of fibrinoplatelet aggregates that originate from an ulcerated mural thrombus in the aneurysmal segment.

PREOPERATIVE EVALUATION AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

In young patients (<40 years of age) with a classic presentation of neurogenic TOS, there is no need for extensive preoperative testing.

Older patients and those with a history of neck trauma should undergo magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to rule out cervical disc pathology.

Preoperative physical therapy should be attempted for at least 8 weeks in patients with a diagnosis of neurogenic TOS. The aims of therapy are to improve posture and achieve greater range of motion. Patients with persistent symptoms of neurogenic TOS despite 8 weeks of physical therapy merit surgical intervention. At least 60% of patients will improve with physical therapy and lifestyle alterations.

A radiographically guided anterior scalene block with local anesthetic (lidocaine) injection may provide a few hours of symptomatic relief. Patients with suspected neurogenic TOS often present with a wide constellation of physical complaints, not all of which are directly attributable to the disorder. A scalene block not only helps confirm the diagnosis but also simulates the expected postoperative result, especially in older patients.3 This provides the patient and the surgeon reassurance that surgical intervention will be of benefit and demonstrates which symptoms can be reliably expected to improve.

As an alternative to surgical therapy, patients can then opt for a Botox (Allergan, Irvine, CA) injection. The Botox takes an average of 2 weeks to work and may be repeated. This may provide symptomatic relief for 2 to 3 months, allowing participation in physical therapy. However, not all TOS patients respond to Botox. This practice is especially helpful in patients who have had cervical spine fusions or shoulder operations as they can strengthen the muscles of their neck and back, which may alleviate the TOS symptoms.

Plain film chest x-ray is recommended for all patients undergoing surgical intervention for TOS to rule out a cervical rib.

Nerve conduction studies are typically normal in neurogenic TOS but may be useful in ruling out nerve compression such as carpal tunnel or cubital compression syndrome.

Duplex ultrasonography is the initial diagnostic modality to confirm pathology in patients with arterial TOS. Although useful to confirm axillosubclavian vein thrombosis in patients with suspected venous TOS, venography often supplants it for both diagnostic and therapeutic reasons. Lastly, venous TOS is frequently bilateral.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Surgical Approach

Patients with a diagnosis of TOS who are appropriate surgical candidates should undergo surgical decompression of the thoracic outlet.

The optimal approach should be individualized depending on the patient’s symptoms, anatomy, and surgeon’s experience.

The transaxillary approach is preferred by many surgeons because of its relative ease, low-risk profile, and documented improvement in patients’ quality of life.4,5 This approach effectively decompresses the thoracic outlet and is generally reserved for patients with neurogenic or venous TOS.

If vessel reconstruction is anticipated, a different approach should be considered as the transaxillary approach limits vessel exposure.

Surgical Anatomy

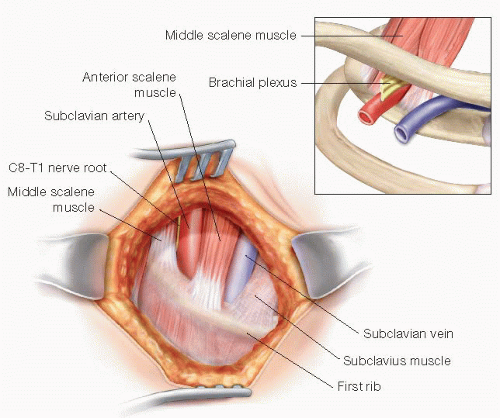

The subclavian artery and the five nerve roots (C5-T1) to the brachial plexus are located within the thoracic outlet. The artery courses anterior to the brachial plexus nerve roots and exits the mediastinum in its course over the 1st rib behind the posterior border of the anterior scalene muscle. The cervical spine nerve roots join to form the initial trunks of the brachial plexus within the thoracic outlet and are located posterior to the subclavian artery. Subsequent merging and branching of these trunks into divisions, cords, and terminal nerves occurs outside the thoracic outlet.

Other significant nerves within the thoracic outlet are the phrenic and long thoracic nerves.

The phrenic nerve receives fibers from C3-C5 and courses in a descending oblique direction from the lateral to the medial edge of the middle portion of the anterior scalene muscle. The phrenic nerve approaches the mediastinum posterior to the subclavian vein.

The long thoracic nerve, composed of nerve fibers from C5-C7, passes through the center of the middle scalene muscle and heads toward the chest wall to innervate the serratus anterior muscle.

The subclavian vein technically does not course through the thoracic outlet. It passes over the 1st rib anterior to the anterior scalene muscle. However, the middle segment of the vein remains susceptible to compression between the anteromedial 1st rib, clavicle, and the subclavius muscle (FIG 1). Hypertrophy of the subclavius muscle and tendon may occur in athletes and is often implicated in venous TOS.

Several anatomic anomalies are relevant to the surgeon, as they predispose patients to the development of TOS.

The most common is a cervical rib, and a preoperative chest radiograph is adequate for its detection. When present, cervical ribs appear as extensions of the transverse process of C7. Cervical ribs may be complete or partial, with the anterior end attaching to the 1st rib or floating freely. Additionally, the anterior end may be fibrous and not calcified and thus not completely visualized on chest radiograph. By rigidly confining the thoracic outlet, cervical ribs render the neurovascular structures more prone to compression. Although present in the general population with an incidence of 0.5% to 1%, they are found in 5% to 10% of all TOS patients.

A prominent C7 transverse process or bifid 1st rib is also associated with TOS.

Positioning

General endotracheal anesthesia is induced and sequential compression devices are applied.

FIG 1 • Right-sided thoracic outlet anatomy from the surgeon’s perspective as viewed through the operative field in a transaxillary approach. Inset, normal anatomic relationships of important thoracic outlet structures.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access