Modified Radical Mastectomy

Tiffany A. Torstenson

Judy C. Boughey

DEFINITION

Modified radical mastectomy (MRM) is a surgical procedure that removes all breast tissue and lymphatic-bearing tissue in the axilla. This operation removes the nipple-areolar complex, skin envelope, and level I and II axillary nodes but spares the pectoralis major muscle. It can also be termed as a total mastectomy with an axillary lymph node dissection.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

There has been a huge evolution in types of the mastectomy over the years. We have moved away from the radical mastectomy to more cosmetic pleasing procedures such as simple mastectomy, skin-sparing mastectomy, and nipplesparing mastectomy. In mastectomy patients with nodepositive disease, axillary lymph node dissection is often recommended.

Patients undergoing an MRM usually have documented lymph node metastases diagnosed preoperatively or surgically and either elect to have a mastectomy or require a mastectomy (i.e., are not candidates for breast-conserving therapy). Patients diagnosed with inflammatory breast cancer should also undergo an MRM after induction chemotherapy according to National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines.1

It is crucial to decide from the beginning if these patients are operable candidates and whether neoadjuvant therapy should be considered. A multidisciplinary approach is vital in the treatment success of these patients. Involvement of a medical oncologist and radiation oncologist early in the management of these patients helps treatment planning and to streamline patient care.

A comprehensive history and physical examination is imperative on the first consultation with these patients. The history should be very detailed and include questions pertaining to medical conditions, medications, surgeries, allergies, and also about any musculoskeletal issues, which could affect operative positioning. It is important to evaluate for any family history of breast or ovarian cancer.

If there is a strong family history of breast or ovarian cancer, it is essential to offer genetic counseling and possibility of genetic testing.

Physical examination starts with an inspection of bilateral breasts both with arms at the patient’s side and with the arms elevated, noting any asymmetry, nipple retraction, prior scars, or skin changes.

Palpation of the breasts should always be done both in a sitting and supine position in a circular or vertical pattern. Palpable masses should have bidimensional measurements and should be assessed for chest wall adherence and skin proximity. Any palpable masses that do not correspond to radiologic findings require further testing and tissue biopsy.

A thorough examination of the lymph node basins should be performed, including the axillary, cervical, supraclavicular, and infraclavicular nodes. If there is adenopathy on palpation, patients should undergo an in-office or radiologic ultrasound. Any suspicious nodes on imaging should undergo a fine needle aspiration or core needle biopsy.

Imaging and pathologic diagnoses should be shared and explained to the patient. It is helpful to map out the incisions for the patients to see preoperatively. Explain to patients the need for either neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy as well as likely need for postmastectomy radiation in patients with node-positive disease.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy has been shown to be equivalent to adjuvant chemotherapy in terms of survival and can increase rates of breast-conserving therapy.

Postmastectomy radiation in node-positive disease decreases rates of locoregional recurrence and increases disease-free and breast cancer-specific survival.

Inquire if patients are seeking immediate reconstruction or desire to go flat chested. If postmastectomy radiation is recommended, patients may not be candidates for immediate reconstruction.

Allocate enough time to spend with these patients in order to answer all their questions, and be empathetic to their needs during this emotional time. Keep interruptions with pagers and cell phones to a minimum.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Breast imaging plays a vital role in the screening and diagnostic workup for breast cancer. Imaging can define the extent of the disease and help assess for any abnormalities in the contralateral breast. It is also used as a monitor for local recurrence in patients postoperatively.

Mammography is the initial imaging test in the breast cancer workup. Mammograms are very sensitive in detecting abnormalities and have been shown to decrease breast cancer mortality approximately by 30%. Screening mammograms should begin yearly in women who are 40 years of age and asymptomatic.2

Diagnostic mammograms should be obtained in any patient being considered for an MRM (FIG 1). Spot and magnification views can help aid to focus and distinguish abnormalities. Implant displacement views (Eklund views) should be obtained in women with implants.2,3 Request films if they were done at an outside institution. An ultrasound should also be performed to further assess the size of the tumor and the proximity of it to the skin and chest wall. Lesions that are suspicious on ultrasound or mammogram should undergo a percutaneous biopsy.

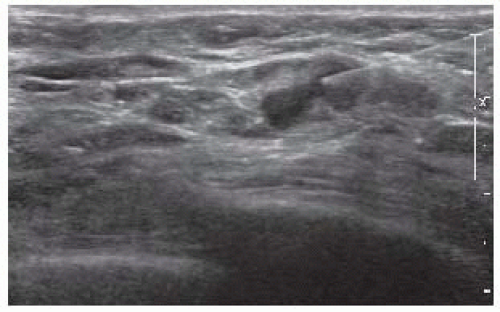

Axillary ultrasound should be performed in patients with a biopsy-proven invasive cancer. Lymph nodes should be evaluated for their size, shape, and morphology. Suspicious nodes

on imaging or clinically palpable nodes should undergo a fine needle aspiration or core needle biopsy with ultrasound guidance (FIG 2). Approximately 31% of axillary metastases are diagnosed with ultrasound-guided biopsy.

FIG 1 • Mammogram showing a right invasive ductal carcinoma invading the skin and causing skin retraction.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) usage is still controversial but can be used as an additional imaging tool for screening, staging of known breast cancers, and evaluating the contralateral breast. MRIs are highly sensitive tests but lack specificity leading to an increased false-positive rate. Studies have also demonstrated an increased rate of mastectomies in patients undergoing MRIs. The decision to order an MRI should be based on the recommended indications and individualized.

According to NCCN guidelines, positron emission tomography (PET) scans can be used to evaluate for distant metastasis in patients with stage IIIA breast cancer, but this is a category 2B recommendation. Systemic staging is not recommended for patients with early stage breast cancer in the absence of symptoms.1

When a suspicious lesion is identified on imaging, a tissue biopsy is needed to decipher between a benign and malignant process. Percutaneous biopsy is preferred over an excisional biopsy, which can lead to unnecessary surgeries for benign entities. Core needle biopsy is preferred to evaluate histology and differentiate in situ from invasive disease. Most lesions in the breast will need to undergo a core needle biopsy using ultrasound or stereotactic guidance. MRI-guided core needle biopsy can also be performed when lesions are not detected on ultrasound or mammography but these are more technically challenging. If cancer is identified, there should be a detailed pathologic assessment, including subtype and hormone receptor status. In cases with morphologically abnormal lymph nodes on ultrasound, fine needle aspiration biopsy or core biopsy of lymph nodes should be used.

FIG 2 • Ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration of an axillary lymph node that revealed metastatic carcinoma in a male breast cancer patient who underwent an MRM.

After any percutaneous biopsy, a marking clip should always be placed. This is extremely important in patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

Preoperatively, patients can be considered for regional anesthesia at the surgeon’s and anesthesiologist’s discretion. Paravertebral blocks (PVBs) are increasing in popularity for breast surgery and are more commonly favored over epidural blocks. They can be performed as single- or multiple-level injections or as a continuous catheter infusion. PVBs have been shown to shorten recovery times and length of hospital stays, decrease opiate usage, and decrease the incidence of vomiting. It is also hypothesized this type of regional anesthesia may protect the immune system and decrease metastasis.4

PVBs are preferred over epidural blocks because they induce less hypotension, less urinary retention, are technically easy to learn, and have less severe side effects. Patients who are coagulopathic or who have musculoskeletal deformities such as kyphosis or scoliosis should not be considered for a PVB.5,6

Potential complications associated with a PVB are pneumothorax, vascular penetrance, sepsis, and hematoma. Pneumothoraces are more common with multiple-level injections in comparison to single-level injections. Patients can either be seated with the spine in a kyphotic curve or placed in a lateral decubitus position (FIG 3). The local anesthetic is injected in the paravertebral space where the thoracic spinal nerves emerge.

Ultrasound can also help guide the correct placement of the local anesthetic. Patient comfort improves when an ultrasound is used, and the pneumothorax rate decreases due to the direct visualization of the pleura.

Before patients enter the operating theater, they should be site marked in the preoperative area to ensure the correct side is being operated on. Radiologic imaging should be thoroughly reviewed prior to the procedure to ensure the location of the tumor and the proximity of it to the skin.

Prophylactic antibiotics have been shown to reduce postoperative infections and should be administered prior to incision.7 Most surgeons prefer to avoid the use of paralytics during an MRM in order to aid identification of important motor nerves, but excessive handling of these nerves is discouraged to prevent axonal injury.

Prophylactic anticoagulants for prevention of venous thromboembolism (VTE), such as subcutaneous heparin, should be considered on a case-by-case basis. Sequential compression devices should be placed prior to initiation of general anesthesia for VTE prevention.

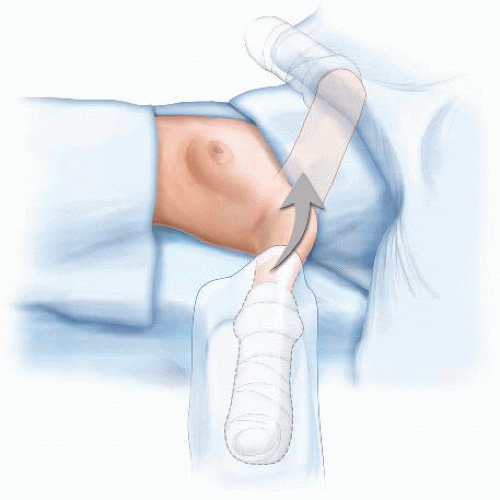

Positioning

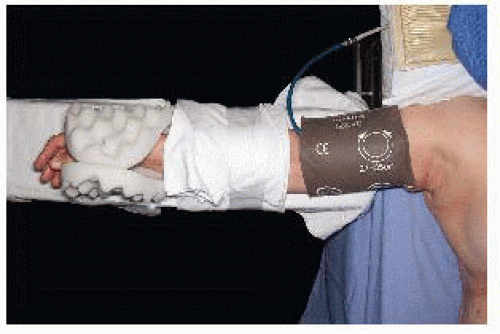

Correct positioning of patients undergoing an MRM is vitally important. Patients should be in a supine position with the side of the MRM close to the edge of the operating table. The endotracheal tube should be positioned toward the contralateral side of the mouth from the side of the MRM. Arms should not be abducted greater than 90 degrees to prevent injury to the brachial plexus. Arms should be placed on padded arm boards and positioned in a way that pressure points are alleviated. It is often helpful, particularly with bulky adenopathy, to prepare the ipsilateral arm into the field and wrap it with a sterile stockinette and Kerlix wrap (FIG 4). This allows for relaxation of the pectoralis muscles and easier access to the level II and III axillary nodes.

The arm should be secured to the arm board. Blood pressure cuffs and intravenous (IV) lines should be placed in the contralateral upper extremity (FIG 5). Allow enough room between the operating table and anesthesiologist cart to allow an assistant to stand above the arm.

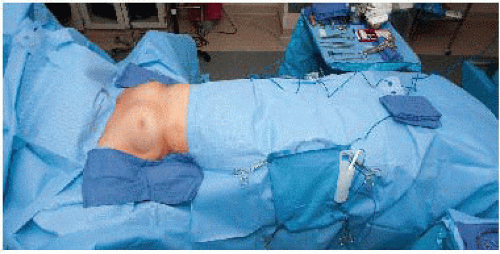

Surgical preparation should include the breast and axilla and extend across the midline, inferiorly onto the abdomen, superiorly to the neck and the upper arm, and laterally to the level of the operating table. Draping should ensure preservation of a sterile field with exposure of the whole breast and axilla (FIG 6).

FIG 6 • Draping should ensure preservation of a sterile field with exposure of the whole breast and axilla. |

TECHNIQUES

INCISION PLACEMENT

There are many options for incisions for a total mastectomy that are based on the tumor location. In an MRM, it is important to have an incision that provides good exposure to the axilla and reduces skin redundancy. The incision should include the skin overlying the tumor in cases where the tumor is close to the skin and a 1- to 2-cm margin around the tumor and include the previous biopsy site.

The classic Stewart incision is a transverse elliptical incision, provides access to the axilla, and is the preferred incision of many plastic surgeons for patients seeking delayed reconstruction (FIG 7).

When mapping the incision, it is important to make sure there will be adequate skin for a tension-free closure without excess skin for redundancy (FIG 8A,B). Most of these patients will be receiving postmastectomy radiation, which can lead to incision breakdown, and this is increased when incisions are under tension. The boundaries of the breast (clavicle superiorly, inframammary fold inferiorly, sternum medially, and midaxillary line laterally) define the extent of the flap dissection.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree