Nephrology

Tomas Berl

Isaac Teitelbaum

Acute Renal Failure

Under what circumstances is serum creatinine a reasonable marker for glomerular filtration rate (GFR)? How is the creatinine clearance estimated from the serum creatinine?

What clinical findings most commonly suggest the presence of acute renal failure?

What processes need to be considered when attempting to ascertain the cause of acute renal failure?

What are the most common causes of acute renal failure in hospitalized patients and in outpatients?

What are the urinary findings that assist in differentiating prerenal azotemia from intrarenal acute renal failure?

What are the complications of acute renal failure?

Discussion

Under what circumstances is serum creatinine a reasonable marker for GFR? How is the creatinine clearance estimated from the serum creatinine?

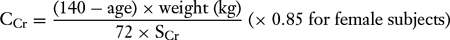

The serum creatinine is a reasonable marker for creatinine clearance and GFR only in the steady state, that is, when the serum creatinine is neither increasing nor decreasing. In the steady state, the creatinine clearance (CCr) may be estimated from the serum creatinine (SCr) by the Cockroft-Gault equation:

Another equation derived as a result of the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) study has recently been validated as a more reliable predictor of GFR in some circumstances, such as chronic kidney diseases:

A GFR calculator utilizing this equation may be found at the website, http://www.nephron.com/cgi-bin/MDRD.cgi, and is also available on many “handheld” devices.

What clinical findings most commonly suggest the presence of acute renal failure?

A rise in the blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and serum creatinine levels and development of oliguria (<400 mL per day) are the common clinical findings that suggest the presence of acute renal failure. However, the absence of oliguria does not exclude acute renal failure because the process may also be nonoliguric. In fact, 20% to 30% of patients with acute renal failure are nonoliguric (>400 mL per day).

What processes need to be considered when attempting to ascertain the cause of acute renal failure?

In patients with acute renal failure, prerenal, postrenal, and intrarenal processes need to be considered. The respective causes of prerenal and postrenal azotemia as well as intrinsic renal disease are listed in Tables 9-1,9-2,9-3.

What are the most common causes of acute renal failure in hospitalized patients and in outpatients?

In hospitalized patients, the most common cause of acute renal failure (45%) is acute tubular necrosis, followed by prerenal azotemia and obstruction. Glomerulonephritis, vasculitis, interstitial nephritis, and atheroembolic

disease comprise most of the remaining causes. In contrast, acute renal failure in outpatients is most commonly due to prerenal azotemia (70%), followed by obstruction. Drug nephrotoxicity [e.g., aminoglycosides, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)] accounts for most of the remaining cases.

Table 9-1 Causes of Prerenal Azotemia

- Reduced extracellular and intravascular volume

- Gastrointestinal losses (vomiting, diarrhea, nasogastric suction)

- Dehydration

- Burns

- Hemorrhage

- Gastrointestinal losses (vomiting, diarrhea, nasogastric suction)

- Reduced intravascular volume but increased extracellular volume

- Cirrhosis

- Nephrotic syndrome

- Congestive heart failure—cardiogenic shock

- Third-space fluid accumulation (postoperative from abdominal surgery, severe pancreatitis, peritonitis)

- Cirrhosis

- Hemodynamically mediated acute renal failure

- Anesthesia

- Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory agents (due to renal prostaglandin inhibition)

- Inhibitors of the renin-angiotensin system (due to a decrease in efferent arteriolar tone)

- Hepatorenal syndrome

- Anesthesia

- Vasoconstrictor agents

- Calcineurin inhibitors

- Contrast agents

- Calcineurin inhibitors

- Reduced extracellular and intravascular volume

What are the urinary findings that assist in differentiating prerenal azotemia from intrarenal acute renal failure?

The urinary findings that can be used to help differentiate between prerenal azotemia and intrarenal acute renal failure are listed in Table 9-4.

What are the complications of acute renal failure?

The various complications of acute renal failure are listed by category in Table 9-5.

Case

A 65-year-old diabetic woman presents to the emergency room with right upper quadrant pain that radiates around to the back, together with nausea, vomiting, anorexia, lightheadedness, and a diminished urine output during the last 24 hours. She has no previous history of renal dysfunction. Her temperature is 37.5°C (99.5°F); supine, her blood pressure is 110/70 mm Hg and pulse is 80 beats per minute; upright, her blood pressure is 85/60 mm Hg and pulse is 110 beats per minute. The physical examination findings are otherwise remarkable for the presence of decreased skin turgor, dry mucosal

membranes, flat neck veins, and absence of axillary sweat. Her lungs are clear and the cardiac findings are normal. There is exquisite right upper quadrant abdominal tenderness that worsens with inspiration, her stool is guaiac negative, and no edema is noted. Neurologic examination reveals nonfocal findings.

membranes, flat neck veins, and absence of axillary sweat. Her lungs are clear and the cardiac findings are normal. There is exquisite right upper quadrant abdominal tenderness that worsens with inspiration, her stool is guaiac negative, and no edema is noted. Neurologic examination reveals nonfocal findings.

Table 9-2 Causes of Postrenal Azotemia | |

|---|---|

|

The following laboratory data are obtained: hematocrit, 50.2%; white blood cell count, 19,500/mm3 with 82% polymorphonuclear leukocytes, 16% band forms, and 2% lymphocytes; platelets, 312,000/mm3; sodium, 146 mEq/L; potassium, 4.1 mEq/L; chloride, 111 mEq/L; carbon dioxide, 22 mEq/L; glucose, 195 mg/dL; BUN, 35 mg/dL; creatinine, 1.6 mg/dL; total bilirubin, 1.8 mg/dL; alkaline phosphatase, 289 IU; and aspartate aminotransferase (AST), 35 U/L.

Urinalysis reveals a pH of 5, a specific gravity of 1.028; 1+ glucose, trace ketones, occasional nonpigmented granular casts, and no cellular casts or bacteria. The urine sodium level is 10 mEq/L and the urine creatinine level is 80 mg/dL.

Abdominal ultrasonography reveals the existence of gallstones and dilatation of the biliary tree. The kidneys measure 11 cm but exhibit no hydronephrosis or increased echogenicity.

While in the emergency room, the patient’s fever spikes to 39°C (102.2°F), which is accompanied by 3 minutes of rigors and a decrease in blood pressure to

80/50 mm Hg. She is admitted to the hospital with a diagnosis of acute cholecystitis for the purpose of observation and eventual cholecystectomy. She is given gentamicin [2 mg/kg intravenously (IV)] and ampicillin (2 g IV every 6 hours). Her urine output over 12 hours is 100 mL. The next morning, the following laboratory values are reported: sodium, 140 mEq/L; potassium, 5 mEq/L; chloride, 100 mEq/L; carbon dioxide, 15 mEq/L; glucose, 130 mg/dL; BUN, 40 mg/dL; and creatinine, 2.5 mg/dL. Urinalysis now reveals a pH of 5 and a specific gravity of 1.010 with occasional renal tubular epithelial cells and a rare, muddy-brown granular cast. The urine sodium level is 80 mEq/L and the urine creatinine level is 40 mg/dL. Blood cultures are positive for a gram-negative bacillus.

80/50 mm Hg. She is admitted to the hospital with a diagnosis of acute cholecystitis for the purpose of observation and eventual cholecystectomy. She is given gentamicin [2 mg/kg intravenously (IV)] and ampicillin (2 g IV every 6 hours). Her urine output over 12 hours is 100 mL. The next morning, the following laboratory values are reported: sodium, 140 mEq/L; potassium, 5 mEq/L; chloride, 100 mEq/L; carbon dioxide, 15 mEq/L; glucose, 130 mg/dL; BUN, 40 mg/dL; and creatinine, 2.5 mg/dL. Urinalysis now reveals a pH of 5 and a specific gravity of 1.010 with occasional renal tubular epithelial cells and a rare, muddy-brown granular cast. The urine sodium level is 80 mEq/L and the urine creatinine level is 40 mg/dL. Blood cultures are positive for a gram-negative bacillus.

Table 9-3 Causes of Intrarenal Acute Renal Failure | |

|---|---|

|

Table 9-4 Urine Findings in Prerenal Azotemia and Acute Renal Failure | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Table 9-5 Complications of Acute Renal Failure | ||

|---|---|---|

|

During the next 3 days, the patient remains oliguric and mild congestive heart failure develops. The BUN and creatinine levels rise steadily to 100 and 5.5 mg/dL, respectively.

At the time of arrival in the emergency room, what is the most likely explanation for this patient’s acute renal dysfunction, and why?

