Continuous Leadership Development

Communication is the key to action in building your team and calibrating their efforts toward meaningful, positive action. To ensure that your leadership style develops progressively and your effectiveness grows over time, start with the following strategies:

Get as diverse and as much feedback as possible on leadership effectiveness. Influences on your leadership style can be numerous and diverse; have family, peers, and trusted subordinates give you feedback on your leadership effectiveness. Get suggestions from all these individuals and try to incorporate any good ideas into your future efforts.

Give clear direction at all times to all staff members. Try to specify exactly what is expected and provide as much insight as appropriate on why something should be done. Sharing this information with employees can build trust and allow you to have two-way communication, which is important for a successful leader. Use appropriate follow-up methods to ensure that progress is being made and provide as much additional instruction as possible as employees strive to achieve their goals. Doing so enhances communication and trust, which will be the two most vital components to your success.

Give staff an appropriate amount of freedom. Assume that staff members know what they are doing vital vice until they prove otherwise. Providing too much direction or constraining performance can create the perception that you are unnecessarily overbearing or not trusting your staff. Closely monitor performance, provide inspiration, and measure goal attainment of all staff members.

Balance positive and negative information realistically. You must occasionally give your staff bad news. Provide this information on a timely basis, try to identify an upside (if possible), and deal with problems realistically. On these occasions, verbally stress your confidence that the group can handle adversity and rebound from negative circumstances. Strong leaders participate in adversity as much as in prosperity.

Try to keep perspectives on all issues. The true measure of leaders, in the opinion of many, is their reaction to things that are above and beyond the call of duty or beyond the norm. Try to maintain a balanced view of things, and exhibit the courage and strength necessary to handle tough situations.

Learn from every situation. Health care offers learning opportunities every day. Collect as much information as possible, process that information, and incorporate it into your leadership efforts. Remember that the best way to learn things is to ask appropriate questions. These may be questions that you ask yourself about what you have learned from a situation or questions you ask your peers and your supervisor about their insights and experiences. The more you learn, the greater your frame of reference becomes and the better leader you become.

In all cases, be yourself. Whatever makes sense to you should inspire the judgments you make. Whatever you are comfortable communicating or exhibiting in your words and actions should rule the way you communicate ideas, thoughts, and objectives. Your actions and words are being closely examined by your staff because they provide the impetus and inspiration for staff’s activities. Therefore, in the long run, whatever is most natural and comfortable is likely the most progressive precedent to set.

Pace your activities both inside and outside the workplace. Do not try to accomplish everything at once, and make time to enjoy your responsibilities rather than unnecessarily allowing them to be burdensome. Strike a balance between the things that you like to do and the things that you have to do.

Trust your instincts. Your instincts and intelligence are what got you the management job to begin with. As a leader, your good intentions, frame of reference, and basic values are the greatest strengths you have to offer those who want you to succeed. Perhaps the most important point to remember is that the healthcare organization wants you to succeed, your staff wants you to succeed (if for no other reason than it makes their lives easier), and of course you want to succeed. This innate desire, coupled with all the factors discussed throughout this chapter, can allow you to become a strong, positive leader.

Becoming a Transformational Leader

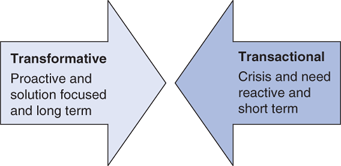

The term transformational leadership is often used to describe someone who uses charisma and related qualities to raise aspirations and shift people and organizational systems into new high-performance patterns. This contrasts with transactional leadership in which a leader adjusts tasks, rewards, and structures to help followers meet their needs while working to accomplish organizational objectives (Figure 6–1).

Transactional leadership meets only part of an organization’s requirements in today’s dynamic environment. A manager must also lead in an inspirational way and with a compelling personality. The transformational leader provides a strong aura of vision and contagious enthusiasm that substantially raises the confidence, aspirations, and commitments of followers. The transformational leader arouses followers to be more highly dedicated, more satisfied with their work, and more willing to put forth extra effort to achieve success in challenging times.

The special qualities that are often characteristic of transformational leaders include

Vision: Having ideas and a clear sense of direction; communicating them to others; developing excitement about accomplishing shared dreams

Charisma: Arousing others’ enthusiasm, faith, loyalty, pride, and trust in themselves through the power of personal reference and appeals to emotion

Symbolism: Identifying leadership heroes, offering special rewards, and holding spontaneous and planned ceremonies to celebrate excellence and high achievement

Empowerment: Helping others develop, removing performance obstacles, sharing responsibilities, and delegating truly challenging work

Intellectual stimulation: Gaining the involvement of others by creating awareness of problems and stirring their imagination to create high-quality solutions

Integrity: Being honest and credible, acting consistently out of personal conviction, and by following through on commitments

Identifying Appropriate Values

As a healthcare manager, you need to determine which values are important for a healthcare department to maintain and enhance. A logical starting point is to examine the larger organization’s values as they are expressed in the mission statement or in other organizational literature.

In general, the following value-based elements should be part of any value-driven healthcare leadership strategy:

Care mandates the provision of health services to patients with the added human touch that all staff members should demonstrate when dealing with each patient.

Concern should be shown by the staff not only to patients, but also to each other. Staff should be concerned about the welfare and development of fellow employees, helping each other through crises, as well as sharing the joy of daily victories.

Compassion is a cornerstone of successful healthcare organizations and must be present at all levels of a facility—including your department.

Two-Factor Theory

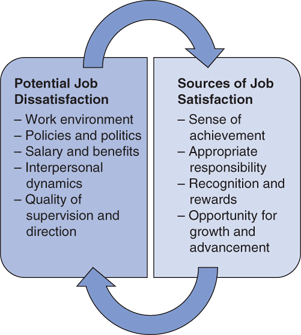

Frederick Herzberg’s two-factor theory offers a now-classic framework for understanding motivation in the workplace. The theory was developed from a pattern identified in the responses of almost 4000 people to questions about work. When questioned about what turned them on, respondents tended to identify things relating to the nature of the job itself. Herzberg calls these satisfier factors. When questioned about what turned them off, they tended to identify things relating more to the work setting. Herzberg calls these hygiene factors defined as sources of job dissatisfaction that are associated with critical aspects of job context. These dissatisfiers are considered more likely to be a part of the work setting than of the nature of the work itself and can include such things as

Working conditions

Interpersonal relations

Organizational policies and administration

Technical quality of supervision

Base wage or salary

Herzberg’s two-factor theory argues that improving the hygiene factors, such as by adding piped-in music or implementing a no-smoking policy can make people less dissatisfied with these aspects of their work. But these changes do not in themselves contribute to increase in satisfaction. To really improve motivation, Herzberg advises managers to give proper attention to the satisfier factors.

As part of job content, the satisfier factors deal with what people actually do in their work. By making improvements in what people are asked to do in their jobs, Herzberg suggests that job satisfaction and performance can be raised. Important satisfier factors include

A sense of achievement

Feelings of recognition

A sense of responsibility

Opportunity for advancement

Feelings of personal growth

Lately, some scholars have criticized Herzberg’s theory as being arcane and difficult to replicate. Yet, as depicted in Figure 6–2, the two-factor theory remains a useful reminder that there are two important aspects of all jobs in health care:

Job content: What people do in terms of job tasks

Job context: The work setting in which they do it

Furthermore, Herzberg’s advice to managers is still timely: (1) Always correct poor context to eliminate actual or potential sources of job dissatisfaction; and (2) be sure to build satisfier factors into job content to maximize opportunities for job satisfaction.

Acquired Needs Theory

David McClelland offers another motivation theory based on individual needs.

Need for achievement is the desire to do something better or more efficiently, to solve problems, or to master complex tasks.

Need for power is the desire to control other people, to influence their behavior, or to be responsible for them.

Need for affiliation is the desire to establish and maintain friendly and warm relations with other people.

According to McClelland, people acquire or develop these needs over time as a result of individual life experiences. In addition, each need carries a distinct set of work preferences. Managers are encouraged to recognize the strength of each need in themselves and in other people. Attempts can then be made to create work environments responsive to them.

People high in the need for achievement, for example, like to put their competencies to work, they take moderate risks in competitive situations, and they are willing to work alone. As a result, the work preferences of high-need achievers include individual responsibility for results, achievable but challenging goals, and feedback on performance.

Exploring Job Design Alternatives

Job design in many ways is an exercise in fit. A good job provides a fit between the needs and capabilities of workers and tasks so that both job performance and satisfaction are high.

To tailor job design to better fit workers’ unique abilities and situations, managers can utilize several common job design alternatives, including job simplification, job enlargement and rotation, and job enrichment.

Job simplification involves streamlining work procedures so that people work in well-defined and highly specialized tasks.

Simplified jobs are narrow in job scope, with a limited number and variety of different tasks a person performs. The logic is straightforward: Because some jobs don’t require complex skills, workers can be easier and quicker to train, less difficult to supervise, and easy to replace if they leave. Furthermore, because tasks are precisely and narrowly defined, workers can become good at doing the same tasks over and over again.

However, there are some downsides to highly simplified jobs. Productivity can suffer as unhappy workers drive up costs through absenteeism and turnover and through poor performance caused by boredom and alienation. The most extreme form of job simplification is automation or the total mechanization of a job.

The process of job simplification dates back to industrial assembly lines, in which each worker did a specific, simple task to help create a complex product, like an automobile. Today, however, job simplification is less common, particularly in complex healthcare workplaces. In fact, while many healthcare jobs are becoming more complex, some entry-level positions (particularly clerical and technical positions within large healthcare organizations) can still be focused and simplified.

One way to move beyond job simplification is to expand job scope by increasing the number and variety of tasks involved in a job.

Job rotation increases task variety by periodically shifting workers between jobs involving different task assignments.

Job rotation in healthcare settings can include clinical, office, and laboratory settings with a series of functional job stations that workers are assigned to and shuffled on an hourly or daily basis.

Job enlargement increases task variety by combining two or more tasks that were previously assigned to separate workers. The process often involves combining tasks done immediately before or after the work performed in the original job.

Frederick Herzberg questions the value of job rotation and job enlargement. “Why,” he asks, “should a worker become motivated when one or more meaningless tasks are added to previously existing ones or when work assignments are rotated among equally meaningless tasks?” By contrast, he says, “If you want people to do a good job, give them a good job to do.”

Job enrichment that builds more opportunities for satisfaction into a job by expanding not just job scope but also job depth—that is, the extent to which task planning and evaluating duties are performed by the individual worker rather than the supervisor.

Dealing with Nonplayers

During the proactive phase of a planned change, managers also need to properly manage nonplayers, those team members who do not agree with the change and even work against it. Typically, nonplayers use an assortment of verbal contentious challenges to derail the change process.

Fortunately, proactive managers can respond to common nonplayer complaints effectively as discussed in previous chapters, for example:

Nonplayer’s ploy: “That will never work!”

Manager’s response: “Well, then tell us specifically what will work.”

Nonplayer’s ploy: “I have got a problem with this.”

Manager’s response: “Redefining problems is useless. Give us a solution that might be useful to achieve our goals.”

Nonplayer’s ploy: “We tried that before, but it did not work.”

Manager’s response: “We are dealing with the present. How can this work now?”

Nonplayer’s ploy: “With all this change, maybe I should find another job.”

Manager’s response: “I will accept your resignation immediately because change will be constant for years to come in health care.”

As these responses indicate, managers can use three principles in managing the nonplayer’s resistance.

Issue a direct, tactful challenge to the complaining nonplayer. Do not allow the nonplayer to complain or cast dispersions on group plans without contributing a better idea. The only individual more detrimental to a healthcare organization than a nonplayer in this regard is a manager who allows negativity to become acceptable behavior without holding the nonplayer accountable for constructive contribution, not just destructive criticism.

Use plural pronouns, such as we and us. Doing so encourages the group to recognize that the nonplayer is questioning the entire group’s capability, not just yours. This encourages other team members to become accountable for group direction and goal formation, and enlists their participation in countering ill-conceived negativity.

Use bottom-line vernacular. Use words such as useless and immediately, so that the nonplayers are clear in their understanding that game playing, dissention, and group denigration are intolerable when striving for group achievement.

A final component of the proactive stage is your display of natural emotions. Don’t be a Pollyanna or Jack Armstrong with an unwarranted positive outlook in the change process; show honest emotion. The group usually recognizes that a manager is in the same boat as they are and will continue to row accordingly.

Understanding Why People Resist Change

Numerous reasons exist for why people in organizations resist planned change. Some of the more common include

Disrupted habits: Feeling upset when old ways of doing things can’t be followed

Loss of confidence: Feeling incapable of performing well under the new ways of doing things

Loss of control: Feeling that things are being done to you rather than by or with you

Poor timing: Feeling overwhelmed by the situation or that things are moving too fast

Work overload: Not having the physical or psychic energy to commit to the change

In addition to the preceding, fear is probably the most prevalent emotion cited by healthcare leaders as a major factor in the change process. Nearly everyone experiences uncertainty—fear of the unknown—when they don’t understand what is happening or what is coming next.

Another prominent fear for steady players—who often represent the silent majority of a team—is fear of regression. Steady players often view any change with apprehension if the proposed change is not completely presented in a fashion that highlights its improvement value to the status quo. Managers can address fear of regression proactively by recognizing that most steady staff members eventually accept change, provided it is not simply change for the sake of change. As a leader, you have a responsibility to identify how the proposed change brings about new benefits for patients, your organization, your team, and individual team member.

Low-performing staff members—both nonplayers and new, less experienced, and confident employees—often fear having to do more work. Change usually requires increased effort and higher contribution from all staff members. For low-performing staff, increased performance demands are ultimately threatening, because their current level of nonperformance and resistant behavior will be exacerbated by more pressure for optimum performance and an accelerated pace of action. Put bluntly, the need for change presents a great opportunity for low-performing staff to be exposed as incompetent, noncontributory, and detrimental to the provision of stellar health care.

If job descriptions and other substantiating criteria are in place for assessing performance, the change dynamic can provide an excellent opportunity to appraise the low-performing employee’s contributions and provide the impetus for termination. This strategy is rightsizing the right way, because successful healthcare organizations can only afford to employ individuals who are motivated, competent, and aware that the organization is more important in the work scheme than individual preferences, dissenting opinion, and other me first mentalities.

The Power of Thank You

Perhaps the two most underutilized words at any level of healthcare leadership are Thank You. However, these words can realistically and resonantly provide motivation to staff members at any level in a timely and positive manner. If used too often and overemployed, the power of thank you can be compromised by being perceived as redundant and would be diluted from overuse. An example would be profusely thanking an employee for doing something which is part of their normal job responsibilities, as opposed to using it for when the employee truly goes above and beyond the call of duty.

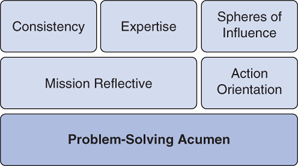

There are several nuances to using thank you which will also underscore important themes in a healthcare workplace, as seen in our illustration and outlined below.

Consistency: To establish consistency of action as an essential workplace value, the phrase as always should be linked to the appreciation shown to an employee. For example, if a nurse has gone the extra step to ensure that a child was not fearful of receiving a tetanus shot while ensuring that the patient flow in the entire office kept moving, the physician leader can say, “Debbie—great job as always; with your quick and thoughtful action, you made sure that a little kid was not scared and allowed us to take care of all of our patients.” It is particularly important in the case of new employees that significant action in this semblance is explained in a manner that helps them understand not only the expectation held in a job position but why a particular action and the workplace value that is underscored are vital to the success of the entire operation.

Expertise: Unique in healthcare workplace is the fact that all staff members have a particular acumen in their field. A skillful leader can adroitly call upon the expertise of each staff member to achieve the desired result. Hence, it is important to underscore the appreciation that the physician leader holds for his/her staff members’ expertise by citing it specifically as part of their conveyance of thanks. For example, if a radiology technician has been a particularly stellar analysis of a scan, the physician leader can say, “Thanks much—when we have a complicated case like this, we always look to you as the expert to make sure we get ‘the right picture.’”

Excellence: Outstanding achievement on the part of the staff member should be recognized forthrightly and directly when it occurs. Along with an appropriate citation in the leader’s notebook, the healthcare executive should make sure to say thank you on the spot, so that the exemplary action is captured is highlighted exactly as that—something which is a great example that should be celebrated and exhibited in full view of the entire staff if possible. Keeping with the leadership principle of always commending outstanding action, the physician leader should employ words such as outstanding, excellent, and remarkable to highlight significant action and critical contributions among their charges.

Problem-solving acumen: A most valuable commodity at any healthcare team as the ability to quickly and effectively solve vexing problems in the caregiving process as well as across the span of the operational sphere of the work unit. Accordingly, when a staff member comes up with a practical solution to a problem, particularly one which is confounding the entire team, it is the responsibility of the physician and healthcare leader to not only thank the positive catalyst staff member but also specifically cite as noteworthy the ability to solve problems. This naturally and fluidly reminds all members of the staff that problem solving based on innovative use of available resources in an efficient and effective manner is rewarded in the workplace and encouraged as a daily responsibility for all members of the team.

Action orientation: The requisite of taking swift and pertinent action, especially during a crisis (which is at least a once a day event in most healthcare settings) is the characteristic which also should be encouraged through the power of thank you on the part of a physician leader. Outstanding action when confronted by change, conflict, challenge, or crisis based on strong decision making, fortitude, and professional ability is a gold standard in any healthcare team. Healthcare professionals at every level must be certain that when they are charged with taking vital independent action in critical situations, they will be encouraged, supported, and appreciated by their leadership. Thus it becomes particularly important that this is part of the appreciation calculus on the part of the physician leader. The physician leader should cite both the crisis at hand as well as the strategy employed by the superstar who took significant action to save the day for the whole team. As is the case with all the strategies in this section, the thanking can be conveyed verbally as well as in written or e-mail fashion; with this particular characteristic, it might be notably worthwhile to send the action-oriented hero an e-mail thanking them for their action with a cc to your boss as well as a copy for their personnel file in human resources to ensure that the action as noted is part of their work record.

Mission reflective: All healthcare organizations have a legacy and a lineage within a community which is likely honored by all members of the community as reflected in their continued patronage and support of the healthcare organization or medical practice. A vivid example of this factor would be found in Clara Maass Medical Center in New Jersey which is named after a true healthcare heroine who is a nursing pioneer who literally sacrificed her life in the interest of developing a vaccine for yellow fever. In this case, it is relatively easy for a healthcare leader working at Clara Maass Medical Center to cite a particular action as being reflective of the time-honored mission personified by the self-sacrifice and devotion to duty of their organization’s namesake. All healthcare organizations and medical practices have a mission which is usually well publicized and clearly stated to each and every staff member, to include usually a set of values and perhaps in an organizational credo, or a set of beliefs. When thanking a staff member for extraordinary action which is specifically reflective of the organization’s mission, the physician leader should try to specify which one of the values the action reflects when expressing appreciation for the action. For example, the leader can say, “I know it took a lot of time for you to take care of that elderly gentleman who we discharged last week. Not only is patience a virtue, but compassion and commitment to our community members is a major value of our organization; without question, your actions last week in taking care of that gentleman reflected the true compassion and real commitment that we aspire to provide an organization.”

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree