Neuroendocrine Tumors of the Gastrointestinal Tract, Appendix, Gallbladder, and Extrahepatic Biliary Tract

Shilpa Rungta

Sudha R. Kini

This chapter covers the neuroendocrine neoplasms arising in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, the appendix, the gallbladder, and extrahepatic biliary ducts.

NEUROENDOCRINE NEOPLASMS OF THE GASTROINTESTINAL TRACT

Neuroendocrine neoplasms of the GI tract are uncommon. Their annual incidence is stated to be 2.0/100,000 for men and 2.4/100,000 for women in the United States. GI neuroendocrine neoplasms present a spectrum of lesions from low-grade carcinomas (carcinoids) to high-grade carcinomas (small cell carcinoma), the former accounting for the majority. They arise anywhere in the GI tract from esophagus to anus.

The classification of GI neuroendocrine neoplasms has undergone several modifications over the years. World Health Organization (WHO) in 2010 revisited the nomenclature and classification of neuroendocrine neoplasms of the digestive system, taking into account the following concepts as proposed by the European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (ENTS): (1) tumor heterogeneity, that is, tumors differ according to the site of origin; (2) tumor differentiation, that is, tumors differ according to tumor cell differentiation status; and (3) malignancy, that is, longterm follow-up indicates that neuroendocrine tumors as a category are malignant. The proposed grading was based on proliferation and offered three tiers (G1, G2, G3) with the following definitions of mitotic count and Ki 67 index: G1—mitotic count < 2 per 10 high power fields (HPFs) and/or 2% Ki 67 index; G2—mitotic count 2 to 20 per 10 HPFs and/or 3% to 20% Ki 67 index; and G3—mitotic count > 20 per 10 HPFs and/or >20% Ki 67 index. The classification is basically a two-tier system that includes two groups: neuroendocrine tumors and neuroendocrine carcinomas. Grading is combined with a site-specific staging system to improve prognostic strength (see Appendixes I and II).

Neuroendocrine neoplasms are exceedingly rare in esophagus (0.8% to 3.1% of esophageal malignancies) and the anus. Most reported neuroendocrine carcinomas of the esophagus are all poorly differentiated or small cell carcinomas. Their cytologic documentation is rare and is based on endoscopic esophageal washings, a procedure that is currently not utilized.

NEUROENDOCRINE TUMORS (CARCINOID) OF THE GASTROINTESTINAL TRACT

INTRODUCTION

Neuroendocrine tumors or carcinoid tumors arise in different parts of the GI tract with varying frequency. They also present different demographics, arise from different embryonic segments, secrete different hormones, and present different morphologic patterns and biologic behavior.

Small nonfunctioning tumors are usually clinically silent and may be discovered only at autopsy or following resection for other indications. Symptoms are attributable to local tumor effects caused by local adhesions or fibrosis giving rise to abdominal pain or small bowel obstruction or to secretion of bioactive substances such as serotonin, histamine, or gastrin. The carcinoid syndrome (cutaneous flushing of upper chest, neck, and face; gut hypermotility

with diarrhea) occurs in <10% of patients. Diagnostic strategies for patients suspected of having GI neuroendocrine neoplasms include biochemical testing for urinary 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid or serum testing for increased chromogranin A levels, followed by localization of the tumor by OctreoScan scintigraphy, positron emission tomography (PET), or other radiographic imaging techniques.

with diarrhea) occurs in <10% of patients. Diagnostic strategies for patients suspected of having GI neuroendocrine neoplasms include biochemical testing for urinary 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid or serum testing for increased chromogranin A levels, followed by localization of the tumor by OctreoScan scintigraphy, positron emission tomography (PET), or other radiographic imaging techniques.

TABLE 4.1 GASTROINTESTINAL NEUROENDOCRINE TUMORS (CARCINOID) OF THE GASTROINTESTINAL TRACT | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Grossly, these tumors are usually submucosal or can present as thickened muscularis propria in the area of the tumor as a result of secretion of trophic factors by the tumor cells. They may also present as annular strictures as a result of dense fibrosis associated with the tumor. Rarely, ischemic injury secondary to vascular sclerosis can be associated with small bowel tumors. Multicentricity is common and is site related; gastric and jejunoileal tumors (33%) are more commonly multiple, whereas multiplicity is rare with colonic or appendiceal neuroendocrine tumors.

Microscopically, most GI neuroendocrine tumors are well-differentiated or low-grade carcinomas (carcinoid tumors), composed of uniform cells with round to oval nuclei with finely granular salt-pepper chromatin and inconspicuous nucleoli. Their growth pattern varies from solid sheets, insular or nests, or trabecular.

In general, GI neuroendocrine neoplasms are divided into three categories based on their embryologic derivations: foregut for stomach, duodenum, and proximal jejunum; midgut for distal jejunum, ileum, appendix, and upper colon; and hindgut for distal colon and rectum. Each of these has specific characteristics that are site specific (Table 4.1) as classified by Williams and Sandler (1963).

It is extremely important to appreciate the fact that unlike neuroendocrine tumors occurring at most other body sites, a primary cytologic diagnosis of most GI neuroendocrine neoplasms is rarely made. Reasons are several. Gastric lesions are usually biopsied for histologic diagnosis. Brushings as a diagnostic procedure for cytologic interpretation is generally not favored by the clinicians except for duodenal lesions that can be approached via endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) guidance for aspiration biopsies or via endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) for brushings. The lesions of the jejunum, ileum, and appendix are usually diagnosed incidentally because of their metastases to lymph nodes, liver, or peritoneal cavities. Same holds true for colonic and rectal neoplasms.

NEUROENDOCRINE TUMORS (CARCINOID) OF THE STOMACH (FOREGUT)

Majority of the gastric neuroendocrine tumors of the stomach are well-differentiated or low-grade carcinomas (carcinoid tumors). They are rare lesions, accounting for

<2% of all carcinoids and 9% to 11% of all GI carcinoid tumors. Three types of gastric neuroendocrine tumors are recognized.

<2% of all carcinoids and 9% to 11% of all GI carcinoid tumors. Three types of gastric neuroendocrine tumors are recognized.

Type I is the most frequent type, comprising 70% to 80% of all the cases, and is associated with chronic atrophic (autoimmune) gastritis, hypergastrinemia with multiple small fundic tumors, limited to mucosa and submucosa and enterochromaffin-like (ECL)-cell hyperplasia.

Type II represents 6% of the gastric carcinoid tumors and occurs in association with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN 1) with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome and hypergastrinemia.

Type III represents 13% of gastric carcinoids and usually affects males, mean age being 55 years. These are sporadic and have no association with chronic atrophic (autoimmune) gastritis, MEN, or Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. These tumors are usually larger and may be infiltrative and metastasize to the lymph nodes and liver.

The prognosis is generally good for Type I and Type II. The sporadic Type III presents an aggressive behavior.

GROSS AND HISTOLOGIC FEATURES

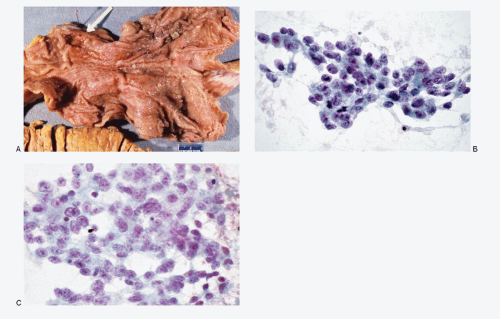

Grossly, Type I and Type II gastric neuroendocrine tumors tend to be well circumscribed, multiple, small, <1 cm, and located in submucosa of the fundus and body. The sporadic Type III gastric neuroendocrine neoplasms tend to be solitary (Fig. 4.1A), larger with high risk for lymph node and liver metastasis.

Histologically, gastric carcinoids present a trabecular growth pattern characteristic for foregut-derived GI segment. The neoplastic cells are uniform, small, and cuboidal with high N/C ratios. Their nuclei present typical salt-pepper chromatin. These tumors may exhibit marked pleomorphism with prominent nucleoli. The tumor may infiltrate the underlying muscularis.

CYTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES

Cytologic diagnosis is not generally made since endoscopic gastric brushings as a diagnostic procedure are not generally recommended or performed. The cytologic

diagnosis is made on metastatic lesions involving liver or lymph nodes by fine needle aspiration biopsies. The neoplastic cells exhibit a wide range of morphology, from uniform, small, to medium-sized cells with variable N/C ratios and nuclei with coarsely granular chromatin and with or without multiple nucleoli (Fig. 4.1B,C).

diagnosis is made on metastatic lesions involving liver or lymph nodes by fine needle aspiration biopsies. The neoplastic cells exhibit a wide range of morphology, from uniform, small, to medium-sized cells with variable N/C ratios and nuclei with coarsely granular chromatin and with or without multiple nucleoli (Fig. 4.1B,C).

HISTOCHEMISTRY

The cells of gastric neuroendocrine tumors (carcinoids) are argyrophilic.

IMMUNOPROFILE

The cells of gastric neuroendocrine tumors (carcinoids) are reactive to pan neuroendocrine markers and cytokeratin.

ULTRASTRUCTURE

Ultrastructural findings include the presence of neurose-cretory granules.

NEUROENDOCRINE TUMORS (CARCINOIDS) OF THE DUODENUM AND PROXIMAL JEJUNUM (FOREGUT)

The incidence of duodenal and upper jejunal neuroendocrine tumors in relation to all GI neuroendocrine tumors ranges from 3% to 22% with a slight male predominance with the male:female ratio being 1.5:1. Usually, patients in fifth and sixth decades are affected. Four distinct histologic types are recognized that include (1) gastrinomas, (2) somatostatinomas, (3) nonfunctioning serotonin- and calcitonin-producing tumors, and (4) gangliocytic paragangliomas. Clinical history and laboratory data are of considerable help in the diagnosis as approximately 25% of gastrinomas are associated with MEN 1 (G-cell hyperplasia), the remainder 75% occurring sporadically (usually solitary). These tumors are associated with increased gastrin levels and two-thirds of the patients present with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. Sixty to seventy percent of these tumors occur in the first portion of the duodenum. The important prognostic factor to be considered is that even though small in size, these duodenal tumors have an aggressive behavior with early lymph node metastasis and therefore are considered malignant regardless of other features.

Somatostatinomas comprise 15% to -20% of the duodenal neuroendocrine tumors and are predominantly located in the periampullary region. Around one-third of the cases are associated with Type 1 neurofibromatosis (von Recklinghausen disease) and some with MEN 1. Patients with duodenal somatostatinomas rarely present with the somatostatin syndrome (diabetes, achlorhydria, cholelithiasis, and diarrhea), which is clinically observed in patients with pancreatic somatostatinomas. The duodenal/periampullary tumors are unrelated to the pancreatic ones.

Gangliocytic paraganglioma is an unusual tumor presenting features of paraganglioma, carcinoid tumor, and ganglioneuroma. It almost always occurs in the second part of the duodenum. These tumors are often large up to 7 cm. Histologically, the neoplasm consists of epithelioid areas similar to those seen in paraganglioma, with ribbon-like, and trabecular pattern of carcinoid tumors that are surrounded by delicate network of Schwann cells and nerve axons. Scattered, variably differentiated ganglion cells are present within Schwannian stroma. These tumors are uncommon and there is no documentation of cytologic features.

CYTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES

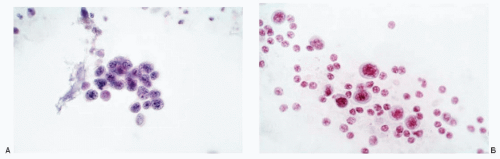

Neuroendocrine neoplasms of the duodenum are more accessible to the endoscopic procedures. Cytologic diagnosis via EUS-guided fine needle biopsy or by brushings via ERCP can be rendered (Figs. 4.4 and 4.5). The cytologic preparations demonstrate high cellularity with malignant cell population represented by uniform small round to cuboidal cells, occurring singly with a dispersed pattern or in loosely cohesive groups and in syncytial tissue fragments. The tissue fragments may present a trabecular pattern with or without branching. The neoplastic cells have poorly defined cell borders and scant cytoplasm with high N/C ratios. Their nuclei

contain coarsely granular, salt-pepper chromatin, and inconspicuous nucleoli.

contain coarsely granular, salt-pepper chromatin, and inconspicuous nucleoli.

Differential Diagnosis of Gastric Neuroendocrine Tumors (Carcinoids) (Figs. 4.2 and 4.3)

Fig. 4.2: A: Gastric brushings showing adenocarcinoma cells that are small in size and have scant cytoplasm. These cells can be misinterpreted as neuroendocrine tumor. B: Another case of gastric adenocarcinoma depicting single cells in brushings. These may be mistaken for a neuroendocrine tumor.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|