At the time of the patient’s arrival in the emergency room, what treatment would you prescribe, and why?

What is the cause of the continuing rise in the serum creatinine level after the patient is admitted to the hospital, and why?

What is the role for diuretics in this patient, and what is the proper dosage?

What is the appropriate approach to fluid management when the patient becomes oliguric?

What are the indications for acute dialysis in acute renal failure, and what alternative extracorporeal procedures could be considered?

Case Discussion

At the time of arrival in the emergency room, what is the most likely explanation for this patient’s acute renal dysfunction, and why?

There is no evidence for a postrenal cause of the acute renal failure in this patient, given the renal ultrasound study showing no obstruction. This leaves prerenal and intrarenal causes as the source of the acute renal failure. The history and physical examination findings suggest prerenal azotemia stemming from volume depletion. The laboratory data that corroborate this diagnosis include a BUN–creatinine ratio that exceeds 20 and a fractional extraction of sodium (FENa) of 0.13%. The FENa is calculated as follows: UNa/PNa ÷ UCr/PCr × 100% = 10/146 ÷ 80/1.6 × 100% = 0.13%, where UNa and PNa are the urine and serum sodium levels, respectively, and UCr and PCr are the urine and serum levels of creatinine, respectively. In the setting of oliguria (<400 mL of urine per day), an FENa of less than 1% implies prerenal azotemia, whereas an FENa of greater than 2% implies an intrarenal process. In patients who are volume contracted due to diuretic use, the FENa is often elevated. In such patients the fractional excretion of urea (FEurea) may be more useful, calculated as Uurea/Purea ÷ UCr/PCr × 100. A value of less than 35% suggests prerenal azotemia.

At the time of the patient’s arrival in the emergency room, what treatment would you prescribe, and why?

In this clinical setting, repletion of the extracellular fluid volume is the most critical element of therapy. This can be accomplished by the administration of either normal saline or lactated Ringer’s solution; 250 to 500 mL can be given rapidly over 1 to 2 hours. These solutions, which are devoid of colloid, distribute in both intravascular and extravascular spaces. Fluid infusion should be continued until the blood pressure changes are no longer evident and a euvolemic state has been restored. This will also be accompanied by the reappearance of sodium in the urine. In the setting of prerenal azotemia, this maneuver should promptly return renal function to baseline.

What is the cause of the continuing rise in the serum creatinine level after the patient is admitted to the hospital, and why?

After she is admitted to the hospital, the patient’s clinical picture becomes more consistent with an intrarenal cause of acute renal failure, such as acute tubular necrosis. This is supported by the presence of tubular epithelial cells and brown granular casts in the urine. In addition, both the decrement in the UCr/PCr to 16 and the increase in the FENa to 3.57% strongly support this diagnosis. As to the cause of the intrarenal injury itself, gram-negative sepsis appears to be the most likely culprit. Aminoglycosides can also cause acute renal failure; however, this patient received only one dose of the antibiotic and, more commonly, the associated renal failure is nonoliguric. Ampicillin can cause acute interstitial nephritis, which has been reported for a number of antibiotics. The urinalysis would be expected to show white blood cells, red blood cells, white blood cell casts, and eosinophils.

What is the role for diuretics in this patient, and what is the proper dosage?

Diuretics have been used in an attempt to convert oliguric patients with acute renal failure to a nonoliguric state, which is associated with a better outcome and simpler fluid management. Whether this “conversion” truly alters the prognosis has

not been settled. Diuretics can play a major role in the treatment of fluid overload that accompanies the patient’s diminished urine output. Because loop diuretics need to reach the luminal membrane in this setting, very high doses are required (240 to 300 mg IV of furosemide or 8 to 12 mg IV of bumetanide). Doses higher than these have been used, but are not associated with an improved outcome and can cause permanent ototoxicity.

What is the appropriate approach to fluid management when the patient becomes oliguric?

When a patient is oliguric (urine volume ≤400 mL), fluid restriction is needed and intake should not exceed 1 L because daily insensible losses are estimated to be between 500 and 700 mL. Likewise, sodium and potassium restriction is necessary. Therefore, the administration of 1 L of 0.5 N NaCl (i.e., approximately 75 mEq of sodium) without potassium supplementation is likely to prevent expansion of the extracellular fluid volume, hyponatremia, and hyperkalemia. If the episode of acute renal failure is more prolonged, nutritional support is also important.

What are the indications for acute dialysis in acute renal failure, and what alternative extracorporeal procedures could be considered?

Dialysis is undertaken whenever any of the complications of acute renal failure ensue. These are listed in Table 9-5. Most commonly, dialysis is instituted for the management of fluid overload that is refractory to diuretic therapy, hyperkalemia that is resistant to therapy, or metabolic acidosis that cannot be adequately treated with bicarbonate. In oliguric, catabolic patients, dialysis has also been used to prevent rather than treat uremic symptoms, the so-called “prophylactic dialysis.” Continuous venovenous hemofiltration (CVVH) and continuous venovenous hemodialysis (HD) are alternatives to intermittent HD, and are being used increasingly.

Suggested Readings

Edelstein CL, Schrier RW. Acute renal failure: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. In: Schrier RW, ed. Renal and electrolyte disorders, 6th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2003: 401.

Kieran N, Brady HR. Clinical evaluation, management, and outcome of acute renal failure. In: Johnson R, Feehally J, eds. Comprehensive clinical nephrology, 2nd ed. Mosby, 2003.

Metabolic Acidosis

What is the definition of metabolic acidosis?

What compensatory mechanism is triggered by metabolic acidosis?

How is the anion gap calculated, and how is it helpful in evaluating metabolic acidosis?

What are the causes of a metabolic acidosis with an increased anion gap, and what is the anion responsible for the increased anion gap?

How is the osmolar gap calculated, and how is this value useful in evaluating patients with a metabolic acidosis?

What are the causes of a metabolic acidosis with a normal anion gap?

What is urinary anion gap (UAG) and in what circumstances is it useful?

What is the difference between proximal and distal renal tubular acidosis (RTA), and how are these two forms of RTA differentiated?

Discussion

What is the definition of metabolic acidosis?

Metabolic acidosis is a disorder that results from either the addition of hydrogen ion or the loss of bicarbonate, which, if unopposed, results in acidemia. However, metabolic acidosis is not defined either as a decrement in the serum bicarbonate level or as any given systemic arterial pH because, in the setting of mixed acid–base disorders. The serum bicarbonate level or pH, or both, may be normal or even elevated despite the presence of metabolic acidosis.

What compensatory mechanism is triggered by metabolic acidosis?

When metabolic acidosis develops, the decrease in pH activates carotid chemoreceptors and central nervous system receptors to stimulate ventilation. The increase in the minute ventilation lowers the partial pressure of carbon dioxide (Pco2), thereby returning the pH toward normal.

How is anion gap calculated, and how is it helpful in evaluating metabolic acidosis?

Metabolic acidosis is broadly classified on the basis of the presence or absence of an increased anion gap. The anion gap (in millimoles per liter) is calculated using the following formula: plasma sodium – (plasma chloride + plasma bicarbonate). In most laboratories, a normal anion gap is considered to be 12 ± 2 mmol/L. A normal anion gap metabolic acidosis results from either the addition of hydrochloric acid or the loss of bicarbonate with the concomitant retention of chloride. Because chloride is retained and is included in the calculation, the anion gap metabolic acidosis is maintained in the normal range. An increased anion gap results from the addition of an exogenous or endogenous acid. The anions produced by these acids are not measured and chloride is not retained. The anion gap increases because bicarbonate is consumed to buffer the organic acid. For example, organic anion + H+ + NaHCO3– → H2O + CO2 + Na organic anion + organic acid. Because the organic anion is not measured or included in the calculation, the anion gap increases.

What are the causes of a metabolic acidosis with an increased anion gap, and what is the anion responsible for the increased anion gap?

The various causes of metabolic acidosis with an increased anion gap are listed in Table 9-6.

How is the osmolar gap calculated, and how is this value useful in evaluating patients with a metabolic acidosis?

The plasma osmolality is calculated using the following formula: Calculated osmolality = 2[Na] + [glucose]/18 + [BUN]/2.8 + [ethanol]/4.6. The osmolar gap is equal to the measured osmolality minus the calculated osmolality. A normal osmolar gap is less than 10 mOsm/kg. When the osmolar

gap is elevated in an acidemic patient, ethylene glycol or methanol intoxication must be strongly suspected.

Table 9-6 Causes of Metabolic Acidosis with an Increased Anion Gap

Cause

Anion

Increased acid production

Diabetic ketoacidosis

BHB, AcAc

Lactic acidosis

Lactate, pyruvate

Starvation

—

Alcoholic ketoacidosis

BHB > AcAc

Nonketotic hyperosmolar coma

—

Inborn errors of metabolism

—

Ingestion of acid-generating toxic substances

Salicylate overdose (>30 mg/dL)

Variety

Methanol ingestion

Formate, lactate

Ethylene glycol ingestion

Lactate, glycolate, oxalate

Solvent inhalation

—

Failure of acid excretion

Acute renal failure

Variety, SO4, PO4

Chronic renal failure

—

BHB, betahydroxybutyrate; AcAc, acetoacetate.

What are the causes of a metabolic acidosis with a normal anion gap?

The causes of metabolic acidosis with a normal anion gap are listed in Table 9-7.

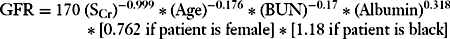

What is UAG and in what circumstances is it useful?

On occasion, the UAG may help distinguish gastrointestinal loss from renal loss of HCO3– as the cause of hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis:

The UAG is an estimate of the urinary ammonium that is elevated in gastrointestinal HCO3– loss but low in distal RTA. UAG is a negative value if urine ammonium is high (as in diarrhea; average, -20 mEq/L), whereas it is positive if urine ammonium is low (as in distal RTA; average, +23 mEq/L).

What is the difference between proximal and distal RTA, and how are these two forms of RTA differentiated?

RTA is one of the common causes of metabolic acidosis with a normal anion gap. Proximal RTA results from a failure to resorb the normal amount of bicarbonate in the proximal tubule, whereas distal RTA results from a defect in hydrogen ion secretion in the distal tubule. These two forms of RTA can be differentiated by determining the urine pH during systemic acidosis. In proximal RTA, when the serum bicarbonate, and therefore the filtered

bicarbonate level, is lowered to one that allows for proximal reabsorption of all the filtered bicarbonate, the urine can be maximally acidified (pH <5.4) as there is no increased distal delivery of unreabsorbed bicarbonate. In contrast, in distal RTA, the urine cannot be maximally acidified (pH >5.4) independent of the serum bicarbonate concentration.

Table 9-7 The Causes of a Metabolic Acidosis with a Normal Anion Gap | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Case

A 29-year-old man has been hospitalized in the psychiatry service for 2 months because of depression. The patient leaves the hospital on a pass and, on returning, complains of abdominal pain and vomiting. Over the next several hours, he becomes more agitated and is then found in an unarousable state and posturing.

Physical examination reveals a temperature of 102°F (38.8°C), pulse of 102 beats per minute, respiratory rate of 35 breaths per minute, and blood pressure of 160/100 mm Hg. The patient is unresponsive to pain. Funduscopic findings are within normal limits. No odors are noted on his breath.

Laboratory findings reveal the following: sodium, 142 mEq/L; potassium, 4.7 mEq/L; chloride, 111 mEq/L; bicarbonate, 10 mmol/L; serum calcium, 9.4 mg/dL; BUN, 12 mg/dL; and creatinine, 1.3 mg/dL. Arterial blood gas measurements performed on room air show a pH of 7.2, PCO2 of 17 mm Hg, and partial pressure of oxygen (PO2) of 100 mm Hg.

What is this patient’s acid–base disturbance, and what are the possible causes?

Why is the patient tachypneic, and is the compensation appropriate?

What other tests or laboratory findings would be useful in making the specific diagnosis?

In this patient, the serum glucose level proves to be normal and no serum ketones are detected. The plasma osmolality is 347 mOsm/kg and the osmolar gap is calculated to be 51 mOsm/kg. With the new information yielded by these additional tests, what possible diagnoses still remain?

How would you proceed to determine which substance is responsible for this patient’s presentation?

How would you treat this patient?

Case Discussion

What is this patient’s acid–base disturbance, and what are the possible causes?

The patient has an acidemia because the pH is 7.2. This could result from either a metabolic or a respiratory acidosis. The combination of a low PCO2 and a low serum bicarbonate concentration confirms the presence of a metabolic acidosis. In addition, the anion gap is elevated. The most likely causes of a metabolic acidosis with an increased anion gap, as outlined in Table 9-6, include diabetic ketoacidosis, lactic acidosis, starvation, alcoholic ketoacidosis, salicylate overdose, methanol or ethylene glycol ingestion, and renal failure.

Why is the patient tachypneic, and is the compensation appropriate?

The patient is tachypneic as a compensatory response to the metabolic acidosis. If the patient were not tachypneic, the pH would be even lower and this would suggest an additional respiratory disorder. This patient is exhibiting an appropriate respiratory compensatory response. The serum bicarbonate level is decreased by 14 mmol/L from normal. Therefore, the PCO2 should be decreased by 14 to 21 mm Hg (Table 9-8). The patient has a PCO2 that is decreased by 21 mm Hg from normal, and this compensation is appropriate for the degree of metabolic acidosis involved. Table 9-8 summarizes the general expected compensatory responses to acid–base disorders.

What other tests or laboratory findings would be useful in making the specific diagnosis?

The patient clearly has a metabolic acidosis with an increased anion gap, but it is necessary to identify the specific cause with further testing. Initial tests that might elucidate the cause of the process include (a) the serum glucose level to determine whether hyperglycemia is present; (b) serum ketone levels to ascertain if acetoacetate is present; (c) serum salicylate and lactate levels to determine whether salicylate intoxication or lactic acidosis is present; and (d) serum osmolality to determine if the osmolar gap is elevated.

In this patient, the serum glucose level proves to be normal and no serum ketones are detected. The plasma osmolality is 347 mOsm/kg and the osmolar gap is calculated to be 51 mOsm/kg. With the new information yielded by these additional tests, what possible diagnoses still remain?

With this additional information, you know that the patient has metabolic acidosis with an increased anion and osmolar gap. This limits the possible diagnoses to either methanol or ethylene glycol ingestion.

How would you proceed to determine which substance is responsible for this patient’s presentation?

Table 9-8 Rules of Thumb for Bedside Interpretation of Acid-Base Disorders

- Metabolic acidosis

- Paco 2 should fall by1.0-1.5 × the fall in plasma [HCO3-]

- Metabolic alkalosis

- Paco 2 should rise by0.25-1.0 × the rise in plasma [HCO3-]

- Acute respiratory acidosis

- Plasma [HCO3 -] should rise by approximately 1 mmol/L for each 10-mm Hg increment in Paco 2 (± 3 mmol/L)

- Chronic respiratory acidosis

- Plasma [HCO3 -] should rise by approximately 4 mmol/L for each 10-mm Hg increment in Paco 2 (± 4 mmol/L)

- Acute respiratory alkalosis

- Plasma [HCO3 -] should fall by approximately 1 – 3 mmol/L for each 10-mm Hg decrement in Paco2, but usually not to<18 mmol/L

- Chronic respiratory alkalosis

- Plasma [HCO3 -] should fall by approximately 2 – 5mmol/L per 10-mm Hg decrement in Paco2, but usually not to<14 mmol/L

Paco2, arterial carbon dioxide tension; [HCO3 -], bicarbonate ion concentration.

From Shapiro JI, Kaehny WD. Pathogenesis and management of metabolic acidosis and alkalosis. In: Schrier RW, ed. Renal and electrolyte disorders, 6th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2003. Reprinted with permission.

To determine which substance is responsible for this patient’s presentation, both methanol and ethylene glycol levels should be assayed in the blood. In addition, the urine should be examined for the presence of calcium oxalate crystals, which are frequently present in the setting of ethylene glycol ingestion because of the metabolic conversion of the ethylene glycol to oxalate. In the setting of methanol intoxication, visual disturbances could ensue.

- Metabolic acidosis

How would you treat this patient?

The treatment of metabolic acidosis involves treating the underlying disorder. In acute metabolic acidosis, the rapid correction of pH through the administration of bicarbonate appears to produce derangements in cardiovascular function, probably caused by a paradoxical intracellular acidosis. The use of bicarbonate in this setting is therefore controversial. More specifically, two goals become important in a patient who has ingested ethylene glycol. The first is to inhibit the metabolism of ethylene glycol. Although ethylene glycol by itself is not a toxic substance, the metabolites produced by the liver are quite toxic and can precipitate acute renal failure and even cause death. Alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) is the enzyme responsible for the metabolism of ethylene glycol, and it can be competitively inhibited by ethanol. Fomepizole, a direct inhibitor of ADH has also been employed. Ethylene glycol ingestion is still most commonly treated by the infusion of ethanol. The second goal

is to remove the ethylene glycol from the body. Ethylene glycol is excreted very slowly by the kidneys and, if the blood level is very high, HD may become necessary to improve removal of this substance from the blood. A similar approach is used for methanol ingestion.

Suggested Readings

Palmer BF, Alpern RJ. Normal acid-base balance and metabolic acidosis. In: Johnson R, Feehally J, eds. Comprehensive clinical nephrology, 2nd ed. Mosby, 2003.

Shapiro JI, Kaehny WD. Pathogenesis and management of metabolic acidosis and alkalosis. In: Schrier RW, ed. Renal and electrolyte disorders, 6th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2003: 115.

Metabolic Alkalosis

What is the definition of metabolic alkalosis?

What are the processes involved in the generation of metabolic alkalosis?

What are the processes involved in the maintenance of metabolic alkalosis?

What are the two major categories of metabolic alkalosis, and what laboratory test is used to differentiate between the two?

What are the causes of NaCl-responsive metabolic alkalosis?

What are the causes of NaCl-resistant metabolic alkalosis?

What are the causes of metabolic alkalosis that are unclassified?

What is the compensatory mechanism that is stimulated by metabolic alkalosis?

Discussion

What is the definition of metabolic alkalosis?

Metabolic alkalosis is a disorder that results from either the loss of hydrogen ions or the addition of bicarbonate, which, if unopposed, results in alkalemia. Metabolic alkalosis is not defined either as an increment in the serum bicarbonate concentration or as a given systemic arterial pH because, in the setting of mixed acid–base disorders. The serum bicarbonate level or the pH, or both, could be either normal or even decreased in the presence of metabolic alkalosis.

What are the processes involved in the generation of metabolic alkalosis?

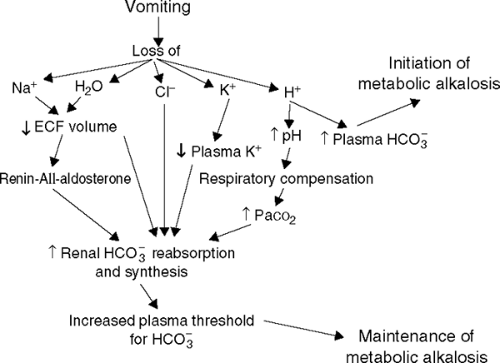

Pathophysiologically, the development of metabolic alkalosis involves two phases (see Fig. 9-1). The first involves the generation of metabolic alkalosis. As follows from the definition just given, metabolic alkalosis can be generated as a result of either a net loss of hydrogen ions from the extracellular fluid, most commonly from either the upper gastrointestinal tract or more rarely through the kidneys, or from the net addition of bicarbonate or substances that generate bicarbonate (e.g., lactate, citrate, and acetate). In addition, the

loss of fluid having high concentrations of chloride and low concentrations of bicarbonate, as occurs with diuretic use and certain gastrointestinal tract diseases such as villous adenoma, generates a metabolic alkalosis.

What are the processes involved in the maintenance of metabolic alkalosis?

The kidney provides the corrective response to metabolic alkalosis by excreting excess bicarbonate. When the serum bicarbonate level exceeds 28 mEq/L, the anion appears in the urine, thereby preventing a further increase in its concentration. The maintenance of alkalosis therefore requires an alteration in renal bicarbonate reabsorption. Several factors constrain the kidney’s ability to excrete bicarbonate and are important in the maintenance phase of metabolic alkalosis. Probably, the most important factor in this regard is extracellular fluid volume depletion, which serves to stimulate increased sodium resorption and bicarbonate reclamation in the proximal tubule. A decrement in GFR with a decrease in bicarbonate filtration contributes to the maintenance of the metabolic alkalosis. Another important factor in the maintenance of metabolic alkalosis is the chloride concentration. When the plasma bicarbonate concentration rises, the chloride concentration must fall. Because chloride is the only anion other than bicarbonate that can accompany sodium resorption, bicarbonate resorption is enhanced in its absence. Therefore, chloride must exist in sufficient quantity to allow for bicarbonate excretion. The hormone aldosterone stimulates the exchange of sodium reabsorption for hydrogen or potassium ion secretion in the distal tubule. With

the secretion of hydrogen ions, bicarbonate generation occurs in the plasma. Potassium ion depletion directly enhances bicarbonate reabsorption. An elevation in the Pco2 also stimulates bicarbonate reabsorption, and is important in the compensatory mechanism that keeps respiratory acidosis in check.

Table 9-9 Causes of NaCl-Responsive Metabolic Alkalosis

- Gastrointestinal disorders

- Vomiting

- Gastric drainage

- Villous adenoma of the colon

- Chloride diarrhea

- Vomiting

- Diuretic therapy

- Correction of chronic hypercapnia

- Cystic fibrosis

- Gastrointestinal disorders

What are the two major categories of metabolic alkalosis, and what laboratory test is used to differentiate between the two?

Metabolic alkalosis can be divided into two groups: NaCl responsive and NaCl resistant. The former is found in alkalemic patients who are volume depleted, and the latter in those with volume expansion. The most useful laboratory test for differentiating between the two groups is a spot urine chloride determination done before the initiation of therapy. In NaCl-responsive states, the urine chloride concentration is usually less than 20 mEq/L, and frequently even less than 10 mEq/L; in NaCl-resistant states, the urine chloride level exceeds 20 mEq/L. However, although metabolic alkalosis is routinely divided into these two categories, there are several disorders that are unclassified.

What are the causes of NaCl-responsive metabolic alkalosis?

The causes of NaCl-responsive metabolic alkalosis are listed in Table 9-9.

What are the causes of NaCl-resistant metabolic alkalosis?

The causes of NaCl-resistant metabolic alkalosis are listed in Table 9-10.

What are the causes of metabolic alkalosis that are unclassified?

The unclassified causes of metabolic alkalosis are listed in Table 9-11.

What is the compensatory mechanism that is stimulated by metabolic alkalosis?

When metabolic alkalosis develops, the alkalemia is sensed by chemoreceptors in the respiratory system. This leads to hypoventilation and an increase

in Pco2. As a general rule, the Δ Pco2 (mm Hg) = 0.25 – 1.0 M × [HCO3–] mEq/L, where Δ Pco2 is the change in the Pco2. However, this hypoventilatory response is not as efficient as the hyperventilatory responses that accompany a metabolic acidosis.

Table 9-10 Causes of NaCl-Resistant Metabolic Alkalosis | |

|---|---|

|

Table 9-11 Unclassified Causes of Metabolic Alkalosis | |

|---|---|

|

Case

A 25-year-old man with no previous medical history presents to the emergency room because of abdominal pain and severe vomiting of 2 days’ duration, during which time he has been unable to eat or drink. He is taking no medications.

Physical examination reveals the following: temperature, 37.6°C (99.68°F); pulse, 120 beats per minute; respiratory rate, 18 breaths per minute; and blood pressure, 120/80 mm Hg. Orthostatic changes in the pulse and blood pressure are found, and there is mild, diffuse abdominal tenderness.

The following laboratory findings are reported: sodium, 140 mEq/L; potassium, 3.4 mEq/L; chloride, 90 mEq/L; bicarbonate, 35 mmol/L; and creatinine, 1.5 mg/dL. Arterial blood gas measurements on room air reveal a pH of 7.55, PCO2 of 44 mm Hg, and PO2 of 77 mm Hg.

What acid–base disturbances are present in this patient?

What are the possible causes of this patient’s metabolic alkalosis, and what laboratory test might be useful to elucidate the nature of the cause?

What factors are responsible for the generation and maintenance of the metabolic alkalosis in this patient?

If the patient’s vomiting were to stop spontaneously, would the acid–base disturbance also resolve?

How would you treat this patient?

Case Discussion

What acid–base disturbances are present in this patient?

The patient is alkalemic (pH, 7.55). Therefore, either a metabolic alkalosis or a respiratory alkalosis, or both, exist. The serum bicarbonate level is elevated to 35 mEq/L, and this indicates a metabolic alkalosis. In the setting of a respiratory

alkalosis, the PCO2 would be decreased, which is not the case in this patient. In the setting of metabolic alkalosis, the expected respiratory compensation (hypoventilation) would increase the PCO2. Because the PCO2 of 44 mm Hg is an increased value, this further supports the presence of a simple metabolic alkalosis with appropriate respiratory compensation.

What are the possible causes of this patient’s metabolic alkalosis, and what laboratory test might be useful to elucidate the nature of the cause?

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